Abstract

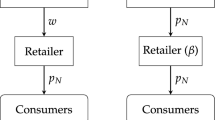

The Supreme Court’s reasoning in Leegin turned on the insight that manufacturers may use resale price maintenance (RPM) for procompetitive purposes. This paper presents a model of manufacturer-retailer interactions that clarifies why, as a rule, retailers and manufacturers are joint beneficiaries of service-inducing RPM. The model identifies factors that determine how RPM-generated benefits are allocated between a manufacturer and its retailers. The paper then shows that manufacturers may use market share discounts (MSD) in lieu of RPM or other vertical restraints to induce retailer performance. The outcomes and efficiency effects that are achieved with RPM can be replicated and usually surpassed if manufacturers substitute MSD for RPM, thereby enabling a manufacturer to retain all incremental profit rather than conceding some of it to retailers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Across-the-board hostility toward vertical non-price restraints broke down first. The Court’s decision in Continental T.V. Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36 (1977), directed that these vertical arrangements be submitted to a rule-of-reason analysis.

Mathewson and Winter (1998, p. 59) aver that “RPM is the most important vertical restraint in terms of both the frequency of use and the number of legal cases generated.”.

To be sure, there are anticompetitive theories of RPM that warrant continued antitrust vigilance. These theories mainly involve horizontal price-fixing: either upstream or downstream. Mathewson and Winter (1998) and Elzinga and Mills (2008), among others, enumerate and distinguish both the various procompetitive and anticompetitive theories of RPM.

See also Telser (1990).

Nor does it apply to Deneckere, Marvel, and Peck’s (1997) theory that RPM keeps retail prices from falling too far during periods of unexpected slack demand and deterring retailers from carrying inventories that are too lean from the perspective of the manufacturer, or to Inderst and Pfeil’s (2014) “image theory” of RPM.

The assumption that \( z > v - c \) simplifies the analysis, but it is not strictly necessary for the principal results that follow.

The Court’s Leegin opinion acknowledges that“[r]etail price maintenance can … increase interbrand competition by facilitating market entry for new firms and brands and by encouraging retailer services that would not be provided … absent free riding” (p. 2).

Mathewson and Winter (1998, p. 60) note that “RPM is often used in the early part of a product’s life cycle to aid in the establishment of the distribution system.”.

The discount can be remitted to retailers in the form of a rebate to assure performance.

Kolay, Shaffer, and Ordover (2004) show that a manufacturer may use an all-units volume discount as an incentive for retailers to increase downstream sales, thereby overcoming the double-marginalization problem.

The free-rider problem that Telser identified extends to the “quality certification” service that a retailer with a reputation for selling high-quality merchandise provides manufacturers (Marvel and McCafferty, 1984). A manufacturer may use RPM to insure that such retailers are not deterred from carrying the manufacturer’s brand by free-riding discounters. A market-share incentive program is not a good substitute for RPM for eliciting this kind of retailer service. This is because quality certification is a market signal that depends on whether the retailer carries the manufacturer’s brand and not on how many units of that brand the retailer sells.

Even a program of individualized volume discounts could replicate the outcome of “one size fits all” MSD only where aggregate demand is stationary. Zenger (2012, p. 756) notes that “market share contracts render rebate thresholds insensitive to aggregate demand fluctuations, which enables firms to compete for marginal sales in the face of uncertain demand.”.

Although both RPM and MSD increase total welfare, neither increases consumer welfare in this model. This is due to the simplifying assumption that reservation values for brand M for every M-preferring consumer and every susceptible consumer are the same. If consumers’ reservation values were different, then both RPM and MSD may increase consumer welfare. There is a small increase in consumer welfare, for instance, if a small number of susceptible consumers have latent reservation values for brand M of \( v + z + \delta , \) \( {\text{where}}\;\delta \;{\text{is}}\;{\text{small}}. \)

Most states enacted “fair trade” laws after the Miller-Tydings Act of 1937, but this law was repealed in 1975. Also, U.S. v. Colgate & Co., 250 U.S. 300 (1919) established the “Colgate doctrine,” which permitted manufacturers to unilaterally terminate dealers or retailers who do not charge manufacturers’ “suggested retail prices.” .

Bernheim and Heeb (2014), for instance, emphasize that the efficiency effects of a business practice must be weighed against any exclusionary effects to determine whether the practice is anticompetitive.

This outcome is precluded in the present model by the assumption that manufacturers of undifferentiated brands produce with constant returns to scale and therefore could survive with arbitrarily low output levels.

Inderst and Shaffer (2010) show that the welfare effects of MSD may be positive or negative when used in combination with two-part pricing.

Federal Trade Commissioner Wright (2013) advocates assessing the legality of loyalty discounts such as MSD in the same manner as assessing the legality of exclusive dealing. A lively sequence of reactions to this position appears on the antitrust law and economics blog https://truthonthemarket.com.

Competition law in the E.U. is notably more hostile to loyalty rebates such as MSD. This hostility rises almost to the level of that toward RPM during the Dr. Miles era. Zenger (2012, p. 718) writes that “the treatment of loyalty rebates under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is perhaps the most heavily disputed field of European competition policy. Relying mainly on a presumption that rebates are incompatible with the competitive process, the Community Courts have consistently prohibited pricing schemes by dominant firms that involve loyalty discounts unless they are cost-based.”.

References

Bernheim, B. D., & Heeb, R. A. (2014). Framework for the economic analysis of exclusionary conduct. In R. D. Blair & D. D. Sokol (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international antitrust economics (Vol. 2, pp. 2–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deneckere, R., Marvel, H. P., & Peck, J. (1997). Demand uncertainty and price maintenance: Markdowns as destructive competition. American Economic Review, 87, 619–641.

Elzinga, K. G., & Mills, D. E. (2008). The economics of resale price maintenance. In W. D. Collins (Ed.), Issues in competition law and policy (Vol. 3, pp. 1841–1858). Chicago: American Bar Association.

Faella, G. (2008). The Antitrust assessment of loyalty discounts and rebates. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 4, 375–410.

Hovenkamp, H. (2005). The antitrust enterprise. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Inderst, R. & Pfeil, S. (2014). An “Image Theory” of RPM. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/54139/.

Inderst, R., & Shaffer, G. (2010). Market-share contracts as facilitating practices. RAND Journal of Economics, 41, 709–729.

Klein, B., & Murphy, K. M. (1988). Vertical restraints as contract enforcement mechanisms. Journal of Law and Economics, 31, 265–297.

Kobayashi, B. H. (2005). The economics of loyalty discounts and antitrust law in the United States. Competition Policy International, 1, 115–148.

Kolay, S., Shaffer, G., & Ordover, J. A. (2004). All-units discounts in retail contracts. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 13, 429–459.

Kovacic, W. E., & Shapiro, C. (2000). Antitrust policy: A century of economic and legal thinking. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 43–60.

Marvel, H. P. (1982). Exclusive dealing. Journal of Law and Economics, 1, 6–11.

Marvel, H. P., & McCafferty, S. (1984). Resale price maintenance and quality certification. RAND Journal of Economics, 15, 346–359.

Mathewson, F., & Winter, R. (1998). The law and economics of resale price maintenance. Review of Industrial Organization, 13, 57–84.

Spector, D. (2005). Loyalty rebates: An assessment of competition concerns and a proposed structured rule of reason. Competition Policy International, 1, 89–114.

Telser, L. G. (1960). Why should manufacturers want fair trade? Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 86–105.

Telser, L. G. (1990). Why should manufacturers want fair trade II? Journal of Law and Economics, 33, 409–417.

Tom, W. K., Balto, D. A., & Averitt, N. W. (2000). Anticompetitive aspects of market-share discounts and other incentives to exclusive dealing. Antitrust Law Journal, 67, 615–639.

Whinston, M. D. (1990). Tying, foreclosure, and exclusion. American Economic Review, 80, 837–859.

White, L. J. (2010). Economics, economists, and antitrust: a tale of growing influence. In J. J. Siegfried (Ed.), Better living through economics (pp. 226–248). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wright, J. D. (2013). Simple but wrong or complex but more accurate? In The case for an exclusive dealing-based approach to evaluating loyalty discounts, remarks at the Bates White 10th annual antitrust conference. https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2013/06/simple-wrong-or-complex-more-accurate-case-exclusive-dealing-based.

Zenger, H. (2012). Loyalty rebates and the competitive process. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 8, 717–768.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mills, D.E. Inducing Cooperation with a Carrot Instead of a Stick. Rev Ind Organ 50, 245–261 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-017-9563-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-017-9563-2