Abstract

Purpose

This study described physical and psychosocial limitations associated with adult brachial plexus injuries (BPI) and patients’ expectations of BPI surgery.

Methods

During in-person interviews, preoperative patients were asked about expectations of surgery and preoperative and postoperative patients were asked about limitations due to BPI. Postoperative patients also rated improvement in condition after surgery. Data were analyzed with qualitative and quantitative techniques.

Results

Ten preoperative and 13 postoperative patients were interviewed; mean age was 37 years, 19 were men, all were employed/students, and most injuries were due to trauma. Preoperative patients cited several main expectations, including pain-related issues, and improvement in arm movement, self-care, family interactions, and global life function. Work-related expectations were tailored to employment type. Preoperative and postoperative patients reported that pain, altered sensation, difficulty managing self-care, becoming physically and financially dependent, and disability in work/school were major issues. All patients reported making major compensations, particularly using the uninjured arm. Most reported multiple mental health effects, were distressed with long recovery times, were self-conscious about appearance, and avoided public situations. Additional stresses were finding and paying for BPI surgery. Some reported BPI impacted overall physical health, life priorities, and decision-making processes. Four postoperative patients reported hardly any improvement, four reported some/a good deal, and five reported a great deal of improvement.

Conclusions

BPI is a life-altering event affecting physical function, mental well-being, financial situation, relationships, self-image, and plans for the future. This study contributes to clinical practice by highlighting topics to address to provide comprehensive BPI patient-centered care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adult brachial plexus injuries (BPI) are devastating events due to trauma or as a result of treatments for other medical conditions [2, 4, 6, 13]. Improvements in microsurgical techniques have made nerve repair and reconstruction possible for selected BPI patients [4]. These treatments and their rehabilitation regimens are complex and costly [9, 14].

The goal of BPI surgery is to improve quality of life and restore as much function as possible [2]. However, success of surgery currently is often measured by physicians according to physical examination and physician-derived scales that focus on motor function [2, 5, 12, 13]. While these measures provide valuable information, they may miss aspects of the experience that are most important to patients, such as appearance and emotional well-being [2, 7, 16]. In addition, although there are valid patient-reported scales for disorders of the upper extremity, they may not capture the complex and severe physical and psychosocial impact of BPI [2, 7, 9, 11, 17, 18]. These issues are particularly relevant for patients shortly after surgery because psychological well-being and its impact on rehabilitation during this time period are critical to what ultimately will be the outcome of surgery.

This study is the first phase of a trajectory of work to develop and validate a BPI-specific patient-reported scale that addresses the preoperative and postoperative physical and psychological impact of BPI, as well as change in condition over time. The current report provided details from this first phase which was a qualitative study involving in-depth interviews with preopertive and postoperative patients to ascertain their expectations of surgery and their experiences with BPI, particularly the impact of BPI on quality of life and functional status.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the IRB at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and all patients provided written informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Preoperative Patients

Preoperative patients were included if they were 18 years old or older and scheduled to undergo reconstructive surgery within the next several days for recently sustained partial or complete BPI. Consecutive patients were enrolled at the time of a routine preoperative visit with their surgeons or when they returned to the hospital for preoperative testing. Patients were interviewed in person by a single investigator experienced in qualitative research and were asked these open-ended questions about their expectations: “What do you expect as a result of your surgery? After you have recuperated from your surgery, what do you expect will be different?” Patients were encouraged to cite as many expectations as they wished and their verbatim responses were recorded in field notes. We emphasized that we were asking about what they expected, not what they hoped for. Enrollment continued until data saturation, defined as when no new expectations were volunteered. Patients also were asked about how the injury impacted their lives with these open-ended questions: “What bothers you the most about your arm? What valued activities can’t you do as well now because of your arm? What accommodations have you had to make because of your arm?”

Postoperative Patients

Postoperative patients were included if they had undergone reconstructive surgery for a partial or complete BPI within the prior 9–24 months. The short-term postoperative period was selected because rehabilitation is still in progress, many patients are not yet resigned to permanent disability, and patients can still attribute limitations and difficulties in their lives exclusively to BPI. Consecutive patients were enrolled at the time of routine follow-up visits with their surgeons and were interviewed in person by the same investigator with these open-ended questions: “What would you say is the outcome or result of your surgery? What is better now? What is still the same? What is worse? What bothers you the most now about your arm?” Patients were encouraged to report any activities or emotions they wished; enrollment continued until data saturation and their responses were recorded verbatim in field notes.

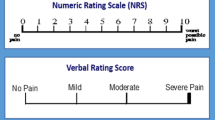

All patients were asked to rate their overall current condition using the following adaptation of a valid single item seven-point measure of well-being: “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your arm condition just the way it has been in the last 24 h, how would you feel?” with response options of “delighted,” “pleased,” “mostly satisfied,” “mixed—about equally satisfied and dissatisfied,” “mostly dissatisfied,” “unhappy,” or “terrible” [1]. Because this question is framed by a specific time period, it is more tangible than a general abstract question about satisfaction. Demographic information was obtained from patients and information about level of BPI (C5-6, C5-6-7, C7-T1, complete, upper trunk) was obtained from medical records.

Data Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described with means and frequencies. All open-ended responses were reviewed with standard qualitative techniques using grounded theory, a methodology in which verbatim responses are sequentially aggregated into larger themes through an iterative process. Specifically, during the initial open coding phase all verbatim responses were analyzed line by line to identify unique concepts. Concepts were then aggregated into categories based on similarities to each or based on specific phenomena [3, 21]. The entire process was driven by patients’ perspectives and not by investigators’ a priori hypotheses. Codes were then assigned to categories and the verbatim responses were then reviewed again to determine the prevalence of categories. Although the formal analysis took place after all data had been acquired, as the interviews progressed the investigators noted when no new perspectives were being volunteered, i.e., data saturation, at which point no new patients were enrolled. The qualitative analysis was corroborated by two investigators (corroboration), one was a methodologist with expertise in qualitative research and the other was an orthopedic surgeon with expertise in upper extremity surgery. Each investigator conducted the qualitative analysis independently to discern concepts and categories and then through consensus arrived at the final set of categories.

Results

Ten preoperative and 13 postoperative patients were enrolled from April 1, 2013, to March 18, 2014; no patients refused to participate. The mean age was 37 ± 14 years (range 19–63), 19 were men, and all were working or were full-time students at the time of the injury.

Among preoperative patients, four had complete and six had partial plexopathy, and the mode of injury was from a motorcycle accident (six), recreational vehicle accident (three), or as a consequence of cervical spine surgery (one). The mean time from injury to enrollment was 7 ± 3 months and from enrollment to subsequent surgery was12 ± 13 days. In response to the question about how they would feel if they had their current condition for the rest of their life, two reported mixed (equally satisfied and dissatisfied), one mostly dissatisfied, three unhappy, and four terrible.

Among postoperative patients, six had complete and seven had partial plexopathy, and the mode of injury was from a motorcycle accident (five), motor vehicle accident (six), oncologic radiation therapy (one), or prolonged malposition during critical care for a bowel perforation (one). The mean time from injury to enrollment was 33 ± 37 months, and the mean time from surgery to enrollment was 14 ± 4 months (range 10–22 months). In response to the question about how they would feel if they had their current condition for the rest of their life, three reported pleased, two mostly satisfied, three mixed, two mostly dissatisfied, one unhappy, and two terrible.

Preoperative Patients’ Expectations

Preoperative patients cited pain-related issues as major expectations, including decrease in pain severity and better response to pain medications (Table 1). Improvement in function was another major expectation with most patients citing major activities related to gross movement of the arm, self-care, family interactions and, to a lesser extent, discretionary activities, such as sports. All patients had expectations related to work which were tailored to the type of employment, for example, using a telephone and computer for office workers (i.e., lawyer, financial analyst) and regaining range of motion and strength for manual laborers (i.e., mechanics). Some patients spoke in general terms with expectations of restored global function and noted the need to shift their focus from enjoyable activities to accomplishing basic activities of daily living.

Patients reported they learned about BPI surgery and derived their expectations mostly from their own internet research, including hospital websites and blogs with other patients. Some patients were concerned about having overly ambitious expectations and wanted to avoid disappointment (“I know things could get worse.”). In some instances, patients were cautious (“After speaking with my surgeon I now know I will not be back to normal.”).

Preoperative Patients’ Symptoms, Physical Limitations, and Mental Health Effects

Preoperative patients reported both continuous and intermittent severe pain that varied in quality (Table 2). They also cited limitations in managing essential activities, such as eating and self-care, and becoming dependent on others for these activities. All patients cited devastating effects on work with the inability to continue current employment or attend school. Many had become financially dependent on others because of work disability. Some patients reported they were unable to participate in sports and mourned the loss of their preinjury physique and fitness. All patients reported they had made major compensations, mostly to rely on the uninjured arm. Patients also reported they were self-conscious in front of others about their disability and appearance, and purposefully avoided social and professional public situations.

All patients cited effects of BPI on their mental health with a spectrum of depressive, anxiety, and anger symptoms (Table 3); some patients had considered suicide. Patients reported they received emotional support from their social network (“We have a hot line at work.”; “My wife is key to the situation.”) and some had professional counseling and treatment; however, success of treatment varied among patients. The injury also precipitated loss of relationships (“I separated from my wife right after this happened. She is not the type to get through things like this.”). A few patients spoke openly about their determination to think positively and move forward with their lives (“I stay upbeat. I can’t go back and change things. I have to deal with it.”; “I am a very positive person. Nothing bothers me. I am church going, I know God will take care of me.”).

Some patients viewed their injury as a way to teach others (“I want my son to see me struggle and to see my pain. This way he will stay out of trouble. I want him to learn there are consequences. I don’t want him to do anything stupid…It wasn’t my fault…But I don’t want him to take unnecessary chances.”). Some patients commented about remembering the accident (“I don’t know what happened and I don’t want to know.”; “I wasn’t lucky like some people—I wasn’t knocked out, I remember the whole thing; I relive the whole thing.”), and others commented that their accident was unforeseeable (“I don’t know what happened. I just went to get gas. It is ironic.”).

An additional source of stress was finding and paying for surgery (“My doctors told me there was nothing else that could be done; so I took matters into my own hands.”; “I found out about this surgery myself. My regular doctors didn’t know what I had, they didn’t know about this surgery…that’s why it took so long to get here, that and all the trouble with insurance.”).

Postoperative Patients’ Symptoms, Physical Limitations, and Mental Health Effects

Most postoperative patients still had pain, but generally, it was improved (Table 4). Sensation was a new topic and most commented that they had abnormal feeling in their arm and hand. Return of movement was reported by most patients; however, function with respect to fulfilling essential activities was still notably impaired. Maintaining work and school continued to be major challenges and some patients relied on others for help (“I do studies on-line now. I need extended time on tests or my mother has to do it. I can’t type yet, I can’t use a mouse.”). Loss of ability to compete in desired sports also was noted and some patients had switched to other sports. Patients also continued to compensate with the uninjured arm for many daily activities. They also compensated by using special devices, like new cooking utensils, sports equipment, and workplace tools.

Patients reported multiple emotions that persisted after surgery (Table 5). These included depressive symptoms, frustration, anger, guilt, anxiety, and remorse at losing enjoyable discretionary activities. For some patients, the emotional reaction was debilitating and required psychiatric care. There also were strong feelings about the time required to heal with most patients commenting they were distressed with the recovery time even though many reported they had been advised about this (“The recuperation is long, but not longer than expected because my surgeon told me; everything is on schedule.”). A few patients were so frustrated with the time to heal that they claimed amputation might be better; however, none were actively seeking this drastic intervention (“It is frustrating. I would rather have it gone. It is in my way. I always have to worry about it. I don’t want to do this for the rest of my life. If it is not going to get any better, I would rather they take it off.”). Some patients noted the irony that they recuperated from life-threatening injuries also incurred during the accident, but it is the non life-threatening BPI that will cause them life-long disability. Most patients coped with their emotions by keeping busy, by drawing on their own inner strength (“I had the mindset that disability would not overcome me”), and by relying on their social network. Some patients, however, were ambivalent about depending on others for help (“In the last few months I have become a little bothered. I go to the store and people offer to help me, to pack my groceries. I appreciate their offer but I don’t want to rely on others for help. My daughter’s boyfriend is very handy, I ask him for certain things; he is a God send. But at the same time I don’t want to ask for help.”). For the most part, patients were still disheartened by the appearance of their arm even though there were improvements. Appearance continued to limit their willingness to participate in social activities.

Finally, some postoperative patients took a global view of their situation and commented that the injury had ramifications for their long-term overall physical health, life priorities, and decision-making processes. Many also stated that because they were still early in the recuperation process, they anticipated additional improvement in their condition.

Discussion

Patients reported devastating effects of BPI on their physical and mental well-being. In most cases, the impact was life altering, affecting basic activities of daily living and self-care, and rendering patients disabled for complex integrated functions, such as sustained employment. In addition, expectations of surgery tended to be global in nature, primarily focusing on pain relief and restored arm movement.

The profile of limitations and expectations of BPI patients reflects both the severity and abruptness of the affliction. This is in stark contrast to the profile of patients undergoing other types of upper extremity surgery, such as shoulder surgery, which tends to reflect nuanced activities that are being gradually lost due to chronic conditions [15]. As such, broad assessments of pain severity and ability to perform essential activities may be the appropriate indicators for change in preoperative and immediate postoperative BPI patients.

We found variations in symptoms and disabilities for both preoperative and postoperative groups. This may be attributed to several factors. For preoperative patients, this may be due to variation in the time between the injury and surgery. Some patients who had lived with BPI longer may have come to acknowledge their new reality and already had some success in making accommodations. It may be these patients viewed surgery as a way to optimize their situation while those with very recent injuries viewed surgery as a way to be restored to their preinjury state. Variations in symptoms and disabilities for postoperative patients also may have been due to variation in the time between injury and surgery as well as to variation in the type of surgery performed. In addition to being tailored to the degree and location of the injury, in some cases, surgery was planned to be a staged process and was still in progress. We preferentially included only short-term postoperative patients, and they were aware that additional improvement was likely. This was reflected by those patients who reported they were better because of surgery, but they would not be pleased if they had to spend the rest of their lives in their current condition.

Only a few other studies attempted to measures patient-reported effects of BPI. In one study, researchers queried 32 patients a mean of 7 years postoperatively using a physician-derived survey and found adverse impacts on leisure activities, health, financial situation, and employment [4]. Another study of 25 patients a mean of 3 years postoperatively used existing patient-reported scales to measure effects of BPI, and found marked disability in emotional well-being and physical function [10]. Our study confirms these effects and, by using qualitative techniques, provides new information about how patients begin to compensate for BPI. In another study, other investigators also used qualitative techniques to assess BPI by interviewing 12 patients at least 1 year postoperatively or post injury for nonsurgical patients [7]. This study reported patients had emotional effects including anger, frustration, depression, mourning, less energy, and decreased self-efficacy and self-esteem. Patients also had major changes in education, employment, and outlook on life, felt social discomfort and unattractiveness, and regretted their increased reliance on others for daily activities and finances. Satisfaction with outcome of surgery varied and was associated with pain, dysfunction, and work disability [8]. The findings of our study support the results of this study and provide additional details about the devastating effects of BPI on all aspects of life. Several other qualitative studies have been conducted focusing on neonatal brachial plexus palsy; these studies reported profound effects on child and adolescent emotional, social, and physical function as well as body image, finances, and family dynamics [19, 20].

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a subspecialty BPI center and may not be representative of patients treated in other settings. Second, patients were a heterogeneous group with respect to the degree of plexus injury. Third, patients were interviewed at the time of a clinical visit and their responses may have been influenced by the most recent information they received from surgeons and staff.

This qualitative study demonstrated that BPI patients have diverse expectations and limitations that center mainly on pain and essential activities of daily living. This study contributes to the management of BPI patients by highlighting topics to address to provide comprehensive patient-centered care. This study also provides a foundation to develop a BPI-specific patient-reported scale.

References

Andrews FM, Withey SB. Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum Press; 1976.

Bengtson KA, Spinner RJ, Bishop AT, Kaufman KR, Coleman-Wood K, Kircher MF, et al. Measuring outcomes in adult brachial plexus reconstruction. Hand Clin. 2008;24(4):401–15.

Berkowitz M, Inui TS. Making use of qualitative research techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):195–9.

Choi PD, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE, Kline DG. Quality of life and functional outcome following brachial plexus injury. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22(4):605–12.

Dy CJ, Garg R, Lee SK, Tow P, Mancuso CA, Wolfe SW. A systematic review of outcomes reporting for brachial plexus reconstruction. J Hand Surg. 2015;40(2):308–13.

Eggers IM, Mennen U. The evaluation of function of the flail upper limb classification system: its application to unilateral brachial plexus injuries. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26(1):68–76.

Franzblau L, Chung KC. Psychosocial outcomes and coping after complete avulsion traumatic brachial plexus injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(2):135–43.

Franzblau LE, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. Patient satisfaction and self-reported outcomes after complete brachial plexus avulsion injury. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2014;39(5):948–55.

Hill BE, Williams G, Bialocerkowski AE. Clinimetric evaluation of questionnaires used to assess activity after traumatic brachial plexus injury in adults: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(12):2082–9.

Holdenried M, Schenck TL, Akpaloo J, Muller-Felber W, Holzbach T, Giunta RE. Quality of life after brachial plexus lesions in adults. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2013;45(4):229–34.

Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602–8.

James MA. Use of the medical research council muscle strength grading system in the upper extremity. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2007;32(2):154–6.

Kretschmer T, Ihle S, Antoniadis G, Seidel JA, Heinen C, Borm W, et al. Patient satisfaction and disability after brachial plexus surgery. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(4):A189–96.

Lad SP, Nathan JK, Schubert RD, Boakye M. Trends in median, ulnar, radial, and brachioplexus nerve injuries in the United States. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(5):953–60.

Mancuso CA, Altchek DW, Craig EV, Jones EC, Robbins L, Warren RF, et al. Patients’ expectations of shoulder surgery. J Should Elb Surg. 2002;11(6):541–9.

Novak CB, Anastakis DJ, Beaton DE, Mackinnon SE, Katz J. Validity of the Patient Specific Functional scale in patients following upper extremity nerve injury. HAND. 2013;8(2):132–8.

Novak CB, Anastakis DJ, Beaton DE, Mackinnon SE, Katz J. Biomedical and psychosocial factors associated with disability after peripheral nerve injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(10):929–36.

Penta M, Thonnard JL, Tesio L. ABILHAND: a Rasch-built measure of manual ability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(9):1038–42.

Sarac C, Bastiaansen E, van der Holst M, Malessy MJA, Nelissen RGHH, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Concepts of functioning and health important to children with an obstetric brachial plexus injury: a qualitative study using focus groups. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(12):1136–42.

Squitieri L, Larson BP, Chang KW, Yang LJ, Chung KC. Understanding quality of life and patient expectations among adolescents with neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a qualitative and quantitative pilot study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2013;38(12):2387–97.

Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an internal institutional grant from Richard Menschel for personnel funding and research registry support.

Conflicts of Interest

Carol A Mancuso declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Steve K Lee declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Christopher J Dy declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Zoe A Landers declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Zina Model declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Scott W Wolfe declares that he has no conflict of interest.

The study was supported by a grant form Richard Menschel for personnel funding and research registry support.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Hospital for Special Surgery. This study included only human; there were no animals.

Statement of Informed Consent

All patients provided written informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Mancuso, C.A., Lee, S.K., Dy, C.J. et al. Expectations and limitations due to brachial plexus injury: a qualitative study. HAND 10, 741–749 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-015-9761-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-015-9761-z