Abstract

Introduction

Acquired angioedema (AAE), an acquired deficiency of C1esterase inhibitor, is a medically treatable condition which can cause severe abdominal pain mimicking an acute surgical abdomen. This disorder is strongly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other indolent lymphoplasmacytic disorders.

Discussion

We describe a patient with known CLL who developed incapacitating, recurrent severe abdominal pains, culminating in partial bowel resection. Signs, symptoms, laboratory and pathologic findings demonstrated AAE.

Conclusion

Wider appreciation of the possibility of AAE, particularly in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, could lead to preventive therapy and spare unnecessary surgery. This is more important now that more effective medical therapies are available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acquired angioedema (AAE) is due to acquired deficiency of C1 inhibitor (C1Inh), resulting in excessive complement and bradykinin activities. Blood vessel permeability is increased; thus, angioedema occurs. Just as with hereditary angioedema (hereditary C1Inh deficiency; HAE), common clinical manifestations are skin swelling, laryngeal edema, and/or abdominal pain.1,2

AAE often occurs in the context of lymphoplasmacytic disorders, such as monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1,3 Among 32 patients with AAE, Castelli found that 13 (40%) had MGUS and 9 (28%) had lymphoproliferative disease.3 Therefore, all cases of AAE should be evaluated for the possibility of underlying lymphoplasmacytic disorder. Conversely, when patients with known lymphoproliferative disease manifest compatible symptoms, AAE should be expeditiously considered. This is important because AAE can be effectively treated medically, but delayed diagnosis can lead to unnecessary diagnostic procedures, therapeutic interventions, or life-threatening complications, well-illustrated by our case.

Case Presentation

A 78-year-old woman with atherosclerotic vascular disease was transferred to our hospital with abdominal pain and underwent emergent laparotomy. One year earlier, she had been diagnosed with Rai Stage I CLL which had been observed without treatment. Two months earlier, she presented with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Over the next 8 weeks, she had six emergency room and/or hospital admissions for identical symptoms. The episodes left the patient weak and incapacitated. Pains would begin at rest in the lower abdomen, spread to the upper abdomen, described as “gas-like”, non-radiating, constant. There was no association with meals, exertion, or bowel movements. Subsequent vomiting was nonbloody, nonbilious, and did not relieve the pain. Episodes resolved spontaneously within 2–3 days with intravenous hydration and pain control. Extensive evaluation included colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance angiography, and abdominal aortography. Benign colon polyps and small gallstones were removed, mesenteric stenoses ruled out, yet pains recurred unabated. She had lost 12 lbs. There was no dysphagia, change in bowel habits, GI bleeding, fever, or sweats. Medications included baby aspirin, clopidogrel, benazepril, hydrochlorothiazide, and glipizide.

Physical examination on transfer revealed blood pressure 130/88 mmHg, pulse 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 cycles per minute, pulse oximetry of 95% on ambient air, and temperature 97.0°F. The patient was in acute distress due to abdominal pain. Left cervical and axillary lymph nodes were enlarged to 1.5 cm in diameter. Cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. Abdomen was slightly distended, diffusely exquisitely tender with guarding and rebound. Bowel sounds were hypoactive. Rectal examination showed guaiac-negative brown stool.

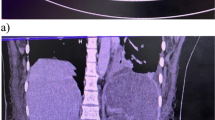

Hemoglobin was 18.1 g/dL, hematocrit 55%, platelets 146 × 109/L, and leukocytes elevated to 34,500 cells/μL with 47% neutrophils and 48% lymphocytes. Chemistries and liver function tests were normal. Abdominal X-ray showed no free air, nor air-fluid levels. CT scan of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showed multiple abnormal loops of small bowel with contrast-enhanced bowel wall edema (Fig. 1a).

At laparotomy, massively swollen small bowel was encountered and resected. Pathologic examination revealed massive submucosal edema (Fig. 1b). There was no leukemic infiltration visible.

A hematology consultant, called postoperatively, suspected AAE. C4 was 3 mg/dL (normal 17–46), C3 66 mg/dL (85–200), and C1Inh activity reportedly 83% (68–200%). Serum protein electrophoresis revealed two faint bands immunofixing as monoclonal IgM kappa and IgG kappa. Chlorambucil was started for CLL and danazol to raise C1Inh. Lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy improved and C1Inh activity increased to 110%. Over 3 years of follow-up, abdominal symptoms never recurred.

Discussion

Approximately 145 cases have been reported of AAE,3 and this is one of four cases that we have diagnosed in the last decade with abdominal pains from AAE with associated CLL. Table 1 shows characteristics of patients with CLL and AAE we have seen (some briefly mentioned in a prior report).4 This is our only case to undergo surgery, allowing unique and dramatic demonstration of massive bowel edema visible radiographically, on surgical inspection and on histopathology. An initial C1Inh activity was reported low normal, but there can be no doubt about the diagnosis based on radiologic/surgical/histologic findings, further laboratory results, and the clinical course. Characteristic are very low C4 level and low C3; diagnostic recommendations currently add C1q and anti-C1Inh antibody levels. Autoantibody is demonstrable in up to 70% with AAE.1 Our patient had monoclonal gammopathy, which frequently corresponds to the C1Inh autoantibody. Patients with the hereditary form (HAE) usually manifest before age 20 and give a family history of symptoms. In all our patients with CLL and AAE, chemotherapy and androgens increased C1Inh and produced durable remission.

Angioedema should be borne in mind among “medical” illnesses that can mimic acute surgical abdomen, along with such other disorders as porphyria, Familial Mediterranean fever and sickle cell disease (Fig. 2). One may need to discern whether a true surgical emergency might supervene even when one of these disorders is present. Our patient had typical symptoms of acute bowel edema, including diffuse abdominal pain, occasionally rebound tenderness and vomiting, with spontaneous resolution within 1–5 days.1,2 Some patients with AAE have cutaneous or upper respiratory edema in addition, or instead of, bowel symptoms. Because of cardiovascular comorbidities, there was a high suspicion for ischemic bowel in our patient, but radiography and endoscopy did not support this. In the differential diagnosis, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors rarely precipitate angioedema, but our patient had taken benazepril many years and continued it without incident after AAE therapy.

In 2009, the US FDA approved the C1Inh concentrate Berinert P® and the kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide (Kalbitor®) for treatment of acute attacks, and the C1Inh concentrate Cinryze® for prophylaxis in severely affected patients.5 Fresh frozen plasma can be given when these are unavailable. C1Inh concentrates are highly safe and effective; the standard of care for decades in other countries, but US approval was delayed by concerns of virus transmissibility.1,5–9 Doses used in the clinical HAE trials may need to be higher for AAE because of increased enzyme clearance. Ecallantide is subcutaneous, facilitating patient self-administration out of hospital. A bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant (Firazyr®) is under investigation. For long-term control, the underlying cause should be addressed, CLL in our case. Commonly used for prophylaxis are anti-fibrinolytic drugs or the attenuated androgen danazol, which increases C1Inh synthesis at low cost.10

In conclusion, earlier suspicion for AAE in our known CLL patient could have spared her the morbidities of recurrent abdominal pains, hospitalizations, morbid interventions, and bowel resection. Wider appreciation of this disorder takes on added importance as our ability to effectively treat the problem has grown.

References

Cicardi M, Zanichelli A. Angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency in 2010. Intern Emerg Med. 2010; doi:10.1007/s11739-010-0408-3.

Eck SL, Morse JH, et al. Angioedema presenting as chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(3):436–9.

Castelli R, Deliliers DL, et al. Lymphoproliferative disease and acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency. Hematologica/the hematology journal. 2007;92:5:716–718.

Jung M, Rice L. Unusual autoimmune non-hematologic complications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011 (In press).

Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angiodedma. N Engl J Med. 2010;262:513–22.

Gadek JE, Hosea SW, Gelfand JA et al. Replacement therapy in hereditary angioedema: successful treatment of acute episodes of angioedema with partly purified C1 inhibitor. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:542–546.

Waytes AT, Rosen FS, Frank MM. Treatment of hereditary angioedema with a vapor-heated C1 inhibitor concentrate. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1630–4.

Kunschak M. Engl W, Maritsch, et l. A randomized, controlled trial to study the efficacy and safety of C1 ihibitor concentrate in treating hereditary angioedema. Transfusion. 1998;38:540–9.

Morgan BP. Hereditary angioedema—Therapies old and new. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:581–583.

Bork K, Bygum A, Hardt J Benefits and risks of danazol in hereditary angioedema: a long-term survey of 118 patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:153–161.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, M., Rice, L. “Surgical” Abdomen in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case of Acquired Angioedema. J Gastrointest Surg 15, 2262–2266 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1718-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1718-0