Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify subgroups of breast cancer patients and their partners based on distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms, to examine how relationship quality and medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with these trajectories, and to explore whether patients and partners had similar trajectories.

Methods

A nationwide, population-based cohort of couples dealing with breast cancer was established in Denmark. Participants completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale at baseline and 5 and 12 months later. Sociodemographic and medical characteristics were retrieved from registers. A trajectory finite mixture model was used to identify trajectories.

Results

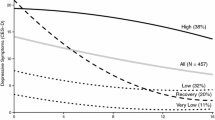

The trajectories of depressive symptoms over time were analyzed in 546 patients and 508 partners. Among patients, 13 % had a high stable trajectory, 38 % an intermediate decreasing trajectory, and 49 % a low trajectory. Similar trajectories were found for partners (11, 22, and 67 %, respectively). Compared to the low trajectory, trajectories with higher depressive symptoms were associated with poorer relationship quality and previous use of antidepressants for patients and partners and with younger age, comorbidity, basic education, and chemotherapy for patients. The trajectories of patients and their partners were weakly correlated.

Conclusions

A considerable minority of patients and partners had a persistently high level of depressive symptoms. Poorer relationship quality and previous antidepressant use most consistently characterized patients and partners with higher depressive symptom trajectories.

Implications for cancer survivors

In clinical practice, attention to differences in depressive symptom trajectories is important to identify and target patients and partners who might need support.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:817–23.

Faller H, Brahler E, Harter M, et al. Performance status and depressive symptoms as predictors of quality of life in cancer patients. A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1456–62.

Mausbach BT, Schwab RB, Irwin SA. Depression as a predictor of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) in women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:239–46.

Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:484–92.

Hinnen C, Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. The role of distress, neuroticism and time since diagnosis in explaining support behaviors in partners of women with breast cancer: results of a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 2007;16:913–9.

Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:920–54.

Pistrang N, Barker C. The partner relationship in psychological response to breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:789–97.

Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:768–77.

Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1517–24.

Hinnen C, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R, et al. Course of distress in breast cancer patients, their partners, and matched control couples. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:141–8.

Millar K, Purushotham AD, McLatchie E, George WD, Murray GD. A 1-year prospective study of individual variation in distress, and illness perceptions, after treatment for breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:335–42.

Manne S, Ostroff J, Fox K, Grana G, Winkel G. Cognitive and social processes predicting partner psychological adaptation to early stage breast cancer. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:49–68.

Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:1–30.

Nakaya N, Saito-Nakaya K, Bidstrup PE, et al. Increased risk for severe depression in male partners of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:5527–34.

Dalton SO, Laursen TM, Ross L, Mortensen PB, Johansen C. Risk for hospitalization with depression after a cancer diagnosis: a nationwide, population-based study of cancer patients in Denmark from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1440–5.

Bonanno GA. Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:135–8.

Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol. 2004;23:3–15.

Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, et al. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2010;29:160–8.

Lam WW, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1044–51.

Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, et al. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2011;30:683–92.

Lam WW, Soong I, Yau TK, et al. The evolution of psychological distress trajectories in women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2831–9.

Donovan KA, Gonzalez BD, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB. Depressive symptom trajectories during and after adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:292–302.

Bidstrup PE, Christensen J, Mertz BG, et al. Trajectories of distress, anxiety, and depression among women with breast cancer: looking beyond the mean. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:789–96.

Yang HC, Schuler TA. Marital quality and survivorship: slowed recovery for breast cancer patients in distressed relationships. Cancer. 2009;115:217–28.

Lewis FM, Fletcher KA, Cochrane BB, Fann JR. Predictors of depressed mood in spouses of women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1289–95.

Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4829–34.

Christensen S, Zachariae R, Jensen AB, et al. Prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms 3-4 months post-surgery in a nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early stage breast-cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:339–55.

Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Mattes ML, et al. Adjusting to life after treatment: distress and quality of life following treatment for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1625–31.

Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, Dimsdale JE, et al. Objective cancer-related variables are not associated with depressive symptoms in women treated for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2420–7.

Mehnert A, Koch U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:383–91.

Moller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, et al. The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG); its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:506–24.

Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:22–5.

Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, et al. Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:2608–13.

Terp H, Rottmann N, Larsen PV, et al. Participation in questionnaire studies among couples affected by breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1907–16.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Heikkinen RL, Berg S, Avlund K. Depressive symptomatology among the elderly in three Nordic localities as measured by the CES-D scale. In: Heikkinen E, Berg E, Schroll M, Steen B, Viidik A, editors. Functional status, health and aging: the NORA study. Paris: Serdi Publisher; 1997. p. 107–19.

Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:437–43.

Kuijer RG, Buunk BP, De Jong GM, Ybema JF, Sanderman R. Effects of a brief intervention program for patients with cancer and their partners on feelings of inequity, relationship quality and psychological distress. Psychooncology. 2004;13:321–34.

Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186–91.

Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Gislum M, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: background, aims, material and methods. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1938–49.

Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Bronnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:12–6.

Rostgaard K, Holst H, Mouridsen HT, Lynge E. Do clinical databases render population-based cancer registers obsolete? The example of breast cancer in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:669–74.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic co-morbidity in longitudinal studies—development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–3.

Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:38–41.

Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:374–94.

Lambert SD, Jones BL, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Distressed partners and caregivers do not recover easily: adjustment trajectories among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:225–35.

Tang ST, Huang GH, Wei YC, et al. Trajectories of caregiver depressive symptoms while providing end-of-life care. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2702–10.

Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Cohen L. Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2003;12:183–93.

Choi CW, Stone RA, Kim KH, et al. Group-based trajectory modeling of caregiver psychological distress over time. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:73–84.

Geller BM, Mace J, Vacek P, et al. Are cancer survivors willing to participate in research? J Community Health. 2011;36:772–8.

Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE, Stanton AL, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. Characteristics of breast cancer survivors that predict partners’ participation in research. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:107–13.

Badr H, Krebs P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1688–704.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Danish Cancer Society. The National Research Centre for Cancer Rehabilitation, University of Southern Denmark, is funded by the Danish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1

Relationship Ladder. (PDF 167 kb)

Online Resource 2

Model selection in the study of the depressive symptom trajectories of 546 women affected by breast cancer and 508 male partners. (PDF 98 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rottmann, N., Hansen, D.G., Hagedoorn, M. et al. Depressive symptom trajectories in women affected by breast cancer and their male partners: a nationwide prospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv 10, 915–926 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0538-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0538-3