Abstract

In the contemporary philosophical literature, political legitimacy is often identified with a right to rule. However, this term is problematic. First, if we accept an interest theory of rights, it often remains unclear whose interests justify a right to rule (the ‘grounds of authority’ question): either the interest of the holders of this right to rule or the interests of those subject to the authority. And second, if we analyse the right to rule in terms of Wesley Hohfeld’s characterization of rights, we find disagreement among philosophers about what constitutes the conceptual core of political authority: a power-right or a claim-right to rule (the ‘nature of authority question’). In this paper I show that both of these are problematic for a number of reasons. First, if we think that it is only the interests of the holders of a right to rule that justify the possession of authority, the conceptual core of authority must consist in a claim-right. However, this understanding of authority biases our thinking about legitimacy in favor of democratic exercises of power. Second, if we hold such a decisively democratic view of legitimacy, we confront an impasse with respect to addressing global collective action problems. Although it is clear that political authority is necessary or useful for solving these issues, it is doubtful that we can establish global institutions that are democratically authorized anytime soon. The paper suggests an alternative ‘Power-Right to Command View’ of political legitimacy that avoids the democratic bias and allows for thinking about solutions to global problems via global service authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I name proponents of both of these options in the next section.

It seems odd to think that Simmons takes this special right held against the subjects to be another power-right instead of a claim-right.

My thanks to Justin Tosi for his thoughts on the commitments of these theorists.

There is also a non-democratic version of the claim-right to rule view. However, for reasons explained in footnote 7, in this paper I confine my discussion of the claim-right to rule to (and refer to this view in terms of) the democratic interpretation of this idea.

I take Christiano to be an especially clear proponent of the democratic conception of the claim-right to rule view. However, Christiano also holds that there can be other forms of justified authorities like the bureaucracy of democratic states or even hostile but justified occupational forces (Christiano 2008, p. 241). Still, for him these other forms of authority are not primary notions of authority and often seem to be justified merely by their connection to democratic forms of authority (e.g. as in the case of the bureaucracy of a democratic state). For reasons I explain in footnote 22, I do not think that Christiano argues that non-democratic authorities are legitimate without deriving their justification from another, more basic democratic authority. However, even if Christiano would want to accept the idea of independent, non-democratic authorities suggested here, it still would be the case that anyone who holds the democratic right-to rule view would have to deny that there can be independently legitimate non-democratic authorities.

There are also cases where someone has a claim-right to our obedience if we have consented to this person having authority over us in a certain respect. We can think of the case of a guide who agrees to lead a tourist on a tour to the top of a mostly inactive volcano on the condition that the tourist unconditionally obeys her orders that pertain to this expedition. However, in the realm of politics such non-democratic instances of a claim-right to rule are not the norm and they do not generally explain the legitimacy of authorities that rule over large numbers of people. This is why Simmons (who is a proponent of this non-democratic claim-right view) argues that it is unlikely that there are any legitimate states (see Simmons 1979).

This is true irrespectively whether we think of interests as being necessary or merely sufficient for the justification of rights. I thank Andres Moles for helpful discussion on this point.

Jonathan Quong argues that the NJT generates problematically illiberal results since it seems to allow for someone to have authority over another person with respect to anything if it is true that she can help the other person to better act on the reasons that apply to that person. Thus, if I have the non-moral goal to go on a holiday trip to country A and there is a travel agency that can optimally arrange this trip for me it appears that Raz’s thesis gives this agency authority over me with respect to my planning of the trip. Quong points out that, to avoid such problematic conclusions, the NJT has to be restricted to cases in which a political authority can help us better to comply with moral reasons and duties that independently apply to us (see Quong 2011, chapter 4). However, there is evidence that Raz indeed thinks that in the case of political authority the NJT is in fact restricted to moral reasons that apply to persons when he says that ‘public authority is ultimately based on the moral duty which individuals owe their fellow humans’ (Raz 1986, p. 72).

This non-epistemic explanation of political legitimacy is indebted to Jerry Gaus’s idea of political authorities as umpires (Gaus 1996, pp. 188–191).

For these reasons, I think that those who advance the so-called ‘directionality thesis’ (see e.g. Darwall 2010) are mistaken in two respects: they are wrong to think that a legitimate authority-holder must herself possess a claim-right to being obeyed; and they are mistaken to think that legitimate authority requires a claim-right to be obeyed in the first place.

Other than their interest in having their moral equality respected in collective decision-making.

I choose this formulation to highlight the fact that service authorities do not possess a right to rule of the kind that is based on the interests of the right-holders (which would have to be a claim-right).

The difference between the democratic claim-right view and the service conception of authority is thus not a conceptual but a normative one. They disagree on which conception of authority is the normatively more fundamental one.

In this paper, I am not trying to answer the question whether democracy has intrinsic or instrumental value. My explanation of the way in which the service view of authority can relate to the importance of democracy is not committed to either of these ideas.

Raz (2006, p. 1031) agrees with this conditional relevance of democratic authorisation.

This is, of course, not a minor point. It is to say: whenever democratic authorisation is possible it is a necessary condition of political legitimacy. And surely also the subjects of non-democratic authorities have an interest in participating in the political decisions that deeply affect them. However, the point I make here is that in situations in which this interest cannot be realized authorities can be morally justified without respecting this interest in participation in political decision-making if they provide other indispensable services for their subjects.

This restrictive view is often attributed to Nagel (2005). However, it is possible to interpret Nagel’s argument in a more charitable way. Nagel uses the term ‘justice’ in an idiosyncratic way to refer only to egalitarian justice. Thus, on the charitable view of Nagel, his restriction of duties of distributive justice to associations that are ruled by one and the same authority can be read as merely limiting the concern for equality to these associative contexts. This would leave open the possibility that Nagel endorses a sufficiency principle of global distributive justice and only rejects the idea of global egalitarian justice. It could then be the case that common non-democratic international institutions can give rise to non-egalitarian global distributive duties of justice. But even on the charitable view, two of Nagel’s claims cause him to conclude that, due to the way our world is right now, questions of distributive justice do not arise at all in the global sphere. This is because he thinks that common authorities are a necessary condition for the enforcement of any duties of distributive justice, and because he also thinks that current democratic states have no obligations to establish common international authorities (Nagel 2005, pp. 121, 140). Thus, even on the charitable interpretation, Nagel’s argument generates the following problem: while non-egalitarian duties of global distributive justice might be conceivable as a result of common non-democratic global institutions, the possibility of egalitarian duties of global distributive justice depends on the existence of a common democratic authority.

It is of course a further question whether these unequal stakes are not themselves the result of an objectionable international order and how we ought to weigh different kinds of stakes against each other.

The same thought seems applicable to other global collective action problems such as climate change, the international tax competition, and the regulation of the international financial markets.

I take it the fact that Christiano thinks of this situation as an ‘impasse’ shows that he does not accept claim (c) that non-democratic authorities can be democratic on their own without some grounding in another democratic institution. If he would accept (c) he would not have to think of the current global situation as an impasse: if we need authoritative global coordination and decision-making, but no global democratic institutions are possible or desirable, we could (as the argument in this paper suggests) opt for creating non-democratic global service institutions to help us fulfil very salient moral duties and realize vital human interests. However, Christiano does not contemplate this option.

References

Applbaum, Arthur. 2010. Legitimacy without the duty to obey. Philosophy and Public Affairs 38: 215–239.

Buchanan, Allen. 2004. Justice, legitimacy, and self-determination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buchanan, Allen, and Robert O. Keohane. 2006. The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics and International Affairs 20: 405–437.

Buchanan, Allen. 2011. Reciprocal legitimation: Reframing the problem of international legitimacy. Politics, Philosophy and Economics 10: 5–19.

Christiano, Thomas. 2008. The constitution of equality: Democratic authority and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Christiano, Thomas. 2010. Democratic legitimacy and international institutions. In The philosophy of international law, ed. Samantha Besson, and John Tasioulas, 119–137. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Christiano, Thomas. 2012. Is democratic legitimacy possible for international institutions? In Global democracy: Normative and empirical perspectives, ed. Daniele Archibugi, Mathias Koenig-Archibugi, and Raffaele Marchetti, 69–95. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Copp, David. 1999. The idea of a legitimate state. Philosophy and Public Affairs 28: 3–45.

Darwall, Stephen. 2010. Authority and reasons: Exclusionary and second-personal. Ethics 120: 257–278.

Enoch, David. 2014. Authority and reason-giving. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 89: 296–332.

Estlund, David. 2008. Democratic authority: A philosophical framework. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gaus, Gerald. 1996. Justificatory liberalism: An essay in epistemology and political theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hershovitz, Scott. 2003. Legitimacy, democracy, and Razian authority. Legal Theory 9: 201–220.

Hohfeld, Wesley. 1919. Fundamental legal conceptions as applied in juridical reasoning. New Haven, NY: Yale University Press.

Hume, David. 1994. On the original contract. In Political essays, ed. Knud Haakonssen, 186–201. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klosko, George. 2005. Political obligations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Landemore, Hélène. 2012. Democratic reason: Politics, collective intelligence, and the rule of the many. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nagel, Thomas. 2005. The problem of global justice. Philosophy and Public Affairs 33: 113–147.

Perry, Stephen. 2013. Political authority and political justification. In Oxford studies in philosophy of law, vol. 2, ed. Leslie Green, and Brian Leiter, 1–74. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quong, Jonathan. 2011. Liberalism without perfection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raz, Joseph. 1985. Authority and justification. Philosophy and Public Affairs 14: 3–29.

Raz, Joseph. 1986. The morality of freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raz, Joseph. 1990. Practical reason and norms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raz, Joseph. 1994. Ethics in the public domain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Raz, Joseph. 2006. The problem of authority: Revisiting the service conception. Minnesota Law Review 90: 1003–1044.

Simmons, A. John. 1979. Moral principles and political obligations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Simmons, A. John. 2001. Justification and legitimacy: Essays on rights and obligations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steiner, Hillel. 1998. Working rights. In A debate over rights: Philosophical enquiries, ed. Matthew H. Kramer, Nigel E. Simmonds, and Hillel Steiner, 233–302. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tasioulas, John. 2010. The legitimacy of international law. In The philosophy of international law, ed. Samantha Besson, and John Tasioulas, 97–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

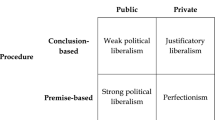

Viehoff, Daniel. 2011. Procedure and outcome in the justification of authority. Journal of Political Philosophy 19: 248–259.

Wenar, Leif. 2005. The nature of rights. Philosophy and Public Affairs 33: 223–252.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Jerry Gaus and Andrew Williams for their support and feedback, as well as to Nathan Adams and an anonymous reviewer of Res Publica for comments on prior versions. I am grateful to the British Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the doctorate from which this paper evolved. The final version of this publication was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) funded Cluster of Excellence “Normative Orders” at the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reglitz, M. Political Legitimacy Without a (Claim-) Right to Rule. Res Publica 21, 291–307 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-015-9267-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-015-9267-0