Abstract

As they deliver services, organizations have to deal with conflicts over competing and sometimes irreconcilable values, especially at a time when they are facing competitive pressure and diminishing resources. The civicness of organizations expresses itself in how they enable positive interaction over such conflicts between their members. This paper focuses specifically on the relationship between professionals and their managers. By infusing social behaviour with civil values, organizations can contribute to a wider culture of citizenship.

Résumé

Comme fournisseurs de services, les organisations doivent traiter des conflits de valeurs opposées et quelquefois inconciliables, particulièrement lorsqu’elles doivent faire face à une tension de compétition et à des ressources décroissantes. Le civisme des organisations s’exprime dans la manière de mettre en œuvre une interaction positive lors de tels conflits entre leurs membres. Cet article est particulièrement focalisé sur la relation entre les professionnels et leurs managers. En insufflant un comportement social et des valeurs civiles, les organisations peuvent contribuer à une plus large culture des citoyens.

Zusammenfassung

Beim Liefern von Leistungen haben Organisationen Auseinandersetzungen über konkurriende und manchmal unvereinbare Werte zu lösen, speziell in einer Zeit, wenn sie Wettbewerbsdruck und abnehmenden Ressourcen gegenüberstehen. Die civicness von Organisationen drückt sich darin aus, wie sie ein positives Zusammenwirken ihrer Mitgliedern über solche Konflikte ermöglichen. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich speziell auf die Beziehung von Fachleuten zu deren Managern. Indem sie Sozialverhalten mit bürgerlichen Werten durchdringen, können Organisationen zu einer breiteren Bürgerschaftskultur beitragen.

Resumen

Ahora que ofrecen servicios, las organizaciones tienen que afrontar conflictos sobre valores enfrentados y a veces irreconciliables, especialmente en un momento en que sufren presiones competitivas y una reducción de los recursos. Una organización demuestra su civilidad si consigue la interacción positiva de tales conflictos con sus miembros. Este trabajo se centra especialmente en la relación entre los profesionales y sus directores. Inculcando valores civiles al comportamiento social, las organizaciones pueden fomentar una cultura de la ciudadanía más amplia.

摘要

在他们提供服务时,机构不得不处理竞争造成的、有时还包括不可调和的价值观造成的冲突,尤其是面临竞争压力和资源缩减的时候。机构的公民精神表现在它能让机构的成员之间就此类冲突进行积极有益的沟通和互动。本文特别关注专业人士与其主管之间的关系。通过引入以公民价值观为基础的社会行为,机构可以推动公民文化的广泛传播。

ملخص

كما إنهم يقومون بتقديم الخدمات ، يجب على المنظمات أن تتعامل مع النزاعات على التنافس و أحياناً التعامل مع قيم لا يمكن التوفيق بينها، خاصة في الوقت الذين يواجهون الضغوط التنافسية وتناقص الموارد. تمدن المنظمات يعبر عن نفسه في كيفية تمكينهم التفاعل الإجتماعي في مثل هذه النزاعات بين أعضائهم. يركز هذا البحث على وجه التحديد على العلاقة بين المهنيين والمديرين. عن طريق غرس السلوك الاجتماعي والقيم المدنية ، و أن المؤسسات يمكن أن تساهم في توسيع نطاق ثقافة المواطنة.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Not long after I started a new job in the summer of 2007 at the Nijmegen School of Management, one of the senior bureaucrats of my faculty strode into my office and angrily announced that I had violated internal regulations. In fact, since these regulations were legally embedded, I had in fact breached the law. I was at a loss as to what I had done. As it turned out, it concerned my decision to change the design of a course by replacing an exam with a written assignment. Since the course design had been included in the internal regulations, and these were legally binding, we could potentially be sued if a student insisted on taking an exam. The official noted that I should have indicated my desire to make this change by April, when it could have been properly dealt with. My response that I had only started my job in July, that no-one had informed me of internal procedures, and that students were quite happy with the change fell on deaf ears. Later I received an e-mail (cc. to all with a formal responsibility in such matters, which are quite a few people) that as “a RARE exception” (the capitalization is original) I would be forgiven this error of judgment.

What to make of this? My first instinct was to dismiss the man as a petty bureaucrat and regard it as just one more example of an impingement on my autonomy by an ignorant administrator. But it is clear that the perspectives adopted by my “colleague” and myself are influenced by different trade-offs we make. His concern is primarily to uphold the rights of students by maintaining a transparent curriculum, whereas I believe I have the discretionary right to make last-minute adjustments when it is practical to do so. Neither of our positions is inherently unreasonable and inherently connected to the division of labour (“where you stand depends upon where you sit”). But clearly we are not inclined to deal with this difference in trade-offs in a useful manner. He does not make it any easier for me by strutting into my office with the air of a supervisor. Personally, I must admit to the tendency, shared by many colleagues, to regard every non-academic university administrator as an outsider with no understanding of the professional practice of teaching. But, and this is the important point to make here, there is apparently no mechanism, formal, cultural, or otherwise, that helps us to communicate about this in a meaningful way. By “meaningful,” I refer to the sense of a shared understanding of a problem and mutual respect for the other’s position. Here we touch upon the concept of civicness.

The negotiation over trade-offs by professionals and managers within organizations are crucially influenced by the civic quality of organizations. The concept of civicness helps us to discuss civil society without being bound to the traditional conceptualizations, specifically those restricting it to informal communities and volunteering. This is why an analysis of professionals is in a sense the acid test of the concept. That civicness exists in professional contexts is intuitively obvious. After all, it is hard to maintain that love, care, and commitment disappear once people start receiving financial compensation for their labour. Here I will focus primarily on professionals in the public services, such as education and health care.

These professionals are currently under increasing pressure, which has led to a backlash against recently fashionable public management philosophies and its perceived champions, the managers. Yet the problem is more complex than a simple narrative of conflict between professionals and managers would suggest. Competitive pressure and a squeeze in resources have generally made it more difficult for public service providers to balance different values such as equity, efficiency, and quality. This friction between values is, by extension, likely to increase the friction between groups with different positions within the organization. As clients demand better quality and managers cope with shrinking budgets, the potential for conflict grows, since people in different positions will tend to favour a different balance of values. The cleaner will set different priorities than the surgeon; the surgeon different priorities than the hospital managers. The civic quality of organizations is crucial in helping organizations manage such tensions.

Civicness is the quality of institutions, organizations, and procedures to stimulate, reproduce, and cultivate civility. Civility refers to virtues such as commitment to other people, social concern, involvement, responsibility, the ability to restrain aggression in conflicts (particularly relevant in my opening example), and mutual respect. It counters vices such as selfishness, indifference, aggression, and a lack of responsibility. Civility, in these terms, is the ability to express certain values in our relations with other people.

As the traditional position of professionals within organizations diminishes in stature, while simultaneously the balance between competing values is increasingly difficult to maintain, civility becomes more important in containing potential conflict between different members of the organization. By implication, the civic quality of the organization will be increasingly significant to achieve a high level of integration.

Professionals Under Pressure?

Let me develop my argument with a discussion of the position of professionals in the public services. There are various definitions of what it means to be a “professional” (see, e.g., Burrage et al. 1990; Freidson 2001), but definitions generally contain the following elements:

-

A professional has specific knowledge and expertise, based on the application of systematic theoretical principles.

-

The professional belongs to a closed community of people with similar knowledge and expertise. This community is characterized by shared norms and values, institutions for socialization, and regulation.

-

The closed nature of the community is considered legitimate by the wider society within which it operates.

-

Both at the individual level and at the level of their community, professionals are allowed a broad measure of discretionary autonomy to manage their own affairs.

Of course, people with the characteristics mentioned above date back to the Mesopotamian scribes, but the rise of professional groups is particularly associated with the process of modernization. In a society characterized by increasing specialization, sociologists began to discern specific groups of occupations that achieved sufficient social status to secure a high degree of self-regulation for themselves. The medical profession is the typical example: its members have specialized knowledge that most people lack; they share certain cultural codes, symbolized by swearing the Hippocratic Oath; limited entry to their community is maintained by medical schools with restricted access; individual members have the freedom to make highly personalized judgments in their daily practices; traditionally their community regulates its own affairs, including failures of judgment; and, the rest of society has generally accepted this state of affairs, even if the legitimacy of traditional professions has over time diminished.

Perceptions of professionals in the public debate have varied strongly. According to some, professionalism is inherently (functionally) connected to the nature of particular services. At the other extreme stands the view that professions are no more than the institutional outcomes of conflict that protect the position of dominant groups. Such a political perspective inspired the wide denouncement of professionals during the 1970s. Among the best-known criticisms is Illich’s assertion that professionalism is simply a cover for attempts to monopolize and commodify knowledge, robbing citizens of the power to actively solve their own problems (Illich et al. 1977). Not only do professional methods encourage dependency among clients, but professionals also have an interest in keeping their clients in a state of dependency and may be suspected of actively maintaining it.

The criticism of professionals contributed to the support for public sector reforms, collectively known as the New Public Management (NPM). Although these have often been presented as a coherent philosophy, it is more accurate to describe them as a collection of prescriptions for administrative reform with a focus on output-based performance measurement and competition (McLaughlin et al. 2006; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004). When NPM was first launched, it was regarded as a liberating philosophy that would hold public organizations accountable and offer citizens protection from bias and incompetence. However, how NPM affects professionals is rather ambiguous (Trommel 2006). On the one hand, it has underlined the need for decentralized decision-making and autonomy, which can be seen as favouring professionals. On the other hand, and this is the interpretation stressed in much of the literature on professionalism, NPM also emphasizes output control and performance measurement, which potentially diminish professional autonomy when output is defined and measured in detail.

Indeed, a concrete result of NPM-inspired reforms has been that professionals have been brought under stricter control by the organizations in which they operate. One must be careful in making sweeping statements, since there is still a lack of broad and systematic research in this area—and there is some evidence to suggest that broad organizational reforms have only a limited effect on professional practice (e.g., Honingh and Karsten 2007). Where they occur, the reforms entail performance measurement and stricter control over the type of activities that professionals should concentrate on. The extremities of such measures can be bizarre. There is the example of a domiciliary care worker who came to cook lunch for a client at the appointed hour, but was asked to do some shopping instead. When she emerged from the house, she was spotted by an auditor who argued it was a breach of contract—it was lunch hour, not shopping hour—and then had the contract with the provider terminated (as told by Hardy and Wistow 1998).

Relations Between Professionals and Managers

The reforms have therefore given rise to a new wave of criticism, this time siding with the professionals and directed against NPM’s champions, the managers. Sometimes the criticism has been overly sentimental, portraying professionals as innocent victims of managers’ influence. Professionalism, like managerialism, contains elements of ideology. Yet there are various reasons why, empirically, the opposition between professionals and managers should not be overstated.

To begin with, the distinction between professionals and managers is unclear and increasingly blurred. For a start, it is in practice simply difficult to pin down specific groups within organizations. Even small ones tend to be composed of various layers and subunits, ranging from street-level workers through various strata of middle management to top management. The further one gets away from the extremes, the more difficult it becomes to identify positions, especially as everyone tends to be called a manager these days. Empirical evidence suggests that the division of labour is blurring, with professionals picking up more management responsibilities and managers engaging more closely with service delivery (Noordegraaf 2008).

Furthermore, the available evidence shows that the extent to which NPM-inspired reforms has trickled through differ greatly between sectors, and that the relationship between managers and professionals differs accordingly (Ackroyd et al. 2007). It is not necessarily an oppositional relationship. There are in fact policy fields where they operate as allies, cooperating to deal with common trends such as mergers and privatization. It has led Noordegraaf (2008) to argue in favour of contextualizing their relationship on the basis of further empirical evidence, rather than making prior assumptions about it. Rather than regarding each other as opposites, managers and professionals can engage in constructive coalitions. It is clear that the nature of actual relationships between managers and professionals varies greatly and so does the level of friction between them.

Moreover, a development that complicates a supposed management–professional opposition is that nowadays many occupations have claimed professional status. As far back as the 1960s, Wilensky spoke of “the professionalization of everyone” (Wilensky 1964). Of late, people in lines of work that were previously considered too undefined or low-skilled have made attempts to qualify for the prized label. For instance, in medicine, the icon of professionalism, professional boundaries are increasingly dynamic, with nurses and assistants taking over duties from traditional professionals (Nancarrow and Borthwick 2005). Interestingly, the occupations claiming professional status include the managers themselves. They have their own curricula and degrees, their own networks and conventions, and increasingly identify themselves as a separate group independent from the policy fields in which they are active (Noordegraaf 2008).

The legitimacy of new professions such as the managerial one is disputed. For example, the famous management guru Henry Mintzberg has accused management schools of training people out of context and argued that the common MBA training method of learning from case studies is not experience, but voyeurism (Mintzberg 2004). One could interpret the claim to professionalism as just another weapon in the competition over scarce resources, with all occupations scrambling for an upgrade of their status. Then again, it is also indicative of a broader development towards a society where expert knowledge is no longer confined to a select handful of occupations and where classical status groups no longer have the legitimacy to uphold their privileged status. It has given experts cause to reconsider the concept of professionalism, a discussion to which I will return below.

To avoid misunderstandings: to question the reasoning behind the current criticism of managers is not to deny current problems in the public services, such as high pressure and loss of autonomy among professionals. Even if it can be overstated, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that these problems exist in a number of policy fields (Duyvendak et al. 2006). The question is: what kind of perspective is productive in analyzing these problems? It is probably not one that rests upon a narrative of heroes and villains. Not long ago, managers were the supposed champions of reinvigorated public services. Now they have been revealed as traitors to the cause. At some later stage, they will no doubt be rehabilitated. An analysis of civicness in organizations must go beyond the current fashions and consider how tensions between different organizational members, which nearly always exist and which have been documented from the earliest beginnings of organizational analysis, can be dealt with in a civil way; that is, on a basis of mutual respect.

Bringing Managers Back in

What is mutual respect? At the very least, one would imagine, it implies recognition of the other’s existence as a fellow citizen. Yet here we run into a theoretical obstacle in resolving the perceived tensions between professionals and managers. Much criticism of managerial influence on professionals tends to focus primarily on managerialism and not on managers. As an illustration, let me take Lipsky’s classic analysis of street-level bureaucrats (would they be called street-level professionals today?). In this inspiring book, Street-Level Bureaucracy, he shows how workers face pressure from various directions, both from clients and managers (Lipsky 1980). They invent methods to deal with these pressures, sometimes these are generally accepted methods (e.g., keeping spare capacity to deal with special cases, sometimes they are an outright violation of anything we can define as civic—e.g., deliberately humiliating clients). This is to regain control, or, to be more precise, it is about reversing a lack of control. Otherwise the dispositions of the street-level bureaucrats—what they positively want—remain rather obscure. Clients are only observed in terms of their outward behaviour, as in how they put bureaucrats under pressure. Managers are faceless and only described in terms of demands, push, and pull. Notwithstanding the high appeal and merits of Lipsky’s analysis, it leaves no room for any solution except that street-level bureaucrats are relieved from outside pressure—and one of his starting assumptions is that such pressure is inevitable.

To some extent this is a problem inherent in many studies of professionalism. In the words of Tilly (2005), they adopt a dispositional perspective, one that explains action on the basis of the orientations of the subject—in this case the professional. Orientations can be conceptualized as preferences or rationalities; action is determined by the incentives related to those orientations. Many critics of managerialism only discuss managers in terms of these incentives. In other words, they do not discuss the interaction between managers and professionals, but managerialist influences on professional behaviour. More specifically, they concern forces of control. Managers and their motivations are largely absent, except in a highly stylized form.

At its worst, this leads to a conceptualization of organizations as pineapples: a primary process surrounded by an unwholesome bureaucratic peel. From such a perspective, managerial layers are at best a necessary evil. Such a conceptualization not only disregards the empirical developments discussed earlier, but also leads the discussion into a conceptual dead-end. If our objective is to develop a theory of civicness in organizations, then the conceptualization should at least leave room for mutual respect—in other words, the managers should be brought back in, not as environmental influences, but as fellow citizens with whom professionals and others interact. In what follows I will argue that this calls for a relational view of interaction within organizations.

Bringing Managers into Focus

As argued above, conceptually, discussions of the current problems of professionals tend to ignore the managers, focusing on the mechanisms rather than the person. This, as I hope to demonstrate, stands in the way of developing a theory of civicness in organizations. Suppose, though, that we do bring the managers into focus, not as management tools or as abstract forces, but as individuals. What kind of people are they?

Are they self-interested Machiavellians bent on exploiting other workers for their own ambitions? In the context of public services, this would confirm to the image of the self-aggrandizing bureaucrat (Niskanen 1971). Are they basically good, but misguided men and women who impose strategies and systems without sufficient knowledge of their practical consequences? That would be close to Scott’s analysis of state failure, where the worst planning disasters (e.g., the collectivization of farm land or urban planning in the style of les banlieux) are the result of flawed visions driven by the best of intentions (Scott 1998). Or is the manager them self a victim of the system, an unwilling perpetrator of NPM reforms and an implicit ally of professionals? This is what Noordegraaf (2008) has recently suggested in his call for a rehabilitation of managers. Clearly, these types are analytical constructs and real people are potentially all of the above.

One study in which these different types come together is Julien Le Grand’s analysis of the motivations of professionals, managers, and clients implicit in public policies (Le Grand 2003). Le Grand identifies four ideal-typical people, each with a particular kind of motivation: Knights are people who are predominantly altruistic, working for the common good; Knaves, by contrast, are people who base their actions purely on self-interest; Pawns are passive victims of circumstance; whereas Queens are active citizens who take matters into their own hands. This typology neatly summarizes more complex philosophical positions. As one might expect, Le Grand’s evidence shows that clients or professionals, clients or managers, do not as a rule conform to any one of these stereotypes. They are just like real people: they differ among themselves and even individuals do not consistently behave in a self-interested or altruistic, passive or active way.

On the one hand, it seems rather obvious. Any decent novel will tell you that all people have “good” and “evil” in them. On the other hand, the difficulty is to contextualize these different qualities without losing the analytical poignancy of the types. For, obvious as it may be, there is as yet no generally applicable conceptualization of this essential ambiguity in people’s disposition. It is more usual to assume a more singular disposition—usually a knavish one—and then proceed from there. Different orientations then become the “other” category or are simply redefined as a particular type of knavishness. For example, Mother Teresa’s charitable works can be interpreted as an effort to secure her own salvation. Such analytical constructions are useful devices because we usually know little about actual motivations. It is impossible to look into the human heart.

Civility: Mobilizing the Knights

Fortunately, there is no need (at least not here) to delve deeper into the issue of inner motivation. When we speak of civility, then being a knight or knave is conceptually not about inner motivation, but about conformity to certain values and norms. For example, non-aggression is a virtue because we define it as such. In other cultures, starting a fight may be construed as a sign of respect. I started this article by describing the dilemma between my orientation as a professional and my orientation as an individual human being. The “individuality” refers not to personality, but to the status of a fellow citizen who is entitled to be treated with respect by other citizens, regardless of individual traits. In other words, it refers to an orientation based on a set of social norms and values which is (at least theoretically) different from those norms and values belonging to the professional community.

In practice, these sets of norms and values overlap, but not always. Actions resulting from a professional orientation may be perceived as going against what is considered fair according to broader cultural norms. Consider the lawyer defending a proven criminal: professionally, their efforts to diminish the criminal’s sentence are professionally laudable, but they are unlikely to rouse our sense of justice (which is, in fact, one of the great dilemmas of legal systems). Stereotypical images of professionals tend to associate professions with certain civic orientations and their social standing differs between professions and between national cultures. For example, the status of judges varies widely between countries, but they are invariably ranked higher on the social scale than estate agents and stockbrokers.

Then again, in some professions they can strengthen one another, especially in so-called “human services.” Consider, for instance, civility in its crudest form: the mannerisms of using polite phrases, addressing people by their surnames, shaking hands. It is nice when the doctor who is competent at mending bones is simultaneously a civil person. By definition we wish for everyone to be kind, but perhaps especially when we feel weak or ignorant, as can easily be the case when dealing with professionals. After all, what makes the professional what they are inherently creates some form of dependence, even if it is unintended. Better then to be treated as an equal, if only through a sense of shared humanity. Indeed, it goes further. Some definitions of service quality can hardly be separated from civil values. This is especially the case in personal services, where being cared for is often an intimate experience where the line between professional and personal interaction is very thin, at least in the perception of clients. In personal services, the link between civility and professional behaviour is a close one.

Such civil values expressed in professional behaviour have received a lot of attention in the recent debate, in which professionals are sometimes presented as inherently committed and caring. In a theory of civicness, such an assumption must be discarded. If institutions can encourage civil behaviour, it is also possible that they do not encourage such behaviour; indeed, that they elicit uncivil behaviour. If not, the concept of civicness would be redundant. Theoretically, one must then suppose that professionals can be both knightly and knavish as citizens. A theory of civicness must therefore discard predefined notions of professionals (or anyone else) as selfish, power-hungry, caring, or loving. Rather, we should consider how such dispositions are shaped. Hirschman (1982) has argued that, rather than assuming a fixed set of preferences, we should assume that initial preferences can be changed through experience, which leads to changes on the demand side and not necessarily to changes in supply. For instance, we may cast a vote during elections in the belief that this will bring us happiness, but having been disappointed over and over again, we may simply stop voting at some point. This is intuitively obvious, but difficult to theorize. Certainly one of the potential benefits of discussions on civicness is that they can contribute to theory-building in this direction.

Essentially, then, civicness in organizations can be conceptualized as the conflation of roles: the role of a professional in an organizational capacity and the role of a fellow citizen. In organizations with a high civic quality, the behaviour of professionals expresses civil values. In organizations with a low civic quality, the behaviour of professional is characterized by a lack of civility.

Civicness and Integration

The effects of public sector reforms can be redefined in their effects on the expression of civil values. Whether or not such reforms have diminished the overall quality of services is difficult to judge on the basis of existing evidence. However, what is clear is that they tend to reduce the scope for displaying civil qualities. As an example, think of a doctor, who treats his patients with what patients consider undue speed; who openly classifies them in terms of professional categories rather than holding up at least the pretence of individual judgment; who grants his patient only the minimum necessary treatment. It is possible that this doctor is simply an ill-tempered swine, but it is more likely that they are responding to the need to handle a large workload within the allotted time and responding to organizational requirements of efficiency.

In a fundamental sense, this can be regarded as a clash of values. The values of managerialism are systemic, defining aggregate targets. These are translated into requirements at the individual level, but they remain individualized aggregate values, not personal values, and civility is all about relations at the personal level. In service delivery dominated by the need for efficiency, values such as commitment and mutual respect are likely to suffer. Lipsky’s street-level bureaucrats use control strategies because they must ration supply. They are in a bind that leaves little room for civility. If anything, it forces them to reinforce power differences and ignore the fact that their clients are human beings.

Yet to some extent this is unavoidable, because there is a broader range of values to be taken into account when organizing service delivery. An analysis of professional service delivery cannot be based on the primary process alone. Organizations constitute an entity that integrates the various types of labour necessary to provide a specific type of product or service. Never mind whether some of these have more exclusive knowledge than others: they are all necessary. A hospital needs good cleaners and bookkeepers as well as good heart surgeons. The combination of different positions reflects the different goals that an organization needs to balance; not simply the quality of ultimate delivery, but also an efficient use of scarce resources, equality of access, protection from favouritism and arbitrary judgement, and long-term sustainability. Depending on position, one member of the organization will tend to stress certain values over others. It means that, to some extent, the interests of different participants reflect basic dilemmas in the provision of public services. All services have inherent dilemmas, but public services the more so since demand often has no natural cap (in other words, resources are always insufficient) and definitions of quality are more complex. Given such manifold and competing interests to be satisfied, it is unavoidable that there is friction within organizations.

There are several ways of dealing with such friction. It is partly a question of devising clever procedures, methods, and systems. By virtue of their design, some organizations manage to achieve more satisfactory overall outcomes (and therefore lower levels of friction) than others. Partly, it is a political struggle over which values should receive priority. But dealing with conflict also calls upon “softer” values such as commitment and mutual respect. In its most visible form, this can be common courtesy: simple politeness can go a long way in dampening conflict. But it goes further, in expressing a basic attitude towards others that does not derive from their organizational position. Instead, it draws upon notions of citizenship in which people are equals, regardless of whether they are manager, cleaner, or doctor.

All this points to another potential benefit of civicness, in addition to its direct relationship with the quality of services: by preventing conflict and facilitating decision-making among staff members with different interests, the expression of civil values is a mechanism that contributes to the integration of the organization. And if that is the case, then the question is under what conditions organizations encourage civil behaviour among professionals, managers, and clients? and when they discourage civility? Lipsky’s grim depiction of street-level bureaucracies is a typical example of the latter. If we are to truly understand civicness, we should be able to explain both the uncivil and civic qualities.

Members of the organization, professionals and managers alike, must learn to deal with friction both within different sets of values and between them. While such friction is inevitable, there are various developments that have made it more likely, since public service delivery has generally become more complex. Many services are delivered through a welfare mix that combines the mechanisms of hierarchy, competition, and community (Brandsen et al. 2005; Evers and Laville 2004). Providers operate in complex networks where various parties are jointly responsible for the ultimate delivery (Brandsen and Van Hout 2006). An increasing number of organizations are becoming hybrid in nature. As a result, value clashes are ever more likely and, by implication, so is the potential for conflict between members of the organization in different positions.

Of course, organizations will try to find a new balance between different values and some organizations will be better at this than others. However, as Evers (2005) has noted, although one can theoretically argue in favour of a perfect balance between contradictory values, it is more realistic to expect that such a balance does not exist. The real issue is how to deal with a situation of permanent and shifting imbalances. In addition to other mechanisms, such as formal procedures for conflict resolution, the civic quality of organizations is an important means of dealing with the resulting tensions. Given current trends in the public services, it is likely to be increasingly tested.

Redefining Professionalism?

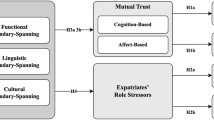

Finally, it is interesting to consider how this interpretation of civicness reflects back upon common conceptualizations of professionalism described above. In light of the increasing complexity of service delivery, Noordegraaf (2007) calls for a reinterpretation of the concept of professionalism. Noordegraaf (2007) identifies three perspectives on the concept, which can be roughly described as follows: “pure professionalism” advocates a return to the classical professions and rejects the “new” professions; “situated professionalism” expands the concept of professionalism to include experts working in an organizational context; and “hybrid professionalism” sees professionals as reflective practitioners who construct and apply professionalism to symbolically structure their relations with the outside world. This third interpretation is a direction of thinking that is interesting with regard to civicness and is in line with broader discussions in the sociology of professions (Davies 2006). It sees professionalism as essentially relational, a way of sense-making in the interaction with others.

This reconceptualizes professionalism in a context where the ability to legitimize difficult choices has severely diminished and the symbolic control afforded by the classical professions is eroding. It becomes “a search for coping with trade-offs in economised but ambiguous times” (Noordegraaf 2007, p. 778). This reinterprets the concept of professionalism, not with reference to the status positions of closed occupations and standardized knowledge, but to its function in offering guidance for complex decisions and in creating communities that symbolically legitimize these decisions. Classic professionalism offered ways to deal with difficult decisions through shared scripts, institutionalized codes of practices. Where the ever more complex and transforming organizational contexts no longer allows these scripts to function effectively, as may be the case in the public services, it calls for different ways of reaching agreed-upon principles to deal with trade-offs.

The fading distinction between professional and managerial positions is an expression of this, with professionals taking on more managerial tasks and managers engaging more with the issues of professionals. This is creating new professions, not in their classical form, but as more flexible ways of coping with a more complex environment. This casts a different light on how recent public sector reforms have affected relations within organizations. On the one hand, these have created pressures that put professionals and managers alike in a bind. On the other hand, they have also provided the means by which occupational boundaries can be overcome and the internal frictions within organizations can be jointly addressed. The managers’ problems become the professionals’ and vice versa. The effects on internal relations are therefore equally ambiguous: they create the potential for more opposition between different occupational groups, but they also offer opportunities for overcoming traditional boundaries. The civic quality of the organization will help to determine whether it is one or the other.

Conclusion

As they deliver services, organizations have to deal with competing and sometimes irreconcilable values, increasingly so due to recent reforms in the public services. Public services have to be efficient, high-quality, accessible, transparent, and delivered with a smile. It means that the organizations in question will be the arena for various potential conflicts, since their members will differ in terms of the values that they emphasize. This is logical and even desirable. We expect the hospital manager to worry about cost containment, but most people prefer the doctors who treat them to be more concerned with quality. At a higher level of analysis, differentiation allows the representation of different interests within an organization. Yet that calls for powerful mechanisms of integration.

The ultimate trade-offs in service delivery will be controversial and open to continual renegotiation. The civicness of the organization expresses itself in how the organization enables positive interaction over such choices. By infusing social behaviour with civil values, the organization builds upon and contributes to a wider culture of citizenship. This is important for the viability of an organization to further coordinate progressive social action in line with broader developments in society.

References

Ackroyd, S., Kirkpatrick, I., & Walker, R. M. (2007). Public management reform in the UK and its consequences for professional organization: A comparative analysis. Public Administration, 85(1), 9–26.

Brandsen, T., Van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9/10), 749–765.

Brandsen, T., & Van Hout, E. (2006). Co-management in public service networks: The organisational effects. Public Management Review, 8(4), 537–549.

Burrage, M., Jarausch, K., & Siegrist, H. (1990). An actor-based framework for the study of the professions. In M. Burrage & R. Torstendahl (Eds.), Professions in theory and history: Rethinking the study of the professions (pp. 203–225). London: Sage.

Davies, C. (2006). Heroes of health care? Replacing the medical profession in the policy process in the UK. In J. W. Duyvendak, T. Knijn, & M. Kremer (Eds.), Policy, people and the new professional (pp. 137–151). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Duyvendak, J. W., Knijn, T., & Kremer, M. (2006). Policy, people and the new professional: An introduction. In J. W. Duyvendak, T. Knijn, & M. Kremer (Eds.), Policy, people and the new professional (pp. 7–16). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Evers, A. (2005). Mixed welfare systems and hybrid organizations: Changes in the governance and provision of social services. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9/10), 737–748.

Evers, A., & Laville, J. L. (2004). Social services by social enterprises: On the possible contributions of hybrid organizations and a civil society. In A. Evers & J. L. Laville (Eds.), The third sector in Europe (pp. 237–255). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism: The third logic. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hardy, B., & Wistow, G. (1998). Securing quality through contracts? The development of quasi-markets for social care in Britain. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 57(2), 25–35.

Hirschman, A. O. (1982). Shifting involvements: Private interest and public action. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Honingh, M. E., & Karsten, S. (2007). Marketization in the Dutch vocational education and training sector; Hybrids and their behaviour. Public Management Review, 91(1), 135–143.

Illich, I., Zola, I. K., McKnight, J., et al. (1977). Disabling professions. London: Boyards.

Le Grand, J. (2003). Motivation, agency and public policy: Of knights and knaves, pawns & queens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell Sage.

McLaughlin, K., Osborne, S. P., & Ferlie, E. (2006). New public management: Current trends and future prospects. London: Routledge.

Mintzberg, H. (2004). Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. Harlow, UK: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Nancarrow, S. A., & Borthwick, A. M. (2005). Dynamic professional boundaries in the healthcare workforce. Sociology of Health & Illness, 27(7), 897–919.

Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Chicago: Aldine.

Noordegraaf, M. (2007). From “pure” to “hybrid” professionalism: Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration and Society, 39(6), 761–784.

Noordegraaf, M. (2008). Professioneel bestuur. The Hague: Lemma.

Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public management reform (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tilly, C. (2005). Trust and rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trommel, W. (2006). NPM en de wedergeboorte van het professionele ideaal. B&M, 33(3), 137–158.

Wilensky, H. (1964). The professionalization of everyone. American Journal of Sociology, 70(2), 137–158.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Brandsen, T. Civicness in Organizations: A Reflection on the Relationship Between Professionals and Managers. Voluntas 20, 260–273 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9090-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9090-3