Abstract

Background

The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) and Care Transitions Measure (CTM-3) scores are patient experience measures used to determine hospital value-based purchasing reimbursement. Interventions to improve 30-day readmissions have met with mixed results, but less is known about their potential to improve the patient experience among older ethnically and linguistically diverse adults receiving care at safety-net hospitals. In this study, we assessed the effect of a nurse-led hospital-based care transition intervention on discharge-related patient experience in an older multilingual population of adults hospitalized at a safety-net hospital.

Methods

We randomized 700 inpatients aged 55 and older at an academic urban safety-net hospital. In addition to usual care, intervention participants received inpatient visits by a language-concordant study nurse and post-discharge phone calls from a language-concordant nurse practitioner to reinforce the care plan and to address acute complaints. We measured HCAHPS nursing, medication, and discharge communication domain scores and CTM-3 scores at 30 days after hospital discharge.

Results

Of 685 participants who survived to 30 days, 90 % (n = 616) completed follow-up interviews. The mean age was 66.2 years; over half (54.2 %) of the participants had cognitive impairment, and 33.8 % had moderate to severe depression. The majority (62.1 %) of interviews were conducted in English; 23.3 % were conducted in Chinese and 14.6 % in Spanish. Study nurses spent an average of 157 min with intervention participants. Between intervention and usual care participants, CTM-3 scores (80.5 % vs 78.5 %; p = 0.18) and HCAHPS discharge communication domain scores (74.8 % vs 68.7 %; p = 0.11) did not differ, nor did HCAHPS scores in medication (44.5 % vs 53.1 %; p = 0.13) and nursing domains (67.9 % vs 64.9 %; p = 0.43). When stratified by language, no significant differences were seen.

Conclusion

An inpatient standalone transition-of-care intervention did not improve patient discharge experience. Older multi-lingual and cognitively impaired populations may require higher-intensity interventions post-hospitalization to improve discharge experience outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Improving the patient experience, an element of the IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement) Triple Aim health care quality improvement initiative, is a priority for clinical leaders and policymakers.1 The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores are standardized measures of patient experience used to determine reimbursement in hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) arrangements.2,3 Since 2013, performance on HCAHPS domain scores have determined 0.3 % of participating hospitals’ diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments.4 Hospitals are expected to demonstrate improvement in measures or meet minimum quality thresholds to receive payment. In general, patient experience scores in safety-net hospitals are lower than those in non-safety-net hospitals,5–7 and the gap is widening.5 Safety-net hospitals serve patients of lower socioeconomic status, low health literacy, and limited English proficiency (LEP); these factors may negatively affect the provider–patient relationship and contribute to lower patient experience scores.8–10 As such, some concerns have been raised about the impact these policies have on safety-net hospitals and whether adjusting for socioeconomic status and social risk factors, including limited English proficiency and depression status, is appropriate for quality measurement and comparison.11

Transition-of-care activities present an opportunity to improve communication-related patient experience. These activities include educating patients about diagnoses, counseling them about medications, assessing discharge needs, and reinforcing follow-up. Poor communication in the peri-discharge period can lead to negative outcomes such as medication errors and readmissions.12–17 In recognition of the importance of transitions of care, a three-item version of the Care Transitions Measure (CTM-3) is now included in the HCAHPS survey.18,19

Few studies have examined the effect of transition interventions on the patient experience. Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge),20 a randomized controlled trial of an in-hospital patient education and discharge planning intervention, and the IMPaCT (Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets) study, a randomized controlled trial of a community health worker (CHW) intervention,21 both demonstrated improvements in patient experience measures. The C-TraIn (Care Transitions Innovation) study,22 a cluster-randomized controlled trial studying the effects of intensive transitional nurse coaching, pharmacy care, and community payment for primary care intervention showed improved CTM-3 scores in low-income English-speaking participants.

No studies to date have evaluated the impact of transition interventions on the patient experience in diverse older non-English-speaking populations. The Support from Hospitalization to Home for Elders (SHHE) study, a randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led transition-of-care intervention with post-discharge follow-up phone calls, found no reductions in 30-day readmission rates, and noted possible increases in ED visits.23 However, we posited that this intervention might improve patient experience through improved communication and the use of patient-centered discharge care planning. Therefore, we assessed the effect of the SHHE intervention on the patient experience in older English, Chinese- and Spanish-speaking adults hospitalized at a safety-net hospital, hypothesizing that participants receiving the intervention would have higher CTM-3 and HCAHPS scores in discharge communication, medication counseling, and nursing communication domains.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was part of the SHHE, a randomized controlled trial of a hospital-based care transition intervention designed to reduce ED use and hospital readmissions for adults aged 55 and older hospitalized at a safety-net hospital.23 The study was approved by the UCSF institutional review board.

Setting and Participants

Patients admitted to the internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, or neurology services at San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (SFGH) who were aged 55 and older and who spoke English, Spanish, or Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese) were eligible for enrollment. We excluded patients who had been transferred from an outside hospital, were admitted for a planned hospitalization, were likely to be discharged to hospice, nursing home, or other institutional settings, were unable to consent due to severe cognitive impairment, delirium, or severe mental illness, or were unable to participate in telephone follow-up.23

Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up

Study staff received a daily list of all patients admitted in the previous 24 h. After a preliminary review, study staff discussed eligibility with the patients’ attending physicians. Patients who were eligible were then approached by a language-concordant research assistant, who explained the study and obtained consent. Research assistants administered a baseline assessment prior to randomization. We used a parallel-group randomized design, stratified by language. Research assistants were blinded to participants’ randomization status during follow-up telephone interviews 30 days after hospital discharge.

Intervention

Usual Care

All study participants received usual care. The patient’s bedside registered nurse (RN) provided structured education, including information about follow-up appointments, and reviewed a discharge medication list, which was reconciled with pre-hospital medications. The RN gave the patient instructions on what symptoms should prompt return to the hospital. Social workers were available to assist with discharge needs. The inpatient team was responsible for transmitting the discharge summary to the patient's primary care provider within 3 days of discharge, and attempted to make post-hospitalization primary care visits within 2 weeks of discharge.

Intervention

In addition to receiving usual care, intervention group participants were visited by a study RN on the day of study enrollment and again within 24 h of discharge. The study RNs included native Spanish and Chinese speakers who were matched to study participants by language. Once the participant was randomized to the intervention group, the study RN notified the primary care provider by email to inform them that the patient had been admitted, along with contact information for the study RN and the primary medical team.

Disease-specific patient education, including symptom recognition, medication reconciliation, and strategies for navigating the health system, were provided by the study RN in the participant’s preferred language. Study RNs also organized post-discharge services for participants, confirming patients' understanding of services and reviewing time, location, and transportation plans for scheduled appointments, including instructions for arranging follow-up services, if necessary. Study RNs reconciled discharge medication regimens and explained medication instructions, emphasizing any changes, proper administration of medications, and potential side effects. They also reviewed with participants the appropriate steps to take if problems arose, and provided contact numbers and instructions for contacting primary care providers or emergency services. The study RNs used motivational interviewing24 techniques to foster positive self-care and health behaviors, and used Krames Patient Education25 language-concordant written educational materials to supplement verbal instructions. They reinforced their teaching using the “teach-back” method to ensure patient comprehension.26 In order to improve intervention participants’ ability to receive the intervention, study RNs worked with caregivers (both family and non-family) to include them in the education and training activities.

At discharge, participants were given a booklet, the "After Hospital Care Plan" (AHCP), which was written in their native language and was conceptually similar to that used in Project RED.20 The AHCP included the reason for hospitalization, principal diagnoses and important findings, a reconciled discharge medication list, and primary care and pharmacy contact information and upcoming appointments. Based on feedback from pilot testing, we simplified the AHCP by changing the presentation of medications.

After hospital discharge, nurse practitioners (NPs) from the study team contacted intervention participants via telephone once on post-discharge days 1–3 and again on days 6–10. These calls were made by language-concordant NPs or, if a language-concordant NP was not available, using a trained medical telephone interpreter. The NPs provided patient education on symptoms, assessed adherence to medications and treatment plans, helped patients resolve barriers to attending follow-up appointments, and discussed other issues identified in the participants' personalized discharge plans. They answered questions about and adjusted medications, worked with pharmacies to resolve prescription problems, and, if necessary, referred patients to their primary care provider, urgent health clinic, or emergency department. Study NPs contacted patients’ primary care providers if there were any changes in clinical status, new reported symptoms, or medication adjustments. Participants had access to a phone support line staffed by an NP who returned phone calls within 24 h.

Dependent Variables

HCAHPS Domains of Patient Experience

Developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and introduced in 2008, the HCAHPS asks patients 25 questions regarding their experience in the hospital. Patients are asked to respond to questions either using a four-point Likert scale (“always,” “usually,” “sometimes,” or “never”) or with “yes” or “no.”3 Of these 25 questions, 14 are summarized and reported in six summary domain scores, which include communication with nurses, communication with physicians, communication about medications, adequacy of planning for discharge, responsiveness of staff, and pain management.27 We measured the impact of the intervention on the discharge communication domain, the outcome most likely to have been affected by the intervention. We also assessed medication and nursing domains, recognizing that these encompass the entire hospitalization, including the discharge period. We calculated the HCAHPS domain scores by determining the “top-box” score that CMS uses to report HCAHPS scores. Top-box scores represent the proportion of participants who responded with “always” to all questions in a particular domain, with a higher proportion indicating better quality.3 For the HCAHPS questions regarding discharge communication, we determined the proportion of respondents responding “yes” to both questions (Text Box 1).

Text Box 1 HCAHPS Domains, CTM-3 Questions, and Discharge Medication Counseling Questions Asked at 30-Day Follow-Up Interview

Discharge Communication* |

1. During this hospital stay, did doctors, nurses or other hospital staff talk with you about whether you would have the help you needed when you left the hospital? (Y/N) |

2. During this hospital stay, did you get information in writing about what symptoms or health problems to look out for after you left the hospital? (Y/N) |

Medication Communication† |

1. Before giving you any new medicine, how often did hospital staff tell you what the medicine was for? |

2. Before giving you any new medicine, how often did hospital staff describe possible side effects in a way you could understand? |

Nursing Communication† |

1. During this hospital stay, how often did nurses treat you with courtesy and respect? |

2. During this hospital stay, how often did nurses listen carefully to you? |

3. During this hospital stay, how often did nurses explain things in a way you could understand? |

Care Transitions Measure-3 Questions‡ |

1. During this hospital stay, staff took my preferences and those of my family or caregiver into account in deciding what my health care needs would be when I left. |

2. When I left the hospital, I had a good understanding of the things I was responsible for in managing my health. |

3. When I left the hospital, I clearly understood the purpose for taking each of my medications. |

Discharge Medication Counseling Question* |

1. During this hospital stay, did someone on the hospital staff explain the purpose of the medicines you were to take at home in a way you could understand? |

* Yes or No

† Four-point Likert scale: 1, Never; 2, Sometimes; 3, Usually; 4, Always

‡ Four-point Likert scale: 1, Strongly disagree; 2, Disagree; 3, Agree; 4, Strongly agree

Three-Item Care Transitions Measure (CTM-3)

The CTM-3,18 which consists of three questions, assesses the quality of the transitional care experience (Text Box 1).28 The CTM-3 was incorporated into the HCAHPS survey questionnaire beginning in January 2013.19 We summed and linearly transformed mean scores for each CTM-3 question to obtain a score ranging from 1 to 100. We also calculated a “top-box” score for each individual CTM-3 question.

Baseline Measures

At the baseline interview, participants reported date of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, total household income (≤$20,000 per year vs >$20,000 per year),29 and last completed grade in school (categorized as 0–6 years, 7–11 years, 12 years, and >12 years). We asked what language the participant spoke at home, and how well the participant spoke English (we defined low English proficiency for participants indicating “not at all/not well”).30 We measured substance use (using the World Health Organization [WHO] Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test [ASSIST]),31,32 depression symptom severity using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (we defined moderate-severe depressive symptoms by a PHQ-9 score ≥10),33,34 and self-reported health literacy (a score ≥ 9 was defined as an adequate health literacy score).35,36 We asked participants whether they identified a usual place of care and regular health care provider, and whether they had experienced emergency department visits or hospitalizations in the 6 months prior to study enrollment. Research assistants administered the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) to evaluate cognitive impairment, defined as a TICS score less than 20.37 We calculated the Charlson comorbidity index using administrative ICD-9 codes from the index hospitalization (scores 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+, higher scores indicate higher mortality risk).38

Statistical Analysis

While our study was originally powered for readmission rate reductions, we estimated that our sample size was large enough to detect a 5 % effect size difference between HCAHPS and CTM scores based on a prior published study.18 We compared patient characteristics between treatment and control groups using chi-square tests. As the CTM-3 scores were not normally distributed, we used nonparametric tests of significance to compare scores between groups. Because we used stratified randomization by language a priori, we conducted a secondary analysis examining the outcome measures by language. We conducted sensitivity analyses to account for communication experience not affected by the intervention by comparing the proportions reporting “usually” or “always” versus other answers between groups. We accounted for missing responses by conducting sensitivity analyses coding missing data as “no” or “never” responses. Because we hypothesized that patients with depression might respond to the intervention differently from patients without depression, we conducted a post hoc analysis stratified by depression. Data analysis was conducted using the Stata version 13 software program (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Role of the Funding Source

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation funded this study. The funding source had no access to the data or role in design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Study Patients

During the study period, 6384 inpatients met basic inclusion criteria, from which 1781 were eligible for screening (Fig. 1). After screening, 912 inpatients were ineligible, and an additional 169 declined to participate. We randomized the remaining 700 participants. Of the 685 who survived to 30 days, 90 % (n = 616) completed follow-up research interviews.

Study eligibility, enrollment, and telephone interview completion. §Excluded prior to screening: non-study language (n = 466); planned admission (n = 101); screened out by team (n = 917); previously enrolled in pilot or RCT (n = 551); previously refused (n = 82); less than 24-h stay (n = 1350); discharged before assessment (n = 94); transfer to other service (n = 233); transfer to/from institution (n = 809). †Excluded at screening: no phone/homeless (n = 583); lives elsewhere (n = 46); left hospital before enrollment completed (n = 111); failed teach-back (n = 96); declined (n = 169); other (n = 76)

The study sample was an ethnically diverse low-income population with limited educational background and health literacy. The mean age was 66.2 years (SD 9.0). Blacks made up 24.4 % of the population, 19.0 % were white, 32.2 % were Asian, and 19.6 % were Latino. Over half (62.1 %) of the interviews were conducted in English; 23.3 % were in Chinese and 14.6 % in Spanish. Over one-third of participants noted limited English proficiency (37.1 %), and more than half (51.6 %) had limited health literacy. Over half (54.5 %) of the study population met criteria for cognitive impairment at baseline, and one-third (33.8 %) met criteria for moderate to severe depression. More than one-third (35.1 %) of participants lived alone. Over one-third (35.9 %)of the study population had a Charlson score of 3 or above. Overall, 77.2 % of the participants could name a regular health care provider. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups (Table 1).

Process Measures

We measured several aspects of intervention implementation. The in-hospital study RN spent a total of 156.6 min (SD 102.0) on one-on-one patient care and care coordination issues. The post-discharge study NP completed at least one follow-up phone call for 94.5 % of patients, and completed both follow-up phone calls for 82.8 % of the intervention participants.

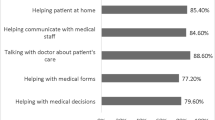

Outcomes Measures

At 30-day follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and usual care groups in the CTM-3 score (80.5 % vs 78.5 %; p = 0.18) or the HCAHPS discharge communication domain score (74.8 % vs 68.7 %; p = 0.11). There were also no differences in HCAHPS scores in medicine communication (44.5 % vs 53.1 %; p = 0.13), or nurse communication (67.9 % vs 64.9 %; p = 0.43) (Table 2). No differences between groups were found when the results were stratified by interview language (Table 3). There was also no significant difference between groups when participants reporting “usually” or above were included as a positive response, or when missing data were recoded as a negative response (data not shown). When we stratified by depression status, we found that among non-depressed participants, those in the intervention had higher patient experience scores than those in usual care, although these did not always reach statistical significance. Patients with depression showed no difference (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study found that a nurse-led transition-of-care intervention in older linguistically diverse adults admitted to a safety-net hospital did not impact communication-related patient experience. We hypothesized that the intervention’s specially trained study RNs working one-on-one with the patient to devise a patient-centered discharge plan would improve communication-related patient experience measures, but it did not. We suggest that high rates of cognitive impairment and depression may have interfered with participants’ ability to benefit from the intervention. While other studies have shown modest effects on patient experience, our results reflect the challenges in improving patient experience in older adults with limited English proficiency, cognitive impairment, and depression.

While it is clear that the patient experience is an important component in providing quality care,27,39,40 it is not clear what interventions are effective in improving the patient experience. Our intervention was modeled after Project RED,20 which showed improvement in patient experience measures that were similar to the HCAHPS and CTM-3 measures. In Project RED, the study population was younger, was English-speaking, and had less cognitive impairment, which could have made the participants more amenable to the intervention. The IMPaCT trial with a community health worker intervention reported higher scores on one HCAHPS question (“Did you receive high-quality verbal discharge communication?”).21 The differences in interventions may explain why the IMPaCT study demonstrated improved patient experience and ours did not. The use of lay persons who shared socioeconomic backgrounds with them and who continued working with patients post-hospitalization may have been more effective in communicating and reinforcing patient-centered discharge information. Similarly, the improved CTM-3 scores in the C-TraIn study,13 which involved a high-intensity nurse coaching and post-discharge linkage intervention in a younger, low-income population, may have been due to the continuity of care provided by the study nurse and post-discharge home visits to reinforce the care plan.

There are several reasons why our intervention may not have worked. The patient experience is likely influenced by the quality of interactions between patients and their providers, individual patient factors and health expectations, and the hospital environment. While the HCAHPS questionnaire focuses on the in-hospital experience, participant responses may be influenced by post-hospitalization interactions with health care providers. Our intervention’s follow-up phone calls and access to “warm lines” may not have been enough to reinforce participants' understanding of care plans.

Our study population had high rates of cognitive impairment and depression and low levels of social support, and this may have affected the ability of the intervention to improve the patient experience. Depression is associated with difficulties related to health care 41 and patient-physician communication.42,43 In addition to coloring patients’ view of the care that they received, depression may interfere with patients’ ability to respond to interventions that focus on self-efficacy and education. While our findings on depression are exploratory, they provide insight into why we found no improvement in patient experience and may guide future research efforts.

Our intervention was a standalone enhancement provided alongside usual care, and did not address aspects of hospital culture such as timeliness of care delivery and nurse staffing ratios.27,44–47 We did not alter the usual care provider–patient interactions, which may have been necessary to improve HCAHPS nursing communication and medication communication domain scores that reflect the participants’ experience throughout the entire hospitalization.

This study has several limitations. Primary medical teams were not blinded to the presence of the study RN intervention; it is possible that the bedside nurses adopted some of the teaching techniques used by the study RN, improving the care of all patients and impeding our ability to find an effect. The measures of patient experience we included, though widely used, have not been validated in low-income, limited-literacy populations, and thus may not have been well-understood by participants.

CONCLUSIONS

A nurse-led education-based transition-of-care intervention did not improve the patient experience at discharge. Our finding on the lack of improvement in patient experience in this population underscores the importance of designing pay-for-performance programs such that they do not widen existing health disparities. Designs of future care transition interventions in older safety-net populations with cognitive impairment and depression may require additional supportive post-discharge intervention in order to improve the patient experience.

References

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27:759–69.

Blumenthal D, Jena AB. Hospital value-based purchasing. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2013;8:271–7.

Giordano LA, Elliott MN, Goldstein E, Lehrman WG, Spencer PA. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2010;67:27–37.

Medicare and Medicaid programs: hospital outpatient prospective payment; ambulatory surgical center payment; hospital value-based purchasing program; physician self-referral; and patient notification requirements in provider agreements. Final rule with comment period. Federal register 2011;76:74122–584.

Chatterjee P, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient experience in safety-net hospitals: implications for improving care and value-based purchasing. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1204–10.

Goldman LE, Vittinghoff E, Dudley RA. Quality of care in hospitals with a high percent of Medicaid patients. Med Care. 2007;45:579–83.

Borah BJ, Rock MG, Wood DL, Roellinger DL, Johnson MG, Naessens JM. Association between value-based purchasing score and hospital characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:464.

Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800–6.

Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V. When seeing the same physician, highly activated patients have better care experiences than less activated patients. Health Aff. 2013;32:1299–305.

Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott M, Pradhan R, Schiller C, Hall A, Hays RD. Can hospital cultural competency reduce disparities in patient experiences with care? Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S48–55.

Fiscella K, Burstin HR, Nerenz DR. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: to adjust or not to adjust. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312:2615–16.

Parry C, Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank J, Kramer AM. The care transitions intervention: a patient-centered approach to ensuring effective transfers between sites of geriatric care. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2003;22:1–17.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–8.

Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2004;170:345–9.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–7.

Bull MJ. Patients' and professionals' perceptions of quality in discharge planning. J Nurs Care Qual. 1994;8:47–61.

Coleman EA, Williams MV. Executing high-quality care transitions: a call to do it right. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2007;2:287–90.

Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient's perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;43:246–55.

Parry C, Mahoney E, Chalmers SA, Coleman EA. Assessing the quality of transitional care: further applications of the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2008;46:317–22.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–87.

Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, et al. Patient-centered community health worker intervention to improve posthospital outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014.

Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The Care Transitions Innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014.

Goldman LE, Sarkar U, Kessell E, et al. Support from hospital to home for elders: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:472–81.

Searight HR. Efficient counseling techniques for the primary care physician. Prim Care. 2007;34:551–70.

Huang L. Krames On-Demand (KOD). J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94:234–5.

Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90.

Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921–31.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2, e02.

Operario D, Adler NE, Williams DR. Subjective social status: reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychol Health. 2004;19:237–46.

USC B. English proficiency question U.S. summary: 2000 Census US Profile. Washington DC. 2000.

Group TWAW. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–94.

WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–94.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44.

Reuland DS, Cherrington A, Watkins GS, Bradford DW, Blanco RA, Gaynes BN. Diagnostic accuracy of Spanish language depression-screening instruments. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:455–62.

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–94.

Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Lopez A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:265–71.

Barber M, Stott DJ. Validity of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) in post-stroke subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2004;19:75–9.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27:S110–27.

Alazri MH, Neal RD. The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2003;20:486–90.

Martino SC, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Farley DO, Burkhart Q, Hays RD. Depression and the health care experiences of Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1883–904.

Swenson SL, Rose M, Vittinghoff E, Stewart A, Schillinger D. The influence of depressive symptoms on clinician-patient communication among patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Care. 2008;46:257–65.

Schenker Y, Stewart A, Na B, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms and perceived doctor-patient communication in the Heart and Soul study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:550–6.

Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1988;260:1743–8.

Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manage Care. 2011;17:41–8.

Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:188–95.

Kutney-Lee A, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, et al. Nursing: a key to patient satisfaction. Health Aff. 2009;28:w669–77.

Acknowledgments

Brian Chan is supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32HP19025).

L. Elizabeth Goldman, Urmimala Sarkar, Michelle Schneidermann, Eric Kessell, David Guzman, Jeffrey Critchfield, and Margot Kushel were supported by funds from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (grant #1836).

L. Elizabeth Goldman is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 RR024130.

Presentations

Results from this study were presented at an oral presentation at the national SGIM meeting in San Diego, April, 2014.

Role of the Funding Source

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation funded this study. The funding source had no access to the data or role in design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

NIH trials registry number: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01221532

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, B., Goldman, L.E., Sarkar, U. et al. The Effect of a Care Transition Intervention on the Patient Experience of Older Multi-Lingual Adults in the Safety Net: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 1788–1794 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3362-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3362-y