Abstract

Fictional truth, or truth in fiction/pretense, has been the object of extended scrutiny among philosophers and logicians in recent decades. Comparatively little attention, however, has been paid to its inferential relationships with time and with certain deliberate and contingent human activities, namely, the creation of fictional works. The aim of the paper is to contribute to filling the gap. Toward this goal, a formal framework is outlined that is consistent with a variety of conceptions of fictional truth and based upon a specific formal treatment of time and agency, that of so-called stit logics. Moreover, a complete axiomatic theory of fiction-making TFM is defined, where fiction-making is understood as the exercise of agency and choice in time over what is fictionally true. The language \(\mathcal {L}\) of TFM is an extension of the language of propositional logic, with the addition of temporal and modal operators. A distinctive feature of \(\mathcal {L}\) with respect to other modal languages is a variety of operators having to do with fictional truth, including a ‘fictionality’ operator \(M \) (to be read as “it is a fictional truth that”). Some applications of TFM are outlined, and some interesting linguistic and inferential phenomena, which are not so easily dealt with in other frameworks, are accounted for.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, e.g., Reicher (2008). For the sake of simplicity, I follow common philosophical practice in classifying discourse about fiction into different sorts of sentences, although, strictly speaking, it would be better to draw the relevant distinctions at the level of language use.

It is worth stressing that this is a clarification, not a definition of internal sentences. Moreover, internal sentences ought not to be confused with those sentences that directly occur in fictional stories.

Of course, a sentence may also be internal to a plurality of fictional settings, but let us put this case aside for simplicity.

This formulation is rough mainly because, as pointed out in note 1, to speak of internal sentences is not entirely appropriate. A more accurate formulation ought to take into the account the circumstances of use of the relevant sentences.

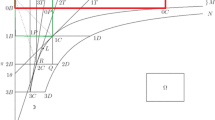

This section is only meant as a preliminary, informal presentation of these notions, which are officially introduced below, in Sect. 3.2. For those interested in the formal aspects of the proposal, it is worth anticipating that TFM is based upon Ockhamist frames, not on Branching Time frames (see below, p. 8 and Sect. 3). Thus, for instance, neither the notion of a moment nor that of a history are taken to be primitive notions, but are rather defined with reference to points and to accessibility relations between points.

This informal reading is only adequate if \(\lozenge _{\sigma }\) is not in the scope of a tense operator.

See below, Sect. 3.3. For the convenience of the reader, here is an informal characterization of the truth-conditions of sentences of \(\mathcal {L}\) involving these operators (where ‘true’ means true in an \(\mathbf{OTF}\) model):

-

(a sentence of form) \(P\mathcal {A} \,(F\mathcal {A})\) is true at \(m/h\) iff \(\mathcal {A} \) is true at some point \(m^{\prime }/h\), where \(m^{\prime }\prec m\,(m^{\prime }\succ m)\).

-

\(\lozenge \mathcal {A} \) is true at \(m/h\) iff \(\mathcal {A} \) is true at some point \(m/h'\).

-

\(\lozenge _{\sigma } \mathcal {A} \) is true at \(m/h\) iff \(\mathcal {A} \) is true at some point \(m^{\prime }/h^{\prime }\) in the same instant as \(m/h\).

-

\([\alpha _{\,k}\,{ dstit}]\mathcal {A} \) (\([{ Dstit}]\mathcal {A} \)) is true at \(m/h\) iff (a) \(\mathcal {A}\) is true at all points \(m/h^{\prime }\) such that \(h^{\prime }\) is in the same choice of \(\alpha _{k}\) (of some agent) as \(h\), and (b) \(\mathcal {A} \) is false at some point \(m/h^{\prime \prime }\).

-

Admittedly, the precise extent of this restriction is not entirely uncontroversial, for different philosophers may disagree on what fictional settings are possible in this sense. However, I would regard as possible most fictional works that are logically consistent and entail neither blatant metaphysical impossibilities nor disputable views about time, identity, the nature of things, and the like.

It might appear that Nts is at odds with certain linguistic practices. In particular, we often use present-tense metafictional sentences to report fictional works set in the past or in the future. For instance, we can say:

-

(*)

In Julius Caesar, Brutus commits suicide.

even though, in Julius Caesar, it is clearly false that Brutus’s suicide occurs now. However, these uses may be explained by assuming that, in sentences like (*), the present tense is temporally idle (‘eternal’ or ‘historical’) and so without postulating genuine temporal shifts. Whether there are ‘fictionality’ operators that are prone to induce temporal shifts is a delicate issue, which we cannot tackle here (see Predelli 2008 for a discussion; see also Voltolini 2006 and references therein on the interplay between fictional discourse and contextual shifts). Be that as it may, Nts entails that our ‘fictionality’ operators are not among them.

-

(*)

I am grateful to an anonymous referee for having brought this problem to my attention.

Recall that here trees are taken to extend indefinitely toward both the past and a future (see above, p. 5), a feature that makes them at least questionable as representations of the physical universe.

\(\mathbf{TFM}^{-} \) and \(\mathbf{OTF}^{-}\) frames are formally characterized below, in note 19.

Walton (1990, p. 87) countenances the possibility that a story comes into existence as a result of purely natural, non-agentive processes; Currie (2010, § 1.4) disagrees. Anyway, we may easily imagine a mischievous author that, in order to falsify Creation, adopts a peculiar, ‘random’ method of composition that prevents the resulting work from being counted as a deliberate creation.

This is obviously not a characterization of the notion of a non-linear expansion. I think it possible to provide some such characterization, at least given a certain level of idealization and a number of philosophical decisions, but this would require a richer formal framework than the one introduced here.

It might be objected that Agilulf, the nonexistent knight of the eponym novel by Italo Calvino, provides a counter-example to this analysis. The reason is that it appears that Agilulf has been created by Calvino even though in the story he is nonexistent. This objection has some initial plausibility, but it does not stand close scrutiny. Like any other character of a fictional work, in the work Agilulf is an agent, and as such has a number of existence-entailing properties (being sentient, having causal efficacy, and so on). Thus either the story is inconsistent, and Agilulf both exists and does not exist therein, or “nonexistent” is to be understood in a somewhat idiosyncratic way, for instance as a synonym of “immaterial.” Either way, the counter-example is blocked.

This is not to say that it is completely neutral, however. Among other things, it presupposes an indeterministic and possibilist framework that may or may not suit one’s metaphysical tastes. (Albeit, of course, nothing forbids adopting an instrumentalist or fictionalist understanding of this presupposition.)

The aforementioned theory \(\mathbf{TFM}^{-} \)(p. 10) and the corresponding \(\mathbf{OTF}^{-}\) frames are easily obtained from TFM and \(\mathbf{OTF}\) frames by dropping the axiom Tree and the frame property TREE, respectively (see below, pp. 20–23). It is straightforward, and left to the reader, to extend the proofs of soundness and completeness for TFM to \(\mathbf{TFM}^{-} \).

Note that here the symbols \(<, \sim , \ldots , {\overset{_{\curvearrowright }}{_{\,f_{\;s}}}}\) are not understood to denote the same relations as in Definition 6 (unless \(\mathcal {N}\) is perfect, see Definition 19). This (harmless) ambiguity is allowed too keep terminological complexity to a minimum.

References

Belnap, N., Perloff, M., & Xu, M. (2001). Facing the future: Agents and choices in our indeterminist world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bertolet, R. (1984a). Inferences, names, and fictions. Synthese, 58(2), 203–218.

Bertolet, R. (1984b). On a fictional ellipsis. Erkenntnis, 21(2), 189–194.

Blackburn, P., de Rijke, M., & Venema, Y. (2001). Modal logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blocker, G. (1974). The truth about fictional entities. The Philosophical Quarterly, 24(94), 27–36.

Bonomi, A., & Zucchi, A. (2003). A pragmatic framework for truth in fiction. Dialectica, 57(2), 103–120.

Brock, S. (2002). Fictionalism about fictional characters. Noûs, 36(1), 1–21.

Brock, S. (2010). The creationist fiction: the case against creationism about fictional characters. Philosophical Review, 119(3), 337–364.

Broersen, J. (2008a). A logical analysis of the interaction between ‘obligation-to-do’ and ‘knowingly doing’. In R. van der Meyden & L. van der Torre (Eds.), Deontic logic in computer science: 9th international conference, DEON 2008 (pp. 140–154). Berlin: Springer.

Broersen, J. (2008b). A complete stit logic for knowledge and action, and some of its applications, Declarative agent languages and technologies VI, DALT 2008 (pp. 47–59). Berlin: Springer.

Broersen, J. M. (2011). Making a start with the stit logic analysis of intentional action. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 40(4), 499–530.

Chellas, B. (1969). The logical form of imperatives. Stanford: Perry Lane Press.

Chellas, B. (1992). Time and modality in the logic of agency. Studia Logica, 51(3), 485–517.

Currie, G. (1989). An ontology of art. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Currie, G. (1990). The nature of fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Currie, G. (2003). Characters and contingency. Dialectica, 57(2), 137–148.

Currie, G. (2010). Narratives and narrators. A philosophy of stories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Maio, M. C., & Zanardo, A. (1994). Synchronized histories in Prior-Thomason representation of branching time. In D. Gabbay & H. Ohlbach (Eds.), Proceedings of the First International Conference on Temporal Logic (pp. 265–282). Berlin: Springer.

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Everett, A. (2005). Against fictional realism. The Journal of Philosophy, 102(12), 624–649.

Everett, A. (2013). The nonexistent. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gabbay, D. (1981). An irreflexivity lemma with applications to axiomatizations of conditions on tense frames. In U. Mönnich (Ed.), Aspects of philosophical logic (pp. 67–89). Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Hill, B. (2012). Fiction, counterfactuals: the challenge for logic. In Special sciences and the unity of science (pp. 277–299). Dordrecht: Springer.

Horty, J. (1989). An alternative stit operator. Manuscript, Philosophy Department, University of Maryland.

Kivy, P. (2006). The performance of reading. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and necessity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kripke, S. (2011). Philosophical troubles: collected papers (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kroon, F. (2011). The fiction of creationism. In F. Lihoreau (Ed.), Truth in fiction (pp. 203–221). Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Kroon, F., & Voltolini, A. (2011). Fiction. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/fiction/.

Lewis, D. (1978). Truth in fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly, 15(1), 37–46. Reprinted, with postscripts, in D. Lewis (1983), Philosophical papers (Vol. I, pp. 261–280). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nossum, R. (2003). A contextual approach to the logic of fiction. In Modeling and using context (pp. 233–244). Dordrecht: Springer.

Predelli, S. (1997). Talk about fiction. Erkenntnis, 46(1), 69–77.

Predelli, S. (2008). Modal monsters and talk about fiction. The Journal of Philosophical Logic, 37(3), 277–297.

Prior, A. (1967). Past, Present, and Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reicher, M. (2008). Nonexistent objects. In Zalta, E.N. (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/nonexistent-objects.

Richard, M. (2000). Semantic pretense. In T. Hofweber & A. Everett (Eds.), Empty Names, fiction, and the puzzles of non-Existence (pp. 205–232). Stanford: CSLI.

Ross, J. (1997). The semantics of media. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Salmon, N. (1998). Nonexistence. Noûs, 32(3), 277–319.

Stanley, J. (2001). Hermeneutic fictionalism. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 25(1), 36–71.

Thomasson, A. (1999). Fiction and metaphysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomasson, A. (2003). Speaking of fictional characters. Dialectica, 57(2), 205–223.

van Inwagen, P. (1977). Creatures of fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly, 14(4), 299–308.

Voltolini, A. (2006). Fiction as a base of interpretation contexts. Synthese, 153(1), 23–47.

Von Kutschera, F. (1986). Bewirken. Erkenntnis, 24(3), 253–281.

Walton, K. (1990). Mimesis as make-believe: on the foundations of the representational arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wansing, H. (2002). Seeing to it that an agent forms a belief. Logic and logical philosophy, 10, 185–197.

Wansing, H. (2006). Doxastic decisions, epistemic justification, and the logic of agency. Philosophical Studies, 128(1), 201–227.

Wolterstorff, N. (1980). Works and worlds of art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woods, J. (1974). The logic of fiction: a philosophical sounding of deviant logic. The Hague: Mouton.

Woods, J., & Alward, P. (2004). The logic of fiction. In D. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of philosophical logic (Vol. 11, pp. 241–316). Dordrecht: Springer.

Yagisawa, T. (2001). Against creationism in fiction. Noûs, 35(15), 153–172.

Zanardo, A. (1991). A complete deductive system for since-until branching-time logic. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 20(2), 131–148.

Zanardo, A. (1996). Branching-time logic with quantification over branches: The point of view of modal logic. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 61(1), 1–39.

Acknowledgments

I am especially indebted to Pierdaniele Giaretta and Alberto Zanardo. Without their help and encouragement this paper would not exist. I also express my gratitude to Roberto Ciuni, Giuliano Torrengo, Graham Priest, and Alessandro Zucchi for their insightful comments and suggestions. Last but not least, I am deeply indebted to three anonymous referees for Synthese, which significantly helped to improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spolaore, G. Agency and fictional truth: a formal study on fiction-making. Synthese 192, 1235–1265 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-014-0613-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-014-0613-0