Abstract

In this paper, I shall assess the ontological commitments of frame-based methods of knowledge representation. Frames decompose concepts (statements, theories) into recursive attribute-value structures. The question is: are the attribute values in frames to be interpreted as universal properties or rather as tropes? I shall argue that universals realism and trope theory face similar complications as far as non-terminal values, i.e., values which refer to the determinable properties of objects, are concerned. It is suggested that these complications can be overcome if one is prepared to adopt an ontology of structured complexes. Such an ontology, in turn, is indifferent as to whether attribute values are interpreted as universals or as tropes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

02 April 2018

In Hommen (2017), I refer to the work of Garcia in Garcia (2015a, b). In this addendum, I would like to supplement additional references to these papers.

02 April 2018

In Hommen (2017), I refer to the work of Garcia in Garcia (2015a, b). In this addendum, I would like to supplement additional references to these papers.

02 April 2018

In Hommen (2017), I refer to the work of Garcia in Garcia (2015a, b). In this addendum, I would like to supplement additional references to these papers.

Notes

This section builds on material originally presented in Hommen and Osswald (2016, pp. 97–99).

There is a further distinction between universals which, however, will not play a role in the following investigation: that between transcendent or Platonic universals and immanent or Aristotelian universals. Transcendent universals are taken to be abstract (i.e., non-spatiotemporal) entities that might exist even if no concrete particular ever instantiates them. Immanent universals, by contrast, are ‘wholly existent’ (and identical) in all their concrete instances; thus, there cannot be uninstantiated Aristotelian universals.

Again, this does not guarantee that what we commit ourselves to really exists. After all, the statements or theories we accept might be false. The ontological commitments of our accepted statements or theories merely tell us what would exist if these statements or theories were true.

I treat them in more detail in a forthcoming paper.

The distinction that I wish to draw the attention to has also been suggested, under a different label, by Loux (2015, p. 31) who speaks of ‘tropes’ (in the modifier sense) and ‘tropers’ (i.e., module tropes).

However, some module trope theorists would even deny this. Instead, they would insist that module tropes, though they are character grounders in their view, are not properties, for properties are logical constructions out of module tropes, i.e., resemblance classes of module tropes. These module trope theorists would classify their ontological position as a form of property nominalism rather than property realism.

According to Garcia, the object/property distinction, as it is laid out here, also does not coincide with the distinction between independent and dependent entities. As he says, “both independent modifier tropes (transferable or even free-floating modifier tropes) and dependent (non-transferable) module tropes are conceivable” (cf. Garcia 2015b, p. 638).

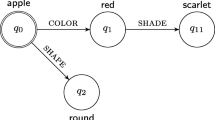

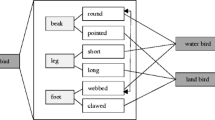

We may get another grasp of the general difficulty that emerges if we remind ourselves of the fact that frames decompose the concepts they represent: the idea is that the attributes in a frame retrieve information implicitly contained in the types of their arguments. Thus, applying the attribute color to an entity of the type Tweety yields the information that Tweety is yellow, because, as the type signature specifies, the predicate ‘being yellow’ is already part of the complex predicate ‘being Tweety.’ Yet, applying the attribute shade to an entity of the type yellow does not yield any information about the determinate shade of yellow exemplified by this entity, because the predicate ‘being yellow’—no matter whether it is analyzed as rigidly designating a determinable property or as non-rigidly designating members in a class of determinate properties—carries no implication as to which determinate predicate (‘being citrine,’ ‘being saffron’ or whatever) applies to its referent(s).

The modifier trope theorist will, of course, have to say more about how ‘natural resemblance classes’ of tropes are defined. So much is clear: as a result of such a definition, all the fs should fall in a class that is grouped together by a certain determinate predicate, while all the gs should fall in a class that is grouped together by a certain determinable predicate.

Colocation seems neither necessary nor sufficient for coinherence. On the one hand, there might be extended simples—objects which have no parts but a size greater than zero—that have, e.g., a trope f on one half and a trope g on the other, where \(f\ne g\). On the other hand, there might be interpenetrating objects—objects which are distinct yet colocated—that have colocated tropes which are not coinherent. Cf. Giberman (2014, p. 462).

Disputes typically concern whether the postulation of compresence tropes gives rise to a vicious regress: for trope f to be compresent with trope g, they must be linked by a compresence trope c. But for f and g to be linked by c, it seems that c must be compresent with f and g by way of further compresence tropes, \(c'\) and \(c''\), and so on. Cf. Campbell et al. (2015).

The trope-theoretic frame theorist could choose to let the value yellow refer, not to the determinable yellowness trope but, to the relevantly unique compresence trope that fixes the coexemplification of that determinable and its unique determinate. For reasons of parity, however, the universals realist would have to be allowed to shift the reference of the value yellow as well—namely, from the universal yellowness to (what I will call) the ‘structured complex’ involving both Tweety and yellowness, in which case the determinate shade of Tweety’s color would be equally fixed. This anticipates my solution to the problem of recursive specification (cf. Sect. 6.2). The important point here is that equivalent solutions are available to both the trope theorist and the universals realist, and so no decisive contribution is being made to the economy of either’s ontological interpretation of frame theory.

Conveniently, such a tie would also not seem to be subject to a relation regress; cf. footnote 13.

Accordingly, Yablo’s account of token determination reads thus: “f determines g [if and] only if (i) necessarily, if f exists, then g exists and is coincident withf, and (ii) possibly, g exists and f does not exist” (Yablo 1992, p. 265; emphasis mine, variable letters changed).

What makes it the case that a frame represents a structured complex rather than the complex type that the structured complex is a token of? Well, it is its being a frame rather than a frame type. Do frames (in contrast to frame types) typically involve times and places? No; frames typically involve existential presuppositions (as is explicit in the translation in (3)). They involve times and places only to the extent that the entities whose existence they presuppose (like, for instance, Tweety) involve times and places.

The ontology of structured complexes is even impartial as to whether the properties are conceived as immanent or rather transcendent universals; cf. footnote 2.

Expressions for substances and substrata will implicitly refer to locations as well. But explicit references to locations may be preferable if one wants to take account of the fact that objects typically can change properties over times and places. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for making me aware of this point.

References

Andersen, H., Barker, P., & Chen, X. (2006). The cognitive structure of scientific revolutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Andersen, H., & Nersessian, N. (2000). Nomic concepts, frames, and conceptual change. Philosophy of Science, 67, 224–241.

Armstrong, D. (1989). Universals: An opinionated introduction. Focus Series. Boulder: Westview Press.

Armstrong, D. (1997). A world of states of affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barsalou, L. W. (1992). Frames, concepts, and conceptual fields. In A. Lehrer & E. F. Kittay (Eds.), Frames, fields and contrasts. New essays in semantic and lexical organization (pp. 21–74). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Campbell, K. (1990). Abstract particulars. Oxford: B. Blackwell.

Campbell, K., Franklin, J., & Ehring, D. (2015). Donald Cary Williams. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (summer 2015 ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/williams-dc/

Carnap, R. (1956). The methodological character of theoretical terms. In H. Feigl & M. Scriven (Eds.), Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science (pp. 38–76). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Carpenter, B. (1992). The logic of typed feature structures: With applications to unification grammars, Logic programs and constraint resolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, X., & Barker, P. (2000). Continuity through revolutions: A frame-based account of conceptual change during scientific revolutions. Philosophy of Science, 67, 208–223.

Cover, J., & O’Leary-Hawthorne, J. (1999). Substance and individuation in Leibniz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eysenck, M., & Keane, M. (1990). Cognitive psychology. A student’s handbook. East Sussex: Taylor & Francis.

Fales, E. (1990). Causation and universals. New York: Routledge.

Fine, K. (2017). Naive metaphysics. Philosophical Issues, 27(1), 98–113.

Forrest, P. (1993). Just like quarks. In J. Bacon, K. Campbell, & L. Reinhardt (Eds.), Ontology, causality, and mind: Essays in honor of D. M. Armstrong (pp. 45–65). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Funkhouser, E. (2006). The determinable–determinate relation. Noûs, 40(3), 548–569.

Funkhouser, E. (2014). The logical structure of kinds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garcia, R. K. (2015a). Is trope theory a divided house? In M. Loux & G. Galluzzo (Eds.), The problem of universals in contemporary philosophy (pp. 133–155). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garcia, R. K. (2015b). Two ways to particularize a property. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1(4), 635–652.

Giberman, D. (2014). Tropes in space. Philosophical Studies, 167(2), 453–472.

Gillet, C., & Rives, B. (2005). The non-existence of determinables: Or, a world of absolute determinates as default hypothesis. Nous, 39(3), 483–504.

Guarino, N. (1992). Concepts, attributes and arbitrary relations: Some linguistic and ontological criteria for structuring knowledge bases. Data and Knowledge Engineering, 8(3), 249–261.

Hommen, D., & Osswald, T. (2016). Knowledge structures and the nature of concepts. Concepts and categorization. Systematic and historical perspectives (pp. 95–122). Mentis: Münster.

Johnson, W. E. (1921). Logic (Vol. 1). New York: Dover.

Kornmesser, S. (2016). A frame-based approach for theoretical concepts. Synthese, 193, 145–166.

Löbner, S. (2011). Concept types and determination. Journal of Semantics, 28(3), 279–333.

Loux, M. J. (2015). An exercise in constituent ontology. In G. Galluzzo & M. J. Loux (Eds.), The problem of universals in contemporary philosophy (pp. 9–45). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lowe, E. (2006). The four-category ontology: A metaphysical foundation for natural science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Markosian, N. (2014). A spatial approach to mereology. In S. Kleinschmidt (Ed.), Mereology and location (pp. 69–90). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin, C. (1980). Substance substantiated. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 58, 3–10.

Maurin, A. S. (2010). Trope theory and the bradley regress. Synthese, 175, 311–326.

Minsky, M. (1974). A framework for representing knowledge. In P. Winston (Ed.), The psychology of computer vision (pp. 211–277). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Moltmann, F. (2017). Natural language ontology. In M. Aronoff (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. http://linguistics.oxforde.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-300.

Petersen, W. (2007). Representation of concepts as frames. In J. Skilters, F. Toccafondi, & G. Stemberger (Eds.), Complex cognition and qualitative science (pp. 151–170). Riga: University of Latvia.

Petersen, W., & Werning, M. (2007). Conceptual fingerprints: Lexical decomposition by means of frames—A neuro-cognitive model. In U. Priss, S. Polovina, & R. Hill (Eds.), Conceptual structures: Knowledge architectures for smart applications (pp. 415–428). Berlin and Heidelberg and New York: Springer.

Quine, W. V. (1948). On what there is. The review of metaphysics, 2(5), 21–38.

Schaffer, J. (2001). The individuation of tropes. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 79(2), 247–257.

Sider, T. (2007). Parthood. The Philosophical Review, 116(1), 51–91.

Strawson, P. (1959). Individuals. An essay in descriptive metaphysics. London: Methuen.

Thagard, P. (1990). Concepts and conceptual change. Synthese, 82, 255–274.

van Cleve, J. (1985). Three versions of the bundle theory. Philosophical Studies, 47, 95–107.

Votsis, I., & Schurz, G. (2014). Reconstructing scientific theory change by means of frames. Concept types and frames. Application in language, cognition, and science (pp. 93–110). New York: Springer.

Wieland, J. W., & Betti, A. (2008). Relata-specific relations: A response to Vallicella. Dialectica, 62(4), 509.

Williams, D. C. (1953). The elements of being: I. Review of Metaphysics, 7(2), 3–18.

Wilson J (2008) Trope determination and contingent characterization, unpublished manuscript.

Yablo, S. (1992). Mental causation. The Philosophical Review, 101(2), 245–280.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). For comments and criticisms I am grateful to members of the Collaborative Research Centre 991 “The Structure of Representations in Language, Cognition, and Science,” as well as two anonymous reviewers of Synthese.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hommen, D. Ontological commitments of frame-based knowledge representations. Synthese 196, 4155–4183 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1649-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1649-8