Abstract

Expatriates typically perform boundary-spanning to address challenges related to functional, linguistic, and cultural variations within multinational enterprises (MNEs), which in turn influences their relationships with host-country employees. Integrating social capital and role theory perspectives, this study explores the relational dynamics between expatriates and host-country employees by developing a novel theoretical framework that examines the double-edged effects of expatriates’ boundary-spanning. We propose that expatriates’ boundary-spanning nurtures mutual trust between expatriates and host-country employees, further facilitating expatriates’ identification with subsidiaries and host-country employees’ identification with MNEs. On the other hand, we propose that boundary-spanning increases expatriates’ role stressors, causing expatriates’ emotional exhaustion and outgroup categorization by host-country employees. We further categorize expatriates’ boundary-spanning into three types (functional, linguistic, and cultural) and theorize about their varying effects on the cognitive and affective bases of mutual trust and on role stressors. With data from 177 expatriate–host-country coworker dyads in Chinese MNEs, our double-edged framework is generally supported. Our findings suggest that cultural boundary-spanning exhibits the strongest double-edged effect, while functional boundary-spanning shows asymmetric effects, with negative outcomes surpassing positive ones, and linguistic boundary-spanning demonstrates the weakest effect. This study offers realistic and comprehensive insights into expatriates’ boundary-spanning, particularly in expatriate–host-country employee relationships.

Plain language summary

In the field of global business, firms often dispatch workers overseas to their foreign branches. These workers, referred to as expatriates (employees living and working outside their home country), are vital in connecting the main office and the foreign branch. They accomplish this through “boundary-spanning” activities (actions that involve communication and coordination across diverse cultures and organizational practices). While earlier studies have highlighted the positive aspects of boundary-spanning, such as creating social networks and knowledge transfer, there is a lack of understanding about potential negatives, like stress and burnout. This research aims to investigate both the positive and negative impacts of expatriates’ boundary-spanning on their relationships with local employees.

The study used three datasets collected in 2022. The initial two datasets were utilized to create a scale to measure boundary-spanning, while the third dataset was the primary focus, comprising 177 pairs of expatriates and local coworkers from the energy engineering sector in various Asian countries. The research employed a combination of questionnaires and online surveys to collect data on the expatriates’ boundary-spanning activities and their effects on trust, stress, and workplace relationships.

The research discovered that boundary-spanning can indeed cultivate trust and a sense of belonging among expatriates and local employees, which is beneficial for the firm. However, it also unveiled that expatriates who participate in boundary-spanning activities might experience role stress, leading to emotional exhaustion and potentially being perceived as outsiders by local staff. The study suggests that while boundary-spanning can build valuable social capital (networks of relationships among people), it also carries risks that need to be managed.

In conclusion, the study offers a more balanced perspective of expatriates' boundary-spanning by emphasizing both its benefits and challenges. It proposes that firms should support expatriates in their boundary-spanning roles by providing clear job responsibilities and resources to manage stress. The findings have implications for multinational firms aiming to enhance their international operations and for expatriates striving to succeed in their overseas assignments. The potential impact of this research is significant, as it can assist firms in better preparing and supporting their expatriate employees, leading to more effective international collaboration and knowledge sharing.

This text was initially drafted using artificial intelligence, then reviewed by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Résumé

Les expatriés effectuent généralement le dépassement de frontières (Boundary-spanning) afin de relever les défis liés aux variations fonctionnelles, linguistiques et culturelles au sein des entreprises multinationales (Multinational Enterprises - MNEs), ce qui influence à son tour leurs relations avec les employés du pays d'accueil. Intégrant la perspective du capital social et la théorie des rôles, cette recherche explore la dynamique relationnelle entre les expatriés et les employés du pays d’accueil en développant un nouveau cadre théorique qui examine les effets à double tranchant du dépassement de frontières des expatriés. Nous proposons que le dépassement de frontières des expatriés nourrisse la confiance mutuelle entre les expatriés et les employés du pays d'accueil, facilitant ainsi l'identification des expatriés aux filiales et celle des employés du pays d'accueil aux MNEs. D'autre part, nous proposons que le dépassement des frontières augmente les facteurs de stress liés aux rôles des expatriés, provoquant un épuisement émotionnel des expatriés et une catégorisation hors groupe par les employés du pays d’accueil. Nous catégorisons en outre le dépassement de frontières des expatriés en trois types (fonctionnel, linguistique et culturel), et théorisons leurs impacts variables sur les bases cognitives et affectives de la confiance mutuelle et sur les facteurs de stress liés aux rôles des expatriés. Les données recueillies auprès de 177 dyades d'expatriés et de collaborateurs du pays d'accueil dans des MNEs chinoises confirment globalement notre cadre théorique à double tranchant. Nos résultats suggèrent que le dépassement de frontières culturelles présente l’impact à double tranchant le plus fort, tandis que le dépassement de frontières fonctionnelles présente les impacts asymétriques, avec les effets négatifs dépassant les positifs, et que le dépassement de frontières linguistiques démontre l’impact le plus faible. Cette recherche offre une compréhension réaliste et complète sur le dépassement de frontières des expatriés, plus particulièrement sur les relations entre ces derniers et les employés du pays d’accueil.

Resumen

Los expatriados suelen realizar ampliación de fronteras para abordar los retos relacionados con variaciones funcionales, lingüísticas y culturales en las empresas multinacionales (EMN), esta ampliación a su vez influencia sus relaciones con empleados del país anfitrión. Integrando las perspectivas del capital social y la teoría de los roles, este estudio explora la dinámica relacional entre los expatriados y los empleados del país anfitrión mediante el desarrollo de un novedoso marco teórico que examina los efectos de doble filo de la ampliación de fronteras (boundary-spanning en inglés) de los expatriados. Proponemos que la ampliación de fronteras de los expatriados fomenta la confianza mutua entre los expatriados y los empleados del país anfitrión, facilitando aún más la identificación de los expatriados con las filiales y la identificación de los empleados del país anfitrión con las multinacionales. Por otro lado, proponemos que la ampliación de fronteras aumenta los factores estresantes de los expatriados, lo que provoca su agotamiento emocional y el ser categorizados como grupo externo por parte de los empleados del país anfitrión. Además, clasificamos la ampliación de fronteras los expatriados en tres tipos (funcionales, lingüísticos y culturales) y teorizamos sobre sus diferentes efectos en las bases cognitivas y afectivas de la confianza mutua y en los estresores de rol. Con datos de 177 díadas expatriados-país anfitrión-trabajadores en empresas multinacionales chinas, nuestro marco de doble filo se ve generalmente respaldado. Nuestros resultados sugieren que la ampliación de las fronteras culturales muestra el efecto de doble filo más fuerte, mientras que la ampliación de las fronteras funcionales muestra efectos asimétricos, con resultados negativos que superan a los positivos, y la ampliación de las fronteras funcionales muestra efectos asimétricos, con resultados negativos que superan a los positivos.

Resumo

Expatriados normalmente ultrapassam fronteiras para enfrentar desafios relacionados com variações funcionais, linguísticas e culturais em empresas multinacionais (MNEs), o que por sua vez influencia suas relações com funcionários do país anfitrião. Integrando as perspectivas do capital social e da teoria dos papeis, este estudo explora a dinâmica relacional entre expatriados e funcionários do país anfitrião, desenvolvendo um novo modelo teórico que examina os efeitos de dois gumes da ultrapassagem de fronteiras por expatriados. Propomos que a ultrapassagem de fronteiras por expatriados alimente a mútua confiança entre expatriados e funcionários do país anfitrião, facilitando ainda mais a identificação de expatriados com as subsidiárias e a identificação dos funcionários do país anfitrião com MNEs. Por outro lado, propomos que a ultrapassagem de fronteiras aumenta os fatores de stress do papel de expatriados, causando exaustão emocional de expatriados e categorização externa por parte de funcionários do país anfitrião. Classificamos ainda a ultrapassagem de fronteiras por expatriados em três tipos (funcional, linguístico e cultural) e teorizamos sobre seus diversos efeitos nas bases cognitivas e afetivas da confiança mútua e fatores de stress do papel. Com dados de 177 díades expatriado-colega de trabalho do país de acolhimento em MNEs chinesas, nosso quadro de dois gumes é geralmente suportado. Nossas descobertas sugerem que a ultrapassagem de fronteiras culturais apresenta o efeito de dois gumes mais forte, enquanto a ultrapassagem funcional de fronteiras mostra efeitos assimétricos, com resultados negativos superando os positivos, e a ultrapassagem de fronteiras linguísticas apresenta o efeito mais fraco. Este estudo oferece insights realistas e abrangentes sobre a ultrapassagem de fronteiras por expatriados, particularmente nas relações entre expatriados e funcionários do país anfitrião.

摘要

外派员工经常进行边界跨越 ,以应对跨国企业(MNE)中功能、语言和文化差异的相关挑战 ,进而影响他们与东道国员工的关系。本研究整合社会资本与角色理论视角 ,构建针对外派员工边界跨越双刃剑效应的创新理论框架 ,以探讨外派员工与东道国员工之间的关系动态。我们认为外派员工的边界跨越会促进他们与东道国员工之间的相互信任 ,进而加强外派员工对子公司的认同和东道国员工对MNE的认同。然而 ,我们也认为边界跨越会增加外派员工的角色压力 ,导致外派员工的情绪耗竭 ,并使他们被东道国员工视为外群体。我们进一步细分外派员工边界跨越的三种类型(功能型、语言型和文化型) ,并从理论层面探讨这些类型如何以不同方式影响基于认知和情感的相互信任以及角色压力。基于来自中国MNE的177对外派员工与东道国同事的配对数据 ,我们的双刃剑效应框架总体上得到了支持。研究结果表明 ,文化型边界跨越展现出最强的双刃剑效应 ;功能型边界跨越显示出不对称效应 ,其负面影响超过正面影响;而语言型边界跨越的双刃剑效应最弱。这项研究为理解外派员工的边界跨越提供了实际而全面的洞察 ,尤其是在他们与东道国员工关系方面。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In international business (IB) research, boundary-spanning refers to a set of inter- and intraorganizational communication and coordination activities aimed at enhancing integration amid a wide range of cultural, institutional, and organizational differences in multinational enterprises (MNEs) (Schotter et al., 2017). MNEs often rely on expatriates to execute boundary-spanning (Au & Fukuda, 2002; Yang et al., 2022) due to their cultural and language skills (Barner-Rasmussen et al., 2014) and their ability to transfer explicit and tacit knowledge between clusters (Harzing et al., 2016). When expatriates are assigned to foreign subsidiaries, their boundary-spanning helps MNEs address the challenges of reconciling variations in language, culture, and behavioral norms worldwide (Au & Fukuda, 2002) and of establishing a consistent corporate strategy (Meyer et al., 2020).

As such, IB research often emphasizes a positive view of expatriates’ boundary-spanning, with a prominent focus on utilizing social capital theory to explain this advantage. This theory proposes that the social relationships expatriates create through boundary-spanning activities are considered “social capital” from which individuals and organizational units can gain economic and relational benefits (Kostova & Roth, 2003). Studies employing this theoretical lens have linked the boundary-spanning of globally mobile employees (e.g., expatriates) to positive outcomes, such as improved adjustment and performance (Liu & Shaffer, 2005), knowledge-sharing (Mäkelä, 2007), and inter- and intraunit connections (Reiche et al., 2009). In contrast, research outside the IB field demonstrates that boundary-spanning may also lead to negative outcomes, such as role overload (Wang et al., 2019) and role stress (Stamper & Johlke, 2003). Role theory, which states that social roles shape and influence individuals’ behavior (Anglin et al., 2022), is commonly employed to explain these adverse effects.

In this study, we integrate both social capital theory and role theory to explore the outcomes of expatriates’ boundary-spanning. Given that successful boundary-spanning relies on collaboration with host-country employees (Hsu et al., 2022), we mainly examine its impact on expatriate–host-country employee relationships – an aspect underexplored in the current literature. Thus, we address the following research question: What are the potential positive and negative consequences of expatriates’ boundary-spanning for the relationships between expatriates and host-country employees in MNEs? Our study contributes to the boundary-spanning literature in the IB field by offering a novel, empirically validated theoretical framework of expatriates’ boundary-spanning, which provides a more realistic, balanced, and accurate perspective. It also explains three distinct dimensions of expatriates’ boundary-spanning – functional, linguistic, and cultural – in producing both positive and negative relational outcomes. Our framework also offers practical implications for MNEs and globally mobile employees.

Theory and hypotheses

Expatriates’ boundary-spanning

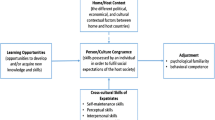

In our review of the literature, we identified three dimensions of expatriates’ boundary-spanning. Functional boundary-spanning utilizes expatriates’ domain-specific knowledge and expertise to transfer core competencies between units, narrow knowledge gaps, and standardize management practices (Harzing et al., 2016). Linguistic boundary-spanning aims to address language-related issues beyond functional realms (Harzing & Pudelko, 2014). It involves more than literal translation as language serves as an important means of transmitting tacit and explicit knowledge (Welch & Welch, 2008). Cultural boundary-spanning refers to activities that exploit expatriates’ cross-cultural knowledge and understanding to navigate cultural differences and establish connections (Backmann et al., 2020). In what follows, we theorize on how these dimensions of expatriates’ boundary-spanning collectively influence the relational outcomes between expatriates and host-country employees and how each dimension contributes to such mechanisms. Our theoretical framework is depicted in Fig. 1.

The double-edged effects of expatriates’ boundary-spanning

Social capital theory proposes that individuals can derive mutual benefits from their relationships with others (Kostova & Roth, 2003). Social capital is represented by social interaction, trust, and shared visions and goals between individuals (Reiche et al., 2009; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Through boundary-spanning, expatriates and host-country employees collaborate closely, forming interpersonal ties that are the foundation of social capital (Shimoda, 2013). Such collaboration and connection allow each party to interact and gain what they need from the respective working relationship, thus fostering reliance on each other. Reciprocity also plays a significant role in shaping these exchange relationships (Molm et al., 2007). In turn, this task-related and informal interdependence and reciprocity contribute to the development of mutual trust. Mutual trust is characterized by two parties displaying complementary levels of vulnerability in a shared context based on positive expectations of each other’s intentions and behaviors (Korsgaard et al., 2015). This kind of trust is a crucial aspect in the interpersonal relationships between expatriates and host-country employees (Shimoda, 2013).

Expatriates’ boundary-spanning and the resulting formation of mutual trust help disseminate the shared values and collective goals of organizations (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998), particularly those with which these individuals may have had prior limited familiarity (e.g., subsidiaries for expatriates and MNEs for host-country employees). In turn, both expatriates and host-country employees gain a deeper understanding of and stronger affective connection with their counterpart organizations (Schaubroeck et al., 2013), thereby cultivating a stronger sense of organizational identification (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). As a result, expatriates can feel a sense of belonging to subsidiaries, and host-country employees perceive a closer connection with MNEs. Altogether, through the development of mutual trust, expatriates’ boundary-spanning enhances the mutual identification pattern for both expatriates and host-country employees, strengthening their sense of belonging to or identification with their counterpart organizations (Rousseau, 1998).

Hypothesis 1

Expatriates’ boundary-spanning facilitates the development of mutual trust between expatriates and host-country employees, which in turn promotes (a) expatriates’ subsidiary identification and (b) host-country employees’ MNE identification.

Role theory suggests that the varied expectations embedded within their roles can create stress for individuals (Kahn et al., 1964). Therefore, when working under implicit pressure and juggling multiple roles, including their official jobs and on-demand boundary-spanning activities, expatriates often experience work-related stressors, such as role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload (Au & Fukuda, 2002; Stamper & Johlke, 2003). These role stressors exacerbate adverse effects for expatriates and can potentially lead to emotional exhaustion (Zhao & Jiang, 2022), which is characterized by the feeling of being overextended and depleted of psychological and physical resources (Maslach et al., 2001). Specifically, the challenge of managing multiple unclearly defined roles frequently exposes expatriates to overwhelming stressors, making them susceptible to emotional exhaustion (Bhanugopan & Fish, 2006).

Furthermore, high levels of role stressors may leave expatriates with limited physical, emotional, and cognitive resources to handle their workload (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In response, expatriates may activate self-regulatory mechanisms to alleviate stress (Repetti, 1992). These mechanisms involve surface-level social integration (Fan et al., 2023) whereby expatriates limit their interactions with host-country employees to only necessary boundary-spanning activities while refraining from using their already-scarce resources to conduct extra activities or adjusting their attitudes and behaviors to socialize with host-country employees. This diminished adaption and socialization may lead host-country employees to view expatriates as dissimilar to themselves in terms of values, attitudes, and behaviors. Consequently, host-country employees may perceive stressed expatriates as not belonging to their ingroup, thereby categorizing them as outgroup members (Toh & DeNisi, 2007).

Hypothesis 2

Expatriates’ boundary-spanning increases their role stressors, which in turn (a) exacerbates their emotional exhaustion and (b) increases their chances of being categorized as outgroup members by host-country employees.

The effects of the subdimensions of expatriates’ boundary-spanning

Each dimension of expatriates’ boundary-spanning has a distinct primary knowledge base (Barner-Rasmussen et al., 2014) and composition of explicit and tacit elements (Li & Scullion, 2010). Accordingly, we refine the double-edged framework by examining the role of each dimension separately. In theorizing their effects on mutual trust, we differentiate two forms of trust discussed in the literature: cognition-based trust, which is based on the rational evaluation of a person’s reliability, dependability, and competency, and affect-based trust, which builds on emotional bonds (McAllister, 1995).

First, functional boundary-spanning mainly deals with the domain-specific capabilities and firm-specific behavioral standards that expatriates bring to foreign subsidiaries (Harzing et al., 2016; Takeuchi et al., 2019). Dealing with these types of explicit knowledge demonstrates expatriates’ abilities and behavioral integrity, which likely increases host-country employees’ cognition-based trust in them (Tomlinson et al., 2020). Additionally, host-country employees likely reciprocate expatriates’ boundary-spanning efforts by providing information to assist them in functioning and problem-solving in the host country (Farh et al., 2010) and in delivering expected work outcomes (Ang & Tan, 2016). Such reciprocal actions demonstrate host-country employees’ abilities and behavioral integrity, likely fostering expatriates’ cognition-based trust in them.

Next, cultural boundary-spanning requires individuals to accommodate different values, beliefs, and norms (Johnson et al., 2006), thereby transferring more tacit knowledge, which is difficult to formalize and is practice and context-specific (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2001). In this process, the use of cultural knowledge and metacognition influences the development of affect-based trust (Chua et al., 2012). Namely, when expatriates use their knowledge to interpret situations and interactions unique to different cultural contexts, their adept behavior helps prevent misunderstanding and potential tensions that may otherwise hinder the formation of affect-based interpersonal relationships. In this process, host-country employees also tend to extend empathetic emotional support to expatriates experiencing adjustment difficulties (Farh et al., 2010). Such reciprocal behavior fosters host-country employees’ affect-based trust in expatriates and vice versa.

Compared with functional and cultural boundary-spanning, the relationships between linguistic boundary-spanning and affect- and cognition-based mutual trust are both likely moderate. Research suggests that limited shared language proficiency in multinational teams may reduce members’ perceived task competence and dependability, which may diminish their perceived ability- and integrity-based trust. This situation can also evoke language-based anxiety among team members with lower language proficiency that reduces their emotion-based intentions to trust by not showing their vulnerabilities to people with higher language proficiency (Tenzer et al., 2014). Thus, expatriates who perform linguistic boundary-spanning likely facilitate shared language proficiency with host-country employees and, accordingly, develop cognition-based and affect-based mutual trust. However, even with a shared language, language barriers may persist in the form of pragmatic and prosodic differences (Tenzer et al., 2021). Thus, although linguistic boundary-spanning may resolve some visible language barriers and enhance mutual trust, hidden language barriers may still trigger negative cognitive and affective responses in others.

Hypothesis 3

(a) Functional boundary-spanning is more strongly related to cognition-based mutual trust and (b) cultural boundary-spanning is more strongly related to affect-based mutual trust than the other dimensions of boundary-spanning.

Performing functional boundary-spanning tends to be seen as within the realm of expatriates’ formal responsibilities, which reinforces high demands and expectations from host-country employees. These heightened demands and expectations may lead to additional workload and role stressors for expatriates. The complex work demands from different parties can trigger expatriates’ role ambiguity and role conflict, especially when they receive insufficient support from host-country employees, causing a significant burden to fall on expatriates’ shoulders. On the other hand, despite the mental challenges of working with foreign languages (Volk et al., 2014) and the cognitive effort required to interact with diverse cultures (Rozkwitalska, 2017), expatriates can often mitigate role stressors stemming from linguistic and cultural boundary-spanning for two key reasons. First, both expatriates and host-country employees play a role in enhancing mutual linguistic and cultural understanding. While expatriates often make efforts to learn local languages and cultures (Zhang & Harzing, 2016), host-country employees also contribute to fostering mutual understanding by acting as cultural interpreters and communication facilitators (Vance et al., 2009). Second, given that expatriates’ positions connect headquarters and subsidiaries, they may anticipate and internalize expectations related to bridging linguistic and cultural gaps (Wiener, 1982). As a result, expatriates often demonstrate relatively high efficiency in coping with role stressors associated with linguistic and cultural boundary-spanning.

Hypothesis 4

Functional boundary-spanning is more strongly related to role stressors than the other dimensions of boundary-spanning.

Methods

Data and participants

We collected three datasets in 2022, the first two of which were used to develop a scale to measure expatriates’ boundary-spanning. Dataset 1 was collected through a Japanese online research panel for exploratory factor analysis (EFA). It included 355 participants (57% male, Mage = 39.04) who were Japanese expatriates within the last 3 years. Dataset 2 was collected through a Chinese online research panel for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and included 660 employees (330 Chinese expatriates and 330 host-country coworkers, 50.94% female, Mage = 36.92) who worked in a Chinese MNE within the last 3 years. Dataset 3 was the main dataset and was collected through author connections in the energy engineering industry of Chinese MNEs based in Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia. We chose this industry due to the significant deployment of expatriates resulting from the “Belt and Road Initiative,” providing us access to paired data for expatriates and host-country employees. We collected dyadic data (64% overall response rate) from a total of 177 expatriate–host-country coworker pairs in two waves with a 2-week interval using paper-based questionnaires or online surveys (expatriates: Mage = 33.91, 50.28% female, Msubsidiary tenure = 2.63; host-country coworkers: Mage = 31.84, 51.98% female, Msubsidiary tenure = 3.37).

Measures

All measures (see the online appendix for the full scales) other than the control variables were assessed using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). To ensure scale validity and verb accuracy, we conducted a back-translation process (Brislin, 1980).

Independent variable

We developed a new scale for expatriates’ boundary-spanning following Hinkin’s (1998) scale-development procedure. From 70 initial items generated through interviews and the literature, we retained 29 items after assessing clarity and content validity. EFA and CFA on two separate datasets validated the measure. The EFA with Oblimin rotation on Dataset 1 (n = 355) supported a three-factor solution. After eliminating three items with cross-loadings, our final 26-item scale includes nine items for functional, seven items for linguistic, and ten items for cultural boundary-spanning (see the appendix). Next, the CFA results from Dataset 2 (n = 660) supported the proposed three-dimensional structure of this scale, χ2[296] = 1077.60, p < 0.01; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.94; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.94; standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR) = 0.03; root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06. Similar results were obtained from the 177 dyads from Dataset 3 (reported by host-country coworkers; χ2[296] = 409.17, p < 0.01; TLI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.04; RMSEA = 0.05). The EFA and CFA demonstrated consistent results among the three reflective indicators, allowing us to compute expatriates’ boundary-spanning as a multidimensional construct comprising functional, linguistic, and cultural dimensions. In line with previous research [e.g., Connelly et al. (2019)], we utilized expatriates’ boundary-spanning as the entire measure when we tested the hypotheses in which the overall boundary-spanning construct was of interest, whereas to test the hypotheses dealing with the specific types of boundary-spanning separately, we employed each indicator as a separate measure.

Mediating variables

Mutual trust, cognition-based mutual trust, and affect-based mutual trust were reported by both expatriates and host-country coworkers (11 items; McAllister, 1995). We found a high level of agreement in trust between host-country employees and expatriates: interrater agreement (rwg[j]) (James et al., 1984) showed rwg[j] values of 0.86 for mutual trust, 0.80 for cognition-based mutual trust, and 0.67 for affect-based mutual trust. Thus, we computed the measures for mutual trust, cognition-based mutual trust, and affect-based mutual trust based on the indicator of the square root of the product (SRP) (Smith & Barclay, 1997) because the SRP includes both level and agreement facets:

Role stressors were indicated by expatriates (17 items; Rizzo et al., 1970; Beehr et al., 1976).

Dependent variables

Subsidiary identification (reported by expatriates) and MNE identification (reported by host-country coworkers) were both measured using an organizational identification scale (six items; Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Emotional exhaustion was reported by expatriates (nine items; Maslach & Jackson, 1981), and outgroup categorization was reported by host-country coworkers (seven items; Leonardelli & Toh, 2011).

Control variables

We included expatriates’ and host-country coworkers’ age, gender, industry, tenure in their subsidiaries, and foreign language proficiency (Liu & Jackson, 2008).

Results

Preliminary results

We first examined the variance inflation factors (VIFs) to test for multicollinearity issues. The VIFs ranged from 1.06 to 2.38, falling far below the accepted cutoff value of 10 (Myers, 1990) and thereby indicating no multicollinearity. To mitigate potential common method variance (CMV), we followed the suggestions of Podsakoff et al. (2003) and collected measures from different sources and at different time points in the research-design stage. Furthermore, we conducted a Harman’s single-factor test and found that the variance explained by the first factor was 25.58%, falling short of accounting for half of the total variance. We also performed unmeasured latent common factor analysis. Despite a significant chi-square difference (Δχ2 = 271.23, Δdf = 39, p < 0.05) before and after including the method factor, the hypothesized factors explained 56.92% of the total variance, whereas the method factor explained 17.98%. These findings led us to conclude that CMV did not play a major role in our analysis.

We also conducted higher-order CFA to validate our higher-order model with ten first-order factors and two second-order factors. Expatriates’ boundary-spanning and mutual trust were second-order factors, while the remaining factors were considered first-order factors. Since the original measures consisted of many indicators with a limited sample size, we reduced the number of indicators for each latent variable using item parceling [e.g., Sekiguchi et al. (2017)]. The results indicated that the hypothesized model fit the data well (χ2[676] =1166.90, p < 0.01; TLI = 0.92; CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.08; RMSEA = 0.06). The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Hypothesis testing

To test Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b, we conducted bootstrapping-based mediation tests using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) with 5000 resamples to produce 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the estimated indirect effects. Tables 2 and 3 report the regression results for the positive and negative paths in our model. According to the mediation results, expatriates’ boundary-spanning was associated with expatriates’ subsidiary identification (indirect effect = 0.20, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.07, 0.36]) and host-country coworkers’ MNE identification (indirect effect = 0.22, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.08, 0.40]), both of which were mediated by mutual trust. Thus, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. Expatriates’ boundary-spanning was also associated with emotional exhaustion (indirect effect = 0.41, SE = 0.09, 95% CI [0.25, 0.60]) and outgroup categorization (indirect effect = 0.26, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.12, 0.43]), both of which were mediated by role stressors. Therefore, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

To test Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 4, we performed relative weight analysis to examine the relative importance of each type of boundary-spanning on cognition-based and affect-based mutual trust and role stressors (Tonidandel & LeBreton, 2011). The results are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2 and provide support for Hypothesis 3b and 4. Hypothesis 3a was not supported because cultural boundary-spanning had the strongest relationship with cognition-based mutual trust followed by functional and linguistic boundary-spanning. In summary, all our hypotheses except Hypothesis 3a were fully supported.

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical contributions

The main theoretical contribution of this study is that we develop a comprehensive framework of the double-edged phenomenon of expatriates’ boundary-spanning that incorporates two theoretical lenses – namely, social capital theory and role theory. Through a social capital theory lens, we identify several positive relational outcomes of expatriates’ boundary-spanning. Specifically, it benefits organizations by increasing mutual trust between expatriates and host-country employees, which further leads to a mutual organizational identification pattern. On the other hand, through a role theory lens, our study reveals the potential dark side of expatriates’ boundary-spanning, which can result in negative emotional outcomes and outgroup categorization due to expatriates’ conflicting roles. By combining these two theoretical lenses, our framework sheds light on both the positive and negative relational outcomes of expatriates’ boundary-spanning, providing a more accurate and realistic understanding of this phenomenon in the IB field.

Our study further contributes to the theoretical understanding of how different types of expatriates’ boundary-spanning – namely, functional, linguistic, and cultural – contribute to double-edged relational outcomes. First, our findings suggest that functional boundary-spanning primarily fosters cognition-based mutual trust mainly through the exchange of explicit knowledge (Harzing et al., 2016; Takeuchi et al., 2019), whereas cultural boundary-spanning promotes not only affect-based mutual trust but also cognition-based mutual trust. These findings might reflect how engaging in cultural boundary-spanning helps transform context-specific and hands-on knowledge (i.e., tacit knowledge) into clear and comprehensible information (i.e., explicit knowledge) during cross-cultural knowledge transfer. Thus, while cultural boundary-spanning develops affect-based mutual trust through tacit knowledge-sharing, it also promotes cognition-based mutual trust through explicit knowledge-sharing, making it the most influential in developing social capital. In contrast to functional and cultural boundary-spanning, linguistic boundary-spanning does not have a strong direct influence on mutual trust. Rather, it might be a necessary condition for other types of boundary-spanning to operate effectively (Backmann et al., 2020; Barner-Rasmussen et al., 2014). Indeed, language is deeply embedded in the IB context, and overcoming language barriers is crucial for functional and cultural boundary-spanning to promote mutual trust (Tenzer et al., 2014).

Second, our findings show that all three types of boundary-spanning cause role stressors and subsequent negative relational outcomes, which are potential costs in cultivating social capital and achieving positive outcomes. In particular, functional and cultural boundary-spanning require greater effort from expatriates to understand and exchange knowledge with host-country employees, resulting in relatively strong role stressors. In contrast, linguistic boundary-spanning requires less effort as language processing becomes more automatic as one’s foreign language proficiency increases (Volk et al., 2014). Similar to the case of developing social capital, linguistic boundary-spanning can be an essential medium in facilitating other types of boundary-spanning (Barner-Rasmussen et al., 2014). Altogether, our findings suggest that cultural boundary-spanning has the strongest double-edged effects; linguistic boundary-spanning shows the weakest effects; and functional boundary-spanning presents asymmetric effects, with negative outcomes possibly exceeding positive outcomes.

Practical implications

Our study also has practical implications for MNEs and managers. First, MNEs should implement policies that amplify the positive effects of expatriates’ boundary-spanning while mitigating the negative ones. To maximize the positive effects, global managers should assess expatriates’ functional, linguistic, and cultural knowledge to ensure they possess the necessary skills and offer training if necessary to meet the demands and expectations of host-country employees. To minimize the negative effects, global managers should clarify job responsibilities to help expatriates anticipate and cope with challenges and be attentive to expatriates’ well-being by providing more organizational support and encouraging assistance from host-country employees.

Second, our implications extend to other globally mobile employees, such as self-initiated expatriates and third-country nationals engaged in boundary-spanning within MNEs’ global operations (Barmeyer et al., 2020; Furusawa & Brewster, 2019). They should be aware of both the positive and potential detrimental impacts of boundary-spanning. As more people engage in cross-border work, our findings can guide them in effectively navigating boundary-spanning in multinational operations.

Limitations and future research directions

First, our main dataset might have been vulnerable to selection bias due to our use of paired data from only one coworker per expatriate and our adoption of the singular energy engineering industry comprising only Chinese MNEs. Additionally, considering that our main dataset was collected in 2022, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, host-country employees’ responses to Chinese expatriates may have been influenced. Thus, future studies could collect dyadic data from multiple coworkers per expatriate and broaden the sample by including data from other industries, time periods, and countries. Second, despite the use of multisource data, our study design has limitations related to causal inference. Future studies could adopt a longitudinal design and examine the development of expatriate–host-country employee relationships over time. Such an approach could constructively replicate and extend the results we obtained. Third, we only measured the organizational identification of expatriates with subsidiaries and of host-country employees with MNEs. Future studies could measure dual organizational identification (Ishii, 2012; Vora & Kostova, 2007) and explore the dynamic relationship between the two foci of organizational identification.

Future research could also refine or extend our theoretical framework by examining different aspects of social capital theory and role theory. For example, when applying social capital theory, one promising research avenue is exploring how culture influences the dynamics of mutual trust between expatriates and host-country employees. This research is relevant given that various cultures foster different types of trust (Chua et al., 2012), and it is significant to understand how inter-cultural trust evolves in hierarchical relationships (Bueechl et al., 2023). Such an investigation could add nuanced insights into the double-edged effects of boundary-spanning. When applying role theory, it would be beneficial to explore other potential consequences of role stressors like counterproductive behavior (Belschak & Den Hartog, 2009). Additionally, future research could explore possible positive outcomes (Au & Fukuda, 2002), such as role consensus (Anglin et al, 2022) and role novelty (Kawai & Mohr, 2015). In conclusion, the double-edged framework we proposed and empirically validated in this study simultaneously highlights both the bright and dark sides of expatriates’ boundary-spanning and opens new avenues for research on globally mobile individuals and the impact of their boundary-spanning activities in the MNE context.

References

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2001). Tacit knowledge: Some suggestions for operationalization. Journal of Management Studies, 38(6), 811–829.

Ang, F., & Tan, H. H. (2016). Trust building with Chinese host country nationals. Journal of Global Mobility, 4(1), 44–67.

Anglin, A. H., Kincaid, P. A., Short, J. C., & Allen, D. G. (2022). Role theory perspectives: Past, present, and future applications of role theories in management research. Journal of Management, 48(6), 1469–1502.

Au, K. Y., & Fukuda, J. (2002). Boundary spanning behaviors of expatriates. Journal of World Business, 37(4), 285–296.

Backmann, J., Kanitz, R., Tian, A. W., Hoffmann, P., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Cultural gap bridging in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(8), 1283–1311.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.

Barmeyer, C., Stein, V., & Eberhardt, J. M. (2020). Third-country nationals as intercultural boundary spanners in multinational corporations. Multinational Business Review, 28(4), 521–547.

Barner-Rasmussen, W., Ehrnrooth, M., Koveshnikov, A., & Mäkelä, K. (2014). Cultural and language skills as resources for boundary spanning within the MNC. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(7), 886–905.

Beehr, T. A., Walsh, J. T., & Taber, T. D. (1976). Relationships of stress to individually and organizationally valued states: Higher order needs as a moderator. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(1), 41–47.

Belschak, F. D., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2009). Consequences of positive and negative feedback: The impact on emotions and extra-role behaviors. Applied Psychology, 58(2), 274–303.

Bhanugopan, R., & Fish, A. (2006). An empirical investigation of job burnout among expatriates. Personnel Review, 35(4), 449–468.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Bueechl, J., Pudelko, M., & Gillespie, N. (2023). Do Chinese subordinates trust their German supervisors? A model of inter-cultural trust development. Journal of International Business Studies, 54, 768–796.

Chua, R. Y., Morris, M. W., & Mor, S. (2012). Collaborating across cultures: Cultural metacognition and affect-based trust in creative collaboration. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 118(2), 116–131.

Connelly, C. E., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 779–782.

Fan, S. X., Zhu, F., & Shaffer, M. A. (2023). Missed connections: A resource-management theory to combat loneliness experienced by globally mobile employees. Journal of International Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00658-3

Farh, C. I., Bartol, K. M., Shapiro, D. L., & Shin, J. (2010). Networking abroad: A process model of how expatriates form support ties to facilitate adjustment. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 434–454.

Furusawa, M., & Brewster, C. (2019). The determinants of the boundary-spanning functions of Japanese self-initiated expatriates in Japanese subsidiaries in China: Individual skills and human resource management. Journal of International Management, 25(4), 100674.

Harzing, A. W., & Pudelko, M. (2014). Hablas vielleicht un peu la mia language? A comprehensive overview of the role of language differences in headquarters–subsidiary communication. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(5), 696–717.

Harzing, A. W., Pudelko, M., & Reiche, B. S. (2016). The bridging role of expatriates and inpatriates in knowledge transfer in multinational corporations. Human Resource Management, 55(4), 679–695.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1, 104–121.

Hsu, Y. S., Chen, Y. P., Chiang, F. F., & Shaffer, M. A. (2022). It takes two to tango: Knowledge transfer between expatriates and host country nationals. Human Resource Management, 61(2), 215–238.

Ishii, K. (2012). Dual organizational identification among Japanese expatriates: The role of communication in cultivating subsidiary identification and outcomes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(6), 1113–1128.

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 85–89.

Johnson, J. P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 525–543.

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Conflict and ambiguity: Studies in organizational roles and individual stress. International Journal of Stress Management, 1, 309–322.

Kawai, N., & Mohr, A. (2015). The contingent effects of role ambiguity and role novelty on expatriates’ work-related outcomes. British Journal of Management, 26(2), 163–181.

Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2015). It isn’t always mutual: A critical review of dyadic trust. Journal of Management, 41(1), 47–70.

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2003). Social capital in multinational corporations and a micro-macro model of its formation. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 297–317.

Leonardelli, G. J., & Toh, S. M. (2011). Perceiving expatriate coworkers as foreigners encourages aid. Psychological Science, 22(1), 110–117.

Li, S., & Scullion, H. (2010). Developing the local competence of expatriate managers for emerging markets: A knowledge-based approach. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 190–196.

Liu, M., & Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 71–86.

Liu, X., & Shaffer, M. A. (2005). An investigation of expatriate adjustment and performance: A social capital perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 5(3), 235–254.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

Mäkelä, K. (2007). Knowledge sharing through expatriate relationships: A social capital perspective. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(3), 108–125.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

Meyer, K. E., Li, C., & Schotter, A. P. (2020). Managing the MNE subsidiary: Advancing a multi-level and dynamic research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, 538–576.

Molm, L. D., Schaefer, D. R., & Collett, J. L. (2007). The value of reciprocity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(2), 199–217.

Myers, R. H. (1990). Classical and modern regression with applications (Vol. 2). Duxbury Press.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Reiche, B. S., Harzing, A. W., & Kraimer, M. L. (2009). The role of international assignees’ social capital in creating inter-unit intellectual capital: A cross-level model. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(3), 509–526.

Repetti, R. L. (1992). Social withdrawal as a short-term coping response to daily stressors. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Hostility, coping, and health (pp. 151–165). American Psychological Association.

Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., & Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15(2), 150–163.

Rousseau, D. M. (1998). Why workers still identify with organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 217–233.

Rozkwitalska, M. (2017). Cognition of the multicultural work environment in multinational corporations and intercultural interaction outcomes. In M. Rozkwitalska, Ł Sułkowski, & S. Magala (Eds.), Intercultural interactions in the multicultural workplace (pp. 37–51). Springer.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C., & Hannah, S. T. (2013). Developing trust with peers and leaders: Impacts on organizational identification and performance during entry. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1148–1168.

Schotter, A. P., Mudambi, R., Doz, Y. L., & Gaur, A. (2017). Boundary spanning in global organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 54(4), 403–421.

Sekiguchi, T., Li, J., & Hosomi, M. (2017). Predicting job crafting from the socially embedded perspective: The interactive effect of job autonomy, social skill, and employee status. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(4), 470–497.

Shimoda, Y. (2013). Talk, trust and information flow: Work relationships between Japanese expatriate and host national employees in Indonesia. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(20), 3853–3871.

Smith, J. B., & Barclay, D. W. (1997). The effects of organizational differences and trust on the effectiveness of selling partner relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 3–21.

Stamper, C. L., & Johlke, M. C. (2003). The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between boundary spanner role stress and work outcomes. Journal of Management, 29(4), 569–588.

Takeuchi, R., Li, Y., & Wang, M. (2019). Expatriates’ performance profiles: Examining the effects of work experiences on the longitudinal change patterns. Journal of Management, 45(2), 451–475.

Tenzer, H., Pudelko, M., & Harzing, A. W. (2014). The impact of language barriers on trust formation in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5), 508–535.

Tenzer, H., Pudelko, M., & Zellmer-Bruhn, M. (2021). The impact of language barriers on knowledge processing in multinational teams. Journal of World Business, 56(2), 101184.

Toh, S. M., & DeNisi, A. S. (2007). Host country nationals as socializing agents: A social identity approach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(3), 281–301.

Tomlinson, E. C., Schnackenberg, A. K., Dawley, D., & Ash, S. R. (2020). Revisiting the trustworthiness–trust relationship: Exploring the differential predictors of cognition-and affect-based trust. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 535–550.

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: A useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26, 1–9.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464–476.

Vance, C. M., Vaiman, V., & Andersen, T. (2009). The vital liaison role of host country nationals in MNC knowledge management. Human Resource Management, 48(4), 649–659.

Volk, S., Köhler, T., & Pudelko, M. (2014). Brain drain: The cognitive neuroscience of foreign language processing in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 45, 862–885.

Vora, D., & Kostova, T. (2007). A model of dual organizational identification in the context of the multinational. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(3), 327–350.

Wang, G., Liu, X., & Liu, Y. (2019). Role overload, knowledge acquisition and job satisfaction: An ambidexterity perspective on boundary-spanning activities of IT employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(4), 728–757.

Welch, D. E., & Welch, L. S. (2008). The importance of language in international knowledge transfer. Management International Review, 48, 339–360.

Wiener, Y. (1982). Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Academy of Management Review, 7(3), 418–428.

Yang, J. Y., Wen, L., Volk, S., & Lu, J. W. (2022). Temporal boundaries and expatriate staffing: Effects of parent–subsidiary work-time overlap. Journal of World Business, 57(6), 101367.

Zhang, L. E., & Harzing, A. W. (2016). From dilemmatic struggle to legitimized indifference: Expatriates’ host country language learning and its impact on the expatriate-HCE relationship. Journal of World Business, 51(5), 774–786.

Zhao, H., & Jiang, J. (2022). Role stress, emotional exhaustion, and knowledge hiding: The joint moderating effects of network centrality and structural holes. Current Psychology, 41, 8829–8841.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the guidance and insightful comments provided by Special Issue Editor Stacey Fitzsimmons, Editor-in-Chief Rosalie L. Tung, and the three anonymous reviewers. We also thank Allan Bird, Azusa Ebisuya, and Jie Li for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of our manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP20K13589 and JP20H01530, and NSFC Grant Number 72272049.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Stacey Fitzsimmons, Guest Editor, 25 January 2024. This article has been with the authors for five revisions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: The subdimensions of and scale for expatriates’ boundary-spanning

Appendix: The subdimensions of and scale for expatriates’ boundary-spanning

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Sekiguchi, T., Qin, J. et al. Expatriates’ boundary-spanning: double-edged effects in multinational enterprises. J Int Bus Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-024-00690-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-024-00690-x