Abstract

There’s something deeply right in the idea that knowledge requires an ability to discriminate truth from falsity. Failing to incorporate some version of the discrimination requirement into one’s epistemology generates cases of putative knowledge that are at best problematic. On the other hand, many theories that include a discrimination requirement thereby appear to entail violations of closure. This prima facie tension is resolved nicely in Jonathan Schaffer’s contrastivism, which I describe herein. The contrastivist take on relevant alternatives is implausible, however, and this then threatens to undermine contrastivism’s anti-skeptical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I use “SH” to denote a radical skeptical hypothesis, one that threatens empirical knowledge globally, as opposed to milder or local skeptical hypotheses, for instance, that this “vase” I seem to see is merely a hologram.

Setting aside Putnam’s (1981) argument that one would not have the concepts to think or express the belief that one is not a BIV. If you’re familiar with that argument, simply stipulate that S has only recently been envatted, and prior to envatment acquired the relevant concepts from causal contact with their referents.

This is only a necessary condition, so the reader may be concerned that I’m neglecting to mention something more substantial that may be on offer by these theorists, perhaps amounting to a discrimination condition. But safety theorists are keen to make sense of the possibility of (non-discriminating) knowledge that radical skeptical hypotheses are false, hence restoring closure, and so any other conditions advocated by these theorists are irrelevant to the point I’m making in the text. I should also point out that, on Williamson’s view, one may in fact have different evidence in the actual world (assuming it to be “normal”—the good case) than one would have in a BIV world, where evidential difference may suggest a capacity to distinguish, but the problem here is that one is not able to distinguish the evidence in the good case from that in the bad one.

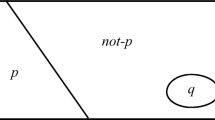

The discrimination requirement is implicit here in that proof and certainty require one to be able to discriminate p from q. In Schaffer (2004a, 150), he characterizes discrimination thus: “s has the capacity to discriminate proposition p from proposition q iff (i) p and q are exclusive, (ii) s’s experience is compatible with p, and (iii) s’s experience is incompatible with q. And s discriminates p from q (exercises the capacity) iff s believes that p rather than q on the basis of s’s capacity to discriminate p from q.” I suppose that we should say: “...to discriminate p’s being true from q’s being true” (because it’s assumed that we can distinguish the propositions themselves), but that’s a small point.

I say “quasi-syllogistic” because with the epistemic operator “know that” the argument is not formally valid, and the fact that at least a few philosophers deny closure suggests that its non-formal validity is an open question.

“Okay, then what kind of knowledge can one derive, through closure, from contrastive knowledge?” The following might be an easy case. I know that I have hands rather than stumps. I know that if I have hands rather than stumps, then I do not have stumps. Therefore, I know that I do not have stumps. But the issue is still somewhat sticky, since Schaffer says that “Moore knows that he has hands rather than stumps,” but “Moore does not know that he has hands rather than vat-images of hands” (2005a, 262). So it must be false that if Moore knows that he has hands rather than stumps, then he knows that he has hands rather than vat-images of hands. Hence there must be something defective about the corresponding closure quasi-syllogism. C1**: Moore knows that he has hands rather than stumps. C2**: Moore knows that if he has hands rather than stumps, then he has hands rather than vat-images of hands. Therefore C3**: Moore knows that he has hands rather than vat-images of hands. And therefore, finally, C2** must be false (because C1** is true and C3** is false). And for many, the falsity of C2** is not obvious (and in fact it seems to be true). (Thanks to an anonymous referee for pointing out this concern upon reading an earlier draft where I highlighted the falsity of C2**—falsity to which Schaffer seems to be committed.) Schaffer simply points out that it is a consequence of his view that “one cannot use the fact that Moore knows that he has hands rather than stumps to infer that Moore knows that he has hands rather than vat-images of hands. The fact that the vat possibility lies outside Moore’s discriminatory range does not entail that the stumps possibility does too” (ibid., 263). Since Schaffer’s resolution of the paradox at least seems to imply the falsity of C2**, one would like to hear more about how C2** can be false. Problematic as this may be—at least it seems not as implausible as claiming the falsity of the original C2 (I know that if I have hands, then I am not a (handless) BIV)—it is not my central dispute with contrastivism. Schaffer (2007) offers further illustrations of the compatibility of closure and contrastivism.

Here’s another version of this claim. Schaffer 2004b says that standard relevant alternatives theories are mysterious, whereas saturation does better: “alternatives enter into the truth conditions via such mechanisms as ‘rather than’—arguments, interrogatives, focusing, and free variables (as serving to saturate the q [alternatives] slot)” (87).

Schaffer notes that some inquiry-guiding questions are based on false presuppositions, from which it simply follows that none of the answers are true. But the “goldfinch or raven?” case need not be one of false presupposition. It may be true that it is either a goldfinch or raven. Still, if for all I know it is a canary, then my ability to rule out its being a raven does not yield knowledge that it is a goldfinch, rather than a raven.

So I’m tempted to say that what Schaffer’s RAT really offers is the following: Dad knows that if it’s either a barn or a farmhouse, then it’s a barn rather than a farmhouse. (Or, worse still, Dad knows (only) that it’s not a farmhouse.) But I’m sure this wouldn’t gain Schaffer’s consent.

As is typical in describing these cases, it is assumed that the BIV possibility is far off. After all, knowledge is factive, and so if (some ordinary empirical) p is true, the BIV possibility is very remote. So we’re imagining a scenario where, if I were a BIV, I would exist in a world where my perceptual experiences are not of goldfinches, canaries, and the like, such that, fully described, it could not be true that there is a bird in my line of vision and that it is a goldfinch.

This sort of issue came up frequently at a recent conference (Linguistics and Philosophy Conference, Aberdeen (UK), May, 2007), in responses both to Schaffer’s paper and to mine. I’ve been insisting here that my criticism is based solely on Schaffer’s RAT, not on his ternary propositional structure. But something seems amiss here. Usually, the point of a RAT is to distinguish relevant from irrelevant alternatives, such that if S can rule out the former, S knows that p. Schaffer’s RAT, on the other hand, builds the relevant alternatives right into the content of what one knows—S knows that p rather than [all the relevant alternatives]. If I am right that Schaffer’s RAT is inadequate because one does not know that p rather than q when there are relevant alternatives not determined by the contextual query, and if one were to amend this oversight by a different account of relevant alternatives, would there be any point in retaining Schaffer’s ternary structure? Having ruled out all the truly relevant alternatives, wouldn’t it make sense to say that S knows that p (period)? This concern explains why, in the main text, I implied at least a couple times that, though my criticisms are not based on Schaffer’s proposal for a ternary knowledge attributing propositional structure, they might have negative implications for that proposal.

Well, there’s luck and then there’s luck. Not all forms of luck preclude knowledge. If I hear a bang and happen to look in the direction of the noise, and then witness a bank robber leaving the bank, my belief that the bank robber jumped into a Toyota is in a sense lucky, since without the loud bang I never would have looked in the right direction. I trust that the reader can distinguish this kind of luck, which does not preclude knowledge, from the kind of luck described in the text.

Among others, Schaffer’s aims are to account for the progress of inquiry and to give substance to the discrimination insights. Schaffer points out that one’s ability to answer the question whether it is a goldfinch or raven is inexplicable if knowledge ascriptions are construed as having binary propositional form (Schaffer 2005a, 244). But what contrastive knowledge does one actually have here? Not that it is a goldfinch rather than a raven, but that it is some kind of yellow bird rather than a raven, and there’s your progress and discrimination.

References

Cohen, S. (2000). Contextualism and skepticism. Philosophical Issues, 10, 94–107.

DeRose, K. (1995). Solving the skeptical problem. The Philosophical Review, 104(1), 1–52. doi:10.2307/2186011.

Goldman, A. (1976). Discrimination and perceptual knowledge. The Journal of Philosophy, 73(20), 771–791. doi:10.2307/2025679.

Kvanvig, J. (2007). Contextualism, contrastivism, relevant alternatives, and closure. Philosophical Studies, 134, 131–140. doi:10.1007/s11098-007-9085-0.

Lewis, D. (1996). Elusive knowledge. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 74(4), 549–567. doi:10.1080/00048409612347521.

McGinn, C. (1984). The concept of knowledge. In P. French, T. Uehling Jr & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Midwest Studies in Philosophy 9, Causation and Causal Theories (pp. 529–54). Mineapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Nozick, R. (1981). Philosophical explanations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pritchard, D. (2005). Epistemic luck. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, truth, and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2001). Knowledge, relevant alternatives and missed clues. Analysis, 61(3), 202–208. doi:10.1111/1467-8284.00295.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Perceptual knowledge derailed. Philosophical Studies, 112, 31–45. doi:10.1023/A:1022590626235.

Schaffer, J. (2004a). Skepticism, contextualism, and discrimination. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research LXIX, 1, 138–155.

Schaffer, J. (2004b). From contextualism to contrastivism. Philosophical Studies, 119, 73–103. doi:10.1023/B:PHIL.0000029351.56460.8c.

Schaffer, J. (2005a). Contrastive knowledge. In T. Gendler, & J. Hawthorne (Eds.), Oxford studies in epistemology, volume 1 (pp. 235–271). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2005b). What shifts? Thresholds, standards, or alternatives? In G. Preyer, & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy (pp. 115–130). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2007). Closure, contrast, and answer. Philosophical Studies, 133, 233–255. doi:10.1007/s11098-005-4545-x.

Sosa, E. (1999). How to defeat opposition to Moore. Philosophical Perspectives, 13, 141–153.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, K. Contrastivism and Lucky Questions. Philosophia 37, 245–260 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-008-9170-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-008-9170-4