Abstract

This paper examines systematic differences in earnings persistence between high-tech (HT) and non-high-tech (NHT) firms in the presence of economic- and accounting-driven factors. We document that (1) HT firms, relative to NHT firms, show lower levels of earnings persistence, even after economic and accounting factors identified in prior research are controlled; (2) the type of HT products (durables) increases earnings persistence; and (3) the association between earnings persistence and discretionary accruals is higher in HT firms, possibly because HT mangers use discretionary accruals to convey private information about future cash flows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The pharmaceutical industry may seem incongruous with the rest of the industries in the high-tech group, other than the high cost of R&D. The pharmaceuticals are selected into the high-tech group because the extent to which accounting practices in this industry would generate unrecorded intangible assets is very high.

Improvements to software, hardware and IT processes can provide Securities brokers and dealers and other investing firms with a competitive advantage, and therefore these firms invest substantially in improving technology. Trading activities and services provided in these firms are influenced to a great extent by uncertainties in the markets. During periods of volatile markets, in uncertain regulatory or economic environment, there is a greater degree of variance between revenues and expenses in these firms.

Chang and Su (2010) recently demonstrate that R&D intensity in the electronics industry has a positive (negative) impact on sales growth when the level of such R&D intensity is below (above) the threshold value. Their evidence implies that the level of R&D intensity, relative to a threshold value, matters to the financial health of high-tech firms.

For the sample period, the average total assets and sales of NHT firms are approximately four times greater than those for HT firms. The average total assets (sales) of NHT firms is $3,706.88 million ($3,269.5 million), compared with $926.9 million ($844.59 million) for HT firms.

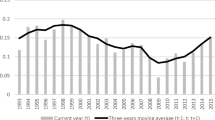

Givoly and Hayn (2000) also use assets and sales to control for inflation. In this study, since we compare accumulated nonoperating accruals between high-tech firms and low-tech firms year-by-year, the difference cannot be attributed to inflation.

TACCRi,t = ΔCAi,t − ΔCLi,t − ΔCashi,t + ΔSTDi,t − Depi,t, where, for firm i at time t, ΔCAi,t = change in current assets (item #4); ΔCLi,t = change in current liabilities (item #5); ΔCashi,t = change in cash and cash equivalents (item #1); ΔSTDi,t = change in debt included in current liabilities (item #34); and Depi,t = depreciation and amortization expense (item #14). We also calculate total accruals as the difference between net income and operating cash flows and results are similar.

In 2006 the FASB issued FAS 123(R) requiring companies that grant stock options to expense them. Since investment projects in high-tech firms usually are long-term, and new products take years to develop, HT firms are more likely to issue options to increase the horizon of managerial action and encourage managers to take on positive net projects that improve the future prospects. In addition, because HT firms require greater cash flow availability to develop new products and services, they are likely to substitute cash compensation with stock options. High option expense may affect the barrier to entry. We do not examine the use of stock options in this paper because before 2006 there was no requirement for firms to expense stock options.

A number of statistical programs are available to perform the principal component analysis. In this study, we use the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) to calculate the IOS index. Procedures of the principal component analysis are discussed in detail in Sharma (1996, 67–71).

In this paper, we find that (1 − Θ) = 0.914 (0.941) for HT (NHT) firms during the sample period of 1993–2005, which implies that Θ = 0.086 (0.059). Baber et al (1998, p. 176) use earnings per share data from 1974 to 1993 and find that mean value of the IMA parameter (1 − Θ) is 0.857 and hence Θ = 0.143. The difference between their results and our results possibly reflects differences in the sample period, sample size, and the data availability requirement. This study also reports the results based on an alternative time-series model, Integrated Autoregressive Process [ARI (1,1,0)].

References

Ahmed A, Duellman S (2007) Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: an empirical analysis. J Account Econ 43(2–3):411–437

Ali A, Zarowin P (1992) Permanent versus transitory components of annual earnings and estimation error in earnings response coefficients. J Account Econ 15(2–3):249–264

Amir E, Lev B (1996) Value-relevance of non-financial information: the wireless communications industry. J Account Econ 22(1–3):3–30

Baber WR, Kang SH, Kumar KR (1998) Accounting earnings and executive compensation: the role of earnings persistence. J Account Econ 25(2):169–193

Baginski SP, Lorek KS, Willinger GL, Branson BC (1999) The relationship between economic characteristics and alternative annual earnings persistence measures. Account Rev 74(1):105–120

Ball R, Watts R (1972) Some time-series properties of accounting income. J Financ 27:663–681

Bathke AW, Lorek K, Willinger GL (1989) Firm size and the predictive ability of quarterly earnings data. Account Rev 64(1):49–68

Beneish M, Vargus M (2002) Inside trading, earnings quality and accrual mispricing. Account Rev 77(4):755–791

Burgstahler DC, Eames MJ (2003) Earnings management to avoid losses and earnings decreases: are analysts fooled? Contemp Account Res 20(2):253–294

Chang H, Su C (2010) Is R&D always beneficial? Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Policies 13(1):157–174

Cheng Q, Warfield TD (2005) Equity incentives and earnings management. Account Rev 80(2):441–476

Collins DW, Kothari SP (1989) An analysis of the intertemporal and cross-sectional determinants of earnings response coefficients. J Account Econ 11(2–3):143–181

Connolly R, Hirschey M (1984) R&D, market structure and profits: a value-based approach. Rev Econ Stat 66:682–686

Dechow P, Ge W (2006) The persistence of earnings and cash flows and the role of special items: implications for the accrual anomaly. Rev Account Stud 11(2–3):253–296

Dichev ID, Tang VW (2008) Matching and the changing of property of accounting earnings over the last 40 years. Account Rev 83(6):1425–1460

Easton P, Zmijewski M (1989) Cross sectional variation in the stock market response to accounting earnings announcements. J Account Econ 11(2–3):117–142

Francis J, Schipper K (1999) Have financial statements lost their relevance? J Account Res 37(2):319–352

Frankel R, Litov L (2009) Earnings persistence. J Account Econ 47(1–2):182–190

Freeman R, Tse S (1992) A nonlinear model of security price response to accounting earnings. J Account Res 30(2):185–209

Givoly D, Hayn C (2000) The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: has financial reporting become more conservative? J Account Econ 29(3):287–320

Guay W, Kothari S, Watts R (1996) A market-based evaluation of discretionary accrual models. J Account Res 34(1):83–115

Gul FA, Leung S, Srinidhi B (2000) The effect of investment opportunity set and debt level on earnings-returns relationship and the pricing of discretionary accruals. Working Paper, City University of Hong Kong

Gustafson J (2008) 2009 Economic outlook: high-tech looks to weather storm. J Bus 23(26):B9

Hand J (2000) Profit, losses and the non-linear pricing of internet stocks. Working paper, University of North Carolina

Hand J, Landsman W (2005) The pricing of dividends in equity valuation. J Bus Financ Account 32(3&4):435–469

Huang Y, Zhang G (2011) The informativeness of analyst forecast revisions and the valuation of R&D-intensive firms. J Account Pub Pol 30(1):1–21

Kim BH, Pevzner M (2010) Conditional accounting conservatism and future negative surprises: an empirical investigation. J Account Pub Pol 29(4):311–329

Kormendi P, Lipe R (1987) Earnings innovations, earnings persistence, and stock returns. J Bus 60(3):323–345

Kothari SP, Leone AJ, Wasley CE (2005) Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. J Account Econ 39(1):163–197

Kumar KR, Krishnan GV (2008) The value-relevance of cash flows and accruals: the role of investment opportunities. Account Rev 83(4):997–1040

Kwon SS (2002) Financial analysts’ forecast accuracy and dispersion: high-tech versus low-tech stocks. Rev Quant Financ Account 19(1):65–91

Kwon SS, Yin J (2006) Executive compensation, investment opportunities, and earnings management: high-tech versus low-tech firms. J Account Aud Financ 21(2):119–148

Kwon SS, Yin QJ, Han J (2006) The effects of differential accounting conservatism on the ‘over-valuation’ of high-tech firms relative to low-tech firms. Rev Quant Financ Account 27(2):143–173

LaFond R, Watts R (2008) The information role of conservatism. Account Rev 83(2):447–478

Lai K (2009) Does audit quality matter more for firms with high investment opportunities? J Account Pub Pol 28(1):33–50

Lev B (1983) Some economic determinants of time-series properties of earnings. J Account Econ 5(April):31–48

Lookabill LL (1976) Some additional evidence on the time series properties of accounting earnings. Account Rev 51(October):724–738

Lorek K, Willnger GL (2007) The contexture nature of the predictive power of statistically-based quarterly earnings models. Rev Quant Financ Account 28(1):1–22

Martin S (1988) Market power and-or efficiency. Rev Econ Stat 70(2):331–335

McGuire ST, Omer TC, Wang D (2012) Tax avoidance: does tax-specific industry expertise make a difference? Accounting Rev 87(3):975–1003

McNees SK (1975) An evaluation of economic forecasts. N Engl Econ Rev 16:3–39

Mensah Y, Considine J, Oakes L (1994) Adverse public policy implications of the accounting conservatism doctrine: the case of premium rate regulation in the HMO industry. J Account Public Policy 13(4):305–331

Paek W, Chen LH, Sami H (2007) Accounting conservatism, earnings persistence and pricing multiples on earnings. Working Paper, Lehigh University

Rees WP (1997) The impact of dividends, debt and investment on valuation models. J Bus Financ Account 24(7&8):1111–1140

Ryan S, Zarowin P (1995) On the ability of the classical errors in variables approach to explain earnings response coefficients and R2s in alternative valuation models. J Account Audit Financ 10(4):767–786

Scott WR (2012) Financial accounting theory. Pearson, Canada

Sharma S (1996) Applied multivariate techniques. Wiley, New York

Skinner D, Sloan R (2002) Earnings surprises, growth expectations, and stock returns or don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Rev Account Stud 7(2/3):289–312

Sloan RG (1996) Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? Account Rev 71(3):289–315

Smith CW, Watts RL (1992) The investment opportunity set and corporate financing, dividend, and compensation policies. J Financ Econ 32(3):263–292

Stickney CP, Weil RL (2000) Financial accounting: an introduction to concepts, methods, and uses. 9th edn. The Dryden Press

Subramanyam KR (1996) The pricing of discretionary accruals. J Account Econ 22(1–3):249–281

Teoh S, Welch I, Wong T (1998) Earnings management and the underperformance of seasoned equity offerings. J of Financ Econ 50 (October):63–99

Trueman B, Wong F, Zhang X (2000) The eyeballs have it: searching for the value in internet stocks. J Account Res 38(3):137–162

Watts R (2003) Conservatism in accounting—part I: explanations and implications. Account Horiz 17(3):207–221

Watts R, Leftwich RW (1977) The time series of annual accounting earnings. J Account Res 15(2):253–271

White H (1980) Heteroskedasticity consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test of heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48(4):817–838

Acknowledgments

We thank Sharad Asthana, Jeff Boone, Jim Groff, Gordian Ndubizu, Emeka Nwaeze, April Poe, Inho Suk, two anonymous reviewers, as well as participants at the 2012 SWAAA Conference, the 2011 American Accounting Association Conference, the 2011 Canadian Academic Accounting Association Conference, and the University of Texas at San Antonio workshop for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Earnings persistence proxies

Appendix: Earnings persistence proxies

Earnings persistence is defined as the degree to which future earnings are induced by a $1.00 innovation in current earnings. Valuation theory suggests that analysts and investors should put greater emphasis on forecasting high-persistence earnings than low-persistence earnings, because changes in high-persistence earnings have a greater valuation impact than the same changes in low-persistence earnings. This time series properties of earnings (earnings persistence) are positively related to ERC, the magnitude of relation between earnings and returns (Kormendi and Lipe, 1987; Easton and Zmijewski 1989; Collins and Kothari, 1989).

Comparing values of an unexpected dollar of permanent earnings and transitory earnings explains the role of persistence. Empirical studies predict that transitory earnings surprises have an ERC of one and that the ERC of permanent earnings is one plus the inverse of the discount rate. Therefore, analysts and investors are relatively uninterested in transitory earnings because the trading profits that could be earned from private foreknowledge of a dollar of transitory earnings are smaller than the profits earned from private foreknowledge of a dollar of permanent earnings (Freeman and Tse 1992).

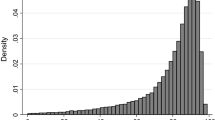

Since earnings follow a non-stationary process, earnings persistence can be measured better with a first differenced time-series model. In order to estimate firm-specific persistence levels, we adopt an ARIMA (1,1, 0) or ARI (1,1,0) (Kormendi and Lipe 1987; Easton and Zmijewski 1989) and an IMAMA (0,1,1) or IMA (0,1,1) (Collins and Kothari 1989; Ali and Zarowin 1992; Baber et al. 1998) time-series characterization of quarterly earnings. These consider seasonality of quarterly earnings and facilitate parsimonious empirical specifications of both earnings innovations and earnings persistence.

The ARI (1,1,0) model, or the first differenced AR(1) model with seasonality. Can be expressed as follows:

where X is quarterly actual earnings, ϕ is persistence parameter, B is backshift operator and a t is white noise. This also can be represented as

where ϕ is a firm-specific persistence level estimate measured by the autocorrelations of seasonally differenced earnings over the 32 quarters that end in each year of the sample period 1993–2005.

If ϕ is low, then current-earnings innovation would be more transitory. On the other hand if ϕ is high, then current-earnings innovation would be more permanent. Thus, ϕ measures the extent to which earnings innovations are permanent or transitory and quantifies the notion of earnings persistence.

The IMA (0,1,1) model with seasonality also can be expressed as:

If θ = 1, then earnings follow a mean reverting process, and earnings innovations are expected to be transitory. In contrast, when θ = 0, earnings follow a random walk process, and earnings innovations are expected to be permanent. Thus parameter (1 − θ) measures the extent of the persistence level.Footnote 12

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, S.S., Yin, J. A comparison of earnings persistence in high-tech and non-high-tech firms. Rev Quant Finan Acc 44, 645–668 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-013-0421-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-013-0421-5