Abstract

Why are some developing countries less open to technical election assistance than to election observation? My argument about who seeks and receives technical election assistance is two-fold, taking into account the incentives of recipients and providers. On the recipient side, governments are less likely to request technical assistance when the political costs are high (autocracy) or the benefits low (strong electoral institutions). On the provider side, international organizations are less likely to provide such technical assistance when the government appears to lack political will for reform and full project implementation is unlikely. Statistical analyses of global data on technical election assistance by the United Nations covering 130 countries from 1990 to 2003 support this argument about political cost-benefit calculations in considering technical assistance. Case examples from Guyana, Indonesia, Haiti, and Venezuela illustrate some of these dynamics. My findings suggest that seemingly complementary international interventions (observation and technical support) can create different incentives for domestic and international actors. This helps explain why some countries tend to agree more often to election observation than to technical election assistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For details on technical election assistance, see Section 1. In this paper, I use the terms technical election assistance, technical assistance, and technical support interchangeably.

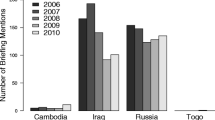

Author’s calculation based on data from Hyde and Marinov 2012 (nelda45, nelda49), Ludwig 2004b. The number of observer requests being refused (nelda49) is likely even higher than shown because these data are primarily coded from news sources; countries have no incentives and IO observers few incentives to publicly announce refusal to attend. Following prior research, I exclude 23 long-term developed democracies because they are unambiguously democratic and rarely request assistance (see footnote 74; Hyde 2011a, 74–75).

While usually not every invited observer group sends a mission, at least one observer group usually attends.

Difference in means test of provision yields p > 0.000.

Both types of election assistance have become more widespread since 2003 but the significant gap between them has persisted. See footnote 114.

See Section 1 for details.

Conditional on requests, the UN has provided technical election assistance to countries six months before election-day (on average), and in some extreme cases up to three or four years in the run-up to elections (e.g. Liberia 1997).

Examples of governments inviting observers but not technical election assistance include Azerbaijan (1993, 2003), Cameroon (1997, 2002), Swaziland (2003), Equatorial Guinea (1993, 1996, 1999, 2002), Venezuela (1993, 1998, 2000), and Zimbabwe (1990, 1995, 2002).

See Finkel et al. 2007, Savun and Tirone 2011, Scott and Steele 2011, Dietrich and Wright 2015, Bush 2015, and Savage 2015. For example, Finkel et al. use as the smallest USAID democratic governance category “elections and political processes,” which includes observation, technical election assistance, and political party support.

See Carothers 1999, 125–128; Bjornlund 2004, 60–62. Political party support is separate and can at times complement electoral assistance. Observation is provided by a host of entities (e.g. Carter Center, NDI, IRI, EU, OSCE, OAS, AU, Commonwealth, OIF) while political party support is usually provided by German Stiftungen/party foundations, or subsequent US equivalents (NDI, IRI). Lopez-Pintor 2007, 23.

Interview 6; all interviews are listed with interviewee position title, organization information, and interview date (see A). In some cases, filling equipment gaps makes the election possible at all. Recent examples include Afghanistan 2004 and Sudan 2010. Norad 2014, 30.

Kennedy and Fischer 2000, 300.

Definite numbers by all alternative providers are discussed below but difficult to establish beyond doubt. The available documentation and experts overwhelmingly point to the UN as the major provider. Interviews 3 and 5; Bjornlund 2004, 54; Pintor 2007, 23; Ludwig 1995a, 342–343; UNDP 2012, 135. Also see Section 4. In addition to the UNDP, other UN agencies providing technical election assistance – depending on country context – include the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, UN Volunteers, the Office for Project Services, and the Center for Human Rights. The Electoral Assistance Division (EAD) within the Department of Political Affairs (DPA) is the focal point for policy decisions and needs assessments.

IFES is a Washington-based NGO specializing in international election assistance; it engages in technical support to EMBs, participation-boosting measures (especially for marginalized groups), field-based research, and audits/assessments. See IFES website; interview 8.

Interviews 3, 4, 5, and 6; Diamond 2008, 123. Also see Section 4.

Promoting democratic governance constitutes one of three focus areas at the UNDP. For a historical overview of the UN’s election assistance, see Ludwig 2004b, 173–176.

The UN has several comparative advantages over other election aid organizations, including (i) it is seen as more neutral, partly because its funding generally does not depend on a single country; (ii) it can usually provide more resources in terms of project length and equipment; (iii) it tends to have more access and local knowledge due to UNDP field offices in host countries. Interviews 2 and 5; Norad 2014, 30.

See Bjornlund 2004, 62; and UN Secretary General report 2013, 3. It would be a conflict of interest for an organization to both provide technical support and observe/assess the election’s quality, effectively evaluating its own success (Interviews 5 and 8). Of the seven types of UN election assistance, four have been quite rare (supervision, verification, follow and report, organization and conduct), and support to observers (coordination of internationals, training of domestic observers) has also been far less frequent than technical election assistance. See Bjornlund 2004, 62; Ludwig 2004a, 173–176; Ludwig 1995a, 342.

UNDP 2012, 23.

Ludwig 2004a, 171. In rare cases - when the UN already has a peacekeeping mission in the country – the process begins with a mandate from the UN Security Council. Interview 5; UNDP 2012, 17. In some cases, governments consult senior UN officials in country before formally submitting a request; interview 11.

It is not possible for government agencies, an independent EMB, or opposition parties to request technical support from the UN without government confirmation. UN Secretary General report 2001, 24; interviews 2, 3, and 5. For more detailed procedures, see UN Secretary General Report 2001, annex II.

For more information, see UN EAD Ludwig (2004b).

Ludwig 1995a, 342; Ludwig 2004a, 171–173. The UN’s Election Assistance Division (EAD) is responsible for policy decisions on whether to provide election assistance. When assistance missions are not granted, the UN usually cites “insufficient lead time” and, more rarely, “the absence of enabling environment.” Ludwig 2004b, 133-161.

The requesting government can try to influence the mix of components by communicating specific gaps during the needs assessment mission, but the final decision on project components lies with the UN. Interviews 1, 3, and 5.

In such cases, states may not initiate the process with a request to the provider directly (e.g. IFES) but rather through an agreement with the funder, e.g. the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the British Department for International Development (DFID). For example, implementing partners often bid on a specific solicitation or request for proposals from funders in order to receive funding. These proposals have already undergone donor vetting and specifications, so that project conditions and components are often stipulated there, rather than the independent decision of the implementing agency. Interview 7.

Kelley 2009, 4.

In an ideal world of infinite research resources, it might be possible to systematically document country requests for observation; the variable nelda49 gives some sense of this but is likely an under-estimate, as explained in footnote 5. However, two hurdles remain. First, data collection is hampered by the seeming hesitation of some observer organizations to share these data on (un-fulfilled) invitations. Second, utilization of these data would operate on the strong assumption that the institutional memory about requests is consistent within and across organizations.

Fortna (2008, chapter 2) seeks to empirically get at the request vs. provision issue by comparing deployment of consent-based chapter 6 missions (peacekeeping) to non-consent based chapter 7 missions (peace enforcement); the latter do not technically require consent from local parties. However, that means we infer request/provision drivers from deployment differences between intervention types; this approach does not examine peace operations’ request and provision separately.

At times a third actor, the funder, can also play a role.

Note that if the government’s requests were completely random, none of the political variables should be significantly associated with requests.

Pastor 1999, 8–9.

Pastor 1999, 10.

A/62/293, 2. Also see Boutros-Ghali 1995, 5. While technically smooth processes are often a necessary condition for successful elections, they are not sufficient.

Chaubey 2011.

UNDP 2012, 35–37; Pastor 1999, 28.

Ludwig 2004b, 131.

Kandeh 2008, 606.

Lopez-Pintor 2007, 28.

UN SG report 2001, 10.

Interview 12.

If the election is rigged, manipulation takes place most often early in the electoral cycle, i.e. not on election-day but in the pre-election period, when decisions are made about the registration of voters, candidates, and parties, and campaigning begins – and other international attention is not yet focused on the country. These early decisions can restrict the playing field immensely and thus influence the outcome of the election long before the day of polling. Interview 10; Bhasin and Gandhi 2013; Norris 2014, 796.

Hyde 2011a, 158–184.

Pierson 2003.

Interviews 10 and 12.

Administrative capacity for elections and democracy levels are two distinct concepts and the empirical correlation is relatively weak (r =0.20). While they do co-vary somewhat, each level of election administrative capacity is reached by a wide range of political regimes, spanning almost the entire scale. For example, both autocracies (e.g. North Korea and Turkmenistan 2003) and advanced democracies (e.g. Costa Rica and Czech Republic 2002) have strong electoral capacity. In addition to domestic factors, the requesting decision might also be influenced by calls for reform from high profile actors outside the state. For example, when international observers have condemned the previous election, the government might be more inclined to request technical support. I control for this potential alternative explanation in the robustness section and find no empirical support.

Advanced democracies are less likely to request assistance because (i) the playing field is already fairly level and (ii) they usually have strong election institutions, so that advanced democracies would receive low benefits from capacity building.

UNDP 2002, 28.

Interview 5.

This rule is stipulated widely. See, e.g., UN Secretary General Report 2001, 24; and UN Secretary General Report 2003, 5. Exceptions to this four-month lead time are when the UN has already been engaged in the country for a long time and is merely adding a new area of support, and when the risk of civil unrest is increased. Interview 5.

Interviews 5 and 12.

Interviews 11 and 13.

Interviews 5 and 12. While short lead times can signal insincere requests for assistance in the form of political reform, they are sincere requests for financial support (interview 12). Receiving UN money for staff salaries or material is a bonus that does not require any institutional changes. In fact, financial or material support is often the only remaining option for assistance with short lead times (interview 13).

Interview 5.

Interview 10.

Interviews 5, 10, and 13.

Hyde 2011a, 74–75, footnote 29. These twenty-three democracies are Canada, US, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and European countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK.

Same-day elections are collapsed to general elections and multi-round elections are collapsed to the first round.

Interview 10. The data reflect submissions related to election assistance received by EAD from relevant UN programs.

Many country requests for assistance are broadly phrased, i.e. requesting “support” rather than support specifically for technical assistance or observers. Broad requests for UN election assistance can reasonably be seen as requests for technical election assistance because (i) the UN specializes in technical assistance, (ii) the most commonly requested type of support is technical election assistance, and (iii) the most commonly provided type of support is technical assistance (Ludwig 2004a, 176; interviews 5 and 10).

Kelley 2010, QED sr22cap, is based on U.S. State Department Human Rights Reports. I reversed the original scale to ease interpretation and collapsed no and low capacity since the lowest category was hardly populated (less than 3 % of the data). This transformation does not affect the interpretation of results.

Further in terms of data quality, the variable’s scale offers more fine-grained information than a simple 0/1 dummy; and these data are the only measure we have on election-related capacity, which underlines the difficulty of constructing such data across space and time. While this variable had missing information in about 20 % of elections in the original data source, I have filled virtually all missing values by applying the same codebook and source material. The five (out of 574) elections with remaining missing capacity information are first-time elections (for which the lagged value from the previous election thus does not exist), cases where elections had not been held in more than a decade (which renders previous elections’ capacity less relevant) and one country not mentioned in the source material due to foreign occupation. The results are substantively similar using the original (partially missing) data.

Marshall and Jaggers 2011.

The average lead time for any UN assistance is 7.5 months before the election, varying between zero and 62 months.

World Bank 2012, lagged and logged.

UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, version 4. This includes both internal and internationalized internal armed conflicts between the government and a rebel group with a minimum of 25 battle-related deaths per year.

Gilligan and Stedman 2003, 38.

Interview 11.

Kathman 2013.

World Bank 2012, lagged and logged.

Interviews 2, 3, and 5.

As explained above, we lack data on un-fulfilled requests by non-UN providers, so the request models are run on UN data “only.” Other organizations also provide technical assistance at times, but (1) often have been founded after 2003, the temporal scope of this study, and (2) even today provide technical election assistance less frequently than the UN and IFES. For example, the AU’s election assistance unit was only founded after 2006, and the first such project at the OAS was in 2008. On the NGO side, Democracy International was founded in 2003 and EISA began support to EMBs in 2002. Creative Associates’ technical elections support is limited to recent cases (South Sudan, Somaliland). Still other organizations are primarily funders (European Commission) or provide networking opportunities (International IDEA, ACE). Interviews 3, 4, 5, and 6; Diamond 2008, 123.

IFES website, accessed 4 October 2015; Kelley 2010, DIEM. According to DIEM data, the main alternative providers are NGOs (IFES, NDI, and IRI) and regional inter-governmental organizations (OSCE, Council of Europe, OAS). For more details on other providers, see footnote 94. As a result, the average rate of technical support increases from 18 to 25 %, but the significant gap to observers (67 %) remains. The result interpretation remains unaffected.

This is a conservative coding. The 40 “non” UN cases are possibly an over-estimate because some of these elections (e.g. Tajikistan 2000) are joint OSCE-UN missions which the main data source does not list.

This is estimated from model 2 in Table 2. Unless stated otherwise, all control variables are held at their mean and mode. All Tables and Figures of predicted probabilities use 95 % confidence intervals.

Interview 12.

This is predicted from model 3 in Table 2.

This is predicted from model 2 in Table 3.

The vertical line is at 2.26 because ln(8.6 + 1) =2.26. The x-axis shows the logged number of months.

For the 2000 and 1998 national elections, Venezuela asked for UN assistance within one and two months of election-day, respectively. In fact, the government of Venezuela disqualifies itself doubly: by requesting assistance with little lead time, and by repeatedly requesting observers even though the UN is very unlikely to provide these without a specific UN resolution for the election.

Author’s original data collection based on news sources and secondary research. As shown in Table 1, about 7 percent of elections in this sample are snap elections.

Ross 2012, oil and gas value per capita, lagged and logged.

Hyde and Marinov 2012, nelda12

Hyde and Marinov 2012, nelda49.

ODA, World Bank 2012.

Technical election assistance provision despite only two months or less of lead time ranges widely in recipient countries: from populations of a million in Gabon to 120 million people in Bangladesh, per capita GDP from $180 in Niger to $5,700 in Gabon, and across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe/former Soviet Union states.

Morrell 2000.

Successive missions were UMMIH (1993–1996) and UNSMIH/UNTMIH (1996–1997).

Author’s calculation based on Nelda data and original data collection on UN technical election assistance.

References

Barnett, M., Kim, H., O’Donnell, M., & Sitea, L. (2007). Peacebuilding: What is in a Name? Global Governance, 13, 35–58.

Beaulieu, E., & Hyde, S. (2009). In the shadow of democracy promotion: Strategic manipulation, international observers, and election boycotts. Comparative Political Studies, 42(3), 392–415.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: The Database of Political Institutions. World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Bhasin, T., & Gandhi, J. (2013). Timing and targeting of state repression in authoritarian elections. Electoral Studies, 32, 620–631.

Bjornlund, E. (2004). Beyond Free and Fair: Monitoring Elections and Building Democracy. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Boutros-Ghali, B. (1992). An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peacekeeping. New York: UN. Available at http://www.unrol.org/files/A_47_277.pdf.

Boutros-Ghali, B. (1995). Democracy: A Newly Recognized Imperative. Global Governance, 1(1), 3–11.

Brahimi Report / UN Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations. 2000. Available at http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/55/305 Accessed 15 January 2015.

Burnell, P. (2000). Democracy assistance: international co-operation for democratization. London.

Burnell, P. (2010). Is there a new Autocracy Promotion? FRIDE Working Paper 96.

Bush, S. (2015). The Taming of Democracy Assistance: Why Democracy Promotion Does Not Confront Dictators: Cambridge University Press.

Carothers, T. (1997). The observers observed. Journal of Democracy, 8(3), 17–31.

Carothers, T. (2006). The backlash against democracy promotion. Foreign Affairs, 85, 62.

Carothers, T., & Brechenmacher, S. (2014). Closing space: International democracy and human rights support under fire. Washington: Carnegie Endowment Report.

Carothers, T. (1999). Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Carpenter, D.P., & Krause, G.A. (2012). Reputation and public administration. Public Administration Review, 72(1), 26–32.

Chaubey, V. (2011). Cooling ethnic conflict over a heated election: Guyana 2001–2006 Working Paper, Princeton University ISS. Available at https://www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties/content/data/policy_note/PN_id167/Policy_Note_ID167.pdf Accessed 6 April 2014.

Christensen, D., & Weinstein, J. (2013). Defunding Dissent: Restrictions on Aid to NGOs. Journal of Democracy, 24(2), 77–91.

Dietrich, S., & Wright, J. (2015). Foreign aid allocation tactics and democratic change in africa. Journal of Politics, 77(1), 216–234.

Doyle, M., & Sambanis, N. (2006). Making war and building peace: United nations peace operations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Doyle, M., & Sambanis, N. (2000). International peacebuilding: a theoretical and quantitative analysis. American Political Science Review, 94(4), 779–801.

Dupuy, K., Ron, J., & Prakash, A. (2015a). Who Survived? Ethiopia’s Regulatory Crackdown on Foreign-Funded NGOs. Review of International Political Economy, 22(2), 419–456.

Dupuy, K., Ron, J., & Prakash, A. (2015b). Stop Meddling in my Country! Governments’ Restrictions on Foreign Aid to Non-Governmental Organizations. Working Paper.

Finkel, S., Linan, A.P., & Seligson, M. (2007). The effects of U.S. Foreign assistance on democracy building, 1990–2003. World Politics, 59(3), 404–440.

Fortna, P. (2008). Does peacekeeping work? Shaping belligerents’ choices after civil war. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fortna, P. (2004). Does peacekeeping keep peace? International intervention and the duration of peace after civil war. International Studies Quarterly, 48, 269–292.

Fortna, P., & Howard, L. (2008). Pitfalls and prospects in the peacekeeping literature. Annual Review of Politicial Science, 11, 283–301.

Gandhi, J., & Lust-Okar, E. (2009). Elections under authoritarianism. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 403–22.

Geddes, B. (1994). Politician’s dilemma. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gershman, C., & Allen, M. (2006). The assault on democracy assistance. Journal of Democracy, 17(2), 36–51.

Gilligan, M., & Stedman, S.J. (2003). Where do the Peacekeepers Go? International Studies Review, 5(4), 37–54.

Hyde, S. (2007). The observer effect in international politics. Evidence from a natural experiment. World Politics, 60, 37–63.

Hyde, S. (2011a). The Pseudo-Democrat’s Dilemma. Why election monitoring became an international norm: Cornell University Press.

Hyde, S. (2011b). Catch us if you can: Election monitoring and international norm diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 356–369.

Hyde, S., & Marinov, N. (2012). Which Elections can be lost? Political Analysis, 20(2), 191–210.

Hyde, S., & O’Mahony, A. (2010). International scrutiny and Pre-Electoral fiscal manipulation in developing countries. Journal of Politics, 72(3), 1–14.

Ichino, N., & Schündeln, M. (2012). Deterring or Displacing Electoral Irregularities? Spillover Effects of Observers in a Randomized Field Experiment in Ghana. Journal of Politics, 74(1), 292–307.

International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). (2012). Celebrating 25 years. DC: IFES.

Kandeh, J. (2008). Rogue incumbents, donor assistance and Sierra Leone’s second post-conflict elections of 2007. Journal of Modern African Studies, 46(4), 603–635.

Kathman, J. (2013). United Nations Peacekeeping Personnel Commitments, 1990-2011. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 30(5), 532–549.

Kelley, J. (2012). Monitoring Democracy: When International Election Observation Works, and Why It Often Fails: Princeton University Press.

Kelley, J. (2010). Data on international election monitoring: Three Global Datasets on Election Quality, Election Events and International Election Observation.

Kelley, J. (2009). The more the merrier? the effects of having multiple international election monitoring organizations. Perspectives on Politics, 7(1), 59–64.

Kelley, J. (2008). Assessing the complex evolution of norms: The rise of international election monitoring. International Organization, 62, 221–55.

Kennedy, R., & Fischer, J. (2000). Technical assistance in elections. In R. Rose (Ed.), International encyclopedia of elections (pp. 300–305). Washington: CQ Press.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–61.

Lehoucq, F., & Molina, I. (2002). Stuffing the ballot box: Fraud, election reform and democratization in Costa Rica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lopez-Pintor, R. (2007). What is entailed in Technical Electoral Assistance? In R. W. Soudriette, & J. G. Pilon (Eds.), Every Vote Counts: The Role of Elections in Building Democracy. Lanham: University Press of America.

Ludwig, R. (1995a). Processes of democratization: The new role of the United Nations in electoral assistance. The Ecumenical Review, 47(3), 339–343.

Ludwig, R. (2004a). The UN’s Electoral Assistance. Challenges, Accomplishments, and Prospects. In The UN role in promoting democracy: Between ideals and reality (pp. 169–187). New York: UN University Press.

Ludwig, R. (2004b). Free and fair elections: Letting the people decide. In J. Krasno (Ed.) The United Nations: Confronting the challenges of a global society (pp. 115–162). London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Maor, M., & Sulitzeanu-Kenan, R. (2015). Responsive change: Agency output response to reputational threats. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory.

Marshall, M.G., & Jaggers, K. (2011). Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2010 dataset user’s manual. College Park: University of Maryland. Available at http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4manualv2010.pdf Accessed 18 September 2012.

McFaul, M. (2004). Democracy promotion as a world value. Washington Quarterly, 28(1), 147–163.

Morrell, J.R. (2000). Snatching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory. Center for International Policy.

Norris, P., Franka, R., & i Coma, F.M. (2014). Measuring electoral integrity around the world: a new dataset. PS: Political Science and Politics, 47(4), 789–798.

Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad). (2014). Results report: Human rights and democracy. Oslo: Norad.

Pastor, R.A. (1999). The role of electoral administration in democratic transitions: Implications for policy and research. Democratization, 6(4), 1–27.

Pierson, P. (2003) In J. Mahoney, & D. Rueschemeyer (Eds.), Big, Slow-Moving, and... Invisible: Macrosocial Processes in the Study of Comparative Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ponzio, R. (2004). UNDP experience in long-term democracy assistance. In Newman, E., & Rich, R. (Eds.) The UN role in promoting democracy: between ideals and reality (pp. 208–229). New York: UN University Press.

Risse, T., & Babayan, N. (2015). Democracy promotion and the challenges of illiberal regional powers: introduction to the special issue. Democratization, 22(3), 381–399.

Ross, M. (2012). The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations: Princeton University Press.

Santa-Cruz, A. (2005). Constitutional structures, sovereignty, and the emergence of norms: The case of international election monitoring. International Organization, 59(3), 663–93.

Savage, J.D. (2015). Military size and the effectiveness of democracy assistance. Journal of Conflict Resolution.

Savun, B., & Tirone, D. (2011). Foreign Aid, Democratization, and Civil Conflict: How Does Democracy Aid Affect Civil Conflict? American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 233–246.

Scott, J., & Steele, C. (2011). Sponsoring democracy: The United States and democracy aid to the developing world, 1988–2001. International Studies Quarterly, 55, 47–69.

Simpser, A. (2013). Why governments and parties manipulate elections: Theory, practice and implications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Simpser, A., & Donno, D. (2012). Can International Election Monitoring Harm Governance? Journal of Politics, 74(2), 501–513.

Stojek, S.M., & Tir, J. (2014). The supply side of United Nations peacekeeping operations: Trade ties and United Nations-led deployments to civil war states. European Journal of International Relations, 1–25.

United Nations. (2005). Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation and Code of Conduct for International Election Observers. New York: UNDP.

United Nations (2008). United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines.

United Nations Department of Political Affairs (UNDPA). (2002). Member States’ Requests for Electoral Assistance to the United Nations System. New York: UNDPA. Used to be available at http://www.un.org/Depts/dpa/ead/assistance_by_country/ea_assistance.htm Accessed 22 July 2008.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2002). UNDP and electoral assistance: Ten years of experience. New York: UN.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2010). Assessment of development results: Guyana. New York: UN.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2012). Evaluation of UNDP contribution to strengthening electoral systems and processes. New York: UN.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2013). The role of the UNDP in supporting democratic elections in Africa. New York: UN.

United Nations Election Assistance Division (2012). United Nations Electoral Needs Assessments. New York: UN. FP/02/2012.

UN Secretary General Report (2001). Enhancing the effectiveness of the principle of periodic and genuine elections. A/56/344.

UN Secretary General Report (2003). Strengthening the Role of the United Nations in enhancing the effectiveness of the principle of periodic and genuine elections and the promotion of democratization. A/58/212.

UN Secretary General Report (2013). Strengthening the Role of the United Nations in enhancing the effectiveness of the principle of periodic and genuine elections and the promotion of democratization. A/68/301.

UN Targeted Sanctions Project (n.d). Evaluating the Impacts and Effectiveness of Targeted Sanctions: Somalia. Available at http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/internationalgovernance/shared/PSIG_images/Sanctions/Templates/Somalia%20Template.doc Accessed 15 November 2015.

USAID. (2014). Review of USAID/Afghanistan’s Electoral Assistance Program. Report No F-306-14-001-S. DC: USAID.

USAID. (2000). Managing assistance in support of political and electoral processes. DC: USAID.

World Bank (2012). Development Indicators. Available at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

Acknowledgments

I thank Gabrielle Bardall, Sarah Bush, Amanda Clayton, Jess Clayton, Susan Hyde, Mert Kartal, Jon Pevehouse, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors. Rebecca Saylor provided excellent research assistance. Part of this project was completed during a postdoctoral research fellowship at the KFG “The Transformative Power of Europe” at the Free University Berlin, which is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews

I conducted semi-structured interviews with experts at a range of organizations providing technical election assistance, including the United Nations and two NGOs. At the United Nations, interviewees were based at the Development Programme (UNDP) and the Electoral Assistance Division (UNEAD) which is part of the Department of Political Aairs (UNDPA). Among the NGOs, interviewees were based at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) and Creative Associates. Experts were either at the associate or senior level, including Senior Election Advisors, Electoral Policy Specialists, and Electoral Policy Analysts.

- Interview 1::

-

United Nations, 19 June 2015

- Interview 2::

-

United Nations, 26 June 2015

- Interview 3::

-

United Nations, 26 June 2015

- Interview 4::

-

NGO, 3 July 2015

- Interview 5::

-

United Nations, 9 July 2015

- Interview 6::

-

NGO, 7 August 2015

- Interview 7::

-

NGO, 25 September 2015

- Interview 8::

-

NGO, 21 October 2015

- Interview 10::

-

United Nations, 3 March 2016

- Interview 11::

-

United Nations, 4 March 2016

- Interview 12::

-

United Nations, 4 March 2016

- Interview 13::

-

United Nations, 4 March 2016

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borzyskowski, I.v. Resisting democracy assistance: Who seeks and receives technical election assistance?. Rev Int Organ 11, 247–282 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9249-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9249-9

Keywords

- International organizations

- United Nations

- Developing countries

- Elections

- Democracy promotion

- Technical election assistance