ASTRACT

BACKGROUND

Despite the identification of transfer of patient responsibility as a Core Entrustable Professional Activity for Entering Residency, rigorous methods to evaluate incoming residents’ ability to give a verbal handoff of multiple patients are lacking.

AIM

Our purpose was to implement a multi-patient, simulation-based curriculum to assess verbal handoff performance.

SETTING

Graduate Medical Education (GME) orientation at an urban, academic medical center.

PARTICIPANTS

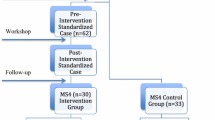

Eighty-four incoming residents from four residency programs participated in the study.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The curriculum featured an online training module and a multi-patient observed simulated handoff experience (M-OSHE). Participants verbally “handed off” three mock patients of varying acuity and were evaluated by a trained “receiver” using an expert-informed, five-item checklist.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Prior handoff experience in medical school was associated with higher checklist scores (23 % none vs. 33 % either third OR fourth year vs. 58 % third AND fourth year, p = 0.021). Prior training was associated with prioritization of patients based on acuity (12 % no training vs. 38 % prior training, p = 0.014). All participants agreed that the M-OSHE realistically portrayed a clinical setting.

CONCLUSIONS

The M-OSHE is a promising strategy for teaching and evaluating entering residents’ ability to give verbal handoffs of multiple patients. Prior training and more handoff experience was associated with higher performance, which suggests that additional handoff training in medical school may be of benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Though essential to quality patient care, handoffs often lack standardization and have been identified as a vulnerable point in care that is susceptible to error.1,2 These errors can result in adverse events, longer hospital-stays, and increased use of medical resources.3–7

In 2011, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) required that all residency programs implement a structured handoff protocol and develop a plan to monitor handoff quality.8,9 More recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) identified handoffs as a Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency (CEPAER) that should be assessed in graduating medical students.10

Because of the variability with which verbal handoff skills are taught and evaluated in medical schools,11 incorporating formal training and assessment during graduate medical education (GME) orientation is an important mechanism to ensure entering residents are competent in performing handoffs. While the I-PASS study has recently demonstrated that the adoption of a handoff bundle by pediatric residents is associated with improved patient outcomes,12 few methods exist to teach and rigorously evaluate the ability of incoming residents to verbally hand off multiple patients.

While simulation has been used to evaluate handoffs during GME orientation,13–15 no one has evaluated the ability of individual trainees to verbally hand off more than one patient in a simulated setting. This is a clear limitation, given that interns transition multiple patients during a handoff. Moreover, due to increasing time constraints in GME orientations nationwide, there is great interest in using web modules, or a “flipped classroom” approach, to facilitate knowledge delivery before interns arrive for orientation. Building on our prior work, we aimed to develop and implement a novel, multi-patient, simulation to assess the ability of incoming residents to give a verbal handoff after they received online training on best handoff practices.16,17

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

The handoff simulation for this study was embedded into a larger GME orientation at a single, urban, academic medical center. As part of a required “Boot-Camp”, 84 interns (Table 1) entering four core residency programs (Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Surgery) rotated through three OSCE-like stations designed to: (1) conduct a verbal handoff (2) acquire informed consent, and (3) break bad news to patients. These were conducted at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Clinical Performance Center. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board deemed this research exempt from review.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Between June 9 and June 20, 2014, interns reviewed an online handoff training module, which summarized previously described curricular content.17 The module was administered by Red Riding Hood© cloud-based survey application created by Click to Play Media™ (Berkeley, CA). The online training consisted of: a 4-min video highlighting handoff pitfalls,17 a 15-min didactic screencast recorded by one of the study investigators (VA), and a seven-question, multiple-choice assessment to ensure knowledge acquisition (See Online Appendix A).

As part of the module, a four-item pre-survey asked trainees whether they had prior handoff training, how much handoff experience they had during medical school (defined as none, during third year only, during fourth year only, during both third and fourth year), and whether they felt prepared to conduct a verbal handoff using a five-point Likert-type scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree (Table 1). A three-item post-survey asked trainees to evaluate the module’s effectiveness, its impact on their future practice, and their preparedness to conduct a handoff.

To assess verbal handoff performance, we developed the modified, Multi-patient Observed Simulated Handoff Experience (M-OSHE), an interactive, handoff simulation that was modeled after our prior single-patient handoff simulation.16,18 Before the simulation, incoming residents were provided with a mock written sign-out created by faculty, which contained clinical information, overnight anticipatory guidance, and tasks requiring follow-up for three patients of varying acuity (See Online Appendix B). Because we focused on assessing verbal handoff ability, we standardized the sign-out form to critically evaluate verbal handoffs. Since a critique of prior handoff simulations was that the sender does not “know” the mock patients, participants were given 48 hours to study the written sign-out to become familiar with the patients.

Equipped with the mock sign-out form, each participant rotated to the handoff case scenario as a part of the larger OSCE, and written door chart directions instructed them to use the information on the sign-out sheet to transfer care of the three patients to one trained receiver during a 15-min time slot (See Online Appendix C). After the encounter, the trained receiver provided the trainee with 5-min of verbal feedback using a five-item checklist developed by the authors. The encounters were digitally recorded via B-Line© via ceiling-mounted cameras in the Clinical Performance Center.

Eleven senior residents and fellows (all of whom had conducted a handoff within the last month) served as standardized “physician-receivers” of the handoff. Prior to the exercise, each physician-receiver reviewed the online module and received training detailing the M-OSHE and their role in evaluating the incoming residents. A five-item checklist developed by the authors was provided to the physician-receivers to assist in their evaluations and feedback (See Online Appendix D).

Envisioned as an easy-to-use tool, the checklist was designed to assess the following five observable behaviors of a successful verbal handoff: prioritization of patients by acuity, communicating in action steps, encouraging questions, providing an appropriate amount of information, and creating a shared communication space. Each behavior was chosen after careful review and deliberation of well-publicized work in this area,16,19–21 previously validated tools to evaluate handoffs such as the Hand-off CEX,22 and the recommendations for handoffs outlined by the Society of Hospital Medicine.23 Four of these behaviors were directly taken from the Handoff CEX. The fifth behavior, creating a shared space, was added after considering recent work by Greenstein, et al. on behaviors that could promote active listening by handoff receivers.21 During their training, the physician-receivers were instructed on what it means to demonstrate the observable behavior versus not demonstrate the behavior, and then to mark whether the skill was done (Yes) or not done (No). For each behavior, a high bar was set for completion. For example, prioritizing patients based on acuity had an exact expected order. All to-do items needed to be included for communicating in action steps. Space was also provided to allow for qualitative comments on participant performance.

Following the M-OSHE, participants completed a six-question evaluation. The questions asked participants to assess the authenticity of the M-OSHE scenario and whether the online module helped prepare them for the M-OSHE, their satisfaction with their performance and with their feedback, whether the curriculum would impact their future practice, and their level of preparedness to conduct a verbal handoff.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all data, including self-reported baseline, post-module, and post M-OSHE preparedness and checklist scores. Interns who rated their preparedness as a “4” or “5” were deemed “prepared.” To test inter-rater reliability, video footage of one-third of the participants was randomly selected, scored by investigators, and compared to the trained-receiver ratings using kappa scores. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05. Concurrent validity was established by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient comparing checklist and validated Handoff mini-CEX scores from trained raters in a subsequent training exercise after M-OSHE. All data analysis was conducted using Stata 13 (College Station, TX).

Eighty-four interns were eligible to participate in this study. All completed the M-OSHE, while 81 (96 %) completed the online module. Although the majority (69 %) had received prior handoff training, only half (28/58, 48 %) of those individuals were satisfied with that training. While most participants (71/84, 85 %) reported some prior handoff experience during medical school, these experiences varied (Table 1). Self-reported preparedness for conducting a verbal handoff increased after the online module (88 % post-module vs. 54 % pre-module, p < 0.0001 Wilcoxon sign-rank test) and after the M-OSHE compared to baseline (70 % post-M-OSHE vs. 54 % pre-module, p < 0.001).

The mean total checklist-score was 3.23 (Range 1–5, S.D. 1.09) and did not differ significantly by residency program (p = 0.60, Kruskal Wallis test). For each behavior evaluated, completion rate ranged from 30 to 96 %, with interns often failing to prioritize patients based on acuity of illness (Table 2). Internal consistency of the checklist was measured at 0.39 with Cronbach-alpha. Inter-rater reliability was moderate to high for four of the observable behaviors on the checklist, with kappa scores ranging from 0.5 to 0.9, while the kappa for the fifth behavior (communicating in action steps) was not calculable due to the very high performance and 96 % inter-rater agreement on this item (Table 2). Performance on the checklist did correlate with Handoff mini-CEX scores, providing evidence for concurrent validity (r = 0.55, p = 0.0001, pwcorr).

Interns who reported more handoff experience during medical school were more likely to complete more than three items on the checklist (p = 0.021, nonparametric test of trend). Prior training was associated with the ability to prioritize patients based on acuity (12 % no training vs. 38 % prior training, p = 0.014, Chi2).

Eighty-one trainees (96 %) completed the post-survey following the online training module and all trainees completed the post-survey following the M-OSHE. Feedback was highly positive. All participants reported the online module was an effective review of handoffs and that the M-OSHE was realistic. Most (88 %) believed the M-OSHE will be useful to their practice as a physician. Interns also expressed positive comments (“Very helpful. I would love to do this again. The more practice we have, the better”). Lastly, 92 % of trainees would recommend this exercise for future incoming residents.

DISCUSSION

While several methods of teaching and evaluating handoffs have been previously described in the literature,16,19,20,24,25 this study is the first to utilize a multi-patient, simulation-based assessment targeting incoming residents. Our results suggest that this may be a promising strategy to provide continuity in handoff training during the transition from undergraduate to graduate medical education and to identify incoming residents in need of additional practice.

These results have important implications for medical educators, given the inclusion of handoffs as a Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency (CEPAER). The superior performance of participants with prior training and more handoff experience underscores the importance of training medical students and providing opportunities to conduct handoffs. A recent literature review regarding handoff education suggests that the inclusion of interactive simulations into handoff curriculum has been more promising than those focused on didactic, online handoff training.13

Performance evaluation based on the checklist highlights room for skill improvement. Despite addressing these topics explicitly in the module, interns struggled with prioritizing patients, creating a shared space, and providing the appropriate amount of information. With baseline performance data, residency programs can identify underperforming residents, tailor on-going training in handoffs, document improvement, and demonstrate achievement of ACGME milestones. In terms of time and resources, this intervention is both practical and achievable for any residency program.

There are several limitations to this innovation. The data collected in this study were derived from a single institution, and only reflect adult-specific handoff scenarios. We are currently developing pediatric cases. Furthermore, data collected regarding prior training and handoff experience was self-reported. Information on the nature of prior training or experience is lacking. We also did not assess ability of entering residents to create a written sign-out, which could be an important supplemental module to build for this simulation. However, interns often use team- or computer-generated sign-out forms that they do not create themselves.26,27 Since our focus was on assessing verbal handoff performance, we believe this simulation is an important tool to assess this competency. We lack data on performance in actual clinical settings. The checklist had a relatively low Cronbach-alpha score, although it was designed to measure distinctly separate domains of a verbal handoff.

The M-OSHE is a promising model for assessing entering residents ability to verbally hand off multiple patients. Embedding this curriculum into GME orientation ensures that all interns receive training before starting practice, provides a baseline assessment of handoff performance, and can identify interns in need of additional training. Future work aims to replicate this assessment at other institutions, develop specialty-specific cases, incorporate remediation and track longitudinal outcomes.

REFERENCES

Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, Wall SD, Wachter RM. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):257–66.

Cohen MD, Hilligoss PB. The published literature on handoffs in hospitals: deficiencies identified in an extensive review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):493–7.

Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–60.

Kitch BT, Cooper JB, Zapol WM, Marder JE, Karson A, Hutter M, et al. Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(10):563–70.

Starmer AJ, Sectish TC, Simon DW, Keohane C, McSweeney ME, Chung EY, et al. Rates of medical errors and preventable adverse events among hospitalized children following implementation of a resident handoff bundle. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(21):2262–70.

Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–7.

Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Rogers SO, Zinner MJ, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533–40.

Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedules to Improve Patient Safety, Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME. Resident duty hours enhancing sleep, supervision, and safety [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009. Accessed Dec 26 2015. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12508

CPRs2013.pdf.

Core EPA Curriculum Dev Guide.pdf.

Liston BW, Tartaglia KM, Evans D, Walker C, Torre D. Handoff practices in undergraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):765–9.

Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, Calaman S, Balmer D, West DC, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):876–84.

DeRienzo CM, Frush K, Barfield ME, Gopwani PR, Griffith BC, Jiang X, et al. Handoffs in the era of duty hours reform: a focused review and strategy to address changes in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Common Program Requirements. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):403–10.

Didwania A, Kriss M, Cohen ER, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB. Internal medicine postgraduate training and assessment of patient handoff skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):394–8.

Allen S, Caton C, Cluver J, Mainous AG, Clyburn B. Targeting improvements in patient safety at a large academic center: an institutional handoff curriculum for graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2014;89(10):1366–9.

Farnan JM, Paro JAM, Rodriguez RM, Reddy ST, Horwitz LI, Johnson JK, et al. Hand-off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand-off experience (OSHE). J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):129–34.

Patient Handoffs: A Typical Day on the Wards [Internet]. 2010. Accessed Dec 26 2015. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzCdoQEYHkY&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Newble D. Techniques for measuring clinical competence: objective structured clinical examinations. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):199–203.

Horwitz LI, Moin T, Green ML. Development and implementation of an oral sign-out skills curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1470–4.

Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, Allen AD, Landrigan CP, Sectish TC. I-PASS, a Mnemonic to Standardize Verbal Handoffs. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):201–4.

Greenstein EA, Arora VM, Staisiunas PG, Banerjee SS, Farnan JM. Characterising physician listening behaviour during hospitalist handoffs using the HEAR checklist. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(3):203–9.

Horwitz LI, Rand D, Staisiunas P, Van Ness PH, Araujo KLB, Banerjee SS, et al. Development of a handoff evaluation tool for shift-to-shift physician handoffs: the Handoff CEX. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):191–200.

Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–40.

Chu ES, Reid M, Schulz T, Burden M, Mancini D, Ambardekar AV, et al. A structured handoff program for interns. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):347–52.

Airan-Javia SL, Kogan JR, Smith M, Lapin J, Shea JA, Dine CJ, et al. Effects of education on interns’ verbal and electronic handoff documentation skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):209–14.

Wohlauer MV, Rove KO, Pshak TJ, Raeburn CD, Moore EE, Chenoweth C, et al. The computerized rounding report: implementation of a model system to support transitions of care. J Surg Res. 2012;172(1):11–7.

Salerno SM, Arnett MV, Domanski JP. Standardized sign-out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):121–6.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Simon, Barry Kamin, Melissa Cappaert, the staff of the GME Office, and all of the physicians who volunteered to be ‘trained-receivers’ for this project. We would also like to thank Kris Slawinski and the staff of the CPC for use of their facilities. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge Samantha Ngooi and Lisa Spampinato for their consistent logistical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funders

This work was funded by the University Of Chicago Pritzker School Of Medicine.

Prior Presentations

An earlier version of this report was presented at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine August 2014 Summer Research Project Forum in Chicago, IL and at the University of Chicago Medical Education Day November 2014 in Chicago, IL. This work was also presented as a poster at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Fall 2014 Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL. Finally, this work was presented at the Annual Symposium of the Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaffney, S., Farnan, J.M., Hirsch, K. et al. The Modified, Multi-patient Observed Simulated Handoff Experience (M-OSHE): Assessment and Feedback for Entering Residents on Handoff Performance. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 438–441 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3591-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3591-8