Abstract

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO), acting under the authority of the International Health Regulations (IHR), recommended against the imposition of trade or travel restrictions because, according to WHO, these barriers would not prevent disease spread. Why did 47 states impose barriers anyway? This article argues that states use barriers as political cover to prevent a loss of domestic political support. This logic suggests that governments anticipating high domestic political benefits for imposing barriers during an outbreak will be likely to do so. Logistic regression and duration analysis of an original dataset coding state behavior during H1N1 provide support for this argument: democracies with weak health infrastructure—those that stand to gain the most from imposing barriers during an outbreak because they are particularly vulnerable to a negative public reaction—are more likely than others to impose barriers and to do so quickly.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

On March 18, 2009, authorities in Mexico discovered the first cases of H1N1 influenza (originally referred to as Swine Flu). Cases steadily rose in Mexico in the following weeks, and on April 24, the United States (US) reported seven confirmed cases of the virus. Over the next three months, H1N1 spread to almost every country in the world.

Through the International Health Regulations (IHR), the World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for coordinating the global response to major disease outbreaks like H1N1. On April 26, WHO declared H1N1 an international public health emergency. WHO also recommended that states not impose trade and travel restrictions because, according to the organization, such measures would not stop H1N1 from spreading (World Health Organization 2009a, e). Despite this guidance, 47 of 193 WHO member states imposed trade or travel barriers against H1N1-affected countries. Whether or not barriers actually protect from the spread of disease, this variation in state behavior is puzzling and not easily explained by vulnerability to disease spread, geographic location, economic size, or trade ties.

State behavior during H1N1 reflects a longstanding pattern: states have often imposed trade and travel restrictions during outbreaks that on their face seem like they would prevent disease spread, but that public health experts actually deem ineffective.Footnote 1 Importantly, the use of these barriers has an unintended consequence that makes all states more vulnerable to future outbreaks. Namely, barriers lead to a commitment problem that encourages outbreak concealment. Since states cannot credibly commit to not impose costly barriers, outbreaks are chronically underreported. Not surprisingly, states will not rapidly and transparently report outbreaks if economic harm is their reward. In an attempt to overcome this collective action problem, states revised the IHR in 2005 by delegating increased authority to the WHO. In particular, states agreed to follow the organization’s recommendations about the health measures that states should (or should not) impose during an outbreak. H1N1 put the new regulations to the test for the first time and close to 25 % of states ignored WHO guidance.

This article investigates the role played by domestic politics in governments’ decision to either impose barriers or to follow WHO recommendations against them. Barriers are an attractive policy because they can quell public fear and instill confidence in the government by signaling to domestic constituents that the state is taking action to protect them from a potentially dangerous threat. Thus, for governments looking to counter charges of not protecting the population from disease, I argue that barriers provide “political cover.” As a result, states should be likely to impose barriers during an outbreak when they anticipate domestic political gains for doing so.

Following this logic, the central contention is that the strength of democratic institutions, together with the state’s capacity to respond to the outbreak, influences the domestic political costs and benefits of imposing barriers. Specifically, democratic states should be more likely to impose barriers and disregard WHO recommendations when they have weak health infrastructure. Democracies are particularly dependent on public support and so are especially sensitive to the public’s reaction to policy choices during an outbreak. And, if the outbreak crosses the border, states that lack the capacity to launch an effective response anticipate a negative public reaction to the government’s handling of the outbreak. We know that democratic institutions do not always lead to international cooperation, and can sometimes actually incentivize governments to forsake institutional commitments (Dai 2006, 2007). This article sheds light on this counterintuitive dynamic in the case of the IHR and international public health emergencies.

Using an original dataset, I evaluate this argument through an examination of the behavior of the 193 WHO member states during the H1N1 pandemic. Consistent with the argument outlined above, logistic regression and duration analysis reveal that the effect of the quality of health infrastructure is conditional on the level of democracy. And, democracies with weak health infrastructure are more likely than others to impose barriers, and to do so quickly. Importantly, these findings hold even when controlling for alternative explanations such as vulnerability to disease spread, vulnerability to US retaliation, the level of trade exposure, regional policy diffusion, and domestic commitment to the rule of law.

Two factors make this case particularly instructive for evaluating the role of domestic politics in whether states follow through with institutional commitments. First, it overcomes the selection problem that confronts many studies of state behavior under international organizations (IOs), namely that states might only make institutional commitments that they intend to follow (Von Stein 2005). At the time of H1N1, all states except for Liechtenstein were parties to the IHR. Therefore, because no particular type of state was more or less likely to sign on to the IHR, state parties to the regulations do not only represent the most cooperative states that are most likely to follow WHO recommendations. Second, it poses a hard test for domestic level factors. The US had one of the highest numbers of cases of H1N1 and so the vast majority of states imposing barriers targeted the US and risked antagonizing the world’s most powerful state. If domestic politics matters here even when international costs should predominate—and I find that it does—then we can expect it to operate in other contexts as well.

The study offers several contributions to existing scholarship. The first is theoretical. The proposition that electoral accountability can sometimes discourage compliance has not been widely tested in different contexts, leaving unanswered questions about how leaders assess the compliance preferences of constituents across issue areas. In examining the conditions under which democracies are likely to impose barriers during a disease outbreak even when WHO recommends against such behavior, I show that state capacity—in this case, health capacity specifically—influences the domestic political incentives that democratic leaders face when deciding whether to follow through with their commitments under the IHR.

Second, the article specifies and tests a mechanism through which public pressures influence government decision making. Domestic pressures could operate in two ways: governments could react and adopt a policy in direct response to constituent demands, or governments could proactively adopt a policy in anticipation of constituent demands. In examining variation in the speed with which states impose barriers, I find evidence in support of the latter mechanism. Leveraging variation in the timing of compliance or non-compliance can be used to distinguish between these alternative mechanisms in other issue areas as well.

A third contribution is empirical. A growing research agenda studies WHO, the IHR, and global health issues generally (e.g., Chorev 2012; Davies et al. 2015; Graham 2014; Gronke 2015; Hanrieder 2014; Kamradt-Scott and Rushton 2012; Youde 2014), but scholars have yet to systematically examine variation in the use of barriers during outbreaks. Outbreaks that demand international action have increased in recent years and will be a constant for the foreseeable future (Institute of Medicine 2010; Jones et al. 2008; Morens et al. 2008); this study draws on the IO scholarship to provide insight into the challenges facing successful cooperation in this area.

The article proceeds as follows. The next section provides background on the IHR and the credible commitment problem that undermines outbreak response efforts. Then, I review existing explanations for state adherence (or not) to institutional commitments and their relevance for the IHR. The next section presents the argument that governments use barriers as political cover. I then review the data and methods before testing my argument against alternatives and discussing the empirical results. The final section concludes by outlining implications for outbreak response, the IHR, and the study of IOs generally.

2 Background: Barriers, outbreak concealment, and the IHR

Since their inception, a central aim of the IHR has been to encourage rapid outbreak reporting because such reporting increases the effectiveness of outbreak response (Giesecke 2000). Efforts to encourage rapid reporting by states often fall short, however, because they must overcome the above-described commitment problem.Footnote 2 States that discover outbreaks within their borders conceal them because other states cannot credibly commit to not impose costly barriers in response.Footnote 3 This behavior reveals that states have time-inconsistent preferences, meaning that their long and short-term preferences regarding outbreak response conflict. Though in the long run all states are in favor of limiting the use of barriers to encourage early reporting and facilitate outbreak containment, when an outbreak occurs, conditions change and states forgo this longer-term collective good by succumbing to short-term incentives to impose barriers.

Evidence of outbreak concealment due to fear of economic costs dates back to the “Black Death” plague epidemics in medieval Europe. Local health authorities often understated the extent of that outbreak to prevent the economic damage of emergency health measures such as quarantine and the closure of trade routes (Porter 1999; see also, von Tigerstrom 2005, 42). This dynamic also unfolded during more recent outbreaks such as the 1991 cholera outbreak in Peru and the 1994 outbreak of plague in India (Carvalho and Zacher 2001; Cash and Narasimhan 2000). A high profile example was China’s concealment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and other states’ imposition of overly restrictive measures when SARS was finally made public (Mackey and Liang 2012).

In 2005, states revised the IHR and delegated increased authority to WHO during disease outbreaks.Footnote 4 Two changes directly targeted the above-described commitment problem. First, the revised IHR empower WHO to make real-time recommendations to states about how to respond to a given outbreak, including whether or not states should impose trade or travel barriers. Second, WHO was given the authority to “name and shame” states for not following these recommendations. Though these recommendations are not legally binding—states can, within certain limits, impose measures that WHO does not endorse—disregarding WHO guidance against imposing barriers without compelling scientific justification clearly undermines the purpose of the IHR, which is “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” (Article 1.1). Signing on to the IHR in 2005 signaled a commitment by states to uphold this goal.Footnote 5 The hope was that by creating a focal point for state behavior, and allowing WHO to monitor and publicize that behavior, states would follow WHO guidance and refrain from imposing barriers when the organization deemed they would not prevent disease spread.

However, in spite of signing on to the revised IHR, as H1N1 makes clear, some states continue to ignore WHO guidance during outbreaks.Footnote 6 Understanding the continued use of barriers is critical to minimizing the potentially devastating consequences of these global health emergencies. Though three-fourths of WHO member states followed WHO’s recommendations, even just a few states imposing barriers can lead to significant economic losses for states suffering from the outbreak and cause enough damage to produce incentives to conceal. For example, during the spring of 2009 alone, Mexico—the state where H1N1 originated—lost $2.3 billion in trade (Mackey and Liang 2012, 122). Therefore, if states continue to impose costly restrictive measures, incentives to conceal outbreaks will persist and efforts to respond to them will continue to fall short.

So, why do some states still ignore WHO guidance? Explanations for why states do (or do not) follow through with their institutional commitments offer a good starting point. The next two sections apply this work to the IHR and then lay out the argument connecting the use of barriers to domestic political institutions and health capacity.

3 Why states abide by institutional commitments (or not)

Though scholarship directly addressing the IHR and the use of barriers during outbreaks is limited, the question of why states do or do not abide by their institutional commitments generally is well-studied (Martin and Simmons 1998; Simmons 2010). Existing explanations focus on material and normative factors either at the international or domestic level. Though each of these approaches can be easily applied to the IHR, as the following discussion describes, there are reasons to suspect that domestic political factors play a prominent role in whether or not states impose barriers during an outbreak.

Some scholars look to geopolitical interests and argue that states are driven by fear of punishment from other states in the form of withholding aid, trade, and cooperation in other areas (Keohane 1984; Simmons 2000a; Simmons and Elkins 2004). From this perspective, reputation and reciprocity matter most and states base their compliance behavior on those other states most able to dole out material or normative punishment for undesirable behavior. Curiously, in the case of the IHR, the possibility of retaliation by the US for unwarranted trade restrictions did not stop nearly one-quarter of states from imposing barriers.

In the only existing examination of the use of barriers during disease outbreaks, Kamradt-Scott and Rushton (2012) focus on the power of international norms. Treating international institutions as norm propagators (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Lutz and Sikkink 2000), they contend that the revised IHR represent a new norm to not impose overly restrictive trade and travel barriers during outbreaks. They argue that this norm has been internalized by most states since the majority followed WHO recommendations during H1N1. While many states did abide by WHO recommendations, why 25 % of states acted against this norm is an open question.

Others focus on the role of domestic level factors. Since many international agreements are not self-enforcing, threaten limited international costs for non-adherence, and empirical evidence suggests that most states follow through with their international commitments most of the time, some argue that a lack of capacity at the domestic level impedes states’ ability to follow through with their commitments (Chayes and Chayes 1998; Mitchell 1994; Weiss and Jacobson 2000; Simmons 2002; Tallberg 2002; Cole 2015; Gray 2014). From this perspective, states generally want to abide by their commitments, but doing so often requires legal, bureaucratic, economic, or other specialized expertise, not to mention absolute political control, that many states lack. However, abiding by commitments to the IHR and following WHO guidance to not impose trade or travel barriers requires no special capacity. As such, weak state capacity alone cannot explain why many states did not follow WHO advice.

While capacity to meet treaty requirements may be a prerequisite for complying, the assumption that states would comply if only they could glosses over the reality that compliance decisions can affect domestic constituents and have political implications for governments that are often primarily concerned with their political fortunes (e.g., Kelley 2007; Simmons 2009; see also, Martin and Simmons 1998). Indeed, the primary channel for enforcement may lie at the domestic level.

Regime type has featured prominently in studies of the influence of domestic politics on whether governments keep institutional commitments, yet conflicting findings suggest that there is no direct relationship between the two. On the one hand, democracies may be more likely to follow through with commitments because constituents can pressure the government to comply (see for example, Neumayer 2002; Gaubatz 1996; Mansfield et al. 2002; Raustiala and Victor 2004; Tomz 2007). Yet, there are cases in which democracies may be less likely to follow through with commitments than non-democracies (Busch and Reinhardt 2002; Simmons 2000b). Instead, as Dai (2006, 691) points out, “although democratic institutions intensify the degree of electoral accountability, whether this effect leads to a higher level of compliance depends on the political attributes of competing interests” (see also, Dai 2006, 2007). Because domestic constituents may not always favor compliance, democratic leaders must assess and weigh the domestic political consequences when deciding whether or not to follow through with institutional commitments.

Bringing these issues to bear on the IHR and the use of barriers, there is reason to think that domestic political factors, and regime type specifically, might influence a government’s decision about whether or not to abide by commitments to the IHR. Indeed, as the next section describes in more detail, there are domestic benefits and costs associated with imposing barriers during a disease outbreak that an electorally-minded government must consider.Footnote 7 The argument outlined in the next section draws on the general proposition that the influence of democratic institutions on compliance is conditional on other features of the state. In specifying which conditions these are in the case of the IHR, I argue that the quality of domestic health infrastructure helps democratic governments to decide whether imposing barriers is more or less politically beneficial than not doing so.

4 Theory: Barriers as political cover

Building on the premise that domestic political institutions influence compliance behavior, I argue that, as with many types of policy decisions, governments consider the anticipated reaction of domestic groups when selecting policy options for responding to a disease outbreak. And, they will weigh the domestic costs and benefits of imposing barriers against not doing so and following WHO recommendations instead. Governments will choose the policy that is likely to minimize the domestic political costs relative to the benefits. Drawing on this logic, this section explains that whether democracies are likely to follow through with their commitments to the IHR to not impose barriers depends on the state’s ability to effectively respond to the disease outbreak. The following lays out an important assumption underlying the argument, provides a framework for understanding governments’ choice to impose barriers, and then outlines hypotheses based on that framework.

The argument assumes that democratic governments are more dependent on popular support to maintain office and govern effectively than are non-democratic states. This is because, as scholars examining regime type and international cooperation argue, democratic institutions hold governments more accountable to domestic actors than their non-democratic counterparts (e.g., Allee and Huth 2006; Caraway et al. 2012; Dai 2006, 2007; Hafner-Burton et al. 2011; Simmons and Danner 2010). As Allee and Huth (2006, 226) write, “political opposition forces in democratic regimes are better able to challenge the policy programs of governments and to remove leaders from power due to powerful institutions such as frequent competitive elections, durable opposition political parties, and independent legislatures and media.” This perspective is also supported by the comparative politics literature (Dahl 1971; Schumpeter 1942).

Importantly, I do not assume that all democracies are more reliant on popular support than all non-democracies, or that non-democracies are not at all dependent on some sort of domestic support. All governments care to some extent about the reaction of the domestic population. Even non-democracies can be accountable to domestic actors—particularly when they have seemingly democratic institutions like multiparty political systems that allow societal groups to make demands on the government (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006, 2007; Gandhi 2010; Vreeland 2008). But, on average, as the strength of democratic institutions increases, citizens and interest groups have greater political influence on governments, and leaders pay relatively more attention to the public reaction to policy choices. This is why, even though the following discussion sometimes refers to a binary distinction between “democracies” and “non-democracies” for the sake of simplicity, the theory, hypotheses, and empirical analysis conceptualize democracy as a continuous variable. The strength of democratic institutions varies across states; therefore, so does government accountability to the public and the extent to which governments’ political fortunes rely on popular support.

4.1 The decision to impose barriers

Because domestic actors influence the political fortunes of governments, leaders consider the reaction of domestic groups when deciding how to respond to a disease outbreak. As others have shown, leaders prioritize maintaining office and need domestic political support to do so (Geddes 1996; Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). Governments that pursue policies that fail or are unpopular are vulnerable to losing the domestic support that they rely on to stay in power and govern effectively. Importantly, an inadequate response to a disease outbreak can have political consequences for governments. For example, during SARS, the Canadian Prime Minister, Premier of Ontario, and Mayor of Toronto “drew fire from media and opposition party critics accusing them of failing to respond effectively and address public fears” (Institute of Medicine 2004, 255). Similarly, South Korean President Park Geun-hye’s image as a strong leader came “crashing down,” along with her approval rating, amidst criticism over the response to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome that first appeared in the country in May 2015 (Sang-hun 2015). Potential domestic backlash for policy failures in the face of an outbreak means that governments will think carefully about how they respond to disease outbreaks, and will consider how domestic groups are likely to react to different policy choices.

What, then, are the specific domestic costs and benefits associated with the decision to impose barriers during an outbreak? The primary benefit of imposing barriers is to provide leaders with political cover by increasing public confidence in the government’s response. Outbreaks, especially of new strains of disease like H1N1 or SARS, create anxiety in other potentially vulnerable states (Taylor 2013). At the outset, the cause, lethality, mode of transmission, vaccine, and treatment may be unknown. When H1N1 emerged, for example, schools, universities, museums, and other public gathering places were closed in parts of Canada, Mexico, and the US (the first and most highly affected states) to stymie spread, exacerbating fears amongst the populations of other states of what would happen if the outbreak crossed the border. Imposing barriers can make the population feel like it is being protected and provide assurance that the government is doing all that it can, regardless of whether barriers actually prevent disease spread. As such, using barriers provides governments with political cover, protecting them from charges of negligence later if the outbreak enters the country and causes damage.

Governments have good reason to think that imposing barriers might boost public confidence and provide political cover. Opinion surveys show that the public tends to overestimate the likelihood of disease spread and the effectiveness of response measures like barriers (Brahmbhatt and Dutta 2008). Fear and anxiety increase popular support for restrictive policies such as quarantine and other limits on civil liberties (Casey 2015; Gadarian and Albertson 2014). And, there are numerous examples of domestic populations calling for trade and travel barriers during outbreaks, even when WHO recommends against them. In October 2014, even though WHO recommended against a general ban on trade and travel in response to Ebola, around 70 % of the US public wanted the government to impose more restrictive border measures (Washington Post-ABC News 2015), and many members of Congress criticized President Obama for not imposing travel bans (Nyhan 2014; The Economist 2014).

As noted, during the H1N1 pandemic, WHO also recommended against bans on trade and travel. China was one of the 47 states that imposed them anyway. China suspended flights to Mexico, imposed broad quarantine measures, and banned pork imports from H1N1-affected countries. As Huang (2009) writes, the government cared more about creating the impression of “a caring government fully in charge” than it did about launching an evidence-based response that adhered to WHO recommendations. And, the government was rewarded for these actions with a needed legitimacy boost in the days preceding the 20th anniversary of the crackdown in Tiananmen Square: a survey conducted by the China Youth Daily found that 85 % of the public supported the government’s response to H1N1 (Huang 2013, 105). Because public calls for barriers will often materialize at some point during an outbreak, a government that refrains from imposing barriers thus risks being accused of not protecting the population if the outbreak ends up causing widespread sickness or fatalities. So, in providing political cover against these charges, barriers can be politically beneficial for governments.

However, imposing barriers can be associated with various costs as well. Barriers incentivize outbreak concealment in the future, may be an inefficient use of resources that could be used fighting the outbreak in better ways, hinder containing the outbreak at its source by preventing health workers and resources from getting where they need to go, and risk giving the state a bad international reputation. Importantly, barriers can also harm the domestic economy. Certain industry-specific interests lose out from protectionist policies. The travel and tourism industry is an obvious example since travel barriers can directly affect operations. Additionally, during H1N1, initial labeling of the disease as “swine flu” contributed to the misconception that the disease spread through pork. As a result, most states that imposed barriers did so through import bans targeting pork products. Not surprisingly, domestic pork industries—importers in particular—opposed these policies and lobbied governments in a number of states to refrain from imposing import barriers because of the potential economic cost. Therefore, when deciding whether or not to impose trade and travel barriers, a government must weigh the political benefits of imposing barriers, which include providing political cover and protection from being “blamed for ‘failing’ to protect [its] citizens” against the costs of imposing them and potentially harming the domestic economy (quotation from Buthe 2008, 91).

4.2 Health capacity and democratic institutions

How do governments carry out this cost-benefit analysis? Certain governments are more in need of the political cover that barriers offer than others. Governments anticipate relatively higher domestic political benefits for imposing barriers when the state’s ability to respond effectively to the outbreak is in question. When a state has weak health capacity and is ill-equipped to handle an outbreak, substantial time can pass before authorities realize the disease has entered the country. Responses are likely to be delayed and inadequate because states with weak health infrastructure lack the ability to deploy coordinated local and national containment efforts. Many citizens do not have access to health care and these states may not have the ability to correctly diagnose the disease, distribute treatment, follow up with patients after treatment, or reach others that a patient may have exposed to the disease. In short, if the disease enters the country, it is likely to cause damage, and the public will question the state’s ability to protect the population and look for someone to blame. As a result, a state with weak health infrastructure will try to compensate for weak domestic capacity with border measures in an attempt to show that the government is doing something to protect the public.

Alternatively, where health infrastructure is strong, governments anticipate less damage in the case of outbreak spread because they are better positioned to effectively detect and manage it (Scoones 2010; Vu 2011). These governments can communicate more effectively with the population about the outbreak and the state’s response. Importantly, with the appropriate expertise, the government can let the public know about the more effective measures that the state is implementing instead of barriers. These states have better-developed surveillance and laboratory capabilities and will be able to diagnose cases and distribute a treatment more quickly and efficiently than weak health infrastructure states. Consequently, the public will have more confidence in the government’s response. For example, during SARS, the government in Singapore launched a rigorous and successful response, which included effectively identifying and isolating potential cases. As a result, in April 2003 while the outbreak was ongoing, “three out of four Singaporeans were confident that the government could stop SARS” (Institute of Medicine 2004, 256). Where health infrastructure is strong, public fear is likely to dissipate as the state is able to effectively manage the outbreak. Governments in states with strong health infrastructure do not worry as much about being charged with negligence or a loss of political support as those in states with weak health infrastructure. So, states with strong health infrastructure face weaker incentives to impose barriers.

If this political cover logic is at work, the quality of health infrastructure should be particularly important for governments that are especially accountable to voters and interest groups. Because the public’s reaction to policy choices has greater political consequences for governments that are more accountable to domestic actors, the trade-off between being seen as protecting the population and preventing economic harm is especially salient for democratic governments. More so than other states, the level of health infrastructure helps democratic states to assess whether imposing barriers is more or less politically beneficial than not doing so. Democracies with weak health infrastructure are especially dependent on maintaining public support and are not confident that the state will be able to effectively respond to the outbreak if it crosses the border. Therefore, democracies with weak health infrastructure face particularly strong incentives to impose barriers for political cover. These governments need to have a tangible action to point to later as evidence that they did all they could to protect the population. Alternatively, democracies with strong health infrastructure are more confident that they will effectively respond to the outbreak if it ends up affecting the country, and the political benefits of imposing barriers are lower for them relative to the costs of doing so. Therefore, the stronger are democratic institutions, the more weak health infrastructure should encourage governments to impose barriers. This logic leads to the following hypotheses:

-

H1.

States with weak health infrastructure should be more likely to impose barriers than those with strong health infrastructure.

-

H2.

The positive influence of weak health infrastructure on the likelihood of imposing barriers should increase with the strength of democratic institutions.

If states with weak health infrastructure, and especially democracies with weak health infrastructure, are using barriers as political cover, then they should not only be more likely to impose barriers, but they should also do so quickly. Though public calls for barriers are likely to develop, governments do not wait for these demands to materialize and then respond in real time. Instead, these governments proactively impose barriers in anticipation of the public fear and demands for barriers that could develop and hurt them politically later if the outbreak enters the country and the state cannot effectively respond. Other states anticipating lower domestic political costs for not imposing barriers do not feel such pressure and can afford to bide their time to better assess the domestic and international costs and benefits they might face for imposing barriers or refraining from doing so. H1N1 provides an opportunity for examining this mechanism because WHO declared H1N1 a public health emergency and recommended against barriers soon after the outbreak was reported (CDC 2009; Nature 2009), leaving little time for public fear or demands for barriers to materialize in the interim. Therefore, the more quickly a government imposed barriers, the more likely it is that this decision was made for the purposes of political cover rather than in response to public pressures in real time. To evaluate whether this mechanism is operating, I test the following hypotheses:

-

H3.

States with weak health infrastructure should impose barriers more quickly than those with strong health infrastructure.

-

H4.

The positive influence of weak health infrastructure on the speed with which states impose barriers should increase with the strength of democratic institutions.

Having laid out the argument and expectations, the following describes the data and methods and then tests the argument against alternative explanations.

5 Data

To examine the hypothesized relationship between electoral accountability, health capacity, and the imposition of barriers, I assembled an original dataset coding the behavior of the 193 WHO member states during the H1N1 pandemic.Footnote 8

5.1 Dependent variables

I examine two dependent variables.Footnote 9 First, I code a binary variable for whether a state imposed trade or travel restrictions. Since during H1N1, WHO stated that it was “not recommending any trade or travel restrictions,” states that imposed any border measure did not follow these recommendations. Therefore, a state is coded “1” for having imposed barriers if it had any trade or travel restrictions related to H1N1 in place on or after April 27, 2009, the day following WHO’s April 26 recommendation against such barriers.

Three countries imposed barriers before April 27. China and the United Arab Emirates imposed bans on April 26, and Uzbekistan imposed a ban on April 21; all kept the barriers in place following WHO’s announcement and so are coded as having imposed barriers. All other states imposed barriers after WHO issued its recommendations. Following this coding, 47 WHO member states imposed barriers (see Table 1), while 146 followed WHO recommendations.

Of those that imposed barriers, 42 put in place bans on the importation of some combination of live pigs and/or other animals, pork/pork products, and other types of meat products from some or all H1N1-affected states, one state restricted the issuance of visas for Mexican citizens (Singapore), and five states cancelled flights to H1N1-affected states or introduced entry screening not called for by WHO (Argentina, Cuba, China [China also imposed a pork import ban], Peru, and Vietnam). To account for this variation, I code the outcome as an ordinal variable and the findings remain unchanged. I discuss all robustness checks in section 6.3 and fully present the results in the Online Appendix.

Data were gathered from WHO’s H1N1 Situation Reports and WTO’s Trade Monitoring Database. States coded as having imposed barriers by only one of these sources were cross-checked with the United States Trade Representative (2010) “Report on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures” and US government cables sent during the outbreak.Footnote 10

The second dependent variable codes the duration of time in days from April 27, 2009, until a state imposed barriers. In most cases, timing information was available from the above sources. In a minority of cases, newspaper sources were used to gather timing information.

5.2 Main explanatory variables

To measure the quality of domestic health infrastructure I focus on the level of disease outbreak preparedness. Measuring preparedness is difficult because available metrics tend to focus on health spending and are not necessarily a reflection of preparedness, which depends on how money is spent, not just how much. Preparedness requires early warning and surveillance systems, laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, coordination of local and national policy and ability to implement that policy, and also communication systems to provide information to the public, not to mention human and financial resources to support these tasks (World Health Organization 2006, 2009b). The IHR 2005 outline the capacities required for outbreak preparedness but no assessment of these capacities for each state existed at the time of H1N1. For many years though—including in the lead up to the H1N1 pandemic—WHO has classified states according to their capability to diagnose type A influenza virus, which includes H1N1. I use this classification to code a binary variable for health infrastructure. I code the 86 states that were able to diagnose influenza type A virus in humans before the H1N1 outbreak as having strong health infrastructure and the remaining 107 as having weak health infrastructure (World Health Organization 2009c).

Although diagnostic capability does not capture the full range of requirements for outbreak preparedness, it is a necessary condition. Rapid detection is the most effective way to contain an outbreak, and diagnostic capability plays a central role (Snacken et al. 1999). If countries cannot get over the diagnostic hurdle, disease detection will be delayed and perhaps inaccurate, hampering the effectiveness of other response capacities that might exist, including attempts to develop a vaccine and treatment. WHO emphasizes the importance of diagnostic capability for preparedness, noting that the laboratories tasked with diagnosing influenza have been the “backbone of WHO’s Global Influenza Surveillance Network for more than 50 years… [and] have a key role in detecting viruses with pandemic potential, thus facilitating responses to outbreaks and preparedness for pandemics” (World Health Organization 2009d). The importance of diagnostic capabilities was also clear during H1N1. In its assessment of Peru’s response, for example, the US government writes, “while the Peruvian healthcare system has many weaknesses, its biggest challenge with the H1N1 outbreak has been to meet the testing demands” (McKinley 2009). The importance of diagnostic capability for overall outbreak preparedness makes it a good measure for my purposes. Because health infrastructure is a key explanatory variable, however, I use total (private + public) health expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) as a robustness check (World Bank 2016).

Next, to examine the key hypothesis that the influence of health infrastructure should increase as democratic institutions strengthen, I create an interaction term equal to the product of health infrastructure and democracy. I measure the strength of democratic institutions for each state in 2008 (the year prior to the H1N1 outbreak) using the Polity score from the Polity IV data project, which captures the competitiveness and regulation of political participation, the openness and competitiveness of executive recruitment, and constraints on the chief executive, and ranges from −10 (strongly autocratic) to 10 (strongly democratic) (Marshall et al. 2014).

5.3 Alternative explanations and controls

As Section 3 describes, existing approaches in the literature on IOs and compliance can be split into two broad categories: those that focus on international factors and those that focus on domestic level factors. The analysis includes a number of variables to capture these alternatives. All measures are for 2008, the year before the H1N1 outbreak, unless otherwise noted.

Several controls account for the possibility that international costs and benefits drive state behavior. I include measures of GDP, GDP per capita, and military spending as a percentage of GDP, all from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (World Bank 2016). To capture the possibility that variation in vulnerability to US retaliation explains variation in which states impose barriers, I control for dependence on US military and economic aid (USAID 2016), trade dependence on the US (International Monetary Fund 2012), and imports of US pork products as a percentage of GDP (USDA 2015). Because states might also worry about maintaining access to aid, trade, or security benefits generally, I control for the level of trade exposure (World Bank 2016) and whether a state was a WTO member and subject to its dispute resolution mechanism at the time of H1N1 (World Trade Organization 2015). And, since regional partners are often in a position to dole out material or normative punishment, in the duration analysis I control for regional policy diffusion by including a variable that codes for each state the proportion of other states in the region imposing barriers each day of the observation period (lagged by one day).

Turning to domestic level factors, regime type alone could matter—perhaps democracies are more cooperative generally and thus more likely to follow WHO recommendations, regardless of the quality of health infrastructure. I examine the influence of regime type alone with models that do not include the interaction term (Model 1 in Table 2 and Model 4 in Table 3). To account for the possibility that breaking international commitments may be particularly costly for leaders of states with a strong commitment to the rule of law at home (Abbott and Snidal 2000; Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Kelley 2007), I include the Worldwide Governance Indicators’ measure of domestic commitment to the rule of law (Kaufmann et al. 2010).

Furthermore, domestic characteristics other than the quality of health infrastructure might influence the behavior of democratic governments. Therefore, I examine whether the level of democracy interacts with economic inequality (World Bank 2016), the ideology of the ruling political party (Beck et al. 2001), whether the government holds a majority of seats in the legislature (Beck et al. 2001), and whether elections are based on a plurality system or proportional representation (Beck et al. 2001).

Lastly, I include a set of controls particular to this issue area. A binary variable coding whether WHO reported SARS cases in each state accounts for the possibility that past experience influences behavior during H1N1. I include the percentage of GDP made up by pork imports (United Nations 2013) because the more pork products a state imports, the more likely might that state be to impose a barrier on those imports. Additionally, to capture perceptions of vulnerability to disease spread, I include a measure of whether the state is highly embedded in the air traffic network because disease spread often follows travel patterns (Tatem et al. 2006). Finally, states might also feel more vulnerable to the disease as it spreads across the globe. In the duration analysis I include a variable that codes for each state the proportion of other states in the region reporting cases of H1N1 each day of the observation period (lagged by one day).

6 Methods and results

I use several statistical models to test my argument against these alternatives. Because the first dependent variable is binary, the primary analysis uses logistic regression to evaluate whether weak health infrastructure increases the likelihood of imposing barriers, and most importantly, whether health infrastructure interacts with democracy to influence variation in the imposition of barriers across the 193 WHO member states. I then investigate whether weak health infrastructure interacts with democracy to increase the speed with which states impose barriers. Here I use a set of Cox proportional hazard models to explain the duration of time in days between WHO recommendations against trade and travel barriers and states’ imposition of barriers. Because a small percentage of the cells in the data contain no information, I use multiple imputation to account for missing data in all models except for Model 7, the duration model using time-series cross-sectional data (King et al. 2001).Footnote 11

The logit model takes the following form:

where Logit(Barriers) i denotes the logit function of the likelihood that country i imposes barriers, W is a vector of control variables, and ∈ i is the error term.

The Cox model takes the following form:

Where h i (t) is the probability of country i imposing barriers conditional on having not imposed barriers until time t, h o (t) represents the baseline hazard of imposing barriers, and Z is a vector of control variables (for further details see Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). I use the Cox model because I do not have a strong expectation about the shape of the survival curve. In contrast to parametric duration models like the exponential or the Weibull models, the Cox model is semi-parametric—it does not make an assumption about the shape of the baseline hazard (Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn 2001).

6.1 Imposing barriers during H1N1

Table 2 displays the results of three logit models. The first examines whether the quality of health infrastructure alone affects the imposition of barriers (H1), the second includes an interaction term to evaluate the hypothesis that the magnitude of the effect of health infrastructure should be greater as democratic institutions strengthen and governments become increasingly reliant on maintaining public support (H2), and the third demonstrates that the findings are robust to alternative explanations.Footnote 12

The results provide compelling evidence that governments impose barriers to avoid domestic political costs. Model 1 shows that, all else equal, states with strong health infrastructure are less likely to impose barriers than states with weak health infrastructure. Importantly, however, Model 2 provides support for the argument’s key expectation—that the effect of the quality of health infrastructure is conditional on the level of democracy. Indeed, there is a significant negative interaction between the quality of health infrastructure and democracy—health infrastructure has the strongest influence in electorally accountable states where governments are especially reliant on maintaining popular support. The statistical and substantive significance of interaction terms and logit coefficients cannot be interpreted directly. Therefore, Fig. 1 presents first differences in the simulated predicted probability of imposing barriers moving from states with strong to weak health infrastructure as democratic institutions strengthen.Footnote 13 At each level of Democracy from −10 to 10, the figure shows how much more (or less) likely a state with weak health infrastructure is to impose barriers than one with strong health infrastructure.

The figure illustrates that democracies with weak health infrastructure are significantly more likely to impose barriers than are democracies with strong health infrastructure. The substantive impact is quite large: the figure shows that when Democracy (the Polity score) equals 7, a state with weak health infrastructure is 28 percentage points more likely to impose barriers than a state with strong health infrastructure. For example, El Salvador, which has a Polity score of 7 and weak health infrastructure, has a 38 % likelihood of imposing barriers, whereas a similarly democratic state like Colombia, which has relatively strong health infrastructure, only has a 10 % likelihood of doing so.

In fact, the figure shows that health infrastructure only influences the likelihood of imposing barriers for states that have a Polity score of 4 and above. And, for those states, as the level of democracy increases, the influence of health infrastructure increases in magnitude as well. For example, when the Polity score equals 4, having weak health infrastructure increases the likelihood of imposing barriers by 20 percentage points, whereas when the Polity score equals 8, weak health infrastructure increases the likelihood of imposing barriers by 31 percentage points. The finding that the effect of health infrastructure is greater in states that are on average more accountable to domestic actors and thus more sensitive to the public’s reaction lends further support to the claim that health infrastructure operates primarily by influencing the domestic political benefits of imposing barriers.

Another intriguing finding further illustrates that democratic states are not always more cooperative than others. As Model 1 shows, regime type alone is not significantly associated with imposing barriers; instead, its effect is conditional on the quality of health infrastructure. Figure 2 presents the marginal effect of moving from a non-democracy (Polity score of −6) to a democracy (Polity score of 7) on the likelihood of imposing barriers for states with strong (the point on the left) and weak health infrastructure (the point on the right). Though among strong health infrastructure states, a democratic state is 24 percentage points less likely to impose barriers than a non-democracy, among states with weak health infrastructure this difference is no longer significant and the direction of the effect is actually positive. Consistent with Dai (2006), electoral accountability only sometimes leads to cooperation. When democracies have weak health infrastructure they are no longer more likely than non-democracies to cooperate by following WHO recommendations and not imposing barriers during an outbreak.

Lastly, Table 2 also shows that these results are robust to the inclusion of alternative explanations. In addition to the finding that democracy alone is not associated with the imposition of barriers, there is limited evidence that international factors drive variation in state behavior. Though GDP per capita and economic size are positively associated with imposing barriers, military spending, trade exposure, and WTO membership are not statistically significant. Similarly, vulnerability to US retaliation does not discourage states from imposing barriers. US trade dependence and the share of GDP made up by US economic aid are not significantly associated with state behavior, and though the coefficient on the share of GDP made up by US military aid is significant, the direction of the effect is the opposite of what was expected—instead of discouraging states from imposing barriers, the more US military aid a state receives, the more likely it is to impose barriers. As expected, commitment to domestic rule of law is negatively associated with imposing barriers—in other words, positively associated with following WHO recommendations. And, having higher pork imports is positively associated with imposing barriers. Neither having had SARS cases nor being highly embedded in the air traffic network are significant factors.

Finally, in the Online Appendix, I show that the share of GDP made up by US pork imports is not significantly associated with state behavior. The Online Appendix also reports that several other domestic level factors do not interact with the strength of democratic institutions to affect the likelihood of barriers. Economic inequality, the ideology of the government, whether the government’s party holds a majority of seats in the legislature, and whether elections are based on plurality or proportional representation do not significantly influence the behavior of democracies (the interaction term between each and the Polity score is not statistically significant). In terms of their influence alone, only economic inequality (measured with the gini coefficient) is significantly associated with barriers. Where inequality is higher, a government is less likely to impose barriers. But, including the gini coefficient as an additional control does not change the substantive findings about the conditional effect of health infrastructure and democracy on barriers.

6.2 The timing of barriers

As explained in Section 4, if states that impose barriers are doing so for political cover, then these states should impose barriers quickly to send a signal to the public that they are acting ahead of the crisis and doing something to prevent disease spread. I use a set of Cox proportional hazard models to examine the speed with which states impose barriers.

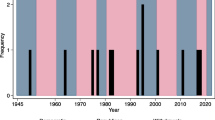

Table 3 displays the results of the hazard models.Footnote 14 The results are reported as hazard rates, which indicate the impact of a given variable on the rate of imposing barriers relative to a baseline “hazard” of 1.00. Coefficients greater than one proportionately increase the rate while coefficients less than one proportionately reduce the rate. Models 4, 5, and 6 examine variation across the 193 WHO member states. To examine the effect of the two time-varying covariates—regional policy diffusion and disease spread patterns—Model 7 uses time-series cross-sectional data with the country-day as the unit of analysis.Footnote 15 For all four models, the observation period begins on April 27, the day after WHO recommended against trade and travel barriers, and lasts through day 56, the day after H1N1 was reported on all seven continents.Footnote 16

The evidence further supports the argument. Model 4 shows that health infrastructure alone is actually not associated with the timing of barriers. Instead, as Models 5–7 show, its effect on timing is conditional on the level of democracy. Weak health infrastructure only increases the speed with which states impose barriers in democracies where the government is especially concerned with maintaining domestic political support. This finding supports the contention that these states impose barriers proactively in anticipation of a negative public reaction later if the outbreak enters the country.

For ease of interpretation, Fig. 3 presents the conditional relationship between health infrastructure and democracy visually. The figure presents the ratio of the hazard rates of imposing barriers of states with weak health infrastructure to those with strong health infrastructure as democratic institutions strengthen.Footnote 17 Each point represents how much more likely a state with weak health infrastructure is to impose barriers on any given day of the outbreak than a state with strong health infrastructure at the given level of democracy. In states with Polity scores greater than 2, weak health infrastructure increases the rate of imposing barriers, but it does not have a significant effect in less democratic states. The substantive impact is large: for example, the figure shows that when the Polity score equals 7, states with weak health infrastructure are 5.1 times more likely to impose barriers on any given day of the outbreak than their counterparts with strong health infrastructure. In other words, among democratic states, those with weak health infrastructure impose barriers more quickly than those with strong health infrastructure.

Results also show that the findings are robust to alternative explanations. Model 4 shows that, again, democracy alone is not a significant predictor of state behavior. Domestic commitment to the rule of law is associated with a decrease in the rate of the imposition of barriers in Models 4–7. GDP per capita is associated with an increase in the hazard rate in Models 5 and 6, and economic size is correlated with an increase in the rate of the imposition of barriers in Models 4–6. Being highly embedded in the air traffic network (Model 6) and trade exposure (Model 7) are associated with an increase in the rate of the imposition of barriers in one of the models, but none of the other control variables are significant, including regional policy diffusion and regional disease spread patterns.

In summary, the findings are consistent with the argument that governments impose barriers as political cover. The cases of Jordan and Colombia illustrate this dynamic. Jordan, which has weak health infrastructure, imposed a pork import ban in response to H1N1 that was aimed at insulating the government from criticism rather than protecting the population from the outbreak. Jordanian imports of US pork products in the year prior to H1N1 were negligible and consisted only of frozen or heat-treated rather than fresh products. Yet, in early May 2009, the country imposed an import ban on only fresh pork products and not on frozen or heat-treated products from the US and publicized the ban in the Jordanian press. Not only did Jordan make the bans public, but the government ensured that these barriers would not actually impact the pork product imports coming from the US (as trivial as they were). This suggests that the action was a political maneuver and corroborates statements by the Assistant Secretary General for Animal Welfare from Jordan’s Ministry of Agriculture that the ban was “a precaution” because of “public pressure and fear” (Beecroft 2009a, b).

Alternatively, Colombia, a democracy (Polity score equals 7) with strong health infrastructure was considering a pork imports ban at the beginning of the H1N1 outbreak (Johnson 2009, 6). But, the government ultimately decided against a ban, citing pressure from the Colombian pork industry, which was worried about the negative economic repercussions of barriers (Brownfield 2009). Statistical analysis presented in the Online Appendix shows that the dynamics of the Colombia case can be generalized—democracies with strong health infrastructure are even less likely to impose barriers when they have high pork imports. Indeed, democracies with strong health infrastructure still consider the reaction of domestic actors when deciding whether to impose barriers, but because they are more confident in the state’s ability to respond to the outbreak, these states can pay attention to the costs of imposing barriers, including harm to domestic economic interests.

6.3 Alternative explanations and robustness checks

The empirical analysis is consistent with the argument laid out in Section 4 that some states use barriers as political cover. But, beyond the alternative explanations drawn from the compliance literature (see Section 3) that I control for in the empirical analysis, some other alternative mechanisms particular to this case are worth addressing. First, though WHO’s position is that barriers rarely protect from disease spread (and there is substantial evidence in support of that claim), does it matter whether or not governments believe that barriers work? In short, no.

To begin with, whether or not states believe WHO that barriers do not protect against disease, the variation in state behavior that we see is a puzzle. If states believe that barriers do not work, then why do some states use them? If, on the other hand, states think barriers do work, then how come many states do not use them? Indeed, a key reason why states agreed to follow WHO guidance under the revised IHR is because they wanted WHO, which has access to the requisite technical expertise, to determine whether barriers will be effective in a given case.

Furthermore, the key finding that the influence of weak health infrastructure on the likelihood and speed of imposing barriers increases as democratic institutions strengthen supports the domestic political logic that I put forward, regardless of states’ beliefs about the effectiveness of barriers. Whether or not states believe that barriers offer protection, what changes as democratic institutions grow stronger are the domestic political incentives that governments face, which is the core of the political cover argument presented here.

A second alternative explanation looks to the role of protectionist pressures in government decision making. Is it possible that traditionally protectionist import-competing groups such as those that produce pork for domestic consumption pushed for import barriers under the guise of the threat of H1N1? For one thing, the preferences of these domestic interests during a disease outbreak are not straightforward. As H1N1 and other outbreaks illustrate, consumers tend to seek substitutes for the supposedly affected products even in markets that are not affected by the outbreak, which leads to decreased demand across the board (Blayney 2005; Moore and Morgan 2006, 6). As such, even traditionally protectionist groups may be against imposing barriers during outbreaks. Furthermore, consumers avoid the supposedly affected product whether or not it is produced domestically or imported; consumers do not simply switch to domestic producers of the product. Therefore, in these cases, protection is not likely to yield financial gains for domestic producers.

In short, the potential economic costs of imposing barriers during outbreaks may unify industry-specific interests against barriers that are divided in “normal” times. Still, the Online Appendix includes models that control for the level of domestic livestock production as a proxy for protectionist pressures and I find no relationship with the imposition of barriers (see Table A9 in the Online Appendix).

I also undertake several tests to ensure the robustness of the empirical results, which are all fully reported in the Online Appendix. I pre-process the data by matching on health infrastructure to help correct for the reality that “treatment” and “control” groups differ on factors other than the variable of interest (Ho et al. 2007). And, because states imposed different types of barriers including trade barriers, travel barriers, or both, I code the outcome as an ordinal variable, coding a state as “1” for not imposing barriers (146 states), “2” for imposing only travel barriers (5 states), and “3” for imposing either only trade barriers or both trade and travel barriers (42 states, with China being the only state to impose both trade and travel barriers). Neither the matching procedure nor the ordinal coding changes the substantive findings (see Tables A5, A11, and A12 in the Online Appendix).

I also use alternative measures for the two key explanatory variables—democracy and health infrastructure. Using the Political Competition Concept variable from the Polity IV dataset, which captures how the population participates in the political system by identifying “ten broad patterns of political competition scaled to roughly correspond with the degree of ‘democraticness’ of political competition within the polity” (Marshall et al. 2014), as an alternative measure for democracy does not change the substantive results (see Table A2 in the Online Appendix).

Using health spending as a percentage of GDP as an alternative measure of health infrastructure does not alter the central findings, either (World Bank 2016). Consistent with the analysis presented above that uses diagnostic capability as a measure of health infrastructure, high health spending reduces the likelihood of imposing barriers in democracies while low health spending encourages democracies to impose barriers (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix). Interestingly, however, for less democratic and non-democratic states (with Polity scores below -1), health spending actually has a significant positive effect on the likelihood of imposing barriers. In contrast, the empirical analysis presented above finds no significant association between health infrastructure and imposing barriers for states with Polity scores below 4. As previously discussed, health spending is not a good measure of health infrastructure for the purposes of this study, thus, it is not surprising that results differ slightly. Still, future work should investigate the possibility that health infrastructure influences the behavior of democracies and non-democracies through different causal processes. Lastly, including health spending as an additional regressor in Models 1–3 (rather than in place of diagnostic capability) does not change the key findings, either (see Table A4 in the Online Appendix).

In sum, empirical findings cast doubt on several alternative mechanisms, and the article’s core findings are robust to alternative model specifications, an alternative coding strategy for the dependent variable, and the use of alternative measures for the key explanatory variables.

7 Conclusion

In spite of the growing frequency of disease outbreaks, including several high profile events like the 2003 outbreak of SARS, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and more recently, the 2014 outbreak of Ebola, little attention has been paid to how states respond to these crises, or whether and why they follow through with commitments to the IHR to abide by WHO guidance during outbreaks. As such, this article has examined a central challenge to successful outbreak response—the continued use of trade and travel barriers.

The argument and findings presented here show that domestic politics plays a central role in why states impose barriers. For some states, a desire for domestic political cover outweighs commitments to the IHR and undermines international cooperation during global health emergencies. The quality of domestic health infrastructure helps democratic governments to weigh the political costs and benefits of imposing barriers against following WHO guidance and abiding by commitments to the IHR. And, the empirical analysis shows that democratic governments are more likely to impose barriers, against the advice of WHO and to the detriment of global outbreak preparedness, when these states have weak health infrastructure and lack confidence in their ability to respond to the outbreak if it crosses the border.

The study has implications for several areas of scholarship and for the operation of the IHR. First, the IO scholarship has largely overlooked global health issues. This article demonstrates that state behavior during disease outbreaks can offer insight into the dynamics of international cooperation including the issues of credible commitments and compliance that are so well-studied in other contexts (e.g., Fearon 1995, 1998; Simmons and Danner 2010; see also, Simmons 2010).

Importantly, because states could anticipate real international costs in the form of retaliation from the US for imposing barriers, the case of H1N1 posed a hard test for the effect of domestic politics. In showing that domestic level factors drove states to impose barriers even under these conditions, the study’s findings corroborate and strengthen work showing that domestic politics rather than international factors can influence whether states fulfill institutional commitments (Hafner-Burton et al. 2011; Kelley 2007; Simmons 2009; see also, Martin and Simmons 1998).

More specifically, by shedding light on the conditions under which democratic governments are more likely to impose barriers during disease outbreaks, the findings presented here complement and build on existing research on whether, and how, democratic institutions encourage, or in this case, discourage, cooperation. Importantly, examining the timing of compliance behavior as this article does in the case of the IHR can further probe the mechanisms through which public pressures affect government decision making in other contexts as well.

Finally, the study’s findings have implications for those working to make the IHR more effective. Since domestic level factors played a primary role during H1N1 even when international costs loomed large, reducing domestic incentives to impose barriers will likely be more effective for changing state behavior than trying to increase international enforcement. The argument and findings presented here point to two such strategies: enhancing health capacity and highlighting the ex-post domestic economic costs of trade and travel barriers.

Since health infrastructure influences leaders’ domestic political calculations about whether to impose barriers, improving health capacity can discourage the use of barriers by allowing governments—especially democracies—to worry less about the political costs of outbreak damage and public fear. States wanting to limit the use of barriers during outbreaks and enhance IHR effectiveness should consider increasing contributions to the currently under-funded health capacity development component of the IHR (Fischer and Katz 2013).

Further, highlighting the ex-post costs of imposing barriers is another way to increase the credibility of state commitments to follow WHO recommendations. Legalizing international agreements is one way to highlight these costs because it can make the distributional implications of behavior more transparent (Goldstein and Martin 2000). The revised and legalized IHR make this increased transparency possible. WHO has taken advantage of its authority to issue recommendations in real-time during outbreaks, which makes it easier to tell when states do not follow these recommendations. But, WHO has been hesitant to “name and shame” states when they ignore the organization’s guidance (World Health Organization 2011).

Given its continued reliance on member states for funding, it is not surprising that WHO has been reluctant to publicize states’ disregard of its recommendations. The 2014 outbreak of Ebola provides the most recent example of this tendency on the part of WHO (World Health Organization 2015, 4). Though many states restricted travel in response to the outbreak, acting against WHO recommendations to not do so, the institution did not call states out for this behavior. But, states themselves can point to WHO recommendations against trade and travel barriers to “name and shame” those states that impose barriers anyway (see Kono 2007, 746). Rather than raising international costs, this “naming and shaming” is most likely to change state behavior by highlighting ex-post domestic economic costs and mobilizing domestic groups that lose out from barriers to pressure their governments to abide by WHO recommendations. The pork imports industry may have played just such a role in some states during H1N1 (see the earlier discussion of Colombia as an example).

The argument and findings presented in this article suggest that changing state behavior will require altering domestic political incentives in ways similar to those just outlined. The alternative is the continued use of barriers during outbreaks even when WHO recommends against them, which will continue to incentivize outbreak concealment and hinder outbreak response efforts.

Notes

Evidence supports WHO’s position that barriers are rarely effective (e.g., Bell and World Health Organization Working Group on Prevention of International and Community Transmission of SARS 2004; Colizza et al. 2007; Cooper et al. 2006; Cowling et al. 2010; Ferguson et al. 2006; Poletto et al. 2014; Selvey et al. 2015; Vincent et al. 2009).

Some states lack surveillance capacity and do not know that an outbreak is occurring. Not surprisingly, adequate surveillance capacity is a necessary condition for rapid outbreak reporting. The point here is that the more insidious barrier to reporting is that even when states are fully aware of an outbreak they purposefully conceal it to avoid economic costs. For evidence that this commitment problem is operating, see Worsnop (2016).

In her study of state commitments to the International Criminal Court (ICC), Kelley (2007) makes a similar point. One of the ICC’s central aims was to “assure delivery of indicted suspects to the Court,” and so examining variation in which states signed a non-surrender agreement with the US offered a good test of states’ commitments to the institution because such agreements clearly undermined the ICC’s purpose (Kelley 2007, 574).

During H1N1, the Food and Agriculture Organization, World Organization for Animal Health, and World Trade Organization (WTO) agreed with WHO that barriers would not prevent H1N1 spread (World Trade Organization 2009). Even when WHO has issued travel advisories warning against travel to certain areas because of disease, SARS being the most notable example, states often impose measures that are more restrictive than WHO guidelines.

Furthermore, domestic politics has been shown to be a key determinant of state behavior during domestic crises. Studies of derogations from human rights treaties and human rights violations during states of emergency are instructive on this count, showing that domestic political factors and regime type affect whether and how states uphold commitments to these treaties when they face the hard test of a crisis such as an armed conflict, economic shock, or natural disaster (e.g., Hafner-Burton et al. 2011; Neumayer 2013). With the potential to threaten the health of the population, economic productivity, and social stability, a major outbreak may be viewed as a potential crisis; and as such, governments may be particularly likely to base their response on domestic political incentives.

Note that Holy See was also a party to the IHR at the time of H1N1, but is not included in the analysis; its exclusion does not affect the findings.

Complete descriptions of variable measurement and tables of summary statistics can be found in the Online Appendix, which is available at this journal's webpage.

“WHO H1N1 Situation Reports” available at http://gis.emro.who.int/, WTO “Trade Monitoring Database” available at http://tmdb.wto.org/, USTR report available at http://www.ustr.gov/sites/default/files/SPS%20Report%20Final(2).pdf, and US government cables available at http://www.wikileaks.org.

Imputation is not compatible with clustering standard errors. Because clustering is particularly likely in time-series cross-sectional data, I use listwise deletion for Model 7 and cluster standard errors by country. To account for potential clustering in the other models, the Online Appendix presents results for the following: Models 1 through 3 using a generalized estimation equation (GEE) that allows for dependence within regional clusters (Zorn 2001) and Models 4, 5, and 6 using listwise deletion and clustering standard errors by country (see Tables A6 and A10).

Akaike information criterion for Table 2 models: Model 1: 193.78, Model 2: 187.38, Model 3: 169. The likelihood ratio (LR) test statistic also shows that adding the interaction term in Model 2, and then additional controls in Model 3, improves fit. To calculate the LR test statistic here and for Models 4–6 below, I re-run all models using listwise deletion (see Tables A6 and A10 in the Online Appendix). Comparing Models 1 and 2, the LR test statistic is 8.67, p < .01. For Models 2 and 3, the LR test statistic is, 31.85, p < .001.

N = 190 for Models 4, 5, and 6. Three observations are dropped because timing information was not available.

Akaike information criterion for Table 3 models: Model 4: 433.94, Model 5: 427.64, Model 6: 413.02, and Model 7: 311.76 (note that because Model 7 uses different data it cannot be directly compared to the others). And again, the LR test statistic also shows that adding the interaction term in Model 4, and then additional controls in Model 5, improves fit. Comparing Models 4 and 5, the LR test statistic is 9.68, p < .01. For Models 5 and 6, the LR test statistic is 23.54, p < .01.

Results are insensitive to different length observation periods.

Figure 3 is based on Model 5.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization, 54(3), 421–456.

Allee, T. L., & Huth, P. K. (2006). Legitimizing dispute settlement: International legal rulings as domestic political cover. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 219.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: the database of political institutions. The World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Beecroft, A. R. (2009a). Demarche delivered on removal of Jordanian trade bans on pork due to H1N1. WikiLeaks. WikiLeaks cable: 09AMMAN1058_a. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09AMMAN1058_a.html. Accessed 4 March 2014.

Beecroft, A. R. (2009b). Jordan to lift trade ban on pork. WikiLeaks. WikiLeaks cable: 09AMMAN1418_a. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09AMMAN1418_a.html. Accessed 4 March 2014.

Bell, D. M., & World Health Organization Working Group on Prevention of International and Community Transmission of SARS. (2004). Public health interventions and SARS spread, 2003. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(11), 1900–1906.

Blayney, D. P. (2005). Disease-related trade restrictions shaped animal product markets in 2004 and stamp imprints on 2005 forecasts. Washington, D.C.: USDA, Economic Research Service. http://iatp.org/files/258_2_76146.pdf. Accessed 21 December 2014.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Jones, B. S. (2004). Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Zorn, C. J. W. (2001). Duration models and proportional hazards in political science. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 972–988.