Abstract

Thailand has been a global economic success story, transforming from one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia in the 1960s, to a modern and dynamic nation, and all within the lifetime of the current generation. However, growth has been accompanied by marked increases in economic inequality both at the regional and individual levels. In this context studying how relatively poor people appraise their situation (‘subjective wellbeing’) and how this relates to traditional ‘objective’ measures of wellbeing such as wealth and basic needs is particularly relevant. This paper investigates the relationship between basic needs as defined by the Theory of Human needs (THN, Doyal and Gough 1991), material wealth and happiness. Specifically, we intend to answer the following research question: Are wealth and basic needs indicators always interchangeable when analyzing happiness determinants in low income settings? The paper focuses on seven communities in the South and North-east of Thailand with contrasting levels of access to markets and services. It challenges the common assumption that at low economic levels, wealth or income matter for people’s happiness because they increase satisfaction of basic needs, arguing instead that wealth might contribute to happiness for personal or symbolic reasons, which are not related to the use of goods as basic needs satisfiers. Thus, it suggests that indicators of wealth and basic needs should not be used interchangeably when studying happiness determinants in low income settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Clark (2002: 81–92) for a discussion of several alternative conceptions of the good.

A discussion about the validity of the scales used in happiness studies can be found in Cummins (2003).

An alternative asset index was computed using factor analysis and principal component analysis. Similar results were obtained when these asset indexes were used as determinants of happiness.

Food shortages are especially common in Ban Dong where nearly 60% of the households reported experiencing food shortages during the year before the interview, possibly due to its relative remoteness and the poor quality of the agricultural land.

A one-way ANOVA (F = 19.876 and p < 0.001) shows that there exist differences within the sites and a post-hoc test (Scheffe) shows that Ban Dong (p < 0.001) and Ban Chai Khao (p < 0.05) are respectively the poorest and the richest sites although the latter is not significantly richer than Ban Tha and Ban Tung Nam.

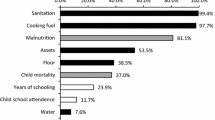

A one-way ANOVA indicates that communities differ in relation to basic needs deprivation levels (F = 13.392 and p < 0.001) and that households in Nai Muang and Ban Chai Khao are significantly better off than people in Ban Thung Nam, Ban Laow and Ban Dong.

Some caution is required when carrying out an empirical analysis of subjective wellbeing using regression analysis due to the small percentage of variation in SWB measures explained by socio-economic-demographic variables (Graham 2005) and the issue of causation (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002). Acknowledging the relevance of the previous debates, we follow the tradition of happiness economics considering that socio-economic variables affect utility which is here approximated by happiness.

In addition to the ordered probit model, a probit model of the selected regression was also estimated. The results were quite similar using both models.

Table 7 in the Appendix contains the description and descriptive statistics of selected variables for the full sample of 745 households.

Age is significant at the 0.05 level and type of job at the 0.10.

Many happiness studies find that the relationship between age and happiness has a U shape implying that there is a turning point at which happiness starts to increase with age (Frey and Stutzer 2002: 54). Although this was also the case in the previous study by Guillen and Velazco (Ibid.) focussing on the rural communities, it was not found when the urban population was added to the sample.

References

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: Satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55, 329–352.

Camfield, L. (2004). Subjective measures of wellbeing for developing countries. In W. Glatzer, S. von Velow, & M. Stoffegren (Eds.), Challenges for the quality of life in contemporary societies (pp. 45–60). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Camfield, L. (2009). Universal coverage but unequal access? Factors affecting the use of health services in Northeast and South Thailand. In V. Møller & D. Huschka (Eds.), Quality of life and the millennium challenge advances in quality-of-life studies, theory and research (pp. 239–264). Netherlands: Springer.

Camfield, L., Choudhury, K., & Devine, J. (2007). Well-being, happiness and why relationships matter: Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 71–91.

Camfield, L., & Guillen-Royo, M. (2010). Wants, needs, satisfactions: A comparative study in Thailand and Bangladesh. Social Indicators Research, 96(2), 183–203.

Camfield, L., & McGregor, J. A. (2005). Resilience and wellbeing in developing countries. In M. Ungar (Ed.), Handbook for working with children and youth: Pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts (pp. 189–210). London: Sage.

Clark, D. A. (2002). Visions of development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Cummins, R. (2003). Normative life satisfaction, measurement issues and a homeostatic model. Social Indicators Research, 64, 225–256.

Desai, M., & Shah, A. (1988). An econometric approach to the measurement of poverty. Oxford Economic Papers, 40(3), 505–522.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective wellbeing? Social Indicators Research, 57, 119–169.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: relative standards, need fulfillment, culture, and evaluation theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 41–78.

Doyal, L., & Gough, I. (1991). A theory of human need. London: Macmillan.

Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & W. R. Melvin (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2004). Global judgments of subjective wellbeing: situational variability and long-term stability. Social Indicators Research, 65, 245–277.

Fafchamps, M., & Shilpi, F. (2006). Subjective welfare, isolation and relative consumption. CEPR Discussion Paper 6002 Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=976748.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frey, B. S. (2008). Happiness. A revolution in economics. London: The MIT Press.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gasper, D. (2004). Subjective and objective wellbeing in relation to economic inputs: puzzles and responses. WeD Working paper 09, University of Bath.

Gasper, D. (2005). Subjective and objective well-being in relation to economic inputs: Puzzles and responses. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 177–206.

Gough, I. (2005). Human wellbeing and social structures. Global Social Policy, 4(3), 289–311.

Graham, C. (2005). Some insights on development from the economics of happiness. World Bank Research Observer, 20, 201–231.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America’. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4(1), 107–122.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Happiness and hardship. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Guillen-Royo, M. (2007). Consumption and wellbeing: motives for consumption and needs satisfiers in Peru. Thesis (PhD), University of Bath, Bath (UK).

Guillen-Royo, M. (2010). Reference group consumption and the subjective wellbeing of the poor in Peru, Journal of Economic Psychology (in press).

Guillen-Royo, M., & Velazco, J. (2006). Exploring the relationship between happiness, objective and subjective wellbeing: evidence from rural Thailand. WeD Working paper 11, University of Bath.

Hirata, J. (2001). Happiness and economics. Thesis (Msc.), Maastricht University, Maastricht.

Isaacs, B. A. (2009). Imagining Thailand in European hypermarkets: New class-based consumption in Chiang Mai’s ‘Cruise ships. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 10(4), 348–363.

Jongudomkarn, D., & Camfield, L. (2005). Exploring the quality of life of people in North Eastern and Southern Thailand. Social Indicators Research, 78, 489–530.

Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2007). Community, comparisons and subjective well-being in a divided society. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organisation, 64, 69–90.

Lelkes, O. (2005). Knowing what is good for you: Empirical analysis of personal preferences and the ‘objective good’. CASE paper no. 94, London School of Economics.

McGregor, A., McKay, A., & Velazco, J. (2007). Needs and resources in the investigation of wellbeing in developing countries: Evidence from Bangladesh and Peru. Journal of Economic Methodology, 14(1), 107–131.

Mills, M. B. (1997). Contesting the margins of modernity: Women, migration, and consumption in Thailand. American Ethnologist, 24, 37–61.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parnwell, M. J. G., & Arghiros, D. A. (1996). Introduction: Uneven development in Thailand. In M. J. G. Parnwell (Ed.), Uneven development in Thailand (pp. 1–27). Aldershot: Avebury Press.

Rojas, M. (2006). Wellbeing and the complexity of poverty: A subjective wellbeing approach. In M. McGillivray & M. Clarke (Eds.), Understanding human wellbeing. New York: United Nations University Press.

Rojas, M. (2007). The complexity of wellbeing. A life-satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In I. Gough & A. McGregor (Eds.), Wellbeing in developing countries. New approaches and research strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rojas, M. (2008). Relative income and well-being in Latin America. Report for the Inter-American Development Bank.

Sahn, D., & Stifel, D. (2003). Exploring alternative measures of welfare in the absence of expenditure data. Review of Income and Wealth, 49(4), 463–489.

Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Ahadi, S. (2002). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: Integrating process models of life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 582–593.

Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Online first publication, June 20 2011. doi:10.1037/a0023779.

UNDP. (2007). Thailand human development report 2007: Sufficiency economy and human development. Bangkok: UNDP.

UNDP. (2010). Thailand human development report 2009: Human security, today and tomorrow. Bangkok: UNDP.

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2007). Happiness in hardship. In L. P. Bruni & P. L. Porta (Eds.), Economics and happiness (pp. 243–266). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Verbeek, M. (2000). A guide to modern econometrics. New York: Wiley.

Warr, P. (2005). Boom, bust and beyond. London: Routledge.

Wellbeing in Developing Countries ESRC Research Group. (2007). The Thai communities and their context. Internal document.

Woodcock, A., Camfield, L., McGregor, J. A., & Martin, F. (2008). Validation of the WeDQoL-Goals-Thailand measure: culture-specific individualised quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 94(1), 135–171.

Acknowledgments

The data analysed in this paper was collected by the UK Economic and Social Research Council research group on Wellbeing in Developing Countries (WeD, www.well-dev.org.uk) as part of its exploration of the social and cultural construction of wellbeing in Thailand. The authors would like to thank our collaborators in Prince of Songkhla and Khon Kaen Universities. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guillen-Royo, M., Velazco, J. & Camfield, L. Basic Needs and Wealth as Independent Determinants of Happiness: An Illustration from Thailand. Soc Indic Res 110, 517–536 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9941-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9941-3