Abstract

Treatment of petroleum spills and organic solvent pollution in general is an important issue; several techniques are under development to remove oil from water. The use of absorbents is one of the most common techniques to tackle this problem. These absorbents can be classified based on their characteristics of recyclability into irreversible and reversible ones. In this review, we discuss the application of several materials as oil absorbents, according to their classification and characteristics such as hydrophobicity, surface area and oil absorption capacity. Also, the fabrication methods for some materials are presented and analyzed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Treatment of oil spills is an important issue for environmental science and technology. In the last decades, the environmental pollution caused by oil spills on rivers and oceans has been a great concern (Fingas 2012). Several techniques have been developed for oil removal from water; among them are the uses of chemical dispersants and sorbents, bioremediation, skimmers, burning, etc. (Ge et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2015a; Teisala et al. 2014). Highly efficient absorbents are mainly used in these processes (Ceylan and Dogu 2009; Radetic et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2015b). High capacity of absorbents for oil absorption is commonly correlated with the porosity of the materials (Adebajo et al. 2003; Rengasamy et al. 2011); for this reason, highly porous materials are regularly used as oil absorbents. Syntheses of materials with specific pore diameters (mesoporous and macroporous) for their use as oil absorbents have been offered (Lei et al. 2013; Li et al. 2013).

Hydrophobicity is one of the most important properties of oil absorbents. Highly hydrophobic absorbents (Feng et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2015b) exhibit a better efficiency for oil absorption than low-hydrophobic absorbents. The cost of the absorbents might be low due to the large amounts required for cleaning oil spills. Besides, the development of absorbents capable of being recycled would be an interesting achievement in oil spills treatment. Absorbents with highly porous structures and superhydrophobicity would be capable of very efficient removal of oil spills. For this purpose, efforts are needed to find eco-friendly materials with superhydrophobicity properties, making them selective for the absorption of oil as well as enhancing their buoyancy, recyclability and price (Korhonen et al. 2011).

2 A brief summary on the materials absorbing organic phase irreversibly

The most common method for irreversible removal of oil from water is the use of hydrophobic absorbents. Earlier (Adebajo et al. 2003; Al-Haddad et al. 2007; Carmody et al. 2007) and recent (Ge et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2015a) works on absorbents indicated the importance of the employment of these materials. One of these methods is based on carbon-containing nanomaterials. Thus, syntheses of carbon nanotubes and nanofibers on expanded vermiculite (EV) surface were carried out by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (Moura and Lago 2009). The growth of carbon nanotubes and nanofibers was catalyzed by nanoparticles of Fe and Mo, producing a resulting sponge structure. The final product showed high hydrophobicity and buoyancy making it a potential oil absorbent, showing an increase of 600% of its absorption capacity compared with the initial material. Also, enhancing the hydrophobicity of this material, the amount of absorbed water per gram of absorbent decreases dramatically (from 3.5 g of water to 0.5 g). This type of synthesis was demonstrated to be very successful in avoiding any damage to the porous structure of the EV. CVD is a relatively low-cost method that can be used in large-scale production of this type of absorbent. In a related report (Angelova et al. 2010), a carbon/SiO2 composite was prepared from rice husks as precursor using the pyrolysis technique (450 °C/3 h). The obtained product contained 98% SiO2. The absorption tests showed its higher oil absorption capacity (2–3.5 times) compared with the material before performing pyrolysis, showing its potential use for water clean-up from oil spills.

Silica-based nanocomposites are known not only for this composite above with carbon nanotubes (CNTs), but also in combination with polymers. For example, materials capable of gelling oil in oil spills were similarly synthesized by CVD resulting in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) on silica nanoparticles (Cho et al. 2014). These PDMS-coated silica nanoparticles showed high hydrophobicity, stability, and oil gelation selectivity, being able to gelate 15 times the capacity of the uncoated silica nanoparticles. These features make it a gelating agent for different types of oils. On the other hand, the use of absorbents based on natural products has been growing in recent years. Absorption studies of oil, water, and buoyancy were performed testing these features in natural absorbents (Rotar et al. 2015). Absorbents such as Nature Sorb (mixture of sphagnum peat moss, charcoal, and sawdust) and Sphagnum Dill (Russian peat moss) demonstrated high absorption capacity and a long period of buoyancy compared with sawdust. The use of this kind of natural absorbent for removing oil in water can achieve levels of 0.03 g of oil per liter of water. As the material is environmentally friendly, its use as potential oil absorbent is interesting. Heat treatment (150–250 °C) was performed on sawdust to increase specific absorption of high viscosity oil derivatives. Although a practical and easy extraction of the absorbed material is not possible, the oil absorbents can be used as fuel by burning them directly after oil absorption.

3 Materials capable for multiple reversible absorption/desorption processes

3.1 Zeolites

Previous works (Carmody et al. 2007; Alayande et al. 2016) focused on the synthesis of hydrophobic zeolites as an alternative for activated carbon absorbents. Natural zeolites are aluminosilicate minerals with a 3-D structure. Their wide pores and large surface area make possible the removal of impurities from water and air (Al-Haddad et al. 2007). The absorption of petroleum hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and sulfur or ammonia compounds has been studied using zeolites (natural and synthetic) as absorbents. Natural and manufactured zeolites have been tested in wastewater where zeolites performed a better absorption process of several ammonia compounds (84.4% of removal) than activated carbons (15.6% of removal). The selective absorption of metals and ammonia makes zeolite a potential absorbent for wastewater treatment, but not for refinery wastewater due to high content of oil derivatives.

In a related report (Carmody et al. 2007), Wyoming Na-montmorillonite, octadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (ODTMA), dodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDDMA), and di(hydrogenated tallow) dimethylammonium chloride (commercial name Arquad 2HT-75) were used to synthesize organo-clays which might present hydrophobic or organophilic surface depending on the exchanging ions. The absorption capacity of the synthetized organo-clays was tested using three types of oil (diesel, hydraulic oil, and engine oil). It was observed that with increasing content of long chain hydrocarbon, the absorption capacity of the organo-clay was found to be higher. Organo-clay with certain hydrophobicity, absorption and retention capacities might be synthesized through the control of variables and their combinations. However, organo-clays exhibit some disadvantages including high cost, low biodegradability and low recyclability.

On the other hand, the synthesis of functionalized nanosorbents with residues from the distillation of oil (vacuum residue) and alumina nanoparticles have a great potential due to their low cost and high hydrophobicity (Franco et al. 2014). The materials were tested under different conditions where high absorption capacity and retention of oil can be achieved at neutral pH and a 4% load of vacuum residue. The synthesis of this material has the economic advantage of the use of an industrial residue as precursor; however, its use requires specific conditions to obtain the maximum absorption capacity restricting the adaptability. In a similar report (Alayande et al. 2016), an expanded polystyrene (EPS) and zeolite were used to synthetize beaded fibers with a zeolite matrix by electrospinning, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The material presents superhydrophobic properties (Fig. 3) and high absorption capacity of oil due to the zeolite porous matrix.

Surface morphology of 20% EPS electrospun at A1 11.5 kV, 20% PS; A2 15 kV, 20% PS; B1 20% PS/zeolite at ×500; B2 ×50,000. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Alayande et al. 2016)

Surface morphology of C1 EPS/zeolite film; C2 EPS film. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Alayande et al. 2016)

Water contact angle of a 20% PS/zeolite and b 20% PS. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Alayande et al. 2016)

Concluding this section, such properties of zeolites as high porosity and large surface area are key features in the processes of oil removal from water. However, other properties as hydrophobicity, absorption capacity, and retention of oil are also important in order to achieve a complete cleaning of impurities in wastewater, seawater or other aquatic systems.

3.2 Aerogels

The term “aerogel” is a gel material, in which its liquid component has been replaced with gas to leave an intact solid micro- or nanostructure without pore collapse; aerogels contain ~99% air by volume (Zuo et al. 2015). Different types of aerogels are known, for instance silica-based aerogel (Rao et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2010, 2012; Olalekan et al. 2014), cellulose-based aerogels (Korhonen et al. 2011), clay-based aerogels (Rotaru et al. 2014), carbon-based aerogels (Kabiri et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2015a; Zeng et al. 2009; Zuo et al. 2015), etc. The methods of synthesis for each type of aerogel vary depending on the final application; however, supercritical drying or freeze-drying is fundamental in order to obtain final aerogels.

The synthesis of silica-based aerogels is carried out by well-known methods for advanced nanoporous materials; however, their applications require deeper studies. Due to their own properties such as high surface area, hydrophobicity and porosity, a study of the sorption of three oils (vegetable oil, motor oil, and crude oil) was carried out (Wang et al. 2012). Using Cabot nanogels (silica-based aerogels) with different particle sizes, a high capacity for adsorption of oils was observed. Their capacity of absorption depends on the stability of the mixture of water and oil. In the cases where the emulsion was stable, the absorption capacity of the aerogel decreased tenfold. In order to avoid this issue, the use of sustainable materials such as plants and some soils as aerogel precursors was offered. These materials exhibit the advantages of being renewable, natural and with low impact on environments due to their high compatibility with nature. For example, the functionalized cellulose aerogel with hydrophobic coating (TiO2) and a process of freeze-drying produce nanocellulose aerogels (Korhonen et al. 2011). Aerogel structure is created by the connected fibers of the nanocellulose, and Fig. 4 illustrates their resulting morphology with and without the coating. The composite exhibited absorption capacity of 20–40 (wt of oil/wt of absorbent) but also, it can be reused (10 times) since the absorption capacity does not change. After the oil absorption, it requires only a wash with solvent in order to be reused as sorbent or can be incinerated in order to use it as a fuel.

Microscopic structure of the native nanocellulose aerogels. SEM micrographs of a freeze-dried nanocellulose aerogels, and b a magnification of a sheet. c TEM micrograph of a nanocellulose fibril with a uniform 7 nm TiO2 coating. Reproduced with permission of ACS from (Korhonen et al. 2011)

Also, the use of carbon-based aerogels is more frequent now; in particular, “greener synthesis” has nowadays attracted attention. The development of these nanomaterials which do not only accomplish the final application but also their synthesis using low-toxicity chemicals and reducing the number of steps of the process are important. The synthesis of graphene–carbon nanotube aerogel has been reported by greener techniques, where the interaction of the graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes was performed in a one-step process (Kabiri et al. 2014). A schematic diagram of the synthesis procedure is represented in Fig. 5. Carbon nanotubes provide the hydrophobic and porous property to the product (Fig. 6), promoting the absorption of oil products. The synthesis method used is economically attractive and simple for scalable production. A possible absorption process to implement on a large scale is shown in Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram for synthesis of the graphene–CNT aerogels: a GO sheets, b CNT bundles, c the mixture of GO and CNT prepared for d the graphene–CNT hydrogel, and e the formation of graphene–CNT aerogel by freeze-drying from hydrogel. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Kabiri et al. 2014)

Digital photographs showing the adsorption of vegetable oil on a water surface using prepared graphene–CNT aerogels at different times: a t = 0 s, b t = 10 s, and c t = 20 s. d Adsorption capacity graph of graphene–CNT for oils and several organics using pure oil and solvent and their mixtures with water. e The relationship of adsorption capacity with density of oil and organic solvents without water in the system. The inset shows the contact angle (CA) measurements of graphene (GN), CNT, and graphene–CNT aerogel (GN–CNT), respectively. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Kabiri et al. 2014)

Digital photographs showing a the packed plastic tube of graphene–CNT aerogels and b–e the progress of the continuous adsorption and removal of gasoline from a non-turbulent water–oil system. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Kabiri et al. 2014)

Clay-based aerogels combine the hydrophobicity of organo-clays with the large porosity of the aerogels making them an interesting candidate for oil spill clean-up. Various amounts of montmorillonite (MMT), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) were tested to synthesize clay-based aerogels (Fig. 8) (Rotaru et al. 2014). The absorption capacity determined under the optimal conditions was 23.6 g g−1 for dodecane and 25.8 g g−1 for motor oil. The process of absorption of dodecane on water with the synthetized aerogel is shown in Fig. 9. The percentage of recovery of the absorbed oil was estimated by free drainage (from 1.06% to 14.9%) followed by centrifugation of the absorbent (from 42.3% to 66.0%). This study reveals the high absorption capacity, hydrophobicity (116°), and the possible recycling of the aerogel under the optimal conditions of synthesis.

Pillow-type sorbent (P-M17) consisting of clay polymer aerogel (M-17) surrounded by hydrophobic polypropylene (PP) nonwoven fabric as containment barrier. a Top view. b Cross-sectional view. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Rotaru et al. 2014)

Pictures showing the application of the pillow-type sorbent (P-M17) for oil spill clean-up. a Sudan IV dyed dodecane spilled onto water surface (oil slick layer of 2.5 mm). b Addition of P-M17 pillow sorbent and dodecane sorption after 10 s contact time. c Dodecane sorption after 15 min contact time. d After separation. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Rotaru et al. 2014)

3.3 Polymers

The polymeric absorbents such as polyurethane, polypropylene, polyethylene, and cross-linked polymers are the most commonly absorbent for oil spills. Due to their high porosity, absorbent capacity and hydrophobicity, these polymers have been widely used for the absorption of organic compounds. Thus, innovations in this area have become imperative. The creation of novel polymeric systems like polymer-based absorbent (Keshavarz et al. 2015; Li et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2015b; Nikkhah et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2015), polymer absorbents (Kundu and Mishra 2013; Lin et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2013) and polymeric coatings (Chen et al. 2013; Machado et al. 2006) of different materials are reported. Thus, a common and suitable process was creating an absorbent on the basis of carbon nanotubes and polyurethane (Wang et al. 2015). This absorbent presented superhydrophobicity and a high absorption capacity (34.9 times its own weight). The synthesis method consists of the oxidative self-polymerization of dopamine followed by a reaction with octadecylamine. The mechanical strength of the absorbent was improved by the deposition of carbon nanotubes on the sponge skeleton. The recyclability of the as-prepared absorbent was 150 times without losing its high absorption capacity.

Also, the uses of polymer-coated materials are very common, in particular those having magnetic properties. Thus, the two-step synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4) coated with polystyrene was carried out and the products were tested as oil absorbents (Chen et al. 2013). The hollow Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the polystyrene-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles are shown in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively; the use of this polymer on the magnetic nanoparticles generates a hydrophobic property that enhances the oil absorption of the composite. The magnetic properties of the coated nanoparticles were used to remove oil from water using a magnet (Fig. 12). Due to its hydrophobicity, this nanocomposite presented a selective absorption exclusively for the oil. The absorption capacity of its coated nanoparticles was shown to be 3 times its own weight. Furthermore, the oil could be removed from the nanocomposite implementing a simple treatment and does not affect its future performances.

TEM images (a, b) and SEM images (c, d) of hollow Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Chen et al. 2013)

TEM images (a, b) and SEM images (c, d) of Fe3O4@PS nanocomposites. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Chen et al. 2013)

Photographs of the removal of lubricating oil from a water surface by Fe3O4@PS nanocomposites under the magnetic field. The lubricating oil was labeled by Sudan I dye for clarity. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Chen et al. 2013)

An easy polymerization of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) was achieved using sugar to make a porous material that can absorb larger oil quantities at less time (Zhang et al. 2013). This synthesis involves PDMS, p-xylene, and sugar (coarsely granulated sugar, CGS; finely granulated sugar, FGS; soft sugar, SS). A porous skeleton was created (Fig. 13), and the absorption capacity, hydrophobicity, and recyclability of the processes were evaluated. The absorbent presented an absorption capacity in the range of 4–34 g g−1 depending the oil and organic solvent. The recycling process showed a recyclability of 20 times losing only a little of its original absorption capacity. Furthermore, this synthesis method could be used to design novel polymeric absorbents.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of sugar particles and PDMS oil absorbents. a–c CGS, FGS, and SS, respectively. d–h PDMS oil absorbents prepared by CGS, FGS, SS, a mixture of CGS and SS, and a mixture of FGS and SS, respectively. Reproduced with permission of ACS from (Zhang et al. 2013)

3.4 Natural and natural-based products

The study of hydrophobic properties, absorption capacity, and buoyancy in absorbents has been increased over time since these properties are key features in the treatment of oil spills. Most common absorbent materials are based on polymers, which are oil-based. The aim of these innovations is to produce absorbents based on cheap and commercially available natural products. This area can be divided into two large groups, natural absorbents (Abdelwahab 2014; Behnood et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2013; Ifelebuegu et al. 2015; Machado et al. 2006; Muhammad et al. 2012; Rotar et al. 2014; Ribeiro et al. 2003; Sayyad Amin et al. 2015; Wahi et al. 2013; Zadaka-Amir et al. 2013) and natural-based absorbent products (Fu and Chung 2011; Galblaub et al. 2016; Raj and Joy 2015; Kudaybergenov and Ongarbayev 2012; Nwadiogbu et al. 2016; Okiel et al. 2011; Uzunov et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013; Zang et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2011). Natural absorbents are those that can be obtained in nature and are used without modifying their hydrophobicity properties, absorption capacity, buoyancy, etc. These materials are commonly used after a drying process to eliminate the water adsorbed on the structure of the material. Some selected works reporting the use of natural absorbents are listed in Table 1.

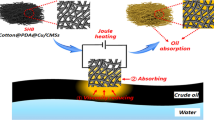

The natural-based absorbents are natural absorbents with a modified surface using different types of materials or by a change on the chemical composition of their surface to achieve a better hydrophobicity and, oil absorption capacity. The modification of these materials can be carried out by methods such as CVD, dip-coating, pyrolysis, etc. In Table 2 are presented several reports in this field (Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25).

Images showing the morphology of a the EV and b the as-obtained EV/CNT hybrids after a 120-min reaction; SEM images showing the morphology of c the EV and the EV/CNT hybrids with a CNT content of d 11.4% in EV/CNT-5 for a 5-min reaction, e 33.1% in EV/CNT-30 for a 30-min reaction, f 67.6% in EV/CNT-60 for a 60-min reaction, g 91.0% in EV/CNT-90 for a 90-min reaction and h 94.8% in EV/CNT-120 for a 120-min reaction; i TEM and inserted high-resolution TEM images showing the tubular structure of the CNT in the EV/CNT hybrids. The EV layers in d–h are indicated by white arrows, while the aligned CNT arrays in d–h are indicated by black arrows. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Zhao et al. 2011)

Cross-sectional FE-SEM images of cotton fibers and CCFs with hollow structures. a, b CCFs-400. c CCFs-600. d CCFs-800. e CCFs-1000. f Cotton fibers. Reproduced with permission of ACS from (Wang et al. 2013)

Floating-ability test of CCFs-400 after crude oil sorption. a Crude oil on the water surface. b CCFs-400 sorbents placed on the spill area. c CCFs-400 starting to adsorb oil. d Crude oil adsorbed by CCFs-400. e CCFs-400 floating on the surface after crude oil sorption. f Cleaned water surface. Reproduced with permission of ACS from (Wang et al. 2013)

Photographs of a behavior of a water droplet on pristine sawdust, b behavior of a water droplet, and c oil droplet on as-prepared superhydrophobic/superoleophilic sawdust. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Zang et al. 2015)

The process of resulting sawdust product as an oil sorbent for the separation of water and gasoil mixture. a As-prepared superhydrophobic/superoleophilic sawdust. b Water and gasoil mixture (gasoil was colored with Sudan III for clear observation). c All given red gasoil was absorbed and red sawdust floated on the water. d After adsorption, the sawdust filled with red liquid was separated. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Zang et al. 2015)

a Superhydrophobic recycled cellulose aerogel. b Flexibility of the large-scale cellulose aerogel (38 cm × 38 cm × 1 cm) containing 0.60wt% of the cellulose fibers. SEM images of the cellulose aerogels with different ratios of cellulose fibers (wt%) and Kymene (μl): c 0.25:5, d 1.00:5, e 0.60:5, and f 0.60:20. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Feng et al. 2015)

Oil absorption process of the recycled cellulose aerogel having 5.0wt% of the cellulose fibers in the artificial seawater (3.5% NaCl and pH 7) mixed with the 5w40 motor oil and dyed with Sudan Red G before testing. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Feng et al. 2015)

Preparation of MCF aerogel (a–d I hydrothermal treatment; II freeze-drying process; III pyrolysis), the morphologies of aerogel before and after thermal treatment (e, f bamboo fiber aerogel; g, h MCF aerogel), and nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of MCF aerogel (i). Reproduced with permission of RSC from (Yang et al. 2015a)

Surface wettability of aerogels to different probe liquids. a Adsorption of water stained with methylene blue by fiber aerogel. b Water droplets on a MCF aerogel. c Interaction between MCF aerogel and liquid after immersing into water. d, e Behavior of water and oil droplets on MCF aerogel. Reproduced with permission of RSC from (Yang et al. 2015a)

Recyclability of MCF aerogel using different methods and corresponding morphologies after cyclic operation for 6 times. a, b Hexane-adsorbed MCF aerogel recycled by distillation. c, d Hexadecane-adsorbed MCF aerogel recycled by combustion. e, f Gasoline adsorbed MCF aerogel recycled by squeezing). Reproduced with permission of RSC from (Yang et al. 2015a)

Photographs showing the regeneration of MCF aerogel via combustion (a) and squeezing (b). Reproduced with permission of RSC from (Yang et al. 2015a)

Selective oil sorption from the oil/water mixture by PDMS-coated absorbent cotton. a The set-up of home-built oil-filter. b Oil remained on the SiO2 layer after the sorption process pump oil (dyed red) without filter. c–e The sorption process using the filter fabricated with the dip-coated absorbent cotton. f Filtered clean water in the beaker after the sorption process. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier from (Lee et al. 2016)

4 Conclusions and further outlook

Oil spill removal is a serious issue where the well-being of the environment is placed at risk due to the toxicity of these compounds causing critical effects to the sea flora and fauna, human health, and also economic losses. In this regard, advanced and “smart” materials are required in order to offer products capable of attending to this problem. Distinct materials have been used for oil absorption with different properties that make them suitable for certain conditions or oil residues due to their properties such as large surface area, porosity and hydrophobicity. Although, in recent years, the search for eco-friendly and low-cost materials promotes the investigation of methods of synthesis with low-impact on the environment, some researchers proposed the use of natural materials such as plants and clays for the development of novel absorbents with reversible oil absorption properties. Additional treatments can improve their hydrophobicity, leading to low-cost absorbents possessing high absorption capacity, and reusability. The use of CVD and deposition of thin layers of hydrophobic nanoparticles on the internal surface of these materials is useful for their conversion from hydrophilic to hydrophobic materials, as well the oil absorption capacity of the material can be increased.

Even though much development has been achieved in this field, many materials are not applicable in the real field due to the limits of mass production and price. There are some materials which have potential for scale-up and commercialization. As future works in this area, plants with naturally porous structures and large surface area seem to be very promising source to create new reversible absorbents based on natural materials using the CVD or dip-coating methods.

References

Abdelwahab O. Assessment of raw luffa as a natural hollow oleophilic fibrous sorbent for oil spill cleanup. Alex Eng J. 2014;53(1):213–8. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2013.11.001.

Adebajo MO, Frost RL, Kloprogge JT, Carmody O, Kokot S. Porous materials for oil spill cleanup: a review of synthesis and absorbing properties. J Porous Mater. 2003;10(3):159–70. doi:10.1023/A:1027484117065.

Alayande SO, Dare EO, Msagati TAM, Akinlabi AK, Aiyedun PO. Superhydrophobic and superoleophilic surface of porous beaded electrospun polystyrene and polysytrene-zeolite fiber for crude oil–water separation. Phys Chem Earth. 2016;92:7–13. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2015.10.002.

Al-Haddad A, Chmielewska E, Al-Radwan S. A brief comparable lab. examination for oil refinery wastewater treatment using the zeolitic and carbonaceous adsorbents. Pet Coal. 2007;49(1):21–6.

Angelova D, Uzunova S, Staykov S, Uzunov I. Preparation of a biogenic carbon/silica based adsorbent for removal of petroleum products spills from aqueous medium. J Univ Chem Technol Metall. 2010;45(1):25–32.

Behnood R, Anvaripour B, Jaafarzade N, Fard H. Application of natural sorbents in crude oil adsorption. Iran J Oil Gas Sci Technol. 2013;2(4):1–11. doi:10.22050/ijogst.2013.4792.

Carmody O, Frost R, Xi Y, Kokot S. Adsorption of hydrocarbons on organo-clays—implications for oil spill remediation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;305(1):17–24. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2006.09.032.

Ceylan D, Dogu S. Evaluation of butyl rubber as sorbent material for the removal of oil and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from seawater. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(10):3846–52. doi:10.1021/es900166v.

Chen M, Jiang W, Wang F, Shen P, Ma P, Gu J, et al. Synthesis of highly hydrophobic floating magnetic polymer nanocomposites for the removal of oils from water surface. Appl Surf Sci. 2013;286:249–56. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.09.059.

Cho YK, Park EJ, Kim YD. Removal of oil by gelation using hydrophobic silica nanoparticles. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(4):1231–5. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2013.08.005.

Feng J, Nguyen ST, Fan Z, Duong HM. Advanced fabrication and oil absorption properties of super-hydrophobic recycled cellulose aerogels. Chem Eng J. 2015;270:168–75. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2015.02.034.

Fingas M. The basics of oil spill cleanup. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2012. p. 286.

Franco CA, Cortés FB, Nassar NN. Adsorptive removal of oil spill from oil-in-fresh water emulsions by hydrophobic alumina nanoparticles functionalized with petroleum vacuum residue. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;425:168–77. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2014.03.051.

Fu Y, Chung DDL. Coagulation of oil in water using sawdust, bentonite and calcium hydroxide to form floating sheets. Appl Clay Sci. 2011;53(4):634–41. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2011.05.014.

Galblaub OA, Shaykhiev IG, Stepanova SV, Timirbaeva GR. Oil spill cleanup of water surface by plant-based sorbents: Russian practices. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2016;101:88–92. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2015.11.002.

Ge J, Ye YD, Yao HB, Zhu X, Wang X, Wu L, et al. Pumping through porous hydrophobic/oleophilic materials: an alternative technology for oil spill remediation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(14):3612–6. doi:10.1002/anie.201310151.

Ifelebuegu AO, Nguyen TVA, Ukotije-Ikwut P, Momoh Z. Liquid-phase sorption characteristics of human hair as a natural oil spill sorbent. J Environ Chem Eng. 2015;3(2):938–43. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2015.02.015.

Kabiri S, Tran DNH, Altalhi T, Losic D. Outstanding adsorption performance of graphene–carbon nanotube aerogels for continuous oil removal. Carbon. 2014;80(1):523–33. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2014.08.092.

Keshavarz A, Zilouei H, Abdolmaleki A, Asadinezhad A. Enhancing oil removal from water by immobilizing multi-wall carbon nanotubes on the surface of polyurethane foam. J Environ Manag. 2015;157:279–86. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.030.

Korhonen JT, Kettunen M, Ras RHA, Ikkala O. Hydrophobic nanocellulose aerogels as floating, sustainable, reusable, and recyclable oil absorbents. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3(6):1813–6. doi:10.1021/am200475b.

Kudaybergenov KK, Ongarbayev EK. Thermally treated rice husks for petroleum adsorption. Int J Biol Chem. 2012;1:3–12.

Kundu P, Mishra IM. Removal of emulsified oil from oily wastewater (oil-in-water emulsion) using packed bed of polymeric resin beads. Sep Purif Technol. 2013;118:519–29. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2013.07.041.

Lee JH, Kim DH, Han SW, Kim BR, Park EJ, Jeong M-G, et al. Fabrication of superhydrophobic fibre and its application to selective oil spill removal. Chem Eng J. 2016;289:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2015.12.026.

Lei W, Portehault D, Liu D, Qin S, Chen Y. Porous boron nitride nanosheets for effective water cleaning. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1777. doi:10.1038/ncomms2818.

Li H, Liu L, Yang F. Hydrophobic modification of polyurethane foam for oil spill cleanup. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64(8):1648–53. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.05.039.

Li H, Liu L, Yang F. Covalent assembly of 3D graphene/polypyrrole foams for oil spill cleanup. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1(10):3446–53. doi:10.1039/C3TA00166K.

Lin C, Huang CL, Shern CC. Recycling waste tire powder for the recovery of oil spills. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2008;52(10):1162–6. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.06.003.

Liu X, Ge L, Li W, Wang X, Li F. Layered double hydroxide functionalized textile for effective oil/water separation and selective oil adsorption. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015a;7(1):791–800. doi:10.1021/am507238y.

Liu Y, Huang G, Gao C, Zhang L, Chen M, Xu X, et al. Biodegradable polylactic acid porous monoliths as effective oil sorbents. Compos Sci Technol. 2015b;118:9–15. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.08.005.

Machado LCR, Lima FWJ, Paniago R, Ardisson JD, Sapag K, Lago RM. Polymer coated vermiculite–iron composites: novel floatable magnetic adsorbents for water spilled contaminants. Appl Clay Sci. 2006;31(3–4):207–15. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2005.07.004.

Moura FCC, Lago RM. Catalytic growth of carbon nanotubes and nanofibers on vermiculite to produce floatable hydrophobic “nanosponges” for oil spill remediation. Appl Catal B Environ. 2009;90(3–4):436–40. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.04.003.

Muhammad IM, El-Nafaty UA, Abdulsalam S, Makarfi YI. Removal of oil from oil produced water using eggshell. Civ Environ Res. 2012;2(8):52–64.

Nikkhah AA, Zilouei H, Asadinezhad A, Keshavarz A. Removal of oil from water using polyurethane foam modified with nanoclay. Chem Eng J. 2015;262:278–85. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2014.09.077.

Nwadiogbu JO, Ajiwe VIE, Okoye PAC. Removal of crude oil from aqueous medium by sorption on hydrophobic corncobs: equilibrium and kinetic studies. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2016;10(1):56–63. doi:10.1016/j.jtusci.2015.03.014.

Okiel K, El-Sayed M, El-Kady MY. Treatment of oil–water emulsions by adsorption onto activated carbon, bentonite and deposited carbon. Egypt J Pet 2011;20(2):9–15. doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2011.06.002.

Olalekan AP, Dada AO, Adesina OA. Review: silica aerogel as a viable absorbent for oil spill remediation. J Encapsulation Adsorpt Sci. 2014;4(4):122–31. doi:10.4236/jeas.2014.44013.

Radetic M, Ilic V, Radojevic D, Miladinovic R, Jocic D, Jovancic P. Efficiency of recycled wool-based nonwoven material for the removal of oils from water. Chemosphere. 2008;70(3):525–30. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.07.005.

Raj KG, Joy PA. Coconut shell based activated carbon–iron oxide magnetic nanocomposite for fast and efficient removal of oil spills. J Environ Chem Eng. 2015;3(3):2068–75. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2015.04.028.

Rao AV, Hegde ND, Hirashima H. Absorption and desorption of organic liquids in elastic superhydrophobic silica aerogels. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;305(1):124–32. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2006.09.025.

Rengasamy RS, Das D, Praba Karan C. Study of oil sorption behavior of filled and structured fiber assemblies made from polypropylene, kapok and milkweed fibers. J Hazard Mater. 2011;186(1):526–32. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.11.031.

Ribeiro TH, Rubio J, Smith RW. A dried hydrophobic aquaphyte as an oil filter for oil/water emulsions. Spill Sci Technol Bull. 2003;8(5–6):483–9. doi:10.1016/S1353-2561(03)00130-0.

Rotar O, Rotar V, Iskrizhitsky A, Pimenova A. Adsorption of hydrocarbons using natural adsorbents of plant origin. Procedia Chem. 2015;15:231–6. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2013.08.005.

Rotar OV, Iskrizhitskaya DV, Iskrizhitsky AA, Oreshina AA. Cleanup of water surface from oil spills using natural sorbent materials. Procedia Chem. 2014;10:145–50. doi:10.1016/j.proche.2014.10.025.

Rotaru A, Cojocaru C, Cretescu I, Pinteala M, Timpu D, Sacarescu L, Harabagiu V. Performances of clay aerogel polymer composites for oil spill sorption: experimental design and modeling. Sep Purif Technol. 2014;133:260–75. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2014.06.059.

Sayyad Amin J, Vared Abkenar M, Zendehboudi S. Natural sorbent for oil spill cleanup from water surface: environmental implication. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015;54(43):10615–21. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01715.

Teisala H, Tuominen M, Kuusipalo J. Superhydrophobic coatings on cellulose-based materials: fabrication, properties, and applications. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2014;1(1):1–20.

Uzunov I, Uzunova S, Angelova D, Gigova A. Effects of the pyrolysis process on the oil sorption capacity of rice husk. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2012;98:166–76. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2012.07.007.

Wahi R, Chuah LA, Choong TSY, Ngaini Z, Nourouzi MM. Oil removal from aqueous state by natural fibrous sorbent: an overview. Sep Purif Technol. 2013;113:51–63. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2013.04.015.

Wang B, Karthikeyan R, Lu XY, Xuan J, Leung MKH. Hollow carbon fibers derived from natural cotton as effective sorbents for oil spill cleanup. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2013;52(51):18251–61. doi:10.1021/ie402371n.

Wang D, McLaughlin E, Pfeffer R, Lin YS. Adsorption of oils from pure liquid and oil–water emulsion on hydrophobic silica aerogels. Sep Purif Technol. 2012;99:28–35. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2012.08.001.

Wang D, Silbaugh T, Pfeffer R, Lin YS. Removal of emulsified oil from water by inverse fluidization of hydrophobic aerogels. Powder Technol. 2010;203(2):298–309. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2010.05.021.

Wang H, Wang E, Liu Z, Gao D, Yuan R, Sun L, Zhu Y. A novel carbon nanotubes reinforced superhydrophobic and superoleophilic polyurethane sponge for selective oil–water separation through a chemical fabrication. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3(1):266–73.

Yang S, Chen L, Mu L, Hao B, Ma PC. Low cost carbon fiber aerogel derived from bamboo for the adsorption of oils and organic solvents with excellent performances. RSC Adv. 2015a;5(48):38470–8. doi:10.1039/C5RA03701H.

Yang Y, Liu Z, Huang J, Wang C. Multifunctional, robust sponges by a simple adsorption–combustion method. J Mater Chem A. 2015b;3(11):5875–81. doi:10.1039/C5TA00454C.

Zadaka-Amir D, Bleiman N, Mishael YG. Sepiolite as an effective natural porous adsorbent for surface oil-spill. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013;169:153–9. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.11.002.

Zang D, Liu F, Zhang M, Gao Z, Wang C. Novel superhydrophobic and superoleophilic sawdust as a selective oil sorbent for oil spill cleanup. Chem Eng Res Des. 2015;102:34–41. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2015.06.014.

Zeng X, Wu D, Fu R. Preparation and characterization of petroleum-pitch-based carbon aerogels. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;112(1):309–14. doi:10.1002/app.29436.

Zhang A, Chen M, Du C, Guo H, Bai H, Li L. Poly(dimethylsiloxane) oil absorbent with a three-dimensionally interconnected porous structure and swellable skeleton. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(20):10201–6. doi:10.1021/am4029203.

Zhao MQ, Huang JQ, Zhang Q, Luo WL, Wei F. Improvement of oil adsorption performance by a sponge-like natural vermiculite–carbon nanotube hybrid. Appl Clay Sci. 2011;53(1):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2011.04.003.

Zhou X, Wang F, Ji Y, Wei J. Fabrication of unidirectional diffusion layer onto polypropylene mat for oil spill cleanup. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015;54(47):11772–8. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03778.

Zhu G, Xi C, Liu Y, Bao C, Shen X, Ma L, et al. Easy fabrication of ultralight CN x foams with application as absorbents and continuous flow oil–water separation. Mater Today Commun. 2015;4:116–23. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2015.06.001.

Zuo L, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Miao YE, Fan W, Liu T. Polymer/carbon-based hybrid aerogels: preparation, properties and applications. Materials. 2015;8(10):6806–48. doi:10.3390/ma8105343.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (Monterrey city, Mexico) for financial support (Project Paicyt-2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Yan-Hua Sun

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cortez, J.S.A., Kharisov, B.I., Quezada, T.E.S. et al. Micro- and nanoporous materials capable of absorbing solvents and oils reversibly: the state of the art. Pet. Sci. 14, 84–104 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-016-0143-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-016-0143-0