Abstract

Have IMF lending programs undermined political democracy in borrowing countries? Building on the extensive literature on conditional lending, we outline several pathways through which IMF program participation might affect the levels of democracy in borrowing countries - including a new variant that suggests the possibility of a positive association between lending program participation and democracy scores. In order to test the argument we assemble annual data from 120 low- and middle-income countries observed (at maximum) in each year between 1971 and 2007. We use three strategies - genetic matching, instrumental variables, and difference-in-differences estimation - to better estimate the direction and size of the statistical association between participation in IMF lending programs and the level of democracy. We find evidence for modest but definitively positive conditional differences in the democracy scores of participating and non-participating countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Between the mid-1970s, when the IMF signed sizeable (but non-conditional) agreements with the UK and Italy, and 2008, when the financial crisis forced Iceland to turn to the Fund, no historically rich Northern democracies entered into conditional IMF lending programs. After the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, several rich European countries entered into IMF arrangements (in addition to Iceland, three Eurozone members – Greece, Ireland, and Portugal – signed IMF agreements). The crisis also prompted organizational changes, including a doubling of the “exceptional access” threshold (from 300 to 600 percent of quota), the creation of new low-conditionality/high access facilities, and a general “streamlining” of policy conditionality. Because of these changes, we limit the analysis in this article to the pre-2008 period.

Though statistical evidence on the contribution of IMF lending arrangements to government instability is inconclusive. Dreher and Gassebner (2012) examine the determinants of serious government crises in 132 countries (1980–2002); they find that the positive partial correlation between the presence of the IMF and crises disappears after correcting for the endogeneity of lending arrangements. Recent work by Casper (2015), on the other hand, finds a positive relationship between participation in IMF programs and the risk of coups d’état.

Historically, the modal IMF adjustment program has been set up to deal with a crisis springing from an imbalance in the current account – in Ghosh et al.’s (2008) record of 236 IMF programs (1972–2005), for example, just 16 were set up to deal primarily with capital account crises.

One study by IMF researchers suggests, “IMF-supported programs have a statistically significant effect on the share of spending allocated to education and health” (Clements et al. 2011, 14). Rickard (2012) found evidence (from a sample of 44 developing countries, 1981–97) for a robust positive association between IMF programs and welfare spending; in her words, “an optimistic interpretation of this result might be that governments protect social welfare spending from IMF-induced cuts relative to other budget items” (2012, 1181).

Albertus and Menaldo, working with a global sample (1950–2002), find “that an increased coercive capacity under autocracy has a strong negative impact on both a country's level of democracy as well as the likelihood of democratization if the country is autocratic” (2012, 166). While autocrats may use irregular, non-military security forces to repress political competition and dissent, the mechanism we sketch in this section of the article builds on work that explicitly links IMF program participation to reduced military spending in autocratic countries. In focusing on the military as the primary coercive apparatus through which incumbent autocrats fend off potential competitors, we follow Albertus and Menaldo, who argue that “the military is a good proxy for internal repression…the size of the military reflects both the ability to mete out repression against citizens and the opposition as well as the result of organizational proliferation to undermine threats from within the regime” (2012, 153–54). Albertus and Menaldo show empirically that military size is strongly correlated with domestic security spending.

Our presentation of matching in this section is drawn from the lucid description presented by Diamond and Sekhon (2013).

It should be noted that some, like Simmons and Hopkins (2005), disagree with the claim that factors such as “commitment” or “political will” cannot be observed and measured.

Moreover, two of the three studies looked only at a subset of “structural adjustment” programs offered by the IMF.

Not all countries in the sample are observed for the full 36-year window; some observations are excluded due to missing data and several countries did not become independent until later years in the observation window.

Scholars working with different conceptualizations might, for example, consider how IMF programs narrow borrowers’ “policy space” and shift the locus of economic policymaking authority to unelected technocrats.

We chose not to use dichotomous indicators of the presence or absence of democracy (e.g., Alvarez, Cheibub, Limongi, and Przeworski 1996; Gasiorowski 1995) because our approach focuses on how IMF program participation is related to incremental changes in countries’ levels of democracy, rather than looking at the covariates of infrequent (but more fundamental) transitions between regime types. Our approach follows Kersting and Kilby, who (in an empirical analysis of the impact of foreign aid inflows on democracy scores) conceptualize “democratization as a process which is captured by increases in a polychotomous regime measure such as the Freedom House ratings or the Polity index” (2014, 128).

The IMF has, since the early 1970s, provided a number of conditional lending facilities: the Standby Arrangement (SBA), Extended Fund Facility (EFF), Structural Adjustment Fund (SAF), Enhanced Structural Adjustment Fund (ESAF), and Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF). The SBA and EFF programs are non-concessional loans. The first concessional loans (SAFs) were offered to the institution’s least developed countries starting in 1986. In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, the IMF set up several new lending facilities; the Extended Credit Facility (ECF) replaced the PRGF (which superseded the ESAF) in 2010.

The MONA database includes most programs approved by the IMF from 2002 to the present. The database is available here: < http://www.imf.org/external/np/pdr/mona/index.aspx>. We also obtained loan request documents from the IMF’s online archive, which can be accessed here: <http://www.imf.org/external/adlib_IS4/default.aspx>.

The online supplementary appendices are available, along with replication data files, on RIO’s website.

IMF programs also vary in relative generosity (the amount of the disbursement relative to the size of the borrower’s economy) and the extensiveness of conditionality. Some scholars have looked at variation across types of programs; Birchler et al. (forthcoming), for example, distinguish IMF and World Bank loans by three types (“traditional,” structural adjustment, and poverty reduction-oriented programs that date only from the late-1990s) and look at the effect of each type on democratization. See Brown (2009), Limpach and Michaelowa (2010), and Eriksen and De Soysa (2009) for other approaches that disaggregate different aspects of IMF loans (by different types of arrangement and net flows of resources). Measuring the annual flow of IMF credits, as in Eriksen and de Soysa (2009), is not the appropriate indicator for the question we are interested in, which is the conditional difference in the level of democracy between countries under IMF programs and countries without IMF loans. Countries can make payments to the Fund years after they were last under an active arrangement; Argentina, for example, paid back their remaining $9.5 billion credit in 2006, three years after it had last been involved in a lending arrangement with the institution. One would not want to infer from the flow of funds from Argentina to the IMF in 2006 that Fund conditionality had an impact on the Kirchner government’s economic policy choices (or the country’s democracy level).

In Conway’s dataset (covering 105 countries between 1974 and 2003), the modal decile (in terms of the proportion of years that countries in the sample were under IMF arrangements) “was characterized by between 60 % and 70 % of the total period spent in IMF programs” (2007, 207).

Indeed, monarchic and military autocracies are more autocratic than civilian-led dictatorships. The average Polity2 score for civilian autocracies in our sample of countries is −2.03, which is significantly higher than the average for military regimes (−5.63, difference of means is significant at p = 0.0000, t [17.65, 1488.54d.f.]) and higher than the average for monarchic dictatorships (−8.22, p = 0.0000, t [26.02, 1088.55d.f.]). We find very similar differences in the transformed Freedom House scores for military, monarchic, and civilian autocracies.

The oil producer variable for the years between 1970 and 2000 is drawn from Fearon and Laitin (2003); it takes a value of one if oil accounts for greater than one-third of a country’s annual exports. Following Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008), we use membership in OPEC and the IMF’s oil exporter classifications, reported in the World Economic Outlook, to code the post-2000 observations.

See the “Matching” package for R, available at http://sekhon.berkeley.edu/matching/.

Mahalonobis distance, as described by Diamond and Sekhon (2013, 934), is a quantity that measures the distance between the X covariates for units i and \( j:\sqrt{{\left({X}_i-{X}_j\right)}^T{S}^{-1}\left({X}_i-{X}_j\right)} \), where S is the sample covariance matrix of X (containing the observed confounding variables) and X T is the matrix’s transpose. Covariate balance can then be assessed through a variety measures, including t-tests for difference in means and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for equality of distributions.

Replacement means that units can be used to create matches more than once. We also tried one-to-one matching without replacement; the baseline results were not significantly affected by the choice of matching with or without replacement. We further tried other matching procedures, including a more conventional nearest neighbor matching technique. We did not find different types of matching routines significantly modified the core findings we report in the article. The results from other matching routines are reported in Appendix D in the supporting information.

The standardized mean difference is calculated as 100 times the mean difference between treatment and control units divided by the standard deviation of the treatment observations. There is as yet no agreed upon set of best practices for assessing covariate balance, so we examined several other measures of balance, which revealed similar patterns to those reported in Figures 1 and 2. Results are available from the authors upon request.

The pre-matching average for the “treated” units under IMF arrangements was two years later than the average for the untreated units.

The improvement in covariate balance ranged from a minimum of 60.8 percent for the postcommunist region dummy to 100 percent for several covariates.

The difference in means of the post-matched observations indicates that the treatment cases under IMF programs have, on average, slightly higher Polity scores (0.58) than the paired control cases (0.23), though the quarter-point difference in means is not statistically significant (p = 0.13, t (−1.5014, 3241.81d.f.).

For comparison we report results from the regression analysis on the data that have not been pre-processed by the matching procedure in Supplementary Appendix J.

Although we included an extensive set of covariates in the analysis, the reliability of any estimates drawn from matching rests on the assumption that treatment assignment is captured by the observables. While this assumption cannot be directly tested, we also performed a sensitivity analysis based on the recommendations of Rosenbaum (2010: 76–79) using the R package rbounds (Keele n.d.). Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis estimates the amount by which an unobserved confounder would need to alter the odds (denoted by Γ) of receiving the treatment compared to the control in order to negate the estimated effect of the treatment (in this article, IMF program participation). The results suggest the estimated effect of involvement in an IMF program on a country’s level of democracy is unchanged up to a Γ value of 1.3 for the Freedom House measure, and 1.2 for the Polity2 measure. Put differently, an unobservable confounder would need to change the odds of entering an IMF program by a factor of 1.3 (1.2) to overturn the effect of IMF program participation on the transformed Freedom House measure (Polity2 score).

Exceptions include the positive and significant partial correlations between democracy scores and the indicators of a history of previous transitions, the presence of currency crises for democracy levels, and the relative size of international reserve holdings.

Though it should be noted that neither indicator was statistically significant in Oberdabernig's (2013) models of IMF program participation.

We identified 18 country-year observations in which the country participated in both concessional and non-concessional programs in that year (because the country either signed two different programs simultaneously or immediately signed a concessional loan following the expiration or cancellation of a non-concessional loan). We record these observations as episodes of concessional program participation.

For a discussion, see Clemens et al. (2012).

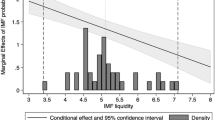

Regression results show that the debt-weighted foreign interest rate indicator was a significant predictor of countries’ likelihood of participating in IMF programs (see Supplementary Appendix I).

In Supplementary Appendix I we describe tests that we ran using two other possible instruments suggested by the extensive literature on the effects of IMF program participation: temporary membership on the UN Security Council (Dreher et al. 2015) and the UNGA “ideal point” indicator of countries’ foreign policy preferences (Bailey et al. 2015). In the online appendix we discuss in greater detail why we rejected the validity of these other candidates, given this study’s focus on the IMF program-democracy score link.

Even though the endogenous variable (IMF Program Participation) is dichotomous, we follow Angrist and Pischke’s (2009: 197–98) pragmatic advice and estimate 2SLS models (see also the discussion here: < http://www.mostlyharmlesseconometrics.com/2009/07/is-2sls-really-ok/>).

The F-test statistics in Table 3 fall below the threshold of 10, which is commonly used as a rule of thumb to determine whether an instrumental variable is (in the first stage) strong.

We thank Axel Dreher for bringing Lang’s (2015) approach to our attention.

Dreher and Langlotz (2015) also use this strategy to devise an excludable instrument for foreign aid disbursements.

We thank Valentin Lang for generously sharing his IMF liquidity measures.

The full set of statistical results using the alternative instrument for IMF program participation is reported in appendix I in the supporting information.

Our framing of the question in this way was inspired by the empirical design in Estevadeoral and Taylor (2013), who use a difference estimator to detect the impact of trade liberalization on economic growth.

In Giavazzi and Tabellini’s (2005) definition, the treatment group is composed of countries whose Polity2 scores went from below to above zero during the sample period.

Mumssen et al. (2013) define longer-term participants as the countries that spent at least five years out of a decade under IMF arrangements. We tried slightly less (three consecutive years) and slight more (five straight years under IMF conditional lending arrangements) restrictive definitions to construct the treatment indicator, and we found that the results were not very sensitive to these adjustments.

IMF Archives. Central Files Box #20 File #1. Country Files Series. Argentina Subseries. Letter of Intent from Minister of Economy Bernardo Grinspun to Managing Director, June 9, 1984.

References

Aaronson, S. A., & Abouharb, M. R. (2011). Unexpected bedfellows: the GATT, the WTO, and some democratic rights. International Studies Quarterly, 55, 379–408.

Abouharb, M. R., & Cingranelli, D. (2007). Human rights and structural adjustment: The impact of the IMF and world bank. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. (2012). Economics versus Politics: Pitfalls of Policy Advice. Unpublished paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA USA.

Albertus, M., & Menaldo, V. (2012). Coercive capacity and the prospects for democratization. Comparative Politics, 19(2), 151–69.

Alzer, M., & Dadasov, R. (2013). Financial liberalization and institutional development. Economics and Politics, 25(3), 424–452.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An Empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Auvinen, J. Y. (1996). IMF intervention and political protest in the third world: a conventional wisdom refined. Third World Quarterly, 17(3), 377–400.

Bailey, M., Strezhnev, A. & Voeten, E. (2015). Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data. Journal of Conflict Resolution.

Barro, R., & Lee, J.-W. (2005). IMF programs: who is chosen, and what are the effects? Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, 1245–69.

Bas, M. A., & Stone, R. W. (2014). Adverse selection and growth under IMF programs. The Review of International Organizations, 9(1), 1–28.

Berg, A., & Pattillo, C. (1999). Are currency crises predictable? a test. IMF Staff Papers, 46(2), 107–138.

Bienen, H., & Gersovitz, M. (1985). Economic stabilization, conditionality, and political stability. International Organization, 39(4), 729–54.

Birchler, K., Limpach, S. & Michaelowa, K. (Forthcoming). Aid Modalities Matter: The Impact of Different World Bank and IMF Programs on Democratization in Developing Countries. International Studies Quarterly

Brinks, D., & Coppedge, M. (2006). Diffusion is No illusion: neighbor emulation in the third wave of democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 39(4), 463–489.

Brown, C. (2009). Democracy’s friend or Foe? the effects of recent IMF conditional lending in Latin america. International Political Science Review, 30(4), 431–57.

Cameron, D. R. (2007). Post-communist democracy: the impact of the european union. Post-Soviet Affairs, 23(3), 185–217.

Carter, D. B., & Stone, R. W. (2015). Democracy and multilateralism: the case of vote-buying in the UN general assembly. International Organization, 69(1), 1–33.

Casper, B. (2015). IMF Programs and the Risk of a Coup d’état. Journal of Conflict Resolution (OnlineFirst): 1–33.

Casper, G., & Tufis, C. (2003). Correlation versus interchangeability: the limited robustness of empirical findings on democracy using highly correlated data sets. Political Analysis, 11, 196–203.

Celasun, M., & Rodrik, D. (1989). Turkish experience with debt: macroeconomic policy and performance. In J. Sachs (Ed.), Developing country debt and the world economy (pp. 193–211). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Clemens, M., Radelet, S., Bhavnani, R., & Bazzi, S. (2012). Counting chickens when they hatch: timing and the effects of Aid on growth. The Economic Journal, 122, 590–617.

Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Nozaki, M. (2011). What Happens to Social Spending in IMF-Supported Programs? IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/15.

Conway, P. (2007). The revolving door: duration and recidivism in IMF programs. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 205–220.

Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition (Vol. 254). Yale: Yale University Press.

Databanks International. (2012). Cross-national time-series data archive, 1815–2011. Binghamton: Databanks International.

Diamond, A. P., & Sekhon, J. (2013). Genetic matching for estimating causal effects: a general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 932–45.

Dietrich, S. & Wright, J.L. (2015). Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa. Journal of Politics (forthcoming).

Dreher, A. (2006). IMF and economic growth: the effects of programs, loans, and compliance with conditionality. World Development, 34(5), 769–88.

Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2012). Do IMF and World Bank Programs Induce Government Crises? An Empirical Analysis. International Organization, 66(2), 329–58.

Dreher, A., & Jensen, N. M. (2007). Independent actor or agent? an empirical analysis of the impact of U.S. Interests on international monetary fund conditions. Journal of Law and Economics, 50, 105–24.

Dreher, A. & Langlotz, S. (2015). Aid and Growth: New Evidence Using an Excludable Instrument. Unpublished paper, Heidelberg University. Available here: http://www.axel-dreher.de/Dreher%20and%20Langlotz%20Aid%20and%20Growth.pdf

Dreher, A., Sturm, J. E., & Vreeland, J. R. (2015). Politics and IMF conditionality. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(1), 120–148.

Epstein, R. A. (2005). NATO enlargement and the spread of democracy: evidence and expectations. Security Studies, 14(1), 63–105.

Eriksen, S., & de Soysa, I. (2009). A fate worse than debt? international financial institutions and human rights. Journal of Peace Research, 46, 485–503.

Estevadeoral, A., & Taylor, A. M. (2013). Is the Washington consensus dead? growth, openness, and the great liberalization, 1970s-2000s. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(5), 1669–1690.

Fearon, J., & Laitin, D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil War. The American Political Science Review, 97(1), 75–90.

Frankel, J., & Rose, A. (1996). Currency crashes in emerging markets: an empirical treatment. Journal of International Economics, 41, 351–66.

Franklin, J. (1997). IMF conditionality, threat perception, and political repression. Comparative Political Studies, 30(5), 576–606.

Gary, A. (2013). Political Stability and IFIs’ Interventions in Developing Countries. Unpublished paper, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne, Université Paris I.

Gasiorowski, M. J. (1995). Economic crisis and political regime change: an event history analysis. The American Political Science Review, 89(4), 882–897.

Geddes, B. (1999). Authoritarian breakdown: Empirical test of a game theoretic argument. Atlanta: Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Ghosh, A., et al. (2005). The design of IMF-supported programs. Washington: IMF.

Ghosh, A., et al. (2008). Modeling aggregate use of IMF resources – analytical approaches and medium-term projections. IMF Staff Papers, 55(1), 1–49.

Giannone, D. (2010). Political and ideological aspects in the measurement of democracy: the freedom house case. Democratization, 17(1), 68–97.

Giavazzi, F., & Tabellini, G. (2005). Economic and political liberalizations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, 1297–1330.

Giuliano, P., Mishra, P., & Spilimbergo, A. (2013). Democracy and reforms: evidence from a New dataset. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(4), 179–204.

Gleditsch, K. S., & Ward, M. D. (1997). Double take: a reexamination of democracy and autocracy in modern polities. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(3), 361–383.

Gleditsch, K. S., & Ward, M. D. (2006). Diffusion and the international context of democratization. International Organization, 60(4), 911–933.

Goemans, H. (2008). Which Way Out? the manner and consequences of losing office. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53(6), 771–794.

Gupta, S., de Mello, L., & Sharan, R. (2001). Corruption and military spending. European Journal of Political Economy, 17, 749–777.

Hartzell, C. A., Hoddie, M., & Bauer, M. (2010). Economic liberalization via IMF structural adjustment: sowing the seeds of civil War? International Organization, 64(2), 339–56.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236.

Hutchison, M. M. (2003). A cure worse than the disease? currency crises and the output costs of IMF-supported stabilization programs. In M. P. Dooley & J. A. Frankel (Eds.), Managing currency crises in emerging markets (pp. 321–60). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

IMF. (1999). Military Spending, the Peace Dividend, and Fiscal Adjustment. IMF Working Paper WP/99/87 (July).

IMF. (2003). IEO evaluation report: Fiscal adjustment in IMF-supported programs. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

International Financial Institutions Advisory Committee. (2000). Report of the International Financial Institution Advisory Committee. Washington, D.C. (March).

James, H. (1996). International monetary cooperation since bretton woods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Joyce, J. P., & Noy, I. (2008). The IMF and the liberalization of capital flows. Review of International Economics, 16(3), 413–30.

Kapur, D., & Naim, M. (2005). The IMF and democratic governance. Journal of Democracy, 16(1), 89–102.

Kedar, C. (2013). The international monetary fund and Latin America: the argentine puzzle in context. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Keele, L.J. (n.d). Rbounds: An R Package For Sensitivity Analysis with Matched Data. Unpublished paper, Penn State University. Accessed here: http://www.personal.psu.edu/ljk20/rbounds%20vignette.pdf

Keohane, R. O., Macedo, S., & Moravcsik, A. (2009). Democracy enhancing multilateralism. International Organization, 63(1), 1–31.

Kersting, E., & Kilby, C. (2014). Aid and democracy redux. European Economic Review, 67, 125–143.

Kirkpatrick, C., & Onis, Z. (1991). Turkey. In P. Mosley et al. (Eds.), Aid and power: The world bank & policy-based lending (volume 2: Case studies). New York: Routledge.

Lang, V.F. (2015). The Democratic Deficit and its Consequences: The Causal Effect of IMF Programs on Inequality. Unpublished paper presented at the 2015 Political Economy of International Organizations conference. Available here: http://wp.peio.me/wp-content/uploads//PEIO9/102_80_1443642587119_Lang30092015.pdf

Limpach, S. & Michaelowa, K. (2010). The Impact of World Bank and IMF Programs on Democratization in Developing Countries. University of Zurich CIS Working Paper No. 62. Available here: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1678463

Mansfield, E., & Pevehouse, J. (2006). Democratization and international organizations. International Organization, 60(1), 137–167.

Marshall, M.G. (2010). Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV) and Conflict Regions, 1946–2008. Center for Systemic Peace. Accessed here: http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm

Midtgaard, T. M., Vadlamannati, K. C., & de Soysa, I. (2014). Does the IMF cause civil War? a comment. The Review of International Organizations, 9(1), 107–24.

Morgan, S. L., & Winship, C. (2007). Counterfactuals and causal inference: Methods and principles for social research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Morrisson, C., et al. (1994). The political conditions of adjustment in Africa 1980–90. In R. van der Hoeven & F. van der Kraaij (Eds.), Structural adjustment and beyond in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 126–48). Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Mumssen, C., et al. (2013). IMF-Supported Programs in Low Income Countries: Economic Impact over the Short and Longer Term. IMF Working Paper WP/13/273 (December).

Munck, G. L., & Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies, 35(1), 5–34.

Nooruddin, I., & Simmons, J. (2006). The politics of hard choices: IMF programs and government spending. International Organization, 60, 1001–33.

Nowzad, B. (1981). The IMF and Its Critics. Princeton Essays in International Finance No. 146 (December)

Nunn, N., & Qian, N. (2014). US food Aid and civil conflict. American Economic Review, 104(6), 1630–1666.

Oberdabernig, D. A. (2013). Revisiting the effects of IMF programs on poverty and inequality. World Development, 46, 113–42.

Papaioannou, E., & Siourounis, G. (2008). Economic and social factors driving the third wave of democratization. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36, 365–87.

Payer, C. (1974). The debt trap: The international monetary fund and the third world. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Pepinsky, T. B. (2009). Economic crises and the breakdown of authoritarian regimes: Indonesia and Malaysia in comparative perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pepinsky, T. B. (2012). Do currency crises cause capital account liberalization? International Studies Quarterly, 56, 544–559.

Pevehouse, J. C. (2002). With a little help from My friends? regional organizations and the consolidation of democracy. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 611–26.

Plümper, T., & Neumayer, E. (2010). The level of democracy during interregnum periods: recoding the polity2 score. Political Analysis, 18, 206–26.

Poast, P., & Urpelainen, J. (2015). How international organizations support democratization: preventing authoritarian reversals or promoting consolidation? World Politics, 67(1), 72–113.

Przeworski, A. (1999). Minimalist conception of democracy: A defense. In Shapiro & H.-C. Casiano (Eds.), Democracy’s values, p. 23. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (1996). What makes democracies endure? Journal of Democracy, 7, 39–55.

Remmer, K. (1986). The Politics of Economic Stabilization: IMF Programs in Latin America, 1954–1984. Comparative Politics (October): 1–24.

Rickard, S. (2012). Welfare versus subsidies: governmental spending decisions in an Era of globalization. Journal of Politics, 74(4), 1171–83.

Roberts, A., Seawright, J., & Cyr, J. (2012). Do electoral laws affect Women’s representation? Comparative Political Studies. doi:10.1177/0010414012463906.

Rosenbaum, P. R. (2010). Design of observational studies. New York: Springer.

Ross, M. (2001). Does Oil hinder democracy? World Politics, 53, 325–61.

Rubin, D. B. (2006). Matched sampling for causal effects. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schmitter, P. C., & Karl, T. L. (1991). What democracy is… is not. Journal of Democracy, 2(3), 75–88.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1950). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy (3rd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Sekhon, J. (2011). Multivariate and propensity score matching software with automated balance optimization: the matching package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(7), 1–52.

Sidell, S. (1988). The IMF and third world political stability: Is there a connection? New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Simmons, B. A., & Hopkins, D. J. (2005). The constraining power of international treaties: Theory and methods. The American Political Science Review, 99(4), 623–631.

Snider, L. W. (1990). The political performance of governments, external debt service, and domestic political violence. International Political Science Review, 11(4), 403–22.

Steiner, P. M., & Cook, D. (2013). Matching and propensity scores. In T. D. Little (Ed.), Oxford handbook of quantitative methodology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2003). Globalization and its discontents. New York: W.W. Norton.

Stroup, C. & Zissimos, B. (2013). Social Unrest in the Wake of IMF Structural Adjustment Programs. CESifo Working Paper No. 4211 (April).

Sturm, J.-E., Berger, H., & De Haan, J. (2005). Which variables explain decisions on IMF credit? an extreme bounds analysis. Economics and Politics, 17(2), 177–213.

Vreeland, J.R. (1999). The IMF: Lender of Last Resort or Scapegoat? Leitner Center Working Paper 1999–03. New Haven, Conn., Department of Political Science, Yale University.

Vreeland, J. R. (2003). The IMF and economic development. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Walton, J., & Ragin, C. (1990). Global and national sources of political protest: third world responses to the debt crisis. American Sociological Review, 55, 876–90.

Weeks, J. (2008). Autocratic audience costs: regime type and signaling resolve. International Organization, 62(1), 35–64.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments on previous versions of this paper we thank Rod Abouharb, Leonardo Baccini, Henry Bienen, Jordan Gans-Morse, Katharina Michaelowa, Sophia Jordán Wallace, and participants at the Political Economy of International Organizations conference at Villanova University. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their close reading and incisive criticism. Dong Zhang provided helpful research assistance. The aforementioned are absolved of responsibility for any remaining errors, which are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

The authors declare that they have read and understand the Ethical Rules applicable to the Review of International Organizations and that this manuscript submission complies with the aforementioned Ethical Rules.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(ZIP 1340 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, S.C., Wallace, G.P.R. Are IMF lending programs good or bad for democracy?. Rev Int Organ 12, 523–558 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9250-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9250-3