Abstract

This paper studies the economic effect of immigration on native working conditions, focusing on the impact of the inflow of immigrant labour on occupational mobility among native workers. Basing on a gender-segmented labour market, we propose an extension of the model presented by Peri and Sparber American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 135-169, (2009). The model controls for gender and time in order to check for potential differences in immigration effects associated with gender or immigrant length of residence. This research reveals the existence of such differences, by showing that female immigrant inflow has a greater positive short-term impact on occupational mobility among female unskilled native workers. In addition, the long-term study discloses a slight occupational assimilation of male immigrants towards employment patterns of male native workers and a permanent confinement of female immigrants in a few “niche jobs”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Low-skilled workers are considered as those who do not have a university degree.

Under the assumption that competition between native and immigrant workers occurs in low-skilled jobs, the model focuses, for the sake of simplicity, on goods requiring only low-skilled factors of production. This leads to the implicit assumption that goods requiring high-skilled factors of production are produced by highly qualified native workers. For this reason, capital is not included in the production function.

Given that the INE replaced CNO-94 with CNO-11 in the first quarter of 2011, we decided to convert the data for 2011 into CNO-94, using the conversion table provided by the same source, and thus enable comparison of our results for the 3 years of the sample period.

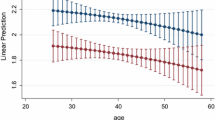

These are incorporated by means of dummy variables. Age takes a value of 1 when the average age for the province is higher than the national average. Educational attainment is included by means of a dummy variable based on provincial percentages of workers without a university degree, which takes a value of 1 if there is a higher percentage than the national average. The expected sign of the coefficient of these two dummies is negative for the first and positive for the second. Thus, a provincial working population that is older and more highly educated than the national average brings about a reduction in the proportion of native workers employed in manual jobs.

Note that \( Ln{\left(\frac{M}{NM}\right)}_{N, it}\kern0.5em =Ln{\left(\frac{\frac{M}{N+NM}}{\frac{NM}{N+NM}}\right)}_{N, it}\kern0.5em =Ln{\left(\frac{N}{N+NM}\right)}_{N, it}-Ln{\left(\frac{N}{N+NM}\right)}_{N, it} \); therefore, it should be the case that β = β M − β NM.

Besides, we have tested previously whether the fixed effects model proves more suitable than a pooled panel data one, and it has been verified that the specification of the model is improved if heterogeneity among provinces and periods is taken into account. Both effects, individual and temporal, are significant. Heteroscedasticity, autocorrelation and normality are also tested. Results suggest that errors have a normal distribution and they are not correlated. Heteroscedasticity is detected in panel data analysis, so heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors are used.

With a view to analyzing the robustness of these results, we also estimated Eq. (5). We confirmed that the relative provision of non-manual tasks by native workers, both male and female, increases as the proportion of immigrant workers increases. The results are not shown here for reasons of space but they are available on request to the authors.

References

Aldaz, L. (2013). Segregación Ocupacional e Inmigración en el Mercado de Trabajo Español. Una Perspectiva de Género. Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De la Rica, S. (2007). Labor market assimilation of recent immigrants in Spain. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 257–284.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De la Rica, S. (2011). Complements or substitutes? Task specialization by gender and nativity in Spain. Labour Economics, 18, 697–707.

Barrett, A., Bergin, A., & Kelly, E. (2011). Estimating the impact of immigration on wages in Ireland. Economic and Social Review, 42(1), 1–26.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–1717.

Borjas, G. J. (1999). The Economic Analysis of Immigration. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of Labour Economics (pp. 1697–1760). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Borjas, G. J. (2003). The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 11(14), 1335–1374.

Borjas, G. J., & Katz, L. F. (2007). The Evolution of the Mexican-Born Workforce in the United States. In G. J. Borjas (Ed.), Mexican Immigration to the United States (pp. 13–55). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Card, D. (2005). Is the new immigration really so bad. The Economic Journal, 115, 300–323.

Card, D., & DiNardo, J. E. (2000). Do immigrant inflows lead to native outflows? American Economic Review, 90(2), 360–367.

Card, D., & Lewis, E. G. (2007). Mexican Immigration to the United States. In G. J. Borjas (Ed.), Mexican Immigration to the United States (pp. 193–227). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carrasco, R., Jimeno, J. F., & Ortega, C. (2008). The effect of immigration on the labor market performance of native-born workers: some evidence for Spain. Journal of Population Economics, 21(3), 627–648.

Casado, M., González, M., Molina, L., & Oyarzun, J. (2005). Análisis Económico de la Inmigración en España: Una Propuesta de Regulación. Madrid: Ediciones UNED.

D’Amuri, F., & Peri, G. (2010). Immigration and occupations in Europe. Centre of Research and Analysis of Migration Working Paper, 26/10.

D’Amuri, F., Ottaviano, G., & Peri, G. (2010). The labor market impact of immigration in Western Germany in the 1990s. European Economic Review, 54(4), 550–570.

Doeringer, P. B., & Piore, M. J. (1971). Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. Lexington: Heath Lexington Books.

Eguía, B., Aldaz, L., & Murua, J. R. (2011). Decomposing changes in occupational segregation: the case of Spain (1999-2010). European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 38, 72–91.

Fajnzylber, P., & Montes Rojas, G. (2006). Microenterprise dynamics in developing countries: how similar are they to those in the industrialized world? Evidence from México. The World Bank Economic Review, 20, 389–419.

Gang, I., Rivera-Batiz, F., & Yun, M. (1999). Immigrants and unemployment in the European Community: from the eyes of natives. Institute for the Study of Labor Working Paper, 70.

González, L. & Ortega, F. (2008). How do Very Open Economies Absorb Large Immigration Flows? Recent Evidence from Spanish Regions. IZA Discussion Paper, 3311.

Gordon, D., Edwards, R., & Reich, M. (1986). Trabajo Segmentado y Trabajadores Divididos. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social de España.

Iglesias, C., & Llorente, R. (2008). The impact of economic immigration on labour opportunities of native-born workers: the Spanish case. Institute of Social and Economic Analysis Working Paper, 05/2006.

Lewis, E. (2003). Local open economies within the US: how do industries respond to immigration?. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper, 04-1.

Manacorda, M., Manning, A., & Wadsworth, J. (2012). The impact of immigration on the structure of male wages: theory and evidence from Britain. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 120–151.

Ortega, F., & Peri, G. (2009). The Causes and Effects of International Labor Mobility: Evidence from OECD Countries 1980-2005. Working Paper, 14833. Cambridge: The National Bureau of Economic Research.

Peri, G., & Sparber, C. (2009). Task specialization, immigration and wages. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 135–169.

Pischke, J. (1993). Assimilation and the Earnings of Guestworkers in Germany. Boston: MIT.

Pischke, J., & Velling, J. (1994). Wage and employment effects of immigration to Germany: an analysis based on local labour markets. Centre for Economic Policy Research Working Paper, 935.

Taubman, P., & Wachter, M. L. (1986). Segmented Labor Markets. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of Labour Economics (pp. 1183–1217). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Tu, J. (2007). The impact of immigration on the labour market outcomes of native-born Canadians. Social and Economic Dimensions of an Aging Population Research Working Paper, 216.

Vedder, R., Gallaway, L., & Moore, S. (2000). The immigration problem: then and now. The Independent Review, 4(3), 347–364.

Venturini, A., & Villosio, C. (2002). Are immigrants competing with natives in the Italian labour market? The employment effect. Institute for the Study of Labor Working Paper, 467.

Winter-Ebmer, R., & Zweimüller, J. (1994). Do Immigrants Displace Native Works? The Austrian Experience. Working Paper, 991. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (EHU14/46). We also would like to thank Felipe Serrano and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Funding

The study was funded by Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (EHU14/46).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aldaz Odriozola, L., Eguía Peña, B. Immigration and Occupational Mobility of Native Workers in Spain. A Gender Perspective. Int. Migration & Integration 17, 1181–1193 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0459-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0459-4