Abstract

Real estate development and the construction of commercial and residential buildings largely determine the future spatial distribution of job and residential locations, thereby giving public planners an instrument with which they can steer urbanization. This paper measures whether the real estate development and urban management planning process, in terms of construction permits, enables a relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments and thus between future job and residential locations. We use data on construction permits for the Netherlands over 1990–2012. Our conclusion is that the real estate development and urban planning process, in terms of construction permits, allows a complementary effect between commercial and residential real estate developments. A one per cent increase in commercial real estate development permits leads to a 0.35 per cent increase in residential real estate development permits. Finally, the data reveal differences across regions suggesting that different local factors are at work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Real estate development, or the process of land development to construct commercial and residential buildings, shapes tomorrow’s urban scene. This is because real estate development governs future land-use and the associated spatial distribution of jobs and houses. As such, it provides public planners with an instrument to steer urbanization. More specifically, real estate development allows public planners to provide residents with a sense of cohesion and security, to contribute to job creation and a more prosperous and viable economy, and to a more sustainable and energy-efficient built environment (Power 2004). As a consequence, real estate development is intrinsically linked to almost every major area of government policy (see, for the Netherlands, Rijksoverheid 2012). A specific public policy aim is to improve the conditions in which people live, work and relax, suggesting a spatial link between residential and commercial real estate development. The focus of this paper is on the relationship between commercial and residential regional real estate developments.

To address this issue, we build upon the literature regarding the spatial distribution of jobs and people. First, we draw on the planning literature that addresses how urban planning and development management affects the job-housing balance (where people live and where they work) and associated implications for future commuting patterns (see Cervero 1995; Zhao et al. 2011). This so-called job-housing balance, which measures the distribution of employment (jobs) relative to the distribution of workers (households) in terms of spatial proximity, depends on the relationship between commercial and residential real estate development. Urban planning and development instruments, such as zoning, height and density restrictions and growth moratoria, all influence commercial and residential real estate development. These regulations typically also regulate land-use and thereby land-use changes, implying that commercial and residential real estate developments competeFootnote 1 (see Evans 2004) in terms of land, labour and development finance (Meen 2002). Such land-use regulations create a substitution (crowding-out) effect between commercial and residential real estate development activities and thus affect the distribution of where people live and work.

Second, the geography and economic literature addresses how people and firms make locational choices. These studies stress the behavioural and dynamic relationship between jobs and people, and question whether people follow jobs, or jobs follow people (Hoogstra 2013). Haig (1926) argued that space and time constraints result in people and jobs being within close proximityFootnote 2. In addition, Papageorgiou and Thisse (1985) suggest that households are attracted to places with a high density of firms (agglomeration economies) because of better job opportunities. Furthermore, the literature also suggests that firms are attracted to places with a high density of households because the generated business volume is expected to be higher. In other words, employees (households) want to live in places with many good choices of work, while firms like to locate where many good potential employees live. So firms will locate near people and people will locate near firms, creating a complementary effect in the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments, and thus where people live and work.

Studies on the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments have considered whether commercial and residential real estate developments substitute or complement each other, and contradictory findings can be observed. Green (1997) concluded that commercial and residential investments are positively correlated over time,Footnote 3 with Coulson and Kim (2002) finding similar results. Wigren and Wilhelmsson (2007), however, found a crowding-out or substitution effect within the European construction industry. Meen (2002)Footnote 4 who had considered industrial real estate development had suggested something similar in the relationship between industrial real estate and residential real estate development. Gyourko (2009)Footnote 5 noted that although commercial and residential real estate markets do show differences they indeed share fundamentals suggesting a substitution effect between commercial and residential real estate developments.

We contribute to this debate by considering whether commercial and residential real estate developments are complementary or substitute for each other. We consider the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments on a regional level. Following Broitman and Koomen (2014), we believe that it is important to disaggregate national level data to regional areas as real estate development differs substantially over space. Disaggregation is important as political and economic conditions, including supply, agglomeration economies, land use regulations and local governments, play an important role (Mayer and Somerville 2000; Vermeulen and Ommeren 2009). As such, addressing the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments on a regional basis will enable the measurement of any regional substitution or complementary effects in that relationship and thus in the spatial distribution of jobs and households.

Regional markets (The Randstad). The Amsterdam Region includes the following municipalities: Aalsmeer, Amstelveen, Amsterdam, Beemster, Diemen, Edam-Volendam, Graft-De Rijp, Haarlemmermeer, Landsmeer, Oostzaan, Ouder-Amstel, Purmerend, Uithoorn, Waterland and Zeevang. The Rotterdam region consists of the following municipalities: Albrandswaard, Barendrecht, Bernisse, Binnenmaas, Brielle, Capelle aan den IJssel, Cromstrijen, Dirksland, Goedereede, Hellevoetsluis, Korendijk, Krimpen aan den IJssel, Lansingerland, Maassluis, Middelharnis, Nederlek, Nieuwekerk aan den IJssel, Oostflakkee, Oud-Beijerland, Ouderkerk, Ridderkerk, Rotterdam, Rozenburg, Schiedam, Spijkenisse, Strijen, Vlaardingen and Westvoorne. The Utrecht region covers the following municipalities: Abcoude, Amersfoort, Baarn, De Bilt, Breukelen, Bunnik, Bunschoten, Eemnes, Houten, IJsselstein, Leusden, Loenen, Lopik, Maarsen, Montfoort, Nieuwegein, Oudewater, Renswoude, Rhenen, De Ronde Venen, Soest, Utrecht, Utrechtse Heuvelrug, Veenendaal, Vianen, Wijk bij Duurstede, Woerden, Woudenberg and Zeist

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, in Sect. 2 below, we describe the main trends in the data. Section 3 then presents the empirical methodology to model the relationship between commercial and residential real estate development. Section 4 presents the empirical results, and our conclusions are presented in Sect. 5.

2 Data and descriptives

2.1 Randstad area in The Netherlands

The Netherlands is among the world’s most urbanized countries, with its most highly urbanized area, denoted as the Randstad, located in the west. The Randstad includes three major metropolitan areas as shown in Fig. 1. The Randstad covers 9.5 per cent of the country’s land area and is home to approximately 23 per cent of the population (based on Statistics Netherlands 2008) and includes both Schiphol Airport and the Port of Rotterdam. In terms of economic activity, the three regions account for 25 per cent of all jobs in the Netherlands, and 29 per cent of the total value added (Amsterdam 11.2 per cent, Rotterdam 9.1 per cent and Utrecht 8.5 per cent).

2.2 Descriptive analysis

The data used include residential and commercialFootnote 6 real estate developments in The Netherlands over the period from 1990 to 2012 and come from public sources. We measure real estate development in terms of the investment value of new housing and new commercial buildings. Data on residential and commercial real estate investment come from Statistic Netherlands and are based on construction permits. Construction permits for investments with a value over €50,000 are issued by Dutch municipalities and include information about the type of building (residential or commercial), the investment value, the region and the month. As a control variable, we use the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of the demand side of real estate development. Data on national GDP are available from Statistics Netherlands. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and all monetary values have been deflated to 1990 values using the consumer price index.

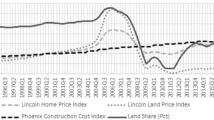

The descriptive statistics reveal a number of empirical patterns in real estate development. First, from the descriptive statistics, we observe that residential real estate development is considerably larger than commercial real estate development. From the lower rows in Table 1, one can see that for each €1 spent on commercial real estate development almost €1.50 goes on residential real estate. Second, regional differences are also apparent with residential real estate development in Amsterdam being relatively small. In Amsterdam, residential and commercial real estate development investments are similar, whereas in Rotterdam and Utrecht residential real estate development is much higher. Further, we observe that commercial real estate development in Amsterdam, in absolute investment value, is considerably larger than in Rotterdam or Utrecht. The metropolitan areas of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht account for one-quarter of national residential and commercial real estate developments. Third, one can also observe variation over time. Figure 2 shows real estate development over the 1990–2012 period for Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht for both residential (left panel) and commercial real estate development (right panel). In the left panel, one sees a rather stable profile until the late-1990s, after which residential real estate development almost doubled until the global financial crisis hit leading to a considerable fall in residential real estate development. The right panel of Fig. 2 shows that the global financial crisis led to an even sharper fall in commercial real estate development. Based on the coefficients of variation in residential and commercial real estate development, one observes larger volatility in commercial real estate development (Table 1).

Real residential (left panel) and commercial (right panel) real estate development. This figure shows investments in real estate development for Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and The Netherlands as a whole for 1990–2012. In 1990, the values of investments in residential real estate development were: for Amsterdam €388 million, Rotterdam €312 million, Utrecht €357 million, and The Netherlands €4733 million. For commercial real estate, the 1990 investment value in Amsterdam was €772 million, Rotterdam €346 million, Utrecht €429 million and for The Netherlands €4345 million. All data: Statistics Netherlands

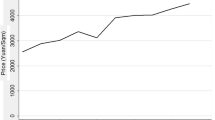

The correlations between the series indicate dependence over time and across sectors. The two right-hand columns in Table 1 address the serial correlation in the series. First, we tested whether the series are stationary. For this, we used the Augmented Dickey-Fuller unit root test statistic for one and two lags to test the null hypothesis of the presence of a unit root. The test indicates that, for most series, the hypothesis that a unit root was present could not be rejectedFootnote 7. Second, we considered the possibility of contemporaneous correlation as presented in Table 2. These statistics reveal positive correlations between residential real estate development and commercial real estate development and between real estate development and (see Fig 3) GDP, but not between commercial real estate development and GDP.

3 Empirical methodology

In exploring the long- and short- run relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments in the Netherlands, we applied a two-stage error correction model. In the first step, we estimated the long-run relationship between residential and commercial real estate development in region \(j\) for period \(t\) while controlling for GDP. This model has the form:

where \(C_{ jt}^r \) is the residential real estate development, \(C_{ jt}^c \) the commercial real estate development and \({ GDP}_t\) the Gross Domestic Product. The coefficient \(\gamma _1 \), which reflects the long-run relationship between residential and commercial real estate developments, provides important information regarding this relationship. A positive coefficient indicates that residential real estate complements commercial real estate whereas a negative estimate would indicate a substitution effect.

In the second step, we incorporate short-term corrections to the long-run equilibrium relationship. These short-term corrections account for the disequilibrium, or speed of adjustment, in the real estate development market to return to equilibrium (Brounen and Jennen 2009). We can only measure these short-term corrections if the trending variables of Eq. (1) are co-integrated. Therefore, we estimate Eq. (1) in first differences while including lagged residuals (short-term corrections) of the long-run modelFootnote 8 as regressor, such that:

where \(u_{jt-1} \) captures the error correction over time. The short-run model tests whether residential real estate development reacts to short-run changes in commercial real estate development, to economic growth, and to the error-correction term. The estimation strategy is thus to first estimate the long-run modelFootnote 9, and subsequently estimate the short-run model.

As already noted in the literature, a jobs following people or people following jobs relationship potentially creates an endogeneity problem as the location decisions of households and of firms are likely to be endogenous. As a result, location choices, or the associated commercial and residential real estate developments, will result in biased parameters. What is needed is a proxy that does not suffer from this potential problem. We address this potential endogeneity problem by adopting an instrumental variable approach using lagged values of commercial real estate development as an instrument for commercial real estate developmentFootnote 10. First, we tested if the instrument is valid, because when the instrument is only weakly correlated with commercial real estate development, the estimates will be biased (Wooldridge 2008). We tested for this eventuality using the F test for weak instruments and the minimum eigenvalue statistic (Stock and Yogo 2005). Second, we used the Durbin Wu-Hausman test to see whether a variable presumed to be endogenous (commercial real estate development) should be treated as exogenous. If commercial real estate development is exogenous, the ordinary least square (OLS) estimates of the two-stage error correction model are more efficient than the instrumental variable approach.

4 Estimation results

Panel A of Table 3 contains the results for the long-run model, and the corresponding short-run model results are shown in Panel B. To ensure reliable estimates we also used instrumental variables in estimating the relationship between residential and commercial real estate developments (see Appendix 6). As instrument, we included the lagged values of commercial real estate development. The outcomes of the instrumental variable approach show the following. First, there is no evidence that lagged values of commercial real estate development are an insufficient instrument for commercial real estate development (the F value is 12.75). Second, the result of the Hausman endogeneity test is 0.01, which is far below the five per cent confidence critical value of 3.84. Consequently, we feel justified in treating commercial real estate investments as exogenous, and in relying on the two-stage error correction model for our estimates. The long-run models have explanatory powers (\(\hbox {R}^{2}\)-adj) ranging from 0.19 to 0.51, and the short-run models have \(\hbox {R}^{2}\)-adj values from 0.13 to 0.33. Overall, the results suggest that the models have joint significance and that a naïve model should be rejected.

We now discuss the results for the long-run model as provide in Table 3: Panel A. Here, we correct for possible demand for space effects by including GDP. The effect found of GDP on residential real estate development activity was positive, and in line with earlier literature (see Riddel 2004; Wigren and Wilhelmsson 2007). We are particularly interested in the parameter for commercial real estate, \(\hbox {C}_{\mathrm{jt}}^c \), as this summarizes the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments. The estimation results indicate a positive relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments. This was true in all regions tested and for both specifications of commercial real estate (model 1: office and industrial; model 2: only office buildings). Thus, there is a relationship between an expansion in commercial real estate and an expansion in residential real estate development activity. After controlling for changes in GDP, we saw, for the Randstad, that a 1 per cent increase in commercial real estate development is mirrored by a 0.35 per cent increase in residential real estate development. This outcome sheds an interesting light on the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments given that the Dutch residential market is strongly impacted by public planning interventions (Vermeulen and Ommeren 2009) with an almost inelastic supply (Vermeulen and Rouwendal 2007). Our results indicate that residential real estate development reacts to commercial real estate development and, as such, this outcome refines the findings of Vermeulen and Ommeren (2009). They used housing stock growth as a proxy for housing supply and found that housing supply was insensitive to changes in employment. We measured real estate development activity using permits rather than completed stock, and used GDP rather than employment, and did find a relationship between the two. The implication of this is that not all real estate development activity result in new residential or commercial stock. Our main finding is that having permits in the real estate development and urban management planning process allows a connection between commercial and residential real estate developments.

We also observed regional differences: whereas the data on the Rotterdam and Utrecht regions indicate a significant positive effect of commercial real estate development, the data on the Amsterdam region do not suggest a significant effect. This underlines that real estate development is a local phenomenon in which local government policies and land-use regulations govern land-use and real estate development. From a broader perspective, this is precisely the pattern one would expect to find as a result of differences in demographics and other local real estate market fundamentals.

The results of the short-run model in Table 3: Panel B highlight important differences in the short- and long- run relationships between residential and commercial real estate developments. First, we see that the short-run commercial real estate development dynamic coefficient \(\left( \Delta \hbox {Ln}(\hbox {C}_{\mathrm{jt}}^c )\right) \) is positive but not always as statistically significant as in the long-run model. This suggests that either the effect size of the relationship between commercial and residential real estate development is weak, or the sample size is too small. Since we have a small sample size, we still expect a small but positive effect. Such an effect indicates that, even in the short-run, residential and commercial real estate development activities are complementary. Second, GDP has a considerable effect on short-run residential development activities. This short-run effect, which is larger than the long-run effect, is in line with previous findings (Wigren and Wilhelmsson 2007). Third, we have considered whether real estate development activities reflect some notion of equilibrium (see Tiwari and White 2010; Nozeman and Vlist 2014). Such an equilibrium would mean that real estate development to an extent depends on the level of development in previous years. That is, real estate development will be lower when the development in previous years was relatively high, and vice versa. We can test this notion by exploiting information in the residuals of the long-run model and testing for the presence of a unit root. The unit-root testFootnote 11 of the residuals indicates the existence of an error correction. The error-correction parameter for residential real estate development in Model 1 [Pooled (Randstad) region] amounts to \(-\)0.36, indicating a correction of 36 per cent if development is above its steady-state value.

Again, we found large differences between regions. The results indicate a positive and statistically significant estimate for commercial real estate developments in Rotterdam and Utrecht, but not for Amsterdam. Thus, as in Panel A, we found a relationship between commercial and residential real estate development activities, this time in the short-run, although the magnitude of these differ between regions.

5 Conclusions

This paper adds to the literature on the relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments. The literature outlines two competing views regarding this relationship: a substitution effect arising from land-use regulations, in terms of land, labour and development finance, and a complementary effect arising from the fact that firms will locate near people and people will locate near firms. To examine the realities of this relationship, we used regional data, available from public sources, on commercial and residential real estate development permits in the Netherlands over the period from 1990 to 2012.

We used a two-step estimation approach. In the first step, we estimated the long-run relationship between commercial and residential real estate developments. To ensure reliable coefficients, we also tested an instrumental variable approach. In the second step, we estimated a short-run model while incorporating the short-term corrections deduced from the long-run equilibrium model.

We found that, in the long run, residential and commercial real estate developments complement each other. This is in line with the arguments that people follow jobs and/or jobs follow people. This finding has implications for the job-housing balance. The results suggest that households wanting to live and work within close spatial proximity will exert pressure on future land-use as new land for development is limited. Further, our region-specific model shows that, at least in Rotterdam and Utrecht, residential real estate development complements commercial real estate development. Moreover, we also found a short-run complementary effect between residential and commercial real estate developments in Rotterdam and Utrecht. Summarizing our results, we conclude that the real estate development and urban planning process with its use of building permits enables a connection between commercial and residential real estate developments.

Notes

Except for mixed land-use development activities.

Renkow (2003) suggests that recent advances in information communication technology (ICT) and mobility (commuting time) have attenuated these space and proximity constraints and have de-linked the locational choices of firms and households. McCann (2008), in contrast, suggests that density and spatial proximity remain import for innovation, productivity and economic growth. The agglomeration seen in economies suggests that firms locate close to each other in order to gain in productivity and locate near people.

Green (1997) uses a Granger causality test with quarterly data on GDP, residential investment and non-residential investment from 1959 to 1992.

Meen (2002) used the Johansen approach with quarterly data on private and public new housing construction orders, industrial new construction orders, change in manufacturing output and the percentage change in GDP from 1964Q4 to 2001Q1.

Gyourko (2009) carried out correlation and regression tests with annual data from 1978 to 2008 on real estate prices obtained from The National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF), Real Estate Investment Trust (NAREIT) and The Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight repeat sale price index (OFHEO).

In this study, we use the total investment in the commercial real estate sector (all commercial and industrial buildings). However, in the results section, we also include a model that considers only office investments to investigate any differences. The office market accounts for approximately 22 % of the total investments in commercial real estate.

We found that, apart from for the commercial real estate development series in Utrecht, the series were non-stationary. Despite this singular finding, we consider the commercial real estate series as non-stationary since we could not reject a unit root with most series. Given the recognized lack of power in unit root tests with short series, we also used the Hadri stationary test which allows for heterogeneous series. Again, we found clear evidence that the series are non-stationary.

We first test for stationarity in the long-run model’s residuals to determine whether a co-integration relationship is present (see Levin et al. 2002).

We also attempted a Granger causality test to further investigate the relationship but the test lacked sufficient power due to the small number of observations.

We tested several specifications of the instrumental variable approach and instrumented commercial real estate development on its previous lagged values.

The Levin et al. (2002) unit-root test gives a statistic of \(-\)2.487 and \(-\)3.528 with a \(p\) value \(>\) 0.05 indicating that the series is stationary. For the separate regions, we use the ADF unit root test. For Rotterdam, the results (ADF \(=\) \(-\)3.392, \(p\) value \(=\) 0.01) reject the presence of a unit root, whereas for both Amsterdam (ADF = \(-\)2.098, \(p\) value = 0.250) and Utrecht (ADF = \(-\)1.184, \(p\) value \(=\) 0.680), and for The Netherlands as a whole (ADF = \(-\)1.048, \(p\) value \(=\) 0.725), the residuals suggest a unit root.

References

Broitman, D., Koomen, E.: Regional diversity in residential development: a decade of urban and peri- urban housing dynamics in the Netherlands. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. (2014). doi:10.1007/s12076-014-0134-y

Brounen, D., Jennen, M.G.J.: Local office rent dynamics: a tale of ten cities. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 39, 385–402 (2009)

Cervero, R.: Planned communities, self-containment and commuting. Urban Stud. 31, 1135–1161 (1995)

Coulson, E., Kim, M.S.: Residential investment, non-residential investment and GDP. Real Estate Econ. 28(2), 233–248 (2002)

Crown, : National planning policy framework. UK Department for Communities and Local Government, London (2012)

Evans, A.: Economics and land use planning. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford (2004)

Green, R.K.: Follow the leader: how changes in residential and non-residential investment predict changes in GDP. Real Estate Econ. 25(2), 253–270 (1997)

Gyourko, J.: Understanding commercial real estate: just how different from housing is it? J. Portf. Manag. 35(5), 23–37 (2009)

Haig, R.M.: Toward an understanding of the metropolis. Some speculations regarding the economic basis of urban concentration. Q. J. Econ. 40, 179–208 (1926)

Hoogstra, G.: Location changes of jobs and people. PhD Thesis. University of Groningen (2013)

Levin, A., Lin, C.F., Chu, S.S.: Unit root test in panel data: asymptotic and finite sample properties. J. Econom. 108, 1–24 (2002)

Mayer, C.J., Somerville, C.T.: Residential construction: Using the urban growth model to estimate housing supply. J. Urban Econ. 48(1), 85–109 (2000)

McCann, P.: Globalization and economic geography: the world is curved, not flat. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 1, 351–370 (2008)

Meen, G.: On the long-run relationship between industrial construction and housing. J. Prop. Res. 19(3), 191–211 (2002)

Nozeman, E.F., Van der Vlist, A.J.: European metropolitan commercial real estate markets. Advances in spatial science. Springer, Berlin (2014)

Papageorgiou, Y.Y., Thisse, J.F.: Agglomeration as spatial interdependence between firms and households. J. Econ. Theory 37, 19–31 (1985)

Power, A.: Sustainable Communities and sustainable development: a review of the sustainable communities plan. CASE report 23. London School of Economics. Centre for analysis of social exclusion (2004)

Renkow, M.: Employment growth, worker mobility, and rural economic development. A. J. Agric. Econ. 85, 503–513 (2003)

Riddel, M.: Housing-market disequilibrium: an examination of housing market price and stock dynamics 1967–1998. J. Hous. Econ. 13, 120–135 (2004)

Rijksoverheid.: Structuurvisie Infrastructuur en Ruimte. Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu (2012)

Stock, J., Yogo, M.: Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews DWK (ed.) Identification and Inference for Econometric Models. Cambridge University Press , New York (2005)

Tiwari, P., White, M.: International real estate economics. palgrave macmillan, basingstoke (2010)

Vermeulen, W., Van Ommeren, J.: Does land use planning shape regional economies? A simultaneous analysis of housing supply, internal migration and local employment growth in the Netherlands. J. Hous. Econ. 18, 294–310 (2009)

Vermeulen, W., Rouwendal, J.: Housing supply and land use regulation in the Netherlands. Tinbergen Discussion paper, 2007-058/3 (2007)

Wigren, R., Wilhelmsson, M.: Construction investments and economic growth in Western Europe. J. Policy Model. 29, 439–451 (2007)

Wooldridge, J.M.: Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Michigan state University, South-Western Cengage Learning (2008)

Zhao, P., Lu, B., De Roo, G.: Impact of the job-housing balance on urban commuting in Beijing in the transformation era. J. Transp. Geogr. 19, 59–68 (2011)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for many helpful comments from participants of the 2012 European Real Estate Society ERES conference, Edinburgh. The comments of Jan Rouwendal, Henk Folmer, Gerke Hoogstra, Jouke Van Dijk and an anonymous referee on an earlier version are also greatly appreciated. All errors remain the authors. This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Instrumental variables

Appendix A: Instrumental variables

In this appendix, we estimate pooled models (1) and (2) using an instrumental variable approach to test for the possibility of endogeneity problems between commercial and residential real estate developments.

See (Table 4).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenmaker, D.A.J., Van der Vlist, A.J. On real estate development activity: the relationship between commercial and residential real estate markets. Lett Spat Resour Sci 8, 219–232 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-015-0144-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-015-0144-4