Abstract

The recognition of poverty as a multidimensional concept has led to the development of more adequate tools for its identification. By allowing for subgroup and regional decompositions, those instruments are useful to allocate public action where most needed. This paper applies the Alkire and Foster (2011a) Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) to study single-mother and biparental families in Nicaragua, modifying its original structure to match more closely with the country’s current structural problems. Using Nicaragua’s last Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2011/2012), our multidimensional poverty figures contrast with the government’s national poverty line estimates, suggesting that income poverty overestimates the number of poor people. Thus, our MPI can help as a complement for traditional consumption poverty and Basic Needs analysis; even extending the exploration by using other official household surveys. On the other hand, multidimensional poverty analysis found poverty dominance of male-headed families over single-mother and female-headed biparental families, which serves to contradict the notion of women being more vulnerable than men. Within the MPI, the most important contributor was the Living Standards dimension, composed by indicators directly related to housing conditions, and the second most deprived dimension was Education. A strong policy implication that arises from our findings is the reduction of the urban–rural poverty gap. Specifically, our findings exalt the need for governmental policies directed to reduce Nicaragua’s housing and educational deficits as a priority, particularly in rural areas.

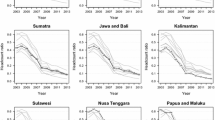

Source: based on data from ENDESA 2011/2012

Source: based on data from ENDESA 2011/2012

Source: based on data from ENDESA 2011/2012

Source: based on data from ENDESA 2011/2012

Source: based on data from ENDESA 2011/2012

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Arends-kuenning and Moylan (2012) estimated this figure in 76 % with data from previous ENDESA (2006/2007).

According to the 2014 Global Gender Gap Report (Hausmann et al. 2014), Nicaragua reached sixth place as one of the best countries in the world in terms of gender equity, only behind Iceland, Finland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden.

See Alkire and Santos (2014) for an application of the Global MPI to over 100 developing countries.

On this matter, Dewilde (2008) observes that between-country differences for multidimensional poverty in Europe can be explained by country-specific arrangements on welfare policies.

The 5DE sub-index has a weight of 90 %, with the other 10 % consisting of a Gender Parity Index (GPI).

According to the Bouillon et al. (2012), 78 % of households in Nicaragua have sub-standard housing (the highest rate for Latin America and the Caribbean). The estimated housing deficit rounds 957,000 units, with 348,000 corresponding to the need for new houses and 609,000 for improvement of existing units. Furthermore, there is evidence for a positive relationship between ‘happiness’ and house ownership in Latin America (Ruprah 2010). Considered an important issue in the region, Santos et al. (2015) included housing tenure as a relevant component in their MPI for Latin American countries.

According to government calculations, those subsidies benefit approximately 2.5 million people on a daily basis (Consejo de Comunicación y Ciudadanía 2011). Additionally, data from EMNV 2009 reveals that transport expenditures represent only 3.0 and 2.6 % of total annual per capita expenditures for the poor and extremely poor respectively (INIDE 2011).

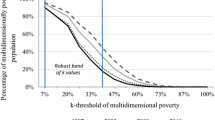

In our index, that percentage translates to a deprivation cutoff of four or more indicators.

The final sample size is 86.5 and 87.0 % of the original survey sample for single mother and biparental households respectively.

Table 7 in the Appendix expands these and other socio-demographic informations.

First-level administrative and political subdivisions in Nicaragua (departamentos).

On this matter, it is useful to know the percentage of self-reported household heads that had a job, as a proxy for economic contribution (Handa 1994). For Nicaragua, work-related information from EMNV 2009 shows that 75.2 % of single mothers had a job, with a higher percentage of “working heads” for male heads (91.0 %) and lower for female heads (64.6 %) in biparental families.

Following that recommendation, Alkire et al. (2013) compared dual-adult and female-only headed households in their pilot studies.

References

Acock, A. C. (2010). A gentle introduction to Stata (3rd ed.). College Station: Stata Press.

Alaniz, E., Carrión, G., & Gindling, T. H. (2015). Dinámica de las Mujeres Nicaragüenses en el Mercado Laboral. Managua: FIDEG.

Aldaz-Carroll, E., & Morán, R. (2001). Escaping the poverty trap in Latin America: The role of family factors. Cuadernos de Economia, 38(114), 155–190. http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=419960.

Alkire, S., Apablaza, M., & Jung, E. (2014). Multidimensional poverty measurement for EU-SILC countries. OPHI Research in Progress, 3, 66.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2007). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement (No. 7). Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), Oxford Department of International Development.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2009). Counting and multidimensional poverty. In J. Von Braun, R. V. Hill, & R. Pandya-Lorch (Eds.), The poorest and hungry: Assessments, analyses, and actions: An IFPRI 2020 book (1st ed.). Washington, D.C: IFPRI.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011a). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7), 476–487. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011b). Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 289–314. doi:10.1007/s10888-011-9181-4.

Alkire, S., Foster, J. E., Seth, S., Santos, E., Roche, J. M., & Ballon, P. (2015). (Eds.). Chapter 8—Robustness analysis and statistical inference. In Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2010). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. United Nations development programme human development report office background paper (Vol. 11).

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2013). A multidimensional approach: Poverty measurement & beyond. Social Indicators Research, 112, 239–257. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0257-3.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2014). Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Development, 59, 251–274. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.026.

Amnistía Internacional. (2009). La prohibición total del aborto en Nicaragua. La vida y la salud de las mujeres en peligro; los profesionales de la medicina, criminalizados. Madrid.

Arends-Kuenning, M., & Moylan, M. (2012). Pathways into single-motherhood and their implications for Children’s health and education in Nicaragua. In Anual meeting, population association of america (p. 14). San Francisco.

Atkinson, A. B. (2003). Multidimensional deprivation: contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1, 51–65. doi:10.1023/A:1023903525276.

Avendaño, N. (2008). El riesgo social de Nicaragua: políticas sociales y la Cumbre del Milenio. Managua: Consultores para el Desarrollo Empresarial (COPADES). http://books.google.com.br/books?id=oBUoAQAAIAAJ.

Batana, Y. M. (2013). Multidimensional measurement of poverty among women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Social Indicators Research, 112(2), 337–362. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0251-9.

Battiston, D., Cruces, G., Lopez-Calva, L. F., Lugo, M. A., & Santos, M. E. (2013). Income and beyond: Multidimensional poverty in six Latin American countries. Social Indicators Research, 112, 291–314. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0249-3.

Bobonis, G. J. (2009). Is the allocation of resources within the household efficient? New evidence from a randomized experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 117(3), 453–503. doi:10.1086/600076.

Bouillon, C.P., Muñoz Miranda, A., Fretes Cibils, V., Blanco, A.G., Buruchowicz, C., Medellín, N., et al. (2012). Un espacio para el desarrollo: los mercados de vivenda en América Latina y el Caribe. Nueva York: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.

Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1, 25–49. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79253-8.

Bradshaw, S. (2009). An unholy trinity: The church, the state, the banks and the challenges for women mobilising for change in Nicaragua. IDS Bulletin, 39(6), 67–74. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00513.x.

Bradshaw, S., & Quirós, A. (2008). Women beneficiaries or women bearing the cost? A gendered analysis of the red de protección social in Nicaragua. Development and Change, 39(5), 823–844.

Burniaux, J.-M., Dang, T.-T., Fore, D., Förster, M., Mira d’Ercole, M., & Oxley, H. (1998). Income distribution and poverty in selected OECD countries (No. 189). Paris. http://www.oecd.org/tax/public-finance/1864447.pdf.

Buthan. (2012). Buthan multidimensional poverty index. Buthan: National Statistics Bureau. http://www.nsb.gov.bt/publication/files/pub0ll1571bt.pdf.

Buvinic, M., & Gupta, G. R. (1997). Female-headed households and female-maintained families: Are they worth targeting to reduce poverty in developing countries? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 45, 259. doi:10.1086/452273.

Calva, L. F. L., & Juárez, E. O. (2009). Medición multidimensional de la pobreza en México: significancia estadística en la inclusión de dimensiones no monetarias. Estudios Económicos, 1, 3–33.

Castro Martín, T., Cortina, C., García, T., & Pardo, I. (2010). Maternidad sin matrimonio en América Latina: Análisis comparativo a partir de datos censales. Notas de Población, 93, 37–76. http://www.eclac.cl/publicaciones/xml/9/45549/lcg2509-P_2.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2014.

Chakravarty, S. R., Mukherjee, D., & Ranade, R. R. (1998). On the family of subgroup and factor decomposable measures of multidimensional poverty. Research on Economic Inequality, 8, 175–194.

Chant, S. (2003). New contributions to the analysis of poverty: Methodological and conceptual challenges to understanding poverty from a gender perspective. Serie Mujer y Desarrollo (Vol. 47.). Santiago: United Nations Publications.

Chant, S. (2007). Children in female-headed households: Interrogating the concept of an “inter-generational transmission of disadvantage” with particular reference to the Gambia, Philippines and Costa Rica (No. 19). London: New Working Paper Series.

Chant, S. (2008). The “feminisation of poverty” and the “feminisation” of anti-poverty programmes: Room for revision? Journal of Development Studies, 44(2), 165–197. doi:10.1080/00220380701789810.

CONEVAL. (2010). Metodologia para la medición multidimencional de la pobreza en México. México: CONEVAL.

Consejo de Comunicación y Ciudadanía. (2011). Nicaragua triunfa no. 30. Nicaragua triunfa. Managua, Nicaragua: Consejo de Comunicación y Ciudadanía.

Corder, G. W., & Foreman, D. I. (2009). Nonparametric statistics for non-statisticians: A step-by-step approach. Hoboken: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118165881.ch5.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1339. doi:10.1086/511799.

De Franco, M. (2011). Causas del (de) Crecimiento Económico de Largo Plazo de Nicaragua (No. 7). Managua.

Denis, A., Gallegos, F., & Sanhueza, C. (2010). Pobreza multidimensional en Chile: 1990–2009. Documento de Trabajo: ILADES/Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

Dewilde, C. (2008). Individual and institutional determinants of multidimensional poverty: A European comparison. Social Indicators Research, 86(2), 233–256. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9106-6.

Diana Deere, C., Alvarado, G. E., & Twyman, J. (2012). Gender inequality in asset ownership in Latin America: Female owners vs household heads. Development and Change, 43(2), 505–530. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01764.x.

ECLAC. (2004). Roads towards gender equity in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC.

Förster, M. (1994). Measurement of low incomes and poverty in a perspective of international comparisons (No. 14). Paris: OECD.

González de la Rocha, M. (2002). The Urban Family and Poverty in Latin America. In J. Abassi & S. L. Lutjens (Eds.), Rereading women in Latin America and the Caribbean: The political economy of gender (pp. 61–77). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

Granelli, R. (2011). La penalización del aborto en nicaragua. una práctica de feminicidio de estado. Universidad de Granada y Università di Bologna.

Hamilton, L. C. (2006). Statistics with STATA updated for version 9. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Handa, S. (1994). Gender, headship and intrahousehold resource allocation. World Development, 22(10), 1535–1547. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)90036-1.

Handa, S. (1996). Expenditure behavior and children’s welfare: An analysis of female headed households in Jamaica. Journal of Development Economics, 50, 165–187. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(96)00008-9.

Hausmann, R., Tyson, L., Bekhouche, Y., & Zahidi, S. (2014). The global gender gap report 2014. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Herrera, C. (2013). Nicaragua: Violencia hacia la mujer está institucionalizada. Noticias Aliadas. http://www.noticiasaliadas.org/articles.asp?art=6910#. Accessed 28 March 2015.

ICEFI. (2012). La política fiscal de Centroamérica en tiempos de crisis. Ciudad de Guatemala: Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales.

INIDE. (2011). Encuesta de Hogares sobre Medición del Nivel de Vida 2009—Principales Resultados. Managua: Gobierno de Nicaragua.

INIDE. (2013). Encuesta Nicaraguense de Demografía y Salud 2011/2012—Aspectos Metodológicos. Managua.

Levine, S., Muwonge, J., & Batana, Y. M. (2012). A robust multidimensional poverty profile for Uganda (No. 55). Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), Oxford Department of International Development.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0033.

McLanahan, S., & Beck, A. N. (2010). Parental relationships in fragile families. The Future of Children, 20(2), 17–37. doi:10.1353/foc.2010.0007.

McLanahan, S., & Booth, K. (1989). Mother-only families: Problems, prospects, and politics. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(3), 557–580. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/352157. Accessed 11 Dec 2013.

Mendoza, F., & Altamirano, Á. J. (2013). Subempleo laboral en las industrias productivas de Nicaragua. Encuentro, 94, 42–61. http://encuentro.uca.edu.ni/pages/e94-art2.html.

Miklos, A. Z. (2015). Mediated intimacies: State intervention and gender violence in Nicaragua. Encuentro, 100, 6–37. http://encuentro.uca.edu.ni/pdf/e100/e100-art1.pdf.

Montenegro, S. (2014). Nicaragua, el más equitativo en la desigualdad. Confidencial. Managua. http://www.confidencial.com.ni/articulo/19962/nicaragua-el-mas-equitativo-en-la-desigualdad.

Montoya, A. J., de Loreto, M. D. D. S. D., & Damiano, K. M. (2015). O perfil socioeconômico das donas de casa na Nicarágua. Estudos Feministas, 23(1), 53–70.

OECD. (2011). Income and wealth. In How’s life?: Measuring well-being (p. 284). Paris: OECD Publishing. http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/economics/how-s-life/income-and-wealth_9789264121164-4-en#page16.

OPHI. (2011). OPHI country briefing 2011: Nicaragua. Oxford: University of Oxford.

OPHI. (2013). Measuring multidimensional poverty: Insights from around the world. Oxford poverty and human development initiative. Oxford: University of Oxford.

OPHI. (2014). OPHI country briefing 2014: Nicaragua. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Pacheco Medina, E. C. (2013). Gender wage gap in Urban Nicaragua: Evidence from decomposition analysis. Lund: Lund University.

Porta, E., & Laguna, J. R. (2013). Análisis de la Rentabilidad de la Educación en Nicaragua. Managua: FUNIDES.

Ravallion, M. (2011). On multidimensional indices of poverty. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 235–248. doi:10.1007/s10888-011-9173-4.

RIO GROUP. (2006). Compendium of best practices in poverty measurement. Rio de Janeiro. http://www.ibge.gov.br/poverty/pdf/rio_group_compendium.pdf. Accessed 28 March 2012.

RMCV. (2015). Informe anual de femicidio 2014. Managua: Red de Mujeres contra la Violencia.

Robeyns, I. (2005). The capability approach: Atheoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117. doi:10.1080/146498805200034266.

Rodenberg, B. (2004). Gender and poverty reduction new conceptual approaches in international development cooperation (No. 4). Bonn: German Development Institute.

Rodríguez Sumaza, C., & Luengo Rodríguez, T. (2003). Un análisis del concepto de familia monoparental a partir de una investigación sobre núcleos familiares monoparentales. Papers, Revista de Sociología, 69, 59–62.

Rogan, M. (2015). Gender and multidimensional poverty in South Africa: Applying the global multidimensional poverty index (MPI). Social Indicators Research,, 126(3), 1–20.

Ruprah, I. (2010). Does owning your home make you happier? Impact evidence from Latin America. OVE working papers. http://ideas.repec.org/p/idb/ovewps/0210.html.

Santos, M. E., Villatoro, P., Mancero, X., & Gerstenfeld, P. (2015). A multidimensional poverty index for Latin America. OPHI working paper 79. http://www.ophi.org.uk/a-multidimensional-poverty-index-for-latin-america/.

Sen, A. (1999a). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999b). Commodities and capabilities Oxford India paperbacks (2nd ed.). New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.2307/2232999.

Sen, A. (2003). Development as Capability Expansion. In S. Fukuda-Parr, et al. (Eds.), Readings in human development. New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1714428.

The World Bank. (2012). World development indicators. Washington, DC. http://data.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/wdi-2012-ebook.pdf. Accessed 28 March 2015.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. The Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635. doi:10.2307/145670.

Trejos, J. (2008). Características y evolución reciente del mercado de trabajo en América Central. San José.

Tsui, K. Y. (2002). Multidimensional poverty indices. Social Choice and Welfare, 19, 69–93. doi:10.1007/s355-002-8326-3.

UNFPA. (2013). State of world population 2013. Washington: United Nations.

Vijil, A. A. (2014). Políticas públicas que promueven el empoderamiento económico de las mujeres en Nicaragua. Managua: FIDEG.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) for the scholarship granted for his M.Sc. program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8 and Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Altamirano Montoya, Á.J., Teixeira, K.M.D. Multidimensional Poverty in Nicaragua: Are Female-Headed Households Better Off?. Soc Indic Res 132, 1037–1063 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1345-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1345-y