Abstract

Urgent change is required in the governance of ocean spaces to contend with the increasing presence and impact of human activities, the solution to which is often labelled a ‘transformation.’ While diverse interpretations of this concept exist across academic disciplines, a grounded exploration of the subject with those involved in ocean governance has not been undertaken and is a critical gap in the practical implementation of the concept. Leverage points have been not only identified as a mechanism for change, but also face similar research challenges. Therefore, this research aimed to identify, through 24 expert and practitioner interviews, what exactly transformation means in the context of ocean governance, and how it can be achieved through a leverage points approach. While reactions to and perceptions of the concept were mixed, several definitions of transformation were identified, ultimately hinging on incremental and radical change to define character. A multi-intervention ‘puzzle’ style of leverage points is advocated for. Therefore, ocean governance transformation is proposed to be achieved through a model that recognises the utility and benefits of both radical and incremental change and employs a multi-leverage approach, using interventions at varying depths across the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The crises facing ocean environments and their communities are numerous, ranging from ecological to social (Campbell et al. 2016; Blythe et al. 2021b). Increasingly unequal access to ocean resources (Virdin et al. 2021), ecosystem biodiversity loss (Erinosho et al. 2021), growing plastic pollution (Dauvergne 2018) and the progressive impacts of climate change (IPCC 2019) all necessitate a re-examination of the ocean governance system (Heinze et al. 2021). Transformative change is proposed as a solution to these crises. The identified goals of such transformative change are diverse, ranging from the creation of a new relationship between humanity and the ocean (IPCC 2019), a globalised approach to ocean governance that emphasises the commons (Rudolph et al. 2020), and turns to economic growth and sustainability under the remit of the blue economy (Gerhardinger et al. 2020). Steps towards realising transformational agendas are being undertaken, as exemplified by the formulation of the High-Level Ocean Panel by 17 heads of state, which advocates for five transformations towards a sustainable ocean economy (High Level Ocean Panel 2020).

Regardless of these growing calls for transformative change, the understanding of what precisely transformative change is and how it is achieved is contested and subject to a plurality of views and ideas (Evans et al. 2023). A growth of transformative literature in recent years has explored the concept from diverse academic perspectives, such as political ecology, organisational change management, and systems thinking. Building on the understanding of Evans et al. (2023), achieving transformation through governance is inseparable from the transforming of ocean governance structures. To date, ocean governance literature has focused on the role of politics in transformative governance (Blythe et al. 2021a, b), defining transformation, localised case studies of transformative processes at different scales (Gelcich et al. 2010, 2019; Blythe et al. 2021b), and reviews of equity and justice (Bennett et al. 2019; Cisneros-Montemayor et al. 2019; Pickering et al. 2022). A rich but emerging understanding of transformation from a biodiversity governance perspective has also contributed to the robust debate regarding the conceptualisation of transformation (Bulkeley et al. 2020; Visseren-Hamakers and Kok 2022).

Despite growing attention, a lack of practitioner-informed perspectives on transformation presents a growing operational risk to calls for change and the efficacy of any future interventions (Evans et al. 2023). Thus, an exploration of what exactly transformation means to those tasked with achieving or implementing transformation is needed. To fill these gaps, a grounded definition of transformation from practitioners' perspectives is critical in understanding how the practical application remains realistic. Fairly standard definitions of transformation from an academic perspective exist, such as O’Brien (2012) and the concept has been applied to ocean governance by Blythe et al. (2021b) and ocean biodiversity governance by Erinosho et al. (2021). Exploring the characteristics of transformative change, its scale, scope and limitations from diverse practitioner experiences is crucial to achieving a substantial theory of how transformation can be achieved in practice.

Building on this operational gap, exploring the “how to” of transformational change has been identified as the most important question in transformative research (Fazey et al. 2018; Boik 2020). No general guidance exists for transformational change beyond site-specific case studies, representing a gap in theory. Recently, leverage points have emerged as a mechanism for transformation (Evans et al. 2023). Significant advances in the understanding of leverage points as a concept have been achieved, with diverse approaches to classifying leverage points including the original hierarchy of depth pioneered by Meadows (1999), the iceberg model reflected on by Davelaar (2021) and Abson et al (2017) seminal hierarchy of leverage points. The discussion of leverage points in the context of transformation is not novel and is a widely accepted model of systems change (Abson et al. 2017; Davelaar 2021; Leventon et al. 2021; Linnér and Wibeck 2021). Leverage points have most recently been explored and included as part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) approach to transformations for biodiversity (Visseren-Hamakers and Kok 2022, p. 69). In ocean governance, leverage points have been explored in addressing marine pollution (Riechers et al. 2021b) but not in achieving governance change.

From a climate perspective, the depth of leverage points has also been mapped into widely accepted spheres of influence by O’Brien (2018), spanning personal, political and practical. It is accepted that targeting deeper leverage points, while more challenging, yields more transformative results (Meadows 1999; Abson et al. 2017; Fischer and Riechers 2019; Dorninger et al. 2020; Davelaar 2021; Riechers et al. 2021a, b). Riechers et al. (2021a, b) also used depth of leverage point as a proxy for transformative potential, with the understanding that the deeper the leverage point, the more widespread the change across the system. This research adopts the classification created by Abson et al. (2017) using, in increasing depth: parameters, feedbacks, design and system intent (described in Table 1). However, no research has been undertaken regarding how leverage points are operationalised and understood by practitioners of ocean governance, or if classifications of depth translate into practice. Therefore, understanding how practitioners understand and use the concept, and the depth of leverage points identified by practitioners is important in understanding what the awareness of depth of change is among the practitioner community.

In summary, this research addresses the lack of discussion around the plurality of views surrounding transformation, particularly when engaging with practitioner perspectives. Through expert interviews, the following research objectives were considered. Firstly, to understand the breadth of definitions and conceptualizations of transformation held by practitioners and experts. Secondly, characteristics of transformation in ocean governance were discussed to provide conceptual clarity to the context and scale of transformative ocean governance. Finally, interviews sought to understand how transformation can be achieved in practice initially through the concept of leverage points. Leverage points are defined here as places in a system where “where a small change could lead to a large shift” across the system (Meadows 2009, p. 145).

Methods

Interviews were conducted with 24 experts, academics, and practitioners (hereafter termed ‘experts’) of marine and ocean governance between January and October 2022. An initial sample of five experts was identified, with the remaining population identified through ‘snowballing’ until interviewees began recommending people who had already been contacted or interviewed (theoretical saturation) (McKinley and Ballinger 2018). It is recognised that defining explicitly what an expert is difficult, and depends upon the confluence of expert knowledge, social power, and trust (Hardoš 2018). Thus, an early pool of experts was initially identified by level and amount of relevant experience, status and reputation. Given the small number of people globally with the relevant level of professional experience needed to participate in this study, the remainder of the sample was identified by ‘snowballing’, which is commonly used for identifying individuals whose target characteristics are not easily accessible (Naderifar et al. 2017).

Interviewees typically had senior-level ocean governance experience in multiple countries. In all cases, interviewees shared ocean governance and transformation insights from multiple countries and regions, with an emphasis on Africa, Europe, North America, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Pacific islands. All interviewees were English speaking as either their first or second language, and all interviews were conducted online given their global distribution.

The final interview population included national and international perspectives, as well as perspectives that were largely conceptual and scale independent, and a breadth of professional experience ranging from independent consultants, marine planners, heads of government departments, advisors and advocates as displayed in Fig. 1. Neither the interviewee's nationality nor current working location reflected the spatial focus of their professional experience, as such, sample representativeness was difficult to determine or claim. However, given that the purpose of the interviews was to explore a diversity of views and practical experiences, the sample was deemed complete once saturation became evident. Prior to submission, five interviewees were asked for validation and refinement of the original draft of the paper and findings and were identified for theory construction. Of the five, two interviewees responded with feedback which facilitated a further refinement and sensitisation of the ideas presented.

Semi-structured interviews were chosen to provide an open-ended method of research that promoted discussion (Charmaz 2014), and the interview protocol was ethically approved by the lead researcher’s host institution. All interviewees were asked about how they would define transformation and discussed the different characteristics identified. Interviewees were asked initially if they were familiar with leverage points as a concept as part of the interview. If interviewees were unfamiliar with the concept, the definition of a leverage point by Meadows (1999) was given. Generally, interviewees were familiar with the concept and defined it similarly to Meadows (1999), as places to intervene in a system where effort is disproportionate to outcome. However, as will be discussed in “Disconnects between theory and practice” section, this understanding is questioned due to observed disconnects between academic theory and interviewee responses.

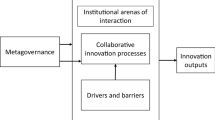

Interviews were analysed using a QSR NVivo. To explore the diverse definitions and understandings of transformation, a three-step iterative coding practice was adopted, which allowed emergent themes to arise and be refined throughout analysis (Denscombe 2010; Saldaña 2021). Leverage points were explored through a similar coding pattern, requiring a process of abstraction and synthesis to compile a final list of categories of leverage points in Fig. 2. This list was then compared against a standard classification of leverage points (Abson et al. 2017, Table 1). This process was challenging, as discussed in “Disconnects between theory and practice” section.

Leverage points identified by interviewees are presented graphically to highlight the multi-leverage point approach proposed through this research, and display the variability in approach required for transformation. The puzzle of leverage points indicates the need to include a range of depth of leverage in pursuit of transformative change. The size of each shape represents the number of interviewees who discussed the leverage point, and is also presented as a number, while colour corresponds to depth according to the hierarchy defined by Abson et al. (2017), and discussed in “The ‘puzzle’ of leverage points” section. Given that culture is not part of Abson et al. (2017) hierarchy, it is presented in grey. Some leverage points are noted multiple times, as they were discussed as part of multiple depths of leverage e.g. law and policy were discussed at both design and implementation level.

The remainder of this paper presents the results and discussion of the interviews in “Defining and grounding transformation in expert perspectives” and “Leverage points” sections. The results and discussion are presented in tandem to avoid excessive repetition and to fully contextualise interviewee understandings against literature. Given the aims of this research, “Defining and grounding transformation in expert perspectives” section will discuss the varying definitions of transformation presented by interviewees, and ground these in the context of literature. “Leverage points” section will then discuss responses regarding leverage points in the context of systemic change. A final synthesis and conclusions in “Radical and incremental: transformation in ocean governance” and “Conclusions” section.

Defining and grounding transformation in expert perspectives

Mixed perspectives of transformation

Contextualising how interviewees understood transformation is important to set the scene for the findings of this research. Perceptions of transformation as a concept were fairly evenly split, with five interviewees identifying both positive and negative attitudes towards transformation, six identifying only positive attitudes, and five identifying only negative attitudes towards transformation. These perceptions could not be attributed to professional background, length of experience, or self-graded knowledge of ocean governance and transformation. Positive perceptions regarded transformation as “needed or necessary” (by seven interviewees), a “powerful concept” (by three interviewees), and “exciting” (by three interviewees).

Negative perceptions towards transformation were generally more varied, ranging from concern to frustration and contempt. Three interviewees identified transformation as being ‘patronising’ in its approach and were suspicious of the concept. The ‘patronising’ nature of transformation was elaborated on by Interviewee 2, who felt that calls to transformation, particularly in the context of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), implies starting over and that “the way you're doing stuff at the moment is completely wrong.” This speaks to a need for a wider conversation about where calls for transformation are coming from, and who makes decisions regarding change (Patterson et al. 2017). There is a risk of an unequal power balance between those calling for transformation, and those subject to transformed states. This finding is echoed by Blythe et al. (2018). From a practical perspective, it is, therefore, important to note the inherent and implicit power created when demands for transformation are made. As Interviewee 11 noted, “My concern and my suspicion [is], what does this mean, and who is calling for it, and why are they calling for it?” The implications of power in transformation are further discussed in “Examining buzzwords” section.

From these general perceptions, it is clear that, in practice, transformation is regarded as a complex subject. There are often conflicting interpretations of how useful the concept is, which highlights the contested sphere in which discussions of transformation take place. In practice, these diverse opinions impact the traction the concept has on the ground and its adoption by practitioners and communities implementing transformative change processes. Despite this complexity of opinion, the following sections discuss key themes related to the grounding and defining of transformation in ocean governance.

Examining buzzwords

Eight interviewees labelled transformation as a buzzword, often highlighting the term’s popularity and expected short lifespan. Interviewee 15 compared transformation to biodiversity, stating “It's almost like the word biodiversity… it's become overused to the point that it's lost its meaning.” Scepticism and fear that transformation is (or could be) a buzzword were reflected across a breadth of interviewee demographics.

Buzzwords, defined as “a word or phrase, are often an item of jargon that is fashionable at a particular time or in a particular context”, have significant power and utility in catalysing conversation but are less impactful in driving tangible change (“Buzzword”, Oxford English Dictionary 2023). As noted by Rist (2007) and Cairns and Krzywoszynska (2016), buzzwords tend to have no real definition but “a strong belief in what the notion is supposed to bring about” (Rist 2007, p. 487). The plurality of ideas about what does or does not constitute transformation in the context of ocean governance throughout these interviews confirms this lack of definition. In addition, ideas about what transformation is intended to achieve were also conflicting or diverging, evidenced by the different depths and processes of transformation outlined in “Defining radical and incremental” section.

The ability of buzzwords to capture and shape zeitgeist warrants deeper exploration, especially when advocating for radical change which to some extent is also becoming a buzzword. An example of this is the sense that transformation is a newer term used to describe older or existing processes of change. As reflected by Interviewee 22, a scientist working at the policy interface, “I wouldn't say transformative change is actually that new, it’s just that it's a new word for it.” The sentiment that transformation is a new way of describing old processes and thought patterns was identified by seven interviewees and re-enforces the classification of transformation as a buzzword. “[calls for transformation are] not new. The problems aren't new either. The same old problems.” (Interviewee 15). This acknowledgement that transformation reinforced repeating thought patterns highlighted a sense of distrust amongst some interviewees.

Interviewee 23 summarised this distrust as “[it sounds like] a term that someone came up with to make sure it gets attention and probably fits with the zeitgeist, but it'll get funding… but it's describing something that's probably already in play.” This leads to questions about the temporality of transformation and the difficulties of identifying and sustaining the ‘buzz’ around transformation. For example, an interviewee in the UK reflected on the transformation that was the implementation of the Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009), through its facilitation towards a more joined-up approach to coastal governance in England and Wales and the creation of the Marine Management Organisation. In their experience, transformations are often long-term processes that can lose buy-in or allure and be rushed or unfinished because of new ‘buzzword’ topics that change the trajectories of existing action. The Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009) was identified as a transformation “which we are still in the middle of” (Interviewee 23).

A further risk of buzzwords is that they can “shelter multiple agendas” across policy, negotiation spaces, and implementation processes (Cornwall 2007, p. 474), which was explicitly identified by Interviewee 11 and discussed through the concept of greenwashing by others. Interviewee 11 noted that “…it risks being co-opted to promote all kinds of different agendas […] some of the agendas that are being called transformative are very much business as usual, exploitive of the environment, exploitive of social communities continue accumulation of wealth and power amongst a small few”. The risk of greenwashing, summarised here as false advertising, was noted by five interviewees highlighting serious concerns surrounding how genuine transformation in ocean systems can be achieved, and what the goal of transformation should be. It is unclear how greenwashing can be completely mitigated in transformation, which goal of transformation is inherently ‘good’ or right, or how it can be assured that the result of transformation is not “business as usual” (Interviewee 20) (Blythe et al. 2018).

In summary, transformation in the view of interviewees was firmly considered to be a buzzword. However, simply categorising transformation as “… just a buzzword, we're obsessed with buzzwords. It's just a sexy buzzword” (Interviewee 23) risks diminishing the power of the concept, and neglects the power of buzzwords to inspire change. The unique ability of buzzwords to capture a zeitgeist or underlying social demand is critical to the success of transformations. Within the global context of calls for transformation within ocean governance, this power is needed to incite change across the ocean governance system.

A plurality of definitions

It is clear in the academic literature that transformation means different things in different contexts (O’Brien 2012; Nalau and Handmer 2015). Most interviewees began with a standard dictionary-type definition of transformation, and then through discussion and examples formulated a different definition with more nuance. For example, Interviewee 10 initially advocated for “the dictionary says it's to change from one state to another, right? I mean so let's keep with that, let's not turn it into some policy speak.” However, by the end of the interview, Interviewee 10 had refined their idea to one that conceptualised transformation as a continuum; incorporating both incremental linear change and more radical transformative changes. It was difficult to identify patterns and themes for any demographic with there being widespread views within demographic categories. Defining transformation was often not simple for interviewees and involved reflection on previous discussions throughout the interview.

When asked to define transformation, and in resultant discussions, interviewees were often aware of their definition’s tractability and distance from reality. Ensuring that the concept was grounded in ‘what actually happens’ seemed a key priority, with five interviewees identifying the need for definitions to not be limited to academic constructs. Interviewee 2 noted the need to remain aware of “what is an academic construct and what is real” when discussing the characteristics of transformation. The anticipated and observed disconnect between examples of transformation given by practitioners versus academics was unsurprising. When questioned about how they would define transformation, Interviewee 2 remarked “What I find interesting is that you can have theoretical debates about what a word means—the reality is what people on the ground think it means.” From several non-academic interviewees, there was a definite sense that the academic conceptualisation of transformation is “fairly remote from reality” (Interviewee 8). However, non-academic definitions in this context were not uniform. For example, when reflecting on the UK government-level interpretation of transformation, Interviewee 2, a previous UK government employee stated “When you go into a government and you say ‘I've got a transformation plan for you’ it only means one thing- that that means radical, fast, change and I haven't met anybody who works in government who doesn't think that.” This interpretation of transformation was not shared across government-related interviewees and is indicative of a lack of shared understanding even amongst interviewees with shared professional experience.

Despite initial assertions that transformation is a fundamental and widespread change, interviewees often through examples identified the need for more context-specific definitions. This approach has been de facto adopted in the context of the blue economy, where several interpretations of the same concept are used across different scales and contexts. The breadth of interpretations of the blue economy is well identified (Silver et al. 2015; Voyer et al. 2018), and are contrastingly often presented as a limitation of the concept. A major limitation often stems from a lack of standardisation prohibiting movement towards the same goal (McKinley 2022). However, it now seems standard practice to justify and parameterise the definition from different viewpoints. A possible avenue for transformative ocean governance is to adopt a similar approach which relies on a context-specific approach, such as a national interpretation.

Defining radical and incremental

Discussion of transformations in academic literature often incorporate critiques of incremental and radical change (Brand 2016; Termeer et al. 2017), which are defined in different ways across different disciplinary understandings of transformation. For example, incremental change can be defined as a small change in depth (shallow), speed (slow), or as a form of change which relies on current modes of thought (Termeer et al. 2017). It can be defined as either one of these characteristics or a combination of the three resulting in the need to be explicit and specific when discussing. In short, shared understandings of incremental and radical cannot be assumed. The use of radical versus incremental change plays a contested role in transformation and was a key part of interviewee discussion and forms the basis of the following sub-sections.

Generally, views regarding incremental and radical change were mixed and non-exclusive; generally favouring incremental change did not preclude the interviewee from appreciating the flaws with it, or completely disregarding the need for radical change. However, several interviewees favoured one approach over the other. 17 interviewees identified the general need for radical change, 15 identified the need for incremental change, with 11 identifying the need for both.

Incremental change

Incremental change was characterised in many different ways, ranging from small, slow, and shallow changes that continue along a linear pathway of change to those that are essentially smaller, deeper and more radical transformations. In general, incremental change was seen as more process-led: “It's going from a stage one to stage two… it's not business as usual, you know, that doesn't mean that you don't need to take small steps to get to the type of change that you actually aspire to” (Interviewee 21). Incremental change was viewed as being similar to transition, a concept that has been explored in the context of ocean governance (Rudolph et al. 2020). In support of an incremental or ‘evolutionary’ approach, Interviewee 23 stated that it was “oftentimes it's evolution, not revolution…” that facilitated transformative change. They further went on to clarify that evolutionary change does not preclude radical action, and can be just as transformative as larger, radical changes and was often the process by which transformation is achieved in a governance sphere.

Two interviewees discussed the potential for intentional small-scale experimentation as part of an incremental approach and described in detail how these nurtured experiments could facilitate transformation. There was little consensus as to what exactly incremental change entailed, or how it could be parameterised and recognised in practice. An example given by Interviewee 10 of transformative incremental change was the 30 × 30 initiative led by the Global Ocean Alliance, which seeks to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030 (DEFRA 2020). Interestingly, other interviewees felt that 30 × 30 is non-transformative, and identified the danger of conflating progress with transformation. Interviewee 10 stated “It's incremental change… 30 by 30 would have been inconceivable 12 years ago when we were just negotiating a 10% [increase in protected areas…] That's not transformative in my mind, that's incremental, right? It's a big job. 10 to 30 is a big jump, but it's still just sort of more of the same right? So maybe I'm being a harsher critic. Some people would call 30 by 30 transformative. I'm not sure it is, but it's definitely a big improvement”.

To some extent, it was felt that incremental change was already happening, but “just isn’t enough” (Interviewee 19) to achieve the scale and depth of change required. There was trepidation that incremental change is “… not very encouraging and so more the same, or little tiny improvements over the long term, is not going to do it. It's just not going to happen.” (Interviewee 3). A similar perception is held in academic literature that incremental change is not enough to facilitate transformation (Rudolph et al. 2020; Blythe et al. 2021b), as it could not garner the momentum or pace required to change the entrenched practices that perpetuate the current system.

In contrast, Interviewee 12 commented on how external agencies in the Pacific exploring how to facilitate 30 × 30 is causing reflection into on the alignment and effectiveness of existing initiatives. In this regard, while not typically identified as a transformative process, the actions taken to align already existing measures under the auspices of an agreed target represent a form of procedural transformation. In addition, this augments the view that transformational action can feel and be incremental at the time of occurrence, and only with hindsight will it actually be deemed transformative.

Radical change

A range of different interpretations of ‘radical’ exist in the literature, such as “top-down and episodic change” (Termeer and Metze 2019, p. 3), and targeting the “roots” of persistent problems (Temper et al. 2018, p. 751). Despite 17 interviewees identifying the need for radical change, interviewees found it difficult to fully define radical. To some extent, radical can also be considered a buzzword, as it was often used by interviewees with assumed mutual understanding. Radical change, in contrast to incremental change, was seen as a more “superhero” type change: “It's a little bit… exciting and miraculous and we've transformed, you know, we've really managed to change something. We haven't tweaked it. We haven't adapted it. We've actually leaped into it in a new state” (Interviewee 5).

When pressed for a definition, interviewees often used terminology like ‘a fundamental shakeup’ or ‘revolution’. There was often an element of “something more”, like “magic” or more a “superhero” like quality which distinguished radical actions to other types of changes. Beyond these nebulous assertions that radical change is needed, there was limited tangibility to the term as what qualifies as radical is inherently subjective (Fazey et al. 2018).

Numerous limitations to radical transformation were identified by interviewees, including disbelief that radical change could happen, how alienating calling for radical change can be to stakeholders, and the limited practical applicability of radical change. Interviewees highlighted disbelief in the ability to undertake radical change related to many identified barriers raging from structural (such as existing decision-making processes), social (such as the belief that humans are fundamentally not good at transformation), and a strong belief that ‘nothing actually happens’. These barriers to radical change represent a significant practical challenge and led some interviewees to conclude that transformational change would be fixing the persistent challenges in ocean governance. This is similar to the approach of Kelly et al. (2018, 2019), who position transformative change in the context of national marine management as fixing persistent problems in governance.

Interviewee 7 highlighted this disbelief in the context of radical change:

Interviewee 7: …so for me, the transformation is a significant shift in that trajectory. For me, that's a bit more accessible than saying […] What was the phrase again?

Interviewer: Radical and nonlinear?

Interviewee 7: Oh, just get over yourselves! *Laughter*

The gap between perceived academic ideas of radical change and practical applications of the concept was highlighted by six interviewees, from a range of professional backgrounds. This is a major limitation to the deployment of radical transformation. Interviewee 21 acknowledged that in reality, “even though I would like it to be radical and fairly immediate, I know that it only will happen through incremental change.” This highlights a need to look at the intersection of incremental and radical change. 11 interviewees mentioned that elements of radical and incremental changes are required to achieve systems change. Several interviewees questioned the “forced dichotomy” of regarding incremental and radical as opposing narratives. Ultimately, it was felt by some that “drawing distinction being radical and incremental creates… [it] makes it seem further apart than it is […] some change is slow, some change is rapid, but all change is incremental because you've gone from A to B” (Interviewee 7). Interviewee 22 stated “we do need radical change, but I think it has to be incremental and I don't see them as exclusive”.

In addition to these vague and ephemeral qualities, a sense of distrust was also observed amongst some interviewees linked to the concept of radicalism. This was also grounded in fear to some extent—“If they saw true transformation, I don’t think they’d like what they saw.” (Interviewee 10). The idea of a ‘sanitised’ form of transformation which has social or policy buy-in, was discussed implicitly across several interviewees, with the implication of there being a threshold at which transformation is viable. However, given the subjective nature of the definitions of radical provided, it is difficult to determine any consensus as to what exactly constitutes radical.

Using both radical and incremental

In summary, interviewees had complex understandings of transformation through both incremental and radical lenses. What emerged from these differences, however, was the clear understanding that transformative change does not axiomatically preclude incremental change. Eleven interviewees identified the need for a mix of both incremental and radical transformation across the ocean governance system. Interviewee 21 summarised this relationship as “when I put my hat as a practitioner, I know that the reality is…. that's why I say it's aspirational, because even though I would like it to be radical and fairly immediate, I know that it only will happen through incremental change.” In general, despite the acknowledgement that both types of change are required, there was limited understanding of how they can be used together, an idea explored in more depth in “Radical and incremental: transformation in ocean governance” section. The deeper and practically grounded understandings of radical and incremental change explored throughout “Defining and grounding transformation in expert perspectives” section illustrate the range of actions that can be employed in pursuit of ocean governance transformations.

Leverage points

General findings

The top three leverage points identified were changing ways of working (18), decision-making processes (16), and developing support for change (15) (Table 1, Fig. 2). Fewer interviewees identified leverage points like system design, power, and technological solutions (4). Illustrative quotes that highlight the diversity of codes that created each category of leverage are given in Table 2. It is tempting to suggest that none of these categories of leverage are particularly radical, and when disaggregated down to the individual leverage point, none are completely novel. For example, ‘changing ways of working’ incorporates many points of intervention (identified as leverage points) such as “breaking silos”, “fostering collaboration” and “valuing different perspectives”. These are ideas and concepts that have been debated and advocated in marine and ocean governance for decades through integrated ocean management and marine spatial planning. However, it is evident that practitioners feel that these are past ideas of change that have not yet materialised or ‘gone far enough’ in achieving change. This adds weight to the perception that transformation is just “doing what we said we were going to do 40 years ago” (Interviewee 7).

The key observation is that the most commonly stated response in interviews (beyond a few truly innovative or “pie in the sky” visions of change) were things already known to us, representing a potential implementation gap in the ideas that transformation conjures and its practical realisation. For example, in Table 2 under ‘changing ways of working’, Interviewee 1 outlines the need for more inclusive, multi-stakeholder ways of working, which is a concept that has been advocated for in marine planning and governance for at least a decade (Fletcher et al. 2013). This implementation gap represents a serious concern and barrier to communication between academics theorising transformation, and those charged with its actual implementation. This disconnect exacerbates the contrasting interpretations of radical change given in “Radical change” section, such as transformation being a fundamental and complete reworking of the governance system, and contributes to the overall subjectivity of the concept. In short, this represents a major challenge to ensuring accountability and legitimacy of transformative action as different interventions are pursued in pursuit of transformation.

The limited of discussion of power is particularly concerning given the centrality of power within academic discussions of transformation, widening the disconnect between theory and practice (Blythe et al. 2023; Chuenpagdee et al. 2022). Re-evaluating and changing power structures is regarded as a central element of ocean governance transformations within academic literature, representing a disconnect between theory and practice (Blythe et al. 2018; Bennett et al. 2019). The aggregated codes ‘changing ways of working’ and ‘decision making processes’ address some elements of increased equity and inclusivity within how people are structurally organised in ocean governance systems, but the explicit discussion of power was largely missing from the majority of interviews.

The ‘puzzle’ of leverage points

In total, 16 interviewees advocated for a multi-leverage point approach, whereby “…with a kind of realpolitik sense…you need to follow a whole stream of approaches” (Interviewee 20). The belief was largely shared that “if you're going for transformation then you want every angle possible” (Interviewee 3). Thus, it is clear that interviewees felt that a multi-leverage approach is required, necessitating action across the breadth of depth of leverage points identified. In this regard, leverage points can be conceptualised as a puzzle, in which different depths of leverage can be activated across the wider system to facilitate transformative change (Bolton 2022).

The resultant ‘puzzle’ (Fig. 2) of leverage points paints a complex picture of interdependencies, supporting and facilitating interventions that are difficult to untangle. For example, interviewees often noted that a change in law would require a significant change in government working patterns to allow for implementation. Leverage points were sorted into multiple categories where needed. For example, law was discussed as both a structural and mechanistic leverage point (e.g., ‘creating new legislation’, sorted into design) and as a regulatory parameter.

In general, interviewees identified a range of differing depths of leverage points, as depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Depth of leverage points identified ranged from relatively shallow interventions, such as developing new technological solutions to social and environmental issues, to questioning and redefining the fundamental values, goals, and assumptions that the ocean governance system is built on (Fig. 2 and Table 1). No particular depth of leverage had significantly more discussion than any other, and interviewees tended to identify a range of leverage points rather than focus on one particular depth or intervention. This indicates that while potentially not a conscious decision of interviewees, there is a strong recognition of the need for intervention at all depths of leverage. The diversity of examples given further consolidates the finding that transformation is perceived as requiring “all parts of the puzzle” (Interviewee 6).

Disconnects between theory and practice

Throughout analysis, two key disconnects between practice and theory were identified. Firstly, a diverse list of interventions were generated by interviewees that were grouped and abstracted into categories of leverage points, as discussed in “Methods” section. Sorting and categorising the leverage points generated through this research was challenging, as leverage points could often fit into multiple categories. For example, the following quote was coded and categorised in different ways:

“we need to be building those experiences of multiple stakeholders in the room sharing information, building the trust, understanding the common threats and building the common interests” (Interviewee 1)

This leverage point was classified into both ‘changing ways of working’ and ‘decision making processes’ as it references both the behavioural and people-centric classification of changing ways of working, and the more structural category ‘decision-making processes’. Further difficulties arise when attempting to fit the list of categories of leverage points to Abson’s et al. (2017) hierarchy of leverage (Table 1, Fig. 2). Significant overlaps and synergies were identified between the interventions discussed and the different classifications of leverage points they were sorted into. Most of the leverage points identified by interviewees could be translated into Abson et al. (2017) framework, but some, such as knowledge and learning, were discussed more in the context of underlying areas that could enable transformative processes to occur. While these leverage points could be considered to form part of the ‘design’ category of leverage [which is defined as “the social structures and institutions that manage feedbacks and parameters” (Abson et al. 2017, p. 32)], the ubiquity of the interventions led to the creation of a separate classification. The difficulty in translating expert ideas of leverage into academic theorisations and classifications is indicative of a deeper disconnect in both the language and practice of systems change between academia and those implementing change. As identified above, what practitioners understand as a leverage point does not easily translate into academic theories.

Secondly, differences in the understandings of what leverage points are were identified, despite measures outlined in the introduction. When discussing leverage points, or identifying leverage points in practice, it was clear that the distinction between an intervention and a leverage point was often not clear. It was noted that there was a distinct lack of guidance in published literature regarding identifying leverage points, beyond the existence of classifications of leverage (Murphy 2022), representing a significant need for further study.

This disconnect was further evidenced by the caveats used when interviewees began discussing the concept of leverage. When asked what leverage points could be used to transform ocean governance, three interviewees immediately caveated the approach by stating that leverage points are not silver bullets for transformation (Interviewee 9, Interviewee 16, Interviewee 13). The concept of a silver bullet is part of the “lore” of leverage points (Meadows 2009, p. 145), and perpetuates the idea that there is a single solution to major crises. While this interpretation of leverage is not advocated for in literature, reference to its prevalence within the systems practice community is made by Birney (2021, p. 761): “this is often the mistake we make: we are hoping that if we look at an analysis long enough it will give us the silver bullet to change the system”. Given the early rejection of by many interviewees of such a narrative of leverage points, it is clear that this is a misconception which translates into practice and represents a disconnect between theory and practice.

Radical and incremental: transformation in ocean governance

Transformation as a solution to ocean governance crises faces a pragmatic challenge: it must be concurrently grounded in realism and achieving the ‘superhero’ impossible. The conceptualisation of transformation and the findings from these interviews represents an understanding of transformation in ocean governance that is one of complexity that rejects the notion of a forced dichotomous relationship between incremental and radical change and instead recognises the potential complementary approaches of both. By coupling the findings of “Defining and grounding transformation in expert perspectives” and “Leverage points” sections, it is clear that transformation in ocean governance must be achieved through both incremental and radical approaches, using a multi-leverage point approach across different depths of change. While interpretations of incremental and radical differed throughout the interviews, here the general understanding of incremental being smaller, stepwise change and radical being more fundamental and therefore disruptive change is adopted. When aligning this interpretation with leverage points, it is logical to equate shallower leverage points with incremental change, and deeper leverage points to create radical change. Literature to date focuses on the use or advocation of deeper leverage points to create transformation, rather than mixes of leverage points (Woiwode et al. 2021; Davelaar 2021; Dorninger et al. 2020). The findings of this research instead encourage the exploration of both shallow and deep leverage points in succession or potentially concurrently. Finally, it is clear that from a practitioner perspective, interventions to create change will largely be actions that are already ‘known’ to us, rather than ‘pie in the sky’, new ideas. The remainder of this section explores this proposed model of change, and how this conceptualisation relates to academic literature.

Literature tends to advocate for either incrementalism or radical change, with notable examples outlined throughout the rest of this discussion (Evans et al. 2023). The idea of using both radical and incremental change is not new but is not the dominant discourse in academia which suggests a further disconnect between what practitioners envision and enact as transformative change, and what academics theorise. Patterson et al. (2017, p. 4) proposed that governance for transformations sees the interdependency of incremental and radical change as “an honest recognition” of the practical need for near-term incrementalism “with a transformative agenda”. In ocean governance transformation literature, the approach advocated for here is novel.

When comparing the finding of both radical and incremental change to facilitate transformation to existing models and ideas of change, two areas of models of change emerge: transition theory and small-wins. The idea of using both radical and incremental changes draw parallels to niche innovation which forms part of transition theory, whereby small innovations at local levels can grow to catalyse to wider transformation (Rudolph et al. 2020). In contrast to the observation of Temper et al. (2018, p. 748), who identify the relationship between transition (or incremental change) and transformation as being “two competing or at best complementary approaches”, the intersection of transformative (radical) and transition (incremental) approaches was identified by interviewees as being what should happen in practice (Hölscher et al. 2018). The tension identified by Temper et al. (2018) stems from the conceptualisation of transformation being unable to be “ordered, managed, controlled…(emerging) from unruly political alliances, diverse knowledges and collective organisation” (Scoones 2016, p. 310). This was not a sentiment echoed by interviewees, beyond two interviewees identifying the “magic” and “superhero” qualities of radical change in contrast to incremental change. Again, rejecting this dualistic perception of transformation as ‘either-or’ incremental and radical change could allow for the emergence of ‘small wins’ which creates a more tangible process through which to achieve transformation.

The concept of continuous change also parallels the findings of this research, which has been explored from a climate governance perspective by Termeer et al. (2017). Scoones et al. (2015) explore the idea of aggregatory incremental change from a political ecology perspective. Similar models have been explored from a governance perspective, most notably ‘small wins’ (Termeer et al. 2017) and ‘niche change’ (Westley et al. 2011). The idea that small wins can amplify into larger systems change is also similar to the idea of niche-level change in transition theory (Monkelbaan 2019), which has begun to be explored in the context of ocean governance transformation (Rudolph et al. 2020). The concept of ‘small wins’ within transformative literature parallels the type of change described in this paper, especially in the context of continuous change (Termeer and Metze 2019; Woiwode et al. 2021). Small wins are defined as “initiatives showing concrete in-depth change” (Woiwode et al. 2021) or “radical steps of moderate importance” (Weick 1984, as quoted in Termeer and Metze 2019, p. 3). Small wins, which are similar to incremental change, can be diverse in scope, such as innovation, experimentation, institutionalisation of innovation, and their small size makes them unthreatening to actors within the system (Termeer and Metze 2019).

Incremental change can also be achieved by niche-level innovation to lead to transformation in complex systems such as ocean governance has been explored by Rudolph et al. (2020). Niche innovation in this context can be “technical, cultural, social, economic, political or legal” and are characterised as being incremental, pragmatic and learning-focused (Lubchenco et al. 2016; Rudolph et al. 2020, p. 7). Rudolph et al. (2020) identify several niche-level innovations (such as rights based fisheries management and legal innovations) that have capacity to transform ocean governance, but it remains unclear how niche changes are identified in situ.

While interviewees have advocated for transformation that uses both incremental and radical approaches for ocean governance transformations, literature largely conceptualises them both as separate. However, it is suggested that there is a gradient between the two types of change, and that they are not mutually exclusive. The relationship, delimitations between and intersections of radical and incremental change are less understood. Interviewees held a range of beliefs: incremental change leads to radical change, the two are mutually exclusive, the two are inseparable, or the two are just change at different scales. Interviewees were clear that both types of change are needed. This gradient could be dependent on scale, speed and scope of change (Fazey et al. 2018). For example, radical change can also be smaller in scale or localised in its impact, or slower in its deployment. On the other hand, incremental change can radical in character, or rapid in its deployment. Future work could explore this proposed gradient of incremental–radical change and explore its utility in the context of ocean governance transformations.

In summary, the model of change drawn from collective interviews has some traction in existing literature. However, it contrasts strongly with the characterisation of transformation as being either radical or incremental, which is the dominant perspective in literature. Such a conceptualisation represents a major gap between what academics theorise, and what practitioners envision and enact in pursuit of transformative change. While logically, the idea of using incremental and radical changes across various leverage points of varying depths makes sense, it is unclear how these would work in practice or how such an approach could be achieved. A significant gap in ocean governance transformations literature regarding leverage points also confirms that this is a significant area of future study given the transformative turn of global policy to date.

Conclusions

Transformation in ocean governance is a concept that is progressively presented as the solution to the multitude of crises, issues and challenges facing oceanic environments, such as pollution, biodiversity loss and the effects of climate change. While interpretations of transformation exist in academic literature, this research has sought to provide a ground-truthed interpretation of what transformation is and begun to explore how it can be achieved in ocean governance through a leverage points perspective. From 24 interviews with experts and practitioners of ocean governance across a range of perspectives, it is clear that transformation is a complex and multifaceted topic, demonstrating the challenges of presenting a unified view of the subject. While perceptions of the concept ranged from apparent contempt to excitement, it was largely felt that transformation was needed in ocean governance, despite its buzzword status. It was largely agreed that transformation in the context of ocean governance should reject the perceived forced binary of incremental versus radical change, and instead employ both concurrently to achieve change, using a breadth of leverage points across differing depths. In short, it must reject the idea of a single solution and instead embrace the plurality and complexity of change.

Significant work remains regarding exploring specific leverage points in ocean governance. This research has begun to discuss how leverage points are understood by practitioners of ocean governance, and proposed a ‘puzzle’ led approach which emphasises the interdependencies of leverage points. Critically, it is evident that there is a major gap in the understanding of what transformation is and how it is achieved, between academics and practitioners. This is evident in both the scale of intervention envisioned, such as “pie in the sky” transformation versus “things that we said we’d do 40 years ago”, and in the discussion of leverage points, where deep change is advocated for in literature, but a plural approach using multiple depths favoured in practice. This will require current approaches to ocean governance, such as marine spatial planning and integrated coastal management, to be re-evaluated to identify how a more nuanced understanding of transformation can contribute to addressing the critical governance issues facing the ocean.

References

Abson DJ et al (2017) Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46(1):30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Bennett NJ et al (2019) Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability (switzerland) 11(14):1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143881

Birney A (2021) How do we know where there is potential to intervene and leverage impact in a changing system? The practitioners perspective. Sustain Sci 16(3):749–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00956-5

Blythe J et al (2018) The dark side of transformation: latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode 50(5):1206–1223. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12405

Blythe J, Armitage D et al (2021a) Conditions and cautions for transforming ocean governance. In: Baird J, Plummer R (eds) Water resilience. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 241–261

Blythe J, Bennett NJ et al (2021b) The politics of ocean governance transformations. Front Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.634718

Blythe JL et al (2023) Blue justice: a review of emerging scholarship and resistance movements. Camb Prisms Coast Futures 1:e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.4

Boik JC (2020) Science-driven societal transformation, part i: worldview. Sustainability (switzerland) 12(17):1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12176881

Bolton M (2022) A system leverage points approach to governance for sustainable development. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01188-x

Brand U (2016) “Transformation” as a new critical orthodoxy: the strategic use of the term “transformation” does not prevent multiple crises. Gaia 25(1):23–27. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.25.1.7

Bulkeley H, Kok M, van Dijk JJ, Forsyth T, Nagy G, Villasante S (2020) Moving towards transformative change for biodiversity: harnessing the potential of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. UK Centre for ecology & hydrology, An EKLIPSE expert working group report

Buzzword (2023) Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=buzzword. Accessed 31 Aug 2023

Cairns R, Krzywoszynska A (2016) Anatomy of a buzzword: the emergence of “the water-energy-food nexus” in UK natural resource debates. Environ Sci Policy 64:164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.07.007

Campbell LM et al (2016) Global oceans governance: new and emerging issues. Annu Rev Environ Resour 41:517–543. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021121

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Reprinted 2009. Los Angeles London, SAGE. https://umich.instructure.com/courses/122789/files/4115070/download?verifier=ywZvEyi7E1laJkBqoS4fjN4r0OWijLJgRGVPSfQl&wrap=1. Accessed 27 Aug 2023

Chuenpagdee R et al (2022) Collective experiences, lessons, and reflections about blue justice. In: Jentoft S et al (eds) Blue justice. MARE publication series. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 657–680

Cisneros-Montemayor AM et al (2019) Social equity and benefits as the nexus of a transformative Blue Economy: a sectoral review of implications. Mar Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103702

Cornwall A (2007) Buzzwords and fuzzwords: deconstructing development discourse. Dev Practice 17(4–5):471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469302

Dauvergne P (2018) Why is the global governance of plastic failing the oceans? Glob Environ Change 51:22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.05.002

Davelaar D (2021) Transformation for sustainability: a deep leverage points approach. Sustain Sci 16(3):727–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00872-0

Denscombe M (2010) The good research guide: for small-scale social research projects, 4th edn. Open University Press, McGraw Publishers, England

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2020) Global ocean alliance: 30 countries are now calling for greater ocean protection, GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/global-ocean-alliance-30-countries-are-now-calling-for-greater-ocean-protection. Accessed 26 January 2023

Dorninger C et al (2020) Leverage points for sustainability transformation: a review on interventions in food and energy systems. Ecol Econ 171:106570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106570

Erinosho B et al (2021) Transformative governance for ocean biodiversity. In: Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Kok M (eds) Transforming biodiversity governance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Evans T et al (2023) Untangling theories of transformation: reflections for ocean governance. Mar Policy 155:105710

Fazey I et al (2018) Transformation in a changing climate: a research agenda. Clim Dev 10(3):197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1301864

Fischer J, Riechers M (2019) A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat 1(1):115–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.13

Fletcher S, McKinley E, Buchan KC, Smith N, McHugh K (2013) Effective practice in marine spatial planning: a participatory evaluation of experience in Southern England. Mar Policy 39:341–348

Gelcich S et al (2010) Navigating transformations in governance of Chilean marine coastal resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(39):16794–16799. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012021107

Gelcich S, Reyes-Mendy F, Rios MA (2019) Early assessments of marine governance transformations: Insights and recommendations for implementing new fisheries management regimes. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10517-240112

Gerhardinger LC et al (2020) Crafting a sustainability transition experiment for the Brazilian blue economy. Mar Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104157

Hardoš P (2018) Who exactly is an expert? On the problem of defining and recognizing expertise. Slovak Sociol Rev 50(3):268–288

Heinze C et al (2021) The quiet crossing of ocean tipping points. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(9):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008478118

High Level Ocean Panel (2020) Transformations for a sustainable ocean economy: a vision for protection, production and prosperity. High Level Ocean Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy

Hölscher K, Wittmayer JM, Loorbach D (2018) Transition versus transformation: what’s the difference? Environ Innov Soc Transit 27:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019) In: Pörtner H-O et al. (eds) IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. IPCC

Kelly C, Ellis G, Flannery W (2018) Conceptualising change in marine governance: learning from transition management. Mar Policy 95:24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.023

Kelly C, Ellis G, Flannery W (2019) Unravelling persistent problems to transformative marine governance. Front Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00213

Leventon J, Abson DJ, Lang DJ (2021) Leverage points for sustainability transformations: nine guiding questions for sustainability science and practice. Sustain Sci 16(3):721–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00961-8

Linnér BO, Wibeck V (2021) Drivers of sustainability transformations: leverage points, contexts and conjunctures. Sustain Sci 16(3):889–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00957-4

Lubchenco J et al (2016) The right incentives enable ocean sustainability successes and provide hope for the future. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(51):14507–14514. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604982113

McKinley E (2022) A blue economy for whom? In: Morrissey JE, Heidkamp CP, Duret CG (eds) Blue economy, 1st edn. Routledge, London, pp 13–25

McKinley E, Ballinger RC (2018) Welsh legislation in a new era: a stakeholder perspective for coastal management. Mar Policy 97:253–261

Meadows D (1999) Leverage points places to intervene in a system. Sustainability Institute, North Charleston

Meadows D (2009) Thinking in systems: a primer. Earthscan, London

Monkelbaan J (2019) Governance for the sustainable development goals: exploring an integrative framework of theories, tools, and competencies. Springer, Singapore

Murphy R (2022) Finding (a theory of) leverage for systemic change: a systemic design research agenda. Contexts Syst Des J. https://doi.org/10.58279/v1004

Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaie F (2017) Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev Med Educ 14(3):e67670

Nalau J, Handmer J (2015) When is transformation a viable policy alternative? Environ Sci Policy 54:349–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.022

O’Brien K (2012) Global environmental change II: from adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progr Hum Geogr 36(5):667–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511425767

O’Brien K (2018) Is the 1.5°C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 31:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.04.010

Patterson J et al (2017) Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ Innov Soc Transit 24:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001

Pickering J et al (2022) Rethinking and upholding justice and equity in transformative biodiversity governance. In: Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Kok MTJ (eds) Transforming biodiversity governance. Cambridge University Press, UK

Riechers M, Loos J et al (2021a) Key advantages of the leverage points perspective to shape human–nature relations. Ecosyst People 17(1):205–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2021.1912829

Riechers M, Brunner BP et al (2021b) Leverage points for addressing marine and coastal pollution: a review. Mar Pollut Bull 167:112263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112263

Rist G (2007) Development as a buzzword. Dev Practice 17(4–5):485–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469328

Rudolph TB et al (2020) A transition to sustainable ocean governance. Nat Commun 11(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17410-2

Saldaña J (2021) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 4th edn. SAGE Publications Ltd, New York

Scoones I (2016) The politics of sustainability and development. Annu Rev Environ Resour 41(1):293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090039

Scoones I, Leach M, Newell P (2015) The politics of green transformations. Routledge, London

Silver JJ et al (2015) Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. J Environ Dev 24(2):135–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496515580797

Temper L et al (2018) A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: resistances, movements, alternatives. Sustain Sci 13:747–746

Termeer CJAM, Metze TAP (2019) More than peanuts: transformation towards a circular economy through a small-wins governance framework. J Clean Prod 240:118272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118272

Termeer CJAM, Dewulf A, Biesbroek GR (2017) Transformational change: governance interventions for climate change adaptation from a continuous change perspective. J Environ Plan Manage 60(4):558–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1168288

Virdin J et al (2021) The Ocean 100: transnational corporations in the ocean economy. Sci Adv 7(3):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc8041

Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Kok M (eds) (2022) Transforming biodiversity governance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Voyer M et al (2018) Shades of blue: what do competing interpretations of the blue economy mean for oceans governance? J Environ Policy Plan 20(5):595–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1473153

Weick KE (1984) Small wins: redefining the scale of social problems. Am Psychol 39(1):40e49

Westley F et al (2011) Tipping toward sustainability: emerging pathways of transformation. Ambio 40(7):762–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0186-9

Woiwode C, Schäpke N, Bina O, Veciana S, Kunze I, Parodi O, Schweizer-Ries P, Wamsler C (2021) Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustain Sci 16(3):841–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00882-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. This research was financed by the University of Portsmouth.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by Jerneja Penca, Znanstveno-raziskovalno sredisce Koper, Slovenia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, T., Fletcher, S., Failler, P. et al. Radical and incremental, a multi-leverage point approach to transformation in ocean governance. Sustain Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-024-01507-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-024-01507-4