Abstract

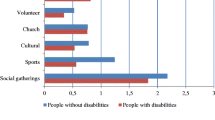

This study analyses the effect of participating in leisure activities on the levels of life satisfaction reported by people with and without disabilities. Particular attention is paid to exploring how different types of leisure activities (e.g. social gatherings, cultural events, active sports, volunteer work, etc.) affect individuals’ life satisfaction and which of them contribute most to improving it. Using longitudinal data at an individual level from the German Socio-Economic Panel, we estimate a “Probit Adapted OLS (POLS)” model which allows us to identity the determinants of life satisfaction by disability status and to control for the unobserved heterogeneity and thus determine cause and effect between the key variables. Although participation in leisure activities increases the life satisfaction scores reported by people with disabilities (except for the participation in public initiatives), this effect is quite different by leisure activity. The participation in leisure activities such as holidays, going out, or attending cultural events and church has a significant positive effect on the life satisfaction of people with disabilities. Event organizers, destination managers, business owners, professionals, governments, and the leisure industry in general must promote and facilitate full access and participation of people with disabilities in all leisure activities, especially in those that contribute more intensely to increasing their life satisfaction scores. The elimination of all disabling barriers, the understanding of their differential needs and the existence of inclusive leisure environments are key elements for improving the life satisfaction of people with disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For some leisure activities (e.g. participation in public initiatives, doing volunteer work, taking part in active sports, going to the cinema and cultural events) we can find more information for other years included in the GSOEP. In addition, the wording of the questions used in this study on free time and possible answers has changed slightly over the years. Additional information on methodology aspects of the GSOEP (e.g. target populations, sampling, survey design, questionnaires, generated variables, weights, etc.) is available at: http://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222847.en/desktop _companion_overview.html.

In line with Becchetti et al. (2012), it is likely that the distance from “at least once a month” and “daily/weekly” corresponds to a more than proportional increase in life satisfaction than the distance between “seldom” and “at least once a month”. If this is the case, our leisure measure flattens the high intensity response and may be conceived as a sort of log transform of the true unobserved variable. A similar strategy is followed by Lancee and Radl (2012). In any case, we have re-estimated all our life satisfaction equations by introducing different options. First, we have used different coding schemes for the distances between the possible answers and the results were extremely similar to those shown in Table 1. Second and following Winkelmann (2009), we have also created a dummy variable for each leisure activity that equals 1 if the individual is engaged in that activity with a “daily/weekly” frequency, and zero otherwise. Once again, the results obtained did not alter the main conclusions of our study.

For example, see Sirgy (2012) for a full review of the concept of life satisfaction (chapter 1).

The reason for using this measure is that if we look at the GSOEP questionnaire, we find that the work limitation question has been changed over time and it was not asked in all its waves (from 1988 to 1991 and in 1993 and 1994, or at all from 2002 onwards).

This test is based on the inclusion of three additional variables in our model: (1) the number of waves in which the ith individual participates in the panel; (2) a binary variable taking the value 1 if and only if the ith individual is observed over the entire sample and 0 otherwise; and (3) a binary variable indicating whether the individual was observed in the previous period.

References

Baldwin, K., & Tinsley, H. (1988). An investigation of the validity of Tinsley and Tinsley’s (1986). Theory of leisure experience. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(3), 263–267.

Bastug, G., & Duman, S. (2010). Examining life satisfaction level depending on physical activity in Turkish and German societies. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 4892–4895.

Becchetti, L., Ricca, E., & Pelloni, A. (2012). The relationship between social leisure and life satisfaction: causality and policy implications. Social Indicators Research, 108, 453–490.

Bedini, L. (2000). Just sit down so we can talk: perceived stigma and the pursuit of community recreation for people with disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal., 34, 55–68.

Benum, K., Anstorp, T., Dalgard, O., & Sorensen, T. (1987). Social network stimulation: Health promotion in a high risk group of middle-aged women. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia Supplement, 76(337), 33–41.

Brajsa-Zganec, A., Merkas, M., & Sverko, I. (2011). Quality of life and leisure activities: How do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 102, 81–91.

Bruni, L., & Stanca, L. (2006). Income aspirations, television and happiness: Evidence from the world values survey. Kyklos: internationale Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaften, 59(2), 209–226.

Buhalis, D., & Darcy, S. (2011). Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues. Bristol: Channel View.

Burkhauser, R., & Schroeder, M. (2007). A method for comparing the economic outcomes of the working-age population with disabilities in Germany and the United States. Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 127(2), 227–258.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381.

Clark, A., Diener, E., Georgelli, Y., & Lucas, R. (2008). “Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis.” Economic Journal, 118(259), F222–F243.

Coleman, J. (1993). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Collins.

Dattilo, L. (1994). Inclusive leisure services: Responding to the rights of people with disabilities. State College: Venture Publishing.

Delle Fave, A., & Bassi, M. (2003). Italian adolescents and leisure: The role of engagement and optimal experience. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 99, 79–94.

Devine, M. A. (1997). Inclusive leisure services and research: Consideration of the use of social construction theory. Journal of Leisurability, 24(2), 3–11.

Devine, M. A., & Dattilo, J. (2001). The relationship between social acceptance and leisure lifest^des of people witli disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 34(4), 306–322.

Devine, M., & Lashua, B. (2002). Constructing social acceptance in inclusive leisure contexts: The role of individuals with disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 36, 65–83.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Dolnicar, S., Yanamandram, V., & Cliff, K. (2012). The contribution of vacations to quality of life. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 59–83.

Dowall, J., Bolter, C., Flett, R., & Kammann, R. (1988). Psychological well-being and its relationship to fitness and activity levels. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 14(1), 39–45.

Frey, B. S., Benesch, C., & Strutzer, A. (2005). Does watching TV make us happy? Zurich: University of Zurich, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics.

Frisch, M. (1998). Quality of life therapy and assessment in health care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 19–40.

Helliwell, J., & Putman, R. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Iwasaki, Y., & Smale, B. (1998). Longitudinal analyses of the relationship among life transitions, chronic health problems, leisure, and psychological well-being. Leisure Sciences, 20, 25–52.

Koohsar, A., & Bonab, B. (2011). Relation between quality of attachment and life satisfaction in high school administrators. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 954–958.

Lancee, B., & Radl, J. (2012). Social connectedness and the transition from work to retirement. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(4), 481–490.

Laukka, P. (2007). Uses of music and psychological well-being among the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 215–241.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. (2005). Multiple determinants of life quality: The roles of Internet activities use of new media, social support, and leisure activities. Telematics and Informatics, 22, 161–180.

Lloyd, K., & Auld, C. (2002). The role of leisure in determining quality of life: Issues of content and measurement. Social Indicators Research, 57(1), 43–41.

Lloyd, C., King, R., Lampe, J., & McDougall, S. (2001). The leisure satisfaction of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 107–113.

Lucas, R. (2007). Long-term disability is associated with lasting changes in subjective well-being: Evidence from two national representative longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 717–780.

McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: subjective wellbeing and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42–65.

McCormick, B., & McGuire, F. (1996). Leisure in community life of older rural residents. Leisure Sciences, 18, 77–93.

Michalos, A., & Kahlke, P. (2010). Arts and the perceived quality of life in British Columbia. Social Indicators Research, 96, 1–39.

Nawijn, J. (2011). Determinants of daily happiness on vacation. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 559–66.

Nawijn, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2011). The effects of leisure activities on life satisfaction: The importance of holiday trips. In I. Brdar (Ed.), The human pursuit of well-being: A cultural approach (pp. 39–53). London: Springer Science + Business Media.

Oswald, A., & Powdthavee, N. (2008). Does happiness adapt? A longitudinal study of disability with implications for economists and judges. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1061–1077.

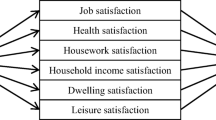

Pagan, R. (2012). Longitudinal analysis of the domains of satisfaction before and after disability: Evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel. Social Indicators Research, 108(3), 365–385.

Pagan, R. (2014a). The contribution of holiday trips to life satisfaction: the case of people with disabilities. Current Issues in Tourism, forthcoming, online first.

Pagan, R. (2014b). How do disabled individuals spend their leisure time? Disability and Health Journal, 7(2), 196–205.

Parr, M., & Lashua, B. (2004). What is leisure? The perceptions of recreation practitioners and others. Leisure Sciences, 26, 1–17.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Reynolds, R. (1993). Recreation and leisure lifestyle changes. In P. Wehman (Ed.), Use ADA mandate for a social change (pp. 2\7-23S). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Rimmer, J., & Rowland, J. (2008). Health promotion for people with disabilities: implications for empowering the person and promoting disability-friendly environments. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine., 2(5), 409–420.

Robinson, J. P., & Martin, S. (2008). What do happy people do? Social Indicators Research, 89, 565–571.

Sirgy, M. (2010). Toward a quality-of-life theory of leisure travel satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 49, 246–260.

Sirgy, M. (2012). The psychology of quality of life: hedonic well-being, life satisfaction and eudaimonia. New York: Springer.

Sirgy, M., Kruger, P., Lee, D., & Grace, B. (2011). How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? Journal of Travel Research, 50, 261–275.

Smith, R. (1987). Leisure of disabled tourists: barriers to participation. Annals of Tourism Research, 14, 376–89.

Terza, J. (1987). Estimating linear models with ordinal qualitative regressors. Journal of Econometrics, 34, 275–291.

Toepoel, V. (2013). Ageing, leisure and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people? Social Indicators Research, 113, 355–372.

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2008). Quantified happiness: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Praag, B., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51, 29–49.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Questions on happiness: Classical topics, modern answers, blind spots. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 7–26). Oxford: Pergammon Press.

Verbeek, M., & Nijman, T. (1992). Testing for selectivity bias in panel data models. International Economic Review, 33(3), 681–703.

Wankel, L., & Berger, B. (1990). The psychological and social benefits of sport and physical activity. Journal of Leisure Research, 22(2), 167–182.

Wilhite, B., & Shank, J. (2009). In praise of sport: Promoting sport participation as a mechanism of health among persons with a disability. Disability and Health Journal., 2, 116–127.

Winefield, A., Tiggemann, M., & Winefield, H. (1992). Spare time use and psychological well-being in employed and unemployed young people. Journal of Occupational and organizational Psychology, 65, 307–313.

Winkelmann, R. (2009). Unemployment, social capital and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 421–430.

Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. In Proc. OECD/HRDC Conference, Quebec, 19–21 March 2000: the contribution of human and social capital to sustained economic growth and well-being (ed. J. F. Helliwell), pp. 65–88. Ottawa: HDRC.

Ye, S., Yu, L., & Li, K. (2012). A cross-lagged model of self-esteem and life satisfaction: Gender differences among Chinese university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(4), 546–551.

Zimmermann, A., & Easterlin, R. (2006). Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce and happiness in Germany? Population and Development Review, 32(3), 511–528.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pagán, R. How Do Leisure Activities Impact on Life Satisfaction? Evidence for German People with Disabilities. Applied Research Quality Life 10, 557–572 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9333-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9333-3