Abstract

This paper analyses the dynamics of poverty in Italy and compares it with that in France, Spain and the UK. For this purpose, we use transition matrices of entry and exit poverty rates and quantify true state dependence through econometric techniques. The analysis exploits the longitudinal component of EU-SILC for the period 2009–2012. Estimation of dynamic random effects probit models shows that, in all countries, after controlling for individual heterogeneity and initial conditions, there is evidence of true state dependence. In comparative terms, when not accounting for regional disparities within countries, the degree of poverty persistence is highest in Italy and lowest in the UK. If regional effects are considered, the degree of poverty persistence in Italy is of the same order of magnitude as in France and Spain, but higher than in the UK. Our findings suggest that unlike other countries, in Italy regional disparities play an important role in explaining poverty state dependence.

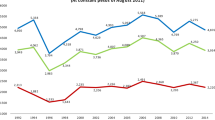

Source: Eurostat

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the EU-27 the current poverty rate ranged between 16.6% in 2008 and 16.8% in 2011, of which 51.8% and 60.1% respectively were persistently poor, showing an increasing trend across the crisis years.

Andriopoulou and Tsakloglou (2011) provide a similar analysis based on European Community Household Panel (ECHP) data for the period 1994–2000.

Authors’ calculations on Eurostat regional data.

Source: own calculations on longitudinal EU-SILC 2009–2012.

For details on the data see Eurostat (2013). The version of the dataset is “EU-SILC Longitudinal UDB 2012—version 1 of August 2014”, the latest provided via our contract with Eurostat. It does not contain data on Germany or Sweden, two countries often used as benchmarks in international comparisons. Our selection of countries is based on the availability of the explanatory variables in the econometric analysis, e.g. Portugal and the Netherlands are excluded due to lack of data at NUTS level.

We drop individuals with missing variables for the whole period.

Disposable income is measured as the sum of net earnings from work, including company cars, social benefits received in cash, income from investment and property and inter-household payments, but excludes non-monetary income components such as imputed rents, the value of goods produced for own consumption and non-cash employee income (with the exception of company cars). The equivalence scale used is the modified OECD scale which assigns the value 1 to the first adult, 0.5 to each other adult and 0.3 to each child under the age of 14. Eurostat directives on poverty and social exclusion advise using the poverty line computed on cross-sectional data when conducting poverty analysis on the longitudinal dataset.

A similar analysis is provided for Turkey in Demir Seker and Dayioglu (2015).

Both the Heckman and the Hyslop models rely on some strong assumptions, such as normality of the error term and zero-correlation between unobserved heterogeneity and the covariates. We are aware of the limits of our analysis and therefore suggest some caution in interpreting our results.

Low education = pre-primary, primary or lower secondary; Intermediate education = higher secondary, post-secondary non tertiary; High education: tertiary education.

In our selection of countries, the information on ‘chronic illness’ has no significant effect on determining poverty in the initial conditions. For this reason, we use the variable 'having limitation in activities due to health problems' as a proxy.

In 2012, the proportion of people in the EU at risk of poverty or social exclusion was 27% among those living in rural areas, 24.8% among those living in cities and 22.5% among those living in towns and suburbs. Source: Eurostat, People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by degree of urbanization [ilcpeps_13].

The best option would be to use pre-sample information as the determinant of the initial conditions, but only a few studies, such as Cappellari and Jenkins (2004) and Stewart (2007), do this. These works use as IVs respondent’s parental background. Among those studies lacking pre-sample information in their data, to our knowledge, the only work using the same methodology as ours and providing a comprehensive discussion of the chosen instruments, is Ayllón (2013). Other related works, such as Poggi (2007), Biewen (2009), Devicienti and Poggi (2011), apply Wooldridge’s (2005) method and do not use IVs as such, but instead employ the initial value of the regressors and their time-means. In our case this methodology cannot be implemented because of the short longitudinal component of our data (3 or 4 years). Another paper that does not use exogenous instruments in the initial condition equations is Alessie et al. (2004).

To test the validity of our instruments, in addition to our setting with exclusion restrictions we estimated the Heckman and Hyslop models in a setting without exclusion restrictions, that is including the IVs in the structural equation as well. We compared the confidence interval of the lagged dependent variable ‘being poor at time t-1’ in the two settings (as in Poggi 2007): in all cases and in all countries, the confidence intervals overlap, providing evidence that the exclusion restrictions do not significantly affect the estimates of our parameter of interest (“Appendix” Table 11).

To compute the APE, we follow Wooldridge (2005) and Stewart (2007), based on estimates of counterfactual outcome probabilities taking the lagged dependent variable \(y_{t - 1}\) of Eq. (1), i.e., being poor at time t-1, as fixed at 0 (\(\hat{p}_{0}\)) and at 1 (\(\hat{p}_{1}\)). The APE corresponds to the average of the differences between the two counterfactual probabilities (\(\hat{p}_{1} - \hat{p}_{0}\)) of each individual in the sample.

Authors’ calculations on Eurostat regional data.

In the same period, all European countries experienced a reduction in geographical disparities. For instance, between 1955 and 1977, the proportions of the population living in regions whose per capita output was at least 15% below the national average halved in France and Spain and nearly evened out in the UK (Iuzzolino et al. 2011).

The growth effect captures how much the poverty risk would change over a given period of time had the income distribution not changed; the inequality effect captures by how much the poverty risk would change had the average income not changed.

Estimated coefficients of the initial conditions equation are reported in “Appendix” Table 13. The likelihood ratio test does not reject the joint significance of the instruments at conventional confidence levels.

Given the counter-intuitive direction of the effect of being female, we tried to disentangle this effect by estimating a specification in which ‘being female’ is interacted with ‘living in a household in which the head is male’. In this case, at least of Italy, the sign of the newly introduced variable is positive, suggesting that the negative sign of ‘being female’ may depend on the fact that females are exposed to a lower poverty risk because they live in households with a male head. In Spain the coefficient of ‘being female’ interacted with ‘living in a household in which the head is male’ remains negative.

The non-employment dummy includes both unemployed and inactive. This choice is motivated by the small sample size of these two categories.

We suspected that this result might depend on the number of NUTS-1 regions in Italy being only 5, compared to 8 in France, 7 in Spain and 12 in the UK. This implies a larger population size of Italian regions compared to that of regions of other countries. As a robustness check, we re-estimated the models for France, Spain and the UK, increasing the level of aggregation of the regional dummies or, in other words, creating larger regions according to their geographical location (e.g. north-east and north-west combined into North, etc.). The results were robust to these changes.

References

Aassve, A., Burgess, S. M., Dickson, M., & Propper, C. (2006). Modelling poverty by not modelling poverty: An application of a simultaneous hazards approach to the UK. LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASE106.

Andriopoulou, E., & Tsakloglou, P. (2011). The determinants of poverty transitions in Europe and the role of duration dependence, IZA DP No. 5692.

Arranz, J. M., & Cantó, O. (2012). Measuring the effect of spell recurrence on poverty dynamics—Evidence from Spain. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 10(2), 191–217.

Arulampalam, W., & Stewart, M. B. (2009). Simplified implementation of the Heckman estimator of the dynamic probit model and a comparison with alternative estimators. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 71(5), 659–681.

Ayllón, S. (2013). Understanding poverty persistence in Spain. SERIEs - Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 4(2), 201–233.

Ayllón, S. (2015). Youth poverty, employment, and leaving the parental home in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(4), 651–676.

Ayllón, S., & Gabos, A. (2016). The interrelationships between the Europe 2020 poverty and social exclusion indicators. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1212-2.

Baldini, M., & Ciani, E. (2011). Inequality and poverty during the recession in Italy. Politica Economica-Journal of Economic Policy (PEJEP), 27(3), 297–322.

Bane, M. J., & Ellwood, D. T. (1986). Slipping into and out of poverty: The dynamics of spells. The Journal of Human Resources, 21(1), 1–23.

Biewen, M. (2006). Who are the chronic poor? An econometric analysis of chronic poverty in Germany. Research on Economic Inequality, 13(1), 31–62.

Biewen, M. (2009). Measuring state dependence in individual poverty histories when there is feedback to employment status and household composition. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24(7), 1095–1116.

Biewen, M. (2014). Poverty persistence and poverty dynamics. IZA World of Labor, 2014, 103. doi:10.15185/izawol.103.

Biewen, M., & Jenkins, S. P. (2005). Accounting for differences in poverty between the USA, Britain and Germany. Empirical Economics, 30(2), 331–358.

Burgess, S., & Propper, C. (1998). An economic model of household income dynamics, with an application to poverty dynamics among American women. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics, London. CASE9.

Cantó-Sánchez, O. (1996). Poverty dynamics in Spain: A study of transitions in the 1990s. STICERD—Distributional Analysis Research Programme Papers 15, Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines, LSE.

Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2004). Modelling low income transitions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 19(5), 593–610.

Coppola, L., & Di Laurea, D. (2014). Persistent at-risk-of-poverty rate in Italy (2007–2010). ISTAT, wp 3.

D’Ambrosio, C., Deutsch, J., & Silber, J. (2011). Multidimensional approaches to poverty measurement: An empirical analysis of poverty in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, based on the European panel. Applied Economics, 43(8), 951–961.

Damioli, G. (2010). How and why dynamics of poverty differ across European countries. Presented at 31st general conference of the international association for research in income and wealth, St. Gallen, Switzerland. http://www.iariw.org/papers/2010/6dDamioli.pdf.

Demir Şeker, S., & Dayıoğlu, M. (2015). Poverty dynamics in Turkey. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(3), 477–493.

Demir Şeker, S., & Jenkins, S. P. (2015). Poverty trends in Turkey. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 13, 401–424.

Devicienti, F. (2002). Poverty persistence in Britain: A multivariate analysis using the BHPS, 1991–1997. Journal of Economics, 77(1), 307–340.

Devicienti, F., Gualtieri, V., & Rossi, M. (2014). The persistence of income poverty and lifestyle deprivation: Evidence from Italy. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(3), 246–278.

Devicienti, F., & Poggi, A. (2011). Poverty and social exclusion: Two sides of the same coin or dynamically interrelated processes? Applied Economics, 43(25), 3549–3571.

Dickens, R., & Ellwood, D. T. (2001). Whither poverty in Great Britain and the United States? The determinants of changing poverty and whether work will work. NBER Working Paper No. 8253.

Duiella, M., & Turrini, A. (2014). Poverty developments in the EU after the crisis: A look at main drivers. ECFIN Economic Brief, Issue 31, May.

Duncan, G. J. (1983). The implications of family composition for the dynamic analysis of family economic well-being. In A. B. Atkinson & F. A. Cowell (Eds.), Panel data on incomes. London: Occasional Paper No. 2, ICERD, London School of Economics.

Duncan, G. J., Gustafsson, B., Hauser, R., Schmauss, G., Messinger, H., Muffels, R., et al. (1993). Poverty dynamics in eight countries. Journal of Population Economics, 6, 234–295.

Duncan, G. J., & Rodgers, W. (1991). Has child poverty become more persistent? American Sociological Review, 56, 1007–1021.

Eiffe, F. F., & Till, M. (2013). The longitudinal component of EU-SILC: Still underused? Net-SILC2 Working Paper, 1, 2013.

Eurostat. (2013). Description of target variables: Cross-sectional and longitudinal. 2012 operation (version May 2013). Eurostat. Directorate F: Social and information society statistics. Unit F-4: Quality of life.

Finnie, R. (2000). Low income (poverty) dynamics in Canada: Entry, exit, spell durations, and total time. Working paper No. W-00-7E, Applied Research Branch, Strategic Policy, Human Resources Development Canada, Hull, Quebec.

Fouarge, D., & Layte, R. (2005). Welfare regimes and poverty dynamics: The duration and recurrence of poverty spells in Europe. Journal of Social Policy, 34(3), 407–426.

Giarda, E. (2013). Persistency of financial distress amongst Italian households: Evidence from dynamic models for binary panel data. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37, 3425–3434.

Hansen, J., & Wahlberg, R. (2004). Poverty persistence in Sweden. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1209.

Heckman, J. J. (1981). Statistical models for discrete panel data. In C. F. Manski & D. McFadden (Eds.), Structural analysis of discrete data with econometric applications (pp. 114–178). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hyslop, D. R. (1999). State dependence, serial correlation and heterogeneity in intertemporal labor force participation of married women. Econometrica, 67(6), 1255–1294.

Iuzzolino, G., Pellegrini, G., & Viesti, G. (2011). Convergence among Italian Regions, 1861–2011. Economic History Working Papers, 22, Bank of Italy, Rome.

Jarvis, S., & Jenkins, S. P. (1997). Low income dynamics in 1990s Britain. Fiscal Studies, 18, 123–142.

Jenkins, S. P. (2000). Modelling household income dynamics. Journal of Population Economics, 13, 529–567.

Jenkins, S. P., Rigg, J. A., & Devicienti, F. (2001). The dynamics of poverty in Britain. Department of Work and Pensions Report No. 187, Corporate Document Services, Leeds.

Jenkins, S. P., & Van Kerm, P. (2014). The relationship between EU indicators of persistent and current poverty. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 611–638.

Lillard, L. A., & Willis, R. J. (1978). Dynamic aspects of earning mobility. Econometrica, 46(5), 985–1012.

Lucchetti, R., & Pigini, C. (2017). DPB: dynamic panel binary data models in gretl. Journal of Statistical Software. (in press)

Poggi, A. (2007). Does persistence of social exclusion exist in Spain? The Journal of Economic Inequality, 5, 53–72.

Polin, V., & Raitano, M. (2012). Poverty dynamics in clusters of European Union countries: Related events and main determinants. Working Paper Series Department of Economics, University of Verona, wp no. 10.

Stevens, A. H. (1994). The dynamics of poverty spells: Updating Bane and Ellwood. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 34–37.

Stevens, A. H. (1999). Climbing out of poverty, falling back in: Measuring the persistence of poverty over multiple spells. Journal of Human Resources, 34(3), 557–588.

Stewart, M. B. (2006a). -redprob- A Stata program for the Heckman estimator of the random effects dynamic probit model. http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/academic/stewart/stata/redprobnote.pdf.

Stewart, M. B. (2006b). Maximum simulated likelihood estimation of random effects dynamic probit models with autocorrelated errors. The Stata Journal, 6(2), 256–272.

Stewart, M. B. (2007). The interrelated dynamics of unemployment and low-wage employment. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(3), 511–531.

Van Kerm, P., & Pi Alperin, M. (2010). Inequality, growth and mobility: The inter-temporal distribution of income in European countries 2003–2007. Eurostat, Methodologies and Working papers.

Vecchi, G. (2011). In ricchezza e in povertà. Il benessere degli italiani dall’Unità a oggi. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Wilde, J. (2000). Identification of multiple equation probit models with endogenous dummy regressors. Economics Letters, 69, 309–312.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2005). Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem in dynamic, nonlinear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(1), 39–54.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was begun in 2014 when Gloria Moroni started an internship at Prometeia. We would like to thank Marianna Brunetti, Giovanni Iuzzolino, Riccardo “Jack” Lucchetti, Claudia Pigini, Livia Simongini, Costanza Torricelli, Luca Zanin and participants at seminars at the University of Ancona and the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia for useful suggestions. The comments of two anonymous referees are also gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of the affiliated institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giarda, E., Moroni, G. The Degree of Poverty Persistence and the Role of Regional Disparities in Italy in Comparison with France, Spain and the UK. Soc Indic Res 136, 163–202 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1547-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1547-3