Abstract

The magnitude of climate change threats to life on the planet is not matched by the level of current mitigation strategies. To contribute to our understanding of inaction in the face of climate change, the reported study draws upon the pro status quo motivations encapsulated within System Justification Theory. In an online questionnaire study, participants (N = 136) initially completed a measure of General System Justification. Participants in a “System-critical” condition were then exposed to information linking environmental problems to the current economic system; participants in a Control condition were exposed to information unrelated to either environmental problems or the economic system. A measure of Economic System Justification was subsequently administered. Regressions of Economic System Justification revealed interactions between General System Justification and Information Type: higher general system justifiers in the System-critical condition rated the economic system as less fair than did their counterparts in the Control condition. However, they also indicated inequality as more natural than did their counterparts in the Control condition. The groups did not differ in terms of beliefs about the economic system being open to change. The results are discussed in terms of how reassurance about the maintenance of the status quo may be bolstered by recourse to beliefs in a natural order.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is considered one of the greatest threats to life on the planet. Most climate scientists agree that average global temperatures are increasing due to anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions (IPCC, 2013) and are of the view that people face significant further climate change in future (Meehl et al., 2005). It seems that the planet per se will survive but the planet that provides our habitat is under severe threat. Nevertheless, climate change is sometimes reported as located at the bottom of the range of personal and social concerns among the public in survey research (e.g. Poortinga & Pidgeon, 2003). How is this apparent paradox to be understood?

Klein (2014) and Merchant (2005), among others, discuss how social injustice and environmental destruction are inherent in industrial production under capitalism. It has been suggested, moreover, that the people who are already most disadvantaged by capitalism are also the most vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, while they contribute the least to emissions (Klein, 2014; Norgaard, 2011).

Capitalism here may be understood as a system that endorses the profit and growth motive within a free market economy. Some political economists argue that globalisation is the latest development in the history of capitalism and that it needs to be understood as the context in which current environmental destruction is both created and addressed: “…it is patterns of production, trade and flows of finance, and their governance and un-governance by a growing range of actors that are most central to the interface between globalization and ecology, as the structures that literally create environmental change and shape the context in which it can be responded to” (Newell, 2012, pp. 7–8). Kasser, Cohn, Kanner and Ryan (2007) note that the psychological literature often fails to acknowledge (and therefore to study) capitalism’s influence on culture, norms, values and ultimately on the way people think and behave.

Even among those who accept the anthropogenic causes of climate change, many seek market-based solutions (e.g. carbon trading or the purchase of “green” consumer products) to environmental problems. However, Klein (2014) points to the failure of market mechanisms such as “cap and trade” and argues that neither technological “solutions” nor transitions to greener consumer lifestyles alone will address the root problem that is causing environmental destruction (see also, e.g. Shove, 2010; Webb, 2012). The fundamental issues are how—or whether—constant economic growth can (or should) be sustained in a world with finite “resources” and which rights, laws and power relations are in place to allow access to land and water to some people and not to others. The link between the dominant economic–political system and environmental destruction is rarely salient in public discourse partly; it has been suggested because of the lobbying of politicians and the media by the fossil fuel industry (Klein, 2014; Monbiot, 2006; Oreskes & Conway, 2010).

System Justification Theory

System Justification Theory (SJT; Jost & Banaji, 1994) provides an additional approach to inaction in relation to social justice and climate change (Feygina, 2013). SJT proposes that people are motivated to defend the status quo or “the existing social order” (Jost, Banaji & Nosek, 2004, p. 881). The theory involves ideas about “social and psychological needs to imbue the status quo with legitimacy and to see it as good, fair, natural, desirable, and even inevitable” (Jost et al., op. cit., p. 887). These purported needs, in turn, are seen as arising out of “epistemic” and “existential” motives [for example, for “certainty and security” (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski & Sulloway, 2003, p. 351)].

Jost and Hunyady (2005) suggest that “people who possess heightened needs to manage uncertainty and threat are especially likely to embrace conservative, system-justifying ideologies (including right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and economic system justification). More specifically, uncertainty avoidance; intolerance of ambiguity; needs for order, structure, and closure … are all positively associated with the endorsement of these ideologies” (p. 261). Importantly, system justification tendencies are proposed to be held not only by those advantaged, but also by those most disadvantaged by existing social arrangements (Jost, Pelham, Sheldon & Sullivan, 2003). Despite this purported general motivation to justify the status quo, people vary in this tendency due to individual differences (e.g. in the need to avoid and manage uncertainty, ambiguity and threat) and situational factors (e.g. system threat).

Individual Differences: Lower Versus Higher System Justification Tendencies

Some individuals react to system threat with particular kinds of system justification more so than do others (Hennes, Nam, Stern & Jost, 2012; Jost, Gaucher & Stern, 2015). For example, Banfield, Kay, Cutright, Wu and Fitzsimons (2011) found that people low in General System Justification were more defensive of the status quo (e.g. in terms of choosing domestic over international products) after exposure to a threat manipulation compared to people in the Control condition, while there was no effect of the threat manipulation on people high in system confidence. The authors proposed that, in line with SJT, this effect occurs because low-system justifiers are also motivated to defend the status quo, but are further away from achieving that goal and therefore react more defensively when the system is threatened. Similarly, van der Toorn, Nail, Liviatan and Jost (2014) found that in response to System-critical information, liberals increased their patriotism (which they interpret as system defence) to the level of that of conservatives, suggesting that liberals can react defensively to system threat.

However, there is also evidence of a different pattern of effects. Yoshimura and Hardin (2009) demonstrated that when Japan’s subjugation to the USA was made cognitively salient (compared to when Japan’s superiority was made salient), Japanese participants who scored higher (compared to lower) on General System Justification showed stronger out-group favouritism (i.e. support for the status quo of US hegemony). Further, studies have shown that the psychological mechanisms posited to underlie system justification tendencies are also heightened in conservatives; for instance, that they display greater loss and death anxiety, more intolerance of uncertainty and greater needs for closure and order compared to liberals (Jost, Glaser, et al., 2003). Conservatives in contrast to liberals have been found to be more in favour of punishment of deviance, more predisposed to rationalise inequity and more favourable towards prevailing power hierarchies (Jost, Glaser, et al., 2003; Jost & Hunyady, 2005). Correspondingly, studies have found a correlation between conservatism and General and Economic System Justification (Feygina, Jost & Goldsmith, 2010; Jost, Nosek & Gosling, 2008). Additionally, Hennes et al. (2012) found that lower need for cognition, greater death anxiety and stronger relational needs were related to higher Economic System Justification, which was associated with greater support for the Tea-Party, opposition to Occupy Wall Street and various other issues such as rejection of the idea of anthropogenic climate change.

Friedman and Sutton (2013) note that threats to the dominant social structures ought not to consistently stimulate system justification tendencies, because of individual differences: “Rather, whereas threats to the status quo may promote increased accessibility of and adherence to system-justifying ideologies among staunch conservatives, they may have no effect or even the very opposite effect among staunch liberals, in whom they may facilitate efforts at system delegitimization” (p. 354). In support of their hypotheses, the authors did indeed find that after exposure to a threat manipulation, conservatives were more defensive of the status quo than were conservatives in the Control condition, while the manipulation had no effect on liberals. Specifically, their threat manipulation involved exposure to luxury advertisements next to a news article about civilian deaths in the US-led war on Afghanistan. The contrast between the advertisement and news report was expected to make apparent the disparity between the “haves” and the “have nots”, which would undermine the legitimacy of the status quo. The authors suggested that people with higher system justification tendencies (conservatives) would be more tolerant of civilian deaths (i.e. defend the system’s integrity) following a system threat, compared to individuals who were more open to criticising the system (liberals). They found that exposure to the luxury advertisement and news article (compared to control stimuli) significantly increased conservatives’ acceptance of civilian deaths, while it had no effect on liberals.

Further, these individual differences in system justification tendencies have real-world practical implications: Hennes et al. (2012) suggest “that those who are chronically low with respect to epistemic, existential, and relational needs might be especially high when it comes to the motivation to change the system, and this could explain both their rejection of the status quo and their support for the Occupy Wall Street movement” (p. 682).

Situational Factors

There is ample evidence in history of where low-status groups and people with differing political beliefs have not legitimised and justified the social system but rather rebelled and changed it (Zimmerman & Reyna, 2013). For instance, Zimmerman and Reyna (2013) showed that low-status groups perceived a larger discrepancy between prescribed values (such as equality, meritocracy and democracy) and actual circumstances in the USA, were more dissatisfied with the status quo and more in favour of policies that would change existing hierarchies, than were high-status groups (contrary to Jost, Pelham, et al., 2003). Martorana, Galinsky and Rao (2005) examined the circumstances under which disadvantaged low-power groups take action: they suggest that perceptions of power, illegitimacy, instability and impermeability, as well as emotions such as anger, predict actions against authority and oppressive systems. Johnson and Fujita (2012) explored “system–change motivation” (p. 133), whereby people are motivated to alter and improve on the status quo. In one study, they found that with increased perceptions of changeability, participants were more likely to choose System-critical rather than system-supportive information, thereby indicating a condition under which the avoidance of System-critical information might be circumvented (cf. Shepherd & Kay, 2012). Further, Kay and Friesen (2011) showed that when exit strategies are available (compared to a situation in which a system appears inescapable), participants were less likely to justify the system. Additionally, Brandt (2013) analysed survey data from 65 countries (including the USA) with a large sample size and only found one out of fourteen effects to be consistent with System Justification Theory. He concluded that findings suggest that low-status groups defend the system as much as, or more than, high-status groups are not robust.

System Justification Theory and Environmental Issues

Why might SJT be a useful addition to psychological research on environmental attitudes and behaviour? Feygina (2013) suggests that people’s disregard of the environment, despite their dependence on it, is based on a historical development of ideology and society which expresses itself on a psychological level: “…attitudinal and motivational responses to social systems and hierarchies that underlie the perpetuation of social injustice appear to also account for ongoing environmental destruction and resistance to pro-environmental change” (p. 364).

Psychological research has sometimes been criticised for focusing on individual-level engagement (for example, promoting individuals’ pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour with respect to recycling, domestic energy conservation and use of public transport) while ignoring systemic factors such as the economic growth motive (Shove, 2010; Webb, 2012) or subsidies to the fossil fuel industry (Carrington, 2015). Since SJT offers a perspective on attitudes towards structural level change, its relevance to the environmental debate merits more attention.

Under the current economic system, the environment is treated as an externality with issues of waste absorption and maintenance of ecosystems being disregarded (Jacobs, 1991). Klein (2014) argues that tackling environmental destruction effectively would require both changing current modes of production and consequently the consumption habits embedded in capitalism. Feygina et al. (2010) maintain that addressing environmental issues could be perceived as a threat to the social, economic and political functioning of modern Western societies. They suggest that in wanting to perceive societal and economic structures as fair, people downplay the existence of environmental problems and fail to take responsibility or action. Indeed, the problem of different forms of denial is apparent in a wide range of perspectives on environmental threat (Dunlap, 2013; Gladwin, Newburry & Reiskin, 1997; Leiserowitz, Maibach, Roser-Renouf & Smith, 2011; Norgaard, 2011; Sparks, Jessop, Chapman & Holmes, 2010). Defending the status quo could lead to continued unresponsiveness and hinder the formation of change both in relation to social justice and environmental issues.

Feygina et al. (2010) found that General System Justification and Economic System Justification predicted greater denial of environmental problems and more reluctance to engage in pro-environmental behaviours. In one study (Study 3), they framed pro-environmental behaviour as patriotic (in the sense of upholding the North American way of life) and therefore as protecting the status quo. The authors suggested that this framing overcomes the threat often posed by environmental messages, increases the acceptance of the latter and promotes beneficial intentions. They found that higher system justifiers did indeed show stronger pro-environmental intentions when pro-environmental behaviour was portrayed as a means of maintaining the status quo, than when it was not. Feygina et al. (2010) suggest that “reframing environmentalism as supporting (rather than undermining) the American way or (sic) life eliminates the negative effect of system justification on pro-environmental behavior” (p. 334). Further, the authors state that “Importantly, much of the problem concerns the perception of incompatibility, and our findings … provide some evidence that this perception is potentially subject to revision. Reframing environmentalism as patriotic and a means of protecting our “way of life” eliminates the negative association between system justification and the desire to help the environment.” (p. 335). It might be argued that one possible pitfall with this approach is that the original perception is correct: that is, the current system and environmentalism are incompatible (Clark & York, 2005; Merchant, 2005). As argued above, environmentalism is neither a means of protecting the American “way of life” nor any system that supports it. Klein (2014) is more trenchant: “The far more troubling problem with this approach is that rather than challenging the warped values fueling both disaster denialism and disaster capitalism, it actively reinforces those values …” (p. 58). It may thus be of greater long-term value to investigate how to increase people’s recognition of the dominant economic system’s shortcomings by drawing upon the individual differences and situational factors that make people more open to criticism of the system and to system change.

Framing of Information

It has been argued that there is an important connection between the acknowledgement of anthropogenic climate change and recognition of problems with the dominant economic system: “… climate change denial can be seen as part of a more sweeping effort to defend the modern Western social order (Jacques 2006), which has been built by an industrial capitalism powered by fossil fuels (Clark & York 2005). Since anthropogenic climate change is a major unintended consequence of fossil fuel use, simply acknowledging its reality poses a fundamental critique of the industrial capitalist economic system” (Dunlap & McCright, 2011, pp. 144–145).

Further, perceiving climate change as a threat to the status quo may be greater among right-wing people who tend to be higher in anthropogenic climate change denial and scepticism (Dunlap & McCright, 2008; Klein, 2014; McCright & Dunlap, 2011a, b). People subscribing to more left-wing political ideologies might feel less threatened by climate change information and structural change suggestions since they already tend to be more sympathetic towards a social change agenda (as argued above). Additionally, Johnson and Fujita (2012) found that when people perceived a system to be changeable, they preferred information critical of the status quo. They suggest that this is in line with a motivation to change and to improve the status quo over time. Accordingly, it is possible that lower system justifiers, who receive System-critical information linked with possibilities for change, may be more open to that information than are higher system justifiers. Those lower system justifiers may subsequently be less defensive, and more critical, of the economic system.

The Present Study

The research reported here is located within the view that in order to address climate change and social injustice it is crucial to examine the role of social structural issues, such as industrial production and capitalism. Thus, criticism of the status quo may be a necessary condition for tackling social and environmental injustice. The more specific aim of this study is to contribute to the examination of the boundary conditions of system justification. It examines possibilities for criticism of the economic system in the context of the failure of the capitalist market logic presented by climate change (Klein, 2014), by inspecting cases in which providing information about the link between the economic system and climate change can moderate justification of the economic system.

The study reported here investigates the effects of the interaction between level of system justification and Information Type on Economic System Justification. It is congruent with Friedman and Sutton’s (2013) findings that conservatives but not liberals responded to threat with increased defensiveness. It is also compatible with Johnson and Fujita’s (2012) research examining system change motivation and Zimmerman and Reyna’s (2013) and Brandt’s (2013) findings that disadvantaged groups can be more critical of and dissatisfied with a system and more supportive of change than are high-status groups.

Our main hypothesis was that there would be an interaction between Information Type (System-critical information vs. Control information) and General System Justification (lower vs. higher) on Economic System Justification. As part of this, we expected that information about the link between capitalist economic systems and anthropogenic climate change would lead to greater Economic System Justification in people higher on General System Justification than would Control information. We also expected that this effect would be non-existent or reversed among lower General System Justification participants, who would be more open to—and less defensive in response to—the System-critical information.

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirty-six participants (67.6 % female; 86.8 % students) in the UK were recruited via email to take part in a study investigating attitudes towards contemporary issues. Participants were contacts of the first author, or contacts of those contacts (a “snowball” method was used to extend recruitment). Their ages ranged between 18 and 65 years (M = 24.15, SD = 8.25 years). Participation was on a voluntary basis, with the option of entering a £25 (about $40) prize draw as an incentive.

Materials

The study was conducted using an online questionnaire. All responses on the measures listed below were given on seven-item response scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Items were reverse-coded as appropriate. A measure of climate change scepticism was also included, but findings from this measure are not discussed further.

Political Orientation

Political orientation was measured using the Conservatism–Liberalism Scale (Mehrabian, 1996), consisting of seven items, e.g. “In any election, given a choice between a right-wing and a left-wing candidate, I will select the right-wing over the left-wing candidate”, α = .87. Higher scores indicate a more conservative political orientation.

General System Justification (GSJ)

Eight items measured General System Justification, e.g. “In general, I find society to be fair” (Kay & Jost, 2003), α = .75. Higher scores indicate a higher level of system justification.

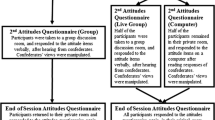

Once participants had completed these measures, they took part in one of two experimental conditions:

System-Critical Information Condition

Participants (n = 62) read a piece of text (643 words), which discussed the relationship between the dominant economic system and environmental problems (adapted from a text by Magdoff & Foster, 2010; see Table 1). Simple questions about the text were inserted between sections to ensure that participants had read the information.

Control Condition

Participants (n = 75) read a piece of information unrelated to the study (647 words), which discussed the history of a city in south-east England (see Table 2). Again, questions were included to ensure that the text had been read.

Having read the text, participants completed the following dependent measure:

Economic System Justification

Sixteen items measured Economic System Justification (Jost & Thompson, 2000), e.g. “If people work hard, they almost always get what they want”, α = .88. Higher scores indicate a higher level of Economic System Justification.

Design and Procedure

The study involved two independent variables: General System Justification (as a continuous variable) and Information Type (as a two-level categorical factor).Footnote 1 Following the manipulation of Information Type, participants completed the Economic System Justification measure. The questionnaire took participants approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To examine whether there were any systematic differences between Information Type conditions, the distributions of age and gender were analysed. There was no significant difference in the distribution of gender, χ 2(1) = .34, p = .558, or age, t(133) = −0.55, p = .585, between the two conditions. Principal component analyses (PCA) were conducted on every scale used in the study to examine whether they consisted of one or several underlying components. Only the Economic System Justification scale consisted of more than one component. Following the preliminary analysis for PCA, one item was excluded from the Political Orientation scale as it correlated <.30 with all other items (to create a modified Political Orientation scale). Similarly, two items were excluded from the GSJ scale because they correlated <.30 with all other items (to create a modified GSJ scale).

PCA of Economic System Justification Items

A PCA using orthogonal rotation was conducted on the Economic System Justification items. One item was excluded due to low correlations with all other items, and from now on we refer to this modified Economic System Justification scale. Sampling adequacy was good (KMO = .88), and all individual items’ KMO values were acceptable (>.83). Correlations between items were adequate for PCA, χ 2(120) = 782.54, p < .001. Three components were retained as they had eigenvalues >1 (and the screeplot was ambiguous). Jointly, they explained 53.85 % of the variance (Table 3 shows the factor loadings after rotation). The first component appeared to reflect beliefs in the Fairness of the System, the second component beliefs about the Possibility of Change and the third component beliefs about Inequality as Natural.

Predicting Economic System Justification

Multiple regressions of the three Economic System Justification components were conducted to explore the effect of Information Type (unrelated information [0], System-critical information [1]), General System Justification (mean centred) and their interaction. Where there were significant interaction effects, further comparisons of the simple slopes were conducted for the dependent variable at higher and lower levels of General System Justification (1 SD above and below the mean, M = 2.83, SD = 1.12).

Fairness of the System Beliefs

General System Justification was a significant predictor of judgements of Fairness of the System, β = .74, t = 8.36, p < .001, with higher GSJ scores being associated with stronger beliefs in the fairness of the system. Information Type was not a significant predictor, β = −.08, t = −1.18, p = .240. However, there was a significant interaction between Information Type and General System Justification, β = −.22, t = −2.47, p = .015 (Fig. 1). For higher system justifiers, there was a significant effect of Information Type, with weaker beliefs in the Fairness of the System in the System-critical information condition than in the Control condition, β = −.25, t = −2.53, p = .012. For lower system justifiers, Information Type had no significant effect, β = .09, t = 0.95, p = .345.

Possibility of Change Beliefs

Neither General System Justification, β = −.05, t = −0.42, p = .673, nor Information Type, β = −.01, t = −0.11, p = .915, were significant predictors of Possibility of Change beliefs, and there was no significant interaction between the two, β = .14, t = 1.21, p = .230 (Fig. 2).

Inequality as Natural Beliefs

General System Justification was a marginally significant predictor of beliefs about Inequality as Natural, β = .19, t = 1.72, p = .088, indicating that greater GSJ was associated with stronger beliefs that inequality is natural. Information Type was not a significant predictor, β = .09, t = 1.13, p = .261. However, the analysis yielded a significant interaction between Information Type and General System Justification, β = .21, t = 1.95, p = .054 (Fig. 3). Higher system justifiers expressed significantly stronger Inequality as Natural beliefs in the System-critical information condition than they did in the Control condition, β = .26, t = 2.14, p = .035. There was no significant difference for lower system justifiers between the two conditions, β = −.07, t = −0.61, p = .545.

The Relationship Between Political Orientation and GSJ

GSJ was significantly related to Political Orientation, rs = .55, p < .001, indicating that higher GSJ scores were related to higher political conservatism scores.

Discussion

In this study, PCA revealed three dimensions to the Economic System Justification scale. One component related to judgements of the Fairness of the System, another to the Possibility of Change and a third component to Inequality as Natural. Analyses showed that GSJ was a significant predictor of beliefs in the Fairness of the System and in Inequality as Natural (but not of beliefs in Possibilities of Change). Most importantly, there was a significant interaction between Information Type and GSJ on beliefs about the Fairness of the System and about Inequality as Natural. Notably, although higher GSJ participants exposed to the System-critical information judged the economic system to be less fair than did those reading the Control information, they were also more prone to regard inequality as a natural phenomenon. Interestingly, the findings indicate that higher GSJ participants seem to have been swayed by the information in acknowledging unfairness in the economic system. However, the findings also showed that higher GSJ participants reacted to System-critical information by indicating stronger beliefs in the idea that inequality is natural. This is interesting in light of the suggestion that system justification involves people’s motivation “to view the social systems that affect them as fair, legitimate, natural, and desirable” (Jost et al., 2015, p. 321). Our findings provide a hint that if parts of this belief system are rendered difficult (e.g. beliefs about the fairness of a system), then other aspects (such as perceptions of naturalness) may be heightened. Thus, for example, threats to the perceived legitimacy of a system may be offset by a strengthening in the belief of the system’s stability; system justification theorists acknowledge both these motives (Jost & Banaji, 1994).

It should be noted that this reference to the motive to see parts of the status quo as “natural” goes back to the original Jost and Banaji (1994) work, as well as having resonances in recent views about injunctification, the idea that “people may be motivated to view the status quo, even if unfair, as the most desirable state of affairs” (Kay et al., 2009, p. 421). Additionally, Wakslak, Jost and Bauer (2011) found that critiques of one part of the social system caused people to bolster other parts of the social system. In reference to that study, Jost et al. (2015) suggest that “a threat to the legitimacy or stability of one aspect of the social system stimulates defensive responding on behalf of other parts of the system” (p. 330). An analogous argument could be made in light of the current findings: that when one system feature (e.g. its fairness) is questioned or discredited, people who are more motivated to defend the system (i.e. higher system justifiers) increase attention to other ideas about the system (in this case the naturalness of inequality within the system). Moreover, these notions regarding the legitimacy and naturalness of the broader economic system are socially reinforced: “Much of the literature on globalization seeks to present it as apolitical, natural and inevitable” (Newell, 2012, p. 10).

Our findings showed that Information Type did not influence lower system justifiers’ ratings. It is possible that the System-critical information merely reaffirmed their views, rather than change their views. This is somewhat at odds with research by Banfield et al. (2011) who proposed that low general system justifiers are further away from attaining the goal of system justification and thus might be expected to show greater need than high general system justifiers to defend the status quo when this is threatened. However, our findings are congruent with Friedman and Sutton’s (2013) findings which showed that conservatives (who, the authors suggest, have stronger system justification motives) were more defensive of the status quo after exposure to a system threat manipulation compared to liberals (purported to be more open to challenging the status quo).

In the present study, given the different responses between lower and higher system justifiers in their judgements of fairness and inequality, it is interesting that they did not differ in their beliefs about the possibilities for change. Such beliefs are important, as Johnson and Fujita (2012) have shown that they can influence people’s choice of information: in their research, people were more likely to seek negative information about a system when they perceived a greater possibility of change within that system. In keeping with the findings of Feygina et al. (2010), but using a UK sample, it is also noteworthy that political conservatism was significantly associated with higher GSJ in the present study.

We should also acknowledge some limitations of our research. Firstly, the sample consisted largely of students and thus is not representative of the UK public at large. Secondly, it is necessary to tease apart how information about the possibilities of change exactly influence justification processes. Future research could examine lower and higher system justifiers responses to System-critical information separately to the provision of information about alternatives, as well as testing what kind of concessions are made towards criticising the system and to what extent offsetting mechanisms occur to bolster the system some other way. Understanding system justification strategies has practical relevance because acknowledging shortcomings of the status quo may be crucial in order to increase support for broader social change and action on climate change.

In conclusion, the potential threat posed by the information about the detrimental effects of the current economic system did not prevent higher system justifiers (as a group) from acknowledging the unfairness of the system. Notably, higher system justifiers also did not show weaker beliefs in the possibility of change than did lower system justifiers. However, higher system justifiers demonstrated greater beliefs in Inequality as Natural following exposure to such information (compared to their higher system justifier counterparts in the Control condition). Perhaps some people find solace in the idea of social order being predicated on some natural order, or of nature determining the pattern of the social order. The findings provide a hint that even when System-critical information is partly accepted, some people may find alternative ways of justifying the way things are. The complex psychology of status quo orientations would thus appear to merit greater research attention. Jost et al. (2004) proposed that system justification involves both psychological and social needs to perceive the current state of affairs as legitimate, natural and fair. The study that we report suggests that even where a lack of fairness is conceded, belief in some natural order underpinning the status quo may serve to maintain a perception of some sort of stability, if not legitimacy.

Notes

Banfield et al. (2011) suggest that the GSJ scale could be employed as more than merely a dependent variable. They use it as an individual difference measure to assess a person’s level of system justification. Similarly, we employed GSJ as an individual difference measure prior to exposure to the manipulation text so as to differentiate between people that are higher versus lower in general system justification.

References

Banfield, J. C., Kay, A. C., Cutright, K. M., Wu, E. C., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2011). A person by situation account of motivated system defense. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 212–219.

Brandt, M. (2013). Do the disadvantaged legitimize the social system? A large-scale test of the status–legitimacy hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 765–785.

Carrington, D. (2015). Fossil fuels subsidised by $10 m a minute, says IMF. Retrieved August 3, 2015 from the Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/may/18/fossil-fuel-companies-getting-10m-a-minute-in-subsidies-says-imf.

Clark, B., & York, R. (2005). Carbon metabolism: Global capitalism, climate change, and the biospheric rift. Theory and Society, 34, 391–428.

Dunlap, R. E. (2013). Climate change skepticism and denial: An introduction. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 691–698.

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. (2008). A widening gap: Republican and democratic views on climate change. Environment, 50, 26–35.

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2011). Organized climate change denial. In J. S. Dryzek, R. B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 144–160). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feygina, I. (2013). Social justice and the human–environment relationship: Common systemic, ideological, and psychological roots and processes. Social Justice Research, 26, 363–381.

Feygina, I., Jost, J. T., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2010). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of ‘system-sanctioned change’. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 326–338.

Friedman, R., & Sutton, B. (2013). Selling the war? System-justifying effects of commercial advertising on civilian casualty tolerance. Political Psychology, 34, 351–367.

Gladwin, T. N., Newburry, W. E., & Reiskin, E. D. (1997). Why is the northern elite mind biased against community, the environment, and a sustainable future? In M. H. Bazerman, D. M. Messick, A. E. Tenbrunsel, & K. A. Wade-Benzioni (Eds.), Environment, ethics, and behavior. San Francisco: The New Lexington Press.

Hennes, E., Nam, H., Stern, C., & Jost, J. (2012). Not all ideologies are created equal: Epistemic, existential, and relational needs predict system-justifying attitudes. Social Cognition, 30, 669–688.

IPCC. (2013). Summary for policymakers. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, M. (1991). The green economy: Environment, sustainable development, and the politics of the future. London: Pluto Press.

Johnson, I. R., & Fujita, K. (2012). Change we can believe in: Using perceptions of changeability to promote system-change motives over system-justification motives in information search. Psychological Science, 23, 133–140.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25, 881–919.

Jost, J. T., Gaucher, D., & Stern, C. (2015). “The world isn’t fair”: A system justification perspective on social stratification and inequality. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 2: Group processes (pp. 317–340). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003a). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of system justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 260–265.

Jost, J., Nosek, B., & Gosling, S. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 126–136.

Jost, J. T., Pelham, B. W., Sheldon, O., & Sullivan, B. N. (2003b). Social inequality and the reduction of ideological dissonance on behalf of the system: Evidence of enhanced system justification among the disadvantaged. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 13–36.

Jost, J. T., & Thompson, E. P. (2000). Group-based dominance and opposition to equality as independent predictors of self-esteem, ethnocentrism, and social policy attitudes among African Americans and European Americans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 209–232.

Kasser, T., Cohn, S., Kanner, A., & Ryan, R. (2007). Some costs of American corporate capitalism: A psychological exploration of value and goal conflicts. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 1–22.

Kay, A. C., & Friesen, J. (2011). On social stability and social change: Understanding when system justification does and does not occur. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 360–364.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Peach, J. M., Laurin, K., Friesen, J., Zanna, M. P., et al. (2009). Inequality, discrimination, and the power of the status quo: Direct evidence for a motivation to see the way things are as the way they should be. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 421–434.

Kay, A. C., & Jost, J. T. (2003). Complementary justice: Effects of “poor but happy” and “poor but honest” stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 823–837.

Klein, N. (2014). This changes everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C. & Smith, N. (2011). Global warming’s six Americas. New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, Yale University and George Mason University.

Magdoff, F. & Foster, J. B. (2010). What every environmentalist needs to know about capitalism. Retrieved August 3, 2015 from Monthly Review http://monthlyreview.org/2010/03/01/what-every-environmentalist-needs-to-know-about-capitalism.

Martorana, P. V., Galinsky, A. D., & Rao, H. (2005). From system justification to system condemnation: Antecedents of attempts to change power hierarchies. Research on Managing Groups and Teams, 7, 285–315.

McCright, A., & Dunlap, R. (2011a). Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change, 21, 1163–1172.

McCright, A., & Dunlap, R. (2011b). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociological Quarterly, 52, 155–194.

Meehl, G. A., Washington, W. M., Collins, W. D., Arblaster, J. M., Hu, A., Buja, L. E., et al. (2005). How much more global warming and sea level rise? Science, 307, 1769–1772.

Mehrabian, A. (1996). Relations among political attitudes, personality, and psychopathology assessed with new measures of libertarianism and conservatism. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 469–491.

Merchant, C. (2005). Radical ecology: The search for a livable world. New York: Routledge.

Monbiot, G. (2006). The denial industry. Retrieved August 3, 2015 from the Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/sep/19/ethicalliving.g2.

Newell, P. (2012). Globalization and the environment: Capitalism, ecology and power. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in denial. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. (2010). Defeating the merchants of doubt. Nature, 465, 686–687.

Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2003). Public perceptions of risk, science and governance: Main findings of a British survey of five risk cases. Norwich: University of East Anglia and MORI.

Shepherd, S., & Kay, A. (2012). On the perpetuation of ignorance: System dependence, system justification, and the motivated avoidance of sociopolitical information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 264–280.

Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environmental Planning A, 42, 1273–1285.

Sparks, P., Jessop, D., Chapman, J., & Holmes, K. (2010). Pro-environmental actions, climate change, and defensiveness: Do self-affirmations make a difference to people’s motives and beliefs about making a difference? British Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 553–568.

van der Toorn, J., Nail, P., Liviatan, I., & Jost, J. (2014). My country, right or wrong: Does activating system justification motivation eliminate the liberal-conservative gap in patriotism? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 50–60.

Wakslak, C., Jost, J., & Bauer, P. (2011). Spreading rationalization: Increased support for large-scale and small-scale social systems following system threat. Social Cognition, 29, 288–302.

Webb, J. (2012). Climate change and society: The chimera of behaviour change technologies. Sociology, 46, 109–125.

Yoshimura, K., & Hardin, C. (2009). Cognitive salience of subjugation and the ideological justification of U.S. geopolitical dominance in Japan. Social Justice Research, 22, 298–311.

Zimmerman, J., & Reyna, C. (2013). The meaning and role of ideology in system justification and resistance for high- and low-status people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 1–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, S., Sparks, P. Neither Fair nor Unchangeable But Part of the Natural Order: Orientations Towards Inequality in the Face of Criticism of the Economic System. Soc Just Res 29, 456–474 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-016-0270-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-016-0270-1