Abstract

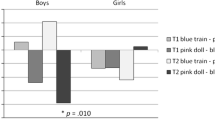

Play with Barbie dolls is an understudied source of gendered socialization that may convey a sexualized adult world to young girls. Early exposure to sexualized images may have unintended consequences in the form of perceived limitations on future selves. We investigated perceptions of careers girls felt they could do in the future as compared to the number of careers they felt boys could do as a function of condition (playing with a Barbie or Mrs. Potato Head doll) and type of career (male dominated or female dominated) in a sample of 37 U.S. girls aged 4–7 years old residing in the Pacific Northwest. After a randomly assigned 5-min exposure to condition, children were asked how many of ten different occupations they themselves could do in the future and how many of those occupations a boy could do. Data were analyzed with a 2 × 2 × 2 mixed factorial ANOVA. Averaged across condition, girls reported that boys could do significantly more occupations than they could themselves, especially when considering male-dominated careers. In addition, girls’ ideas about careers for themselves compared to careers for boys interacted with condition, such that girls who played with Barbie indicated that they had fewer future career options than boys, whereas girls who played with Mrs. Potato Head reported a smaller difference between future possible careers for themselves as compared to boys. Results support predictions from gender socialization and objectification theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Civil Liberties Union. (2013). Title IX-Gender equity in education. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/title-ix-gender-equity-education.

American Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA Task Force on the sexualization of girls. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf.

Archer, L., Dewitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., & Wong, B. (2012). “Balancing acts”: Elementary school girls’ negotiations of femininity, achievement, and science. Science Education, 96, 967–989. doi:10.1002/scd.20131.

Bannon, L. (1998). Mattel, Inc. plans to double sales abroad. Dow Jones Online News from Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.knowledgespace.com.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354–364. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354.

Bronstein, P. (2006). The family environment: Where gender role socialization begins. In J. Worell & C. D. Goodheart (Eds.), The handbook of girls’ and women’s psychological health: Gender and well-being across the lifespan (pp. 262–271). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1017/S003329170621807.

Brownell, K. D., & Napolitano, M. A. (1995). Distorting reality for children: Body size proportions of Barbie and Ken dolls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18, 295–298. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199511)18:3<295::AID-EAT2260180313>3.0.CO;2-R.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Labor force statistics from the current population survey. U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat09.htm.

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of gender development and functioning. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (2nd ed., pp. 92–119). New York: Guilford Press.

Calogero, R. M., Tantleff-Dunn, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2011). Future directions for research and practice. In R. M. Calogero, S. Tantlef-Dunn, & J. K. Thompson (Eds.), Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions (pp. 217–237). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/12304-000.

Coy, M. (2009). Milkshakes, lady lumps and growing up to want boobies: How the sexualisation of popular culture limits girls’ horizons. Child Abuse Review, 18, 372–383. doi:10.1002/car.1094.

Darke, K., Clewell, B., & Sevo, R. (2002). Meeting the challenge: The impact of the National Science Foundation's program for women and girls. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 8, 285–303.

Davison, K. K., Markey, C. N., & Birch, L. L. (2000). Etiology of body dissatisfaction and weight concerns among 5-year-old girls. Appetite, 35, 43–151. doi:10.1006/appe.2000.0349.

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5–8 year old girls. Developmental Psychology, 42, 283–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283.

Dohnt, H., & Tiggemann, M. (2006a). The contribution of peer and media influences to the development of body satisfaction and self-esteem in young girls: A prospective study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 929–936. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.929.

Dohnt, H., & Tiggemann, M. (2006b). Body image concerns in young girls: The role of peers and media prior to adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 141–151. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9020-7.

Durkin, S. J., & Paxton, S. J. (2002). Predictors of vulnerability to reduced body image satisfaction and psychological well-being in response to exposure to idealized female media images in adolescent girls. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 995–1005. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00489-0.

Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R. E., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64, 830–847. doi:10.2307/1131221.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T.-A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.269.

Goodin, S. M., Van Denberg, A., Murnen, S. K., & Smolak, L. (2011). “Putting on” sexiness: A content analysis of the presence of sexualizing characteristics in girls’ clothing. Sex Roles, 65, 1–12. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9966-8.

Gould, M. (2008, October 3). Girls choosing camera lenses over microscopes. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2008/oct/03/science.choosingadegree.

Grabe, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2009). Body objectification, MTV, and psychological outcomes among female adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 2840–2858. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00552.x.

Grabe, S., Hyde, J. S., & Lindberg, S. M. (2007). Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 164–175. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9703-8.

Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460–4786. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460.

Graff, K., Murnen, S. K., & Smolak, L. (2012). Too sexualized to be taken seriously? Perceptions of a girl in childlike vs. sexualizing clothing. Sex Roles, 66, 764–775. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0145-3.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Harter, S. (2003). The development of self-representations during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of Self and Identity (pp. 610–642). New York: Guilford Press.

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional , and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505–570). Hoboken: Wiley.

Hatton, E., & Trautner, M. N. (2011). Equal opportunity objectification? The sexualization of men and women on the cover of Rolling Stone. Sexuality and Culture, 15, 255–278. doi:10.1007/s12119-011-9093-2.

Hebl, M., King, E. B., & Lin, J. (2004). The swimsuit becomes us all: Ethnicity, gender, and vulnerability to self-objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1322–1331. doi:10.1177/0146167204264052.

Huston, A. C. (1983). Sex-typing. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (4th ed., Vol. 4, pp. 387–467). New York: Wiley.

International Labour Organization. (2013). Gender and employment. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/employment/areas/gender-and-employment/lang–en/index.htm.

Kuther, T. L., & McDonald, E. (2004). Early adolescents’ experiences with, and views of, Barbie. Adolescence, 39, 39–51.

Lytton, H., & Romney, D. M. (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 267–296. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.267.

Mattel. (2009). Barbie I can be careers with Richard Dickson [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71d9-tCdCCc.

Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Morry, M. M., & Staska, S. L. (2001). Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33, 269–279. doi:10.1037/h0087148.

Pedersen, E. L., & Markee, N. L. (1991). Fashion dolls: Representations of ideals of beauty. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 73, 93–94. doi:10.2466/pms.1991.73.1.93.

Powlishta, K. (2004). Gender as a social category: Inter-group processes and gender-role development. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 103–133). Hove: Psychology Press.

Quinn, D. M., Kallen, R. W., & Cathey, C. (2006). Body on my mind: The lingering effect of state self-objectification. Sex Roles, 55, 869–874. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9140-x.

Rogers, A. (1999). Barbie culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Schor, J. G. (2004). Born to buy: The commercialized child and the new consumer culture. New York: Scribner.

Starr, C. R., & Ferguson, G. M. (2012). Sexy dolls, sexy grade-schoolers? Media and maternal influences on young girls’ self-sexualization. Sex Roles, 67, 463–476. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0183-x.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

The World Bank. (2011). World development report 2012: Gender equality and development. Washington, D.C.: Author.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 24–98). Hoboken: Wiley.

Trautner, H. M., Ruble, D. N., Cyphers, L., Kirsten, B., Behrendt, R., & Hartmann, P. (2005). Rigidity and flexibility of gender stereotypes in childhood: Developmental or differential? Infant and Child Development, 14, 365–381. doi:10.1002/icd.399.

Turkel, A. R. (1998). All about Barbie: Distortions of a transitional object. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 26, 165–177.

Wilbourn, M. P., & Kee, D. W. (2010). Henry the nurse is a doctor too: Implicitly examining children’s gender stereotypes for male and female occupational roles. Sex Roles, 62, 670–683. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9773-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sherman, A.M., Zurbriggen, E.L. “Boys Can Be Anything”: Effect of Barbie Play on Girls’ Career Cognitions. Sex Roles 70, 195–208 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0347-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0347-y