Abstract

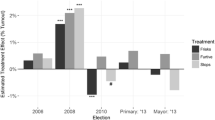

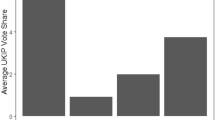

States vary in their treatment of the voting rights of convicted felons through incarceration, probation, parole, and beyond. A few states permit even incarcerated felons to vote, while others rescind the right permanently, with most states’ policies located between those extremes. This paper analyzes the relationship among voter turnout, election outcomes, and levels of felon disenfranchisement by state. The results show a pattern of divergence around the 2000 election before which turnout, disenfranchisement, crime rates, and Republican or Democratic success in elections were unrelated and since which strong correlations are found. Disenfranchisement rates no longer bear a significant relationship to crime rates, and states won by Republicans have both lower overall turnout and higher levels of ineligible felons in the voting-age population. Partisan control of state legislatures does not predict these patterns, but there is a strong regional component to the data with disenfranchisement notably higher in Southern states regardless of partisan control. Overall the data support a need for further research on the disparate treatment of felon voting rights among states which may be contributing to broader trends emerging in political science research of a growing relationship between lower voter turnout and Republican electoral success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

E.g., Johnson v. Bush, 02-14469 [11th Cir., December 19, 2003].

This is not intended as a comprehensive summary of the legal history of this issue, and the author is thankful to legal scholars including Miles (2004) who have undertaken that task.

Current as of December 31, 2016. Source: State attorneys general websites, plus District of Columbia.

The relative difficulty and complexity of these procedures are not considered here but are a relevant topic for further research on interstate differences in rates of disenfranchisement and participation.

Data from the US Elections Project calculate disenfranchisement rates as the number of ineligible felons as a percentage of all adults of voting age in each state.

It is possible, of course, that causality flows in either direction on this point; GOP-dominated states may be more likely to pass disenfranchising laws, or states with such laws may be more favorable to GOP candidates. For the scope and purpose of this analysis, the intention is to investigate whether any relationship is found in the data at all. If so, determining the causal mechanisms will be an important topic for further research.

These and all other data are available upon request from the author and online at (insert).

Data source: FBI Uniform Crime Reporting statistics, via http://www.fbi.gov.

Like the U.S. House of Representatives, nearly all state legislatures have two-year terms for one or both chambers of the legislature, creating the potential for partisan control to change with each presidential and midterm election.

For a list and official definitions, see Census Regions and Census Divisions.

See also Vote View blog, “Collapse of the Voting Structure” for record high levels of polarization as measured by DW-Nominate scores, 1/12/2017.

References

Aldrich, J. H., & Rohde, D. W. (1997). The transition to Republican rule in the House: Implications for theories of congressional politics. Political Science Quarterly, 112(4), 541–567.

Bechtel, M. M., Hangartner, D., & Schmid, L. (2015). Does compulsory voting increase support for leftist policy? American Journal of Political Science onlinefirst. doi:10.1111/ajps.12224.

Behrens, A., Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2003). Ballot manipulation and the ‘Menace of Negro Domination’: Racial threat and felon disenfranchisement in the United States, 1850–2002. American Journal of Sociology, 109(3), 559–605.

Burch, T. (2010). Did disfranchisement laws help elect President Bush? New Evidence on the turnout rates and candidate preferences of Florida’s ex-felons. Political Behavior, 34(1), 1–26.

Burmila, E. (2014). Surge and decline: The impact of changes in voter turnout on the 2010 Senate elections. Congress & The Presidency, 41(3), 289–311.

Citrin, J., Schickler, E., & Sides, J. (2003). What if everyone voted? Simulating the impact of increased turnout in senate elections. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 75–90.

DeNardo, J. (1980). Turnout and the vote: The joke’s on the democrats. American Political Science Review, 74(2), 406–420.

Druckman, J., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Fowler, A. (2015). Regular voters, marginal voters and the electoral effects of turnout. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 205–219. doi:10.1017/psrm.2015.18.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Meredith, M., Biggers, D. R., & Hendry, D. J. (2015). Can incarcerated felons Be(Re)integrated into the political system? Results from a field experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 912–926. doi:10.1111/ajps.12166.

Goldman, D. S. (2004). The modern-day literacy test?: Felon disenfranchisement and race discrimination. Stanford Law Review, 57(2), 611–655.

Hajnal, Z., Lajevardi, N., & Nielson, L. (2017). Voter Identification laws and the suppression of minority votes. The Journal of Politics. doi:10.1086/688343.

Harvey, A. E. (1994). Ex-felon disenfranchisement and its influence on the black vote: The need for a second look. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 142(3), 1145–1189.

Highton, B., & Wolfinger, R. E. (2001). The political implications of higher turnout. British Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 179–192.

Karlan, P. S. (2004). Convictions and doubts: Retribution, representation, and the debate over felon disenfranchisement. Stanford Law Review, 56(5), 1147–1170.

Lijphart, A. (1997). Unequal participation: Democracy’s unresolved dilemma. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 1–14.

Manza, J., Brooks, C., & Uggen, C. (2004). Public attitudes toward felon disenfranchisement in the United States. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(2), 275–286.

Manza, J., & Uggen, C. (2006). Locked out: Felon disenfranchisement and American democracy. London: Oxford University Press.

Miles, T. J. (2004). Felon Disenfranchisement and voter turnout. Journal of Legal Studies, 33(1), 85–129.

Phillips, A. J., & Deckard, N. (2015). Felon disenfranchisement laws and the feedback loop of political exclusion: The case of Florida. Journal of African American Studies, 20(1), 1–18.

Piven, F. F., & Cloward, R. A. (1988). Why Americans don’t vote. New York: Pantheon.

Rodon, T. (2015). When the kingmaker stays home revisiting the ideological bias on turnout. Party Politics. doi:10.1177/1354068815576291.

Terry, W. C. (2016). Yes, structurally low turnout favors the right. Politics, Groups, and Identities. doi:10.1080/21565503.2015.1124789.

Theriault, S. M. (2006). Party polarization in the US Congress member replacement and member adaptation. Party Politics, 12(4), 483–503.

Theriault, S. M. (2008). Party polarization in Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Theriault, S. M. (2013). The Gingrich senators: The roots of partisan warfare in Congress. London: Oxford University Press.

Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2002). Democratic contraction? Political consequences of felon disenfranchisement in the United States. American Sociological Review, 67(6), 777–803.

Wheelock, D. (2005). Collateral consequences and racial inequality felon status restrictions as a system of disadvantage. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 21(1), 82–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Human and Animal Rights Statements

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Ethical Approval

The research and manuscript were conducted and prepared in accordance with all ethical guidelines stated in the Social Justice Research “Instruction for Authors.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burmila, E.M. Voter Turnout, Felon Disenfranchisement and Partisan Outcomes in Presidential Elections, 1988–2012. Soc Just Res 30, 72–88 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-017-0277-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-017-0277-2