Abstract

This article analyzes how transaction costs influence the ability to charge nonlinear prices and how market structure and industry behavior affect those transaction costs. The failure to recognize that nonlinear pricing produces a different equilibrium than linear pricing together with a recognition that the pricing mechanism can be altered by conduct under antitrust review explains why the usual antitrust analysis can be misleading. The paper illustrates its points using merger simulations with nonlinear pricing. Finally, the paper analyzes how to identify situations where market power might arise and applies the analysis to exclusive dealing, credit cards and FRAND royalties.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Coase (1960) altered fundamentally how most economists think about externalities and government intervention. Coase made the point that in a world with well-defined property rights and no transaction costs, parties would always wind up at an efficient point, thereby eliminating externalities and the need for government intervention.

But Coase’s main point was that we do not live in such a world and that by the assignment of property rights, a government can influence transaction costs and thereby the ability of the economy to reach an efficient point. Therefore, a government should assign property rights in order to enable the economy to reach an efficient solution.Footnote 1

We explore in this article the implications of Coase’s insights for antitrust and show how Coase’s insights mean that we should refocus much or at least some of our economic analysis of the antitrust issues that are related to mergers and market power. This article together with a companion paper (Carlton and Keating forthcoming) makes several points that are related to transaction costs and antitrust.

In the absence of transaction costs, output would be at the efficient level, and there would be no deadweight loss, and hence no need for antitrust if one uses a total surplus criterion (Demsetz 1968). Since there are transaction costs, it is important for an antitrust analysis to examine whether they are sufficiently low to enable nonlinear pricing; and, if not, whether the conduct that is under scrutiny lowers transaction costs so as to allow the use of nonlinear pricing. Failure to account for the use of nonlinear pricing can lead to a mistaken antitrust analysis—especially when efficiencies are involved.

Finally, the cost of creating a coalition of economic agents is related to transaction costs. Cooperative game theory tells us that one can view all of antitrust in a unified way as the creation of one coalition that exploits the non-coalition members. By studying when coalition formation is low and high, one can identify situations where the creation of market power is possible.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the foundational model of antitrust in which a firm (or group of firms) maintains a uniform price that is above marginal cost, restricts output (below the level that would be dictated by the criterion of price equals marginal cost), and harms consumer and total welfare. For example, the famous Williamson diagram (Williamson 1968) is still the way mergers are often thought of—with the deadweight loss from the merger’s consequence of raising the price offset in part or in total by the efficiency gain from the lowered costs that are also the consequence of the merger.

But Coase’s insight forces us to focus on transaction costs in our analysis. What prevents any firm with market power from eliminating the deadweight loss that is typically associated with that market power? How does competition affect that transaction cost, and how will that transaction cost be altered by a change in market structure or by certain conduct such as the imposition of vertical restrictions? Section 2 explores these questions and shows that only by answering them can we hope to understand the antitrust implications of a merger or of specific conduct that comes under antitrust scrutiny.

To illustrate the importance of transaction costs in an antitrust analysis, Sect. 3 summarizes some merger simulations from Carlton and Keating (forthcoming), where a merger simulation with nonlinear pricing is developed and where the results show that the usual merger simulation with uniform pricing can yield misleading results. Finally, Sect. 4 describes how all of antitrust, including both horizontal and vertical behavior, can be thought of as the creation of one coalition that exploits the non-members of the coalition. By focusing on the transaction costs of creating various coalitions, one can identify when antitrust violations are most likely to occur. We illustrate these ideas by applying them to exclusive dealing, credit card firms, and the setting of royalties in standard-setting associations.

2 Coase, Transaction Costs, and Deadweight Loss

As explained in the Introduction, Coase’s insight is that there is no deadweight loss in the absence of transaction costs. If there is to be a concern about the inefficiency that is created by market power, it must be true that transaction costs exist to impede achievement of efficiency. (Of course, even if total surplus is maximized, consumer surplus can be lowered by the use of market power. All of our results apply even when the objective is to maximize consumer surplus.) By transaction costs, we mean those costs that provide the information to a firm on how to price as well as those costs that a firm must incur to prevent arbitrage among consumers to whom the firm is charging different prices. In this section, we describe several examples where either the industry practices or market structure affects these transaction costs.

Although we hope these examples (and those in our companion paper) are persuasive to the skeptical reader, we note that the point about market structure’s influencing the ability to engage in non-uniform pricing is actually an old one in industrial organization. The classic example is the vertical integration of Alcoa before the 1940s. Alcoa vertically integrated forward into the high-elasticity end products that used aluminum ingot, and thereby attained the ability to prevent arbitrage. This enabled Alcoa effectively to practice price discrimination between the producers of the low- and high- elasticity end products. This example is often used to explain Alcoa’s decisions to integrate vertically into certain end products (and not others) that used aluminum ingots—the product that was assumed to be monopolized by Alcoa—as an input (see Carlton and Perloff 2004).

The required effort and cost to engage in nonlinear pricing may well depend on firm conduct and industry market structure. Hence, firm conduct or market structure (or changes in them) can affect the relevant transaction costs. Let us illustrate this last point with several examples, each of which is interesting in its own right since each is related to many situations that arise routinely in antitrust. Each of the examples shows that the ability to practice nonlinear pricing can be influenced by conduct that often raises antitrust scrutiny.

2.1 Firm Conduct–Loyalty Discounts

Suppose a dominant firm institutes a policy of granting loyalty discounts as long as a customer buys 80 % of its aggregate purchases of that category of inputs from the firm. This can clearly be a way for a firm to gain information about the total demand of the customer—information that the firm might otherwise have a hard time figuring out. Armed with this information, the firm could figure out how this customer’s demand varies over the business cycle and could devise various types of nonlinear (including discriminatory) pricing mechanisms. These mechanisms could enable both the customer and the firm to be better off because, absent the information, the customer might be faced with a linear price schedule that we know is inefficient in the presence of market power to the extent that price exceeds marginal cost.

Many times these pricing schemes are claimed to be exclusionary, and that might well be so. But the fact that the schemes allow nonlinear pricing could be a benefit that outweighs the exclusionary effects. Of course, if the exclusionary effect is substantial so that the effect of the pricing scheme is to prevent what would otherwise be competitive pricing, then we know that there is an antitrust harm.

2.2 Merger to Monopoly with Efficiencies

As another example, consider a merger to monopoly of two firms, where the merger creates some productive efficiency. One standard analysis is to ask by how much the price under monopoly will rise compared to the price under duopoly. The analyst will attempt to determine whether the efficiency gain offsets the harm from the loss of competition. But that analysis holds constant the pricing mechanism; it assumes the use of uniform pricing both pre- and post-merger.

But why is that a good assumption? Following Coase, we know that the outcome with uniform pricing can be improved upon from society’s viewpoint as long as the transaction costs are not too high for such a pricing mechanism, and we know that all parties can be made better off under such a mechanism. We also know that the ability to price discriminate can be made more difficult by the presence of competing firms. In the presence of a competing firm, any attempt to charge some customers higher prices on average may be easy to undermine, as the customers that pay the higher average prices turn to others that may be able to purchase and then resell at lower prices—especially as resale may be facilitated by the competing firm. Therefore, it may be possible to use more sophisticated pricing mechanisms post-merger than uniform pricing because of the elimination of competition.

Suppose that it is possible to use two-part tariffs rather than uniform pricing post-merger, because of the lowered transaction costs of engaging in non-uniform pricing. Might that not be relevant to determining the desirability of the merger? We are unaware of such merger simulations that involve nonlinear pricing in the existing economics literature; but in the next section we summarize some results from the recent development of such a model (see Carlton and Keating forthcoming).

The results show that this nonlinear pricing model can give very different answers with regard to the desirability of a merger compared to our standard merger simulation, especially in the presence of production efficiencies. One reason is that production efficiencies are most important when output is large. Since output is likely greater with nonlinear pricing than with linear pricing, it follows that one likely effect of a traditional analysis that assumes linear pricing is to underestimate the efficiency gains from a merger when the merger will lead to production efficiencies and also to a more sophisticated pricing mechanism. In essence, the more sophisticated pricing can significantly alter the evaluation of the merger compared to an analysis that assumes uniform pricing.

This example involved a horizontal merger. Similar principles apply to vertical mergers. We give two examples: The first involves a common concern that is related to vertical foreclosure, while the second involves a combination of vertical and horizontal concerns.

2.3 Vertical Merger to Foreclose

Suppose that an input monopolist sells to several downstream firms that compete amongst themselves. The monopolist buys one of the downstream firms. The other downstream firms complain that the merged firm will have an incentive to foreclose them from (or raise their costs for) the input in order to benefit the downstream division of the vertically integrated firm. There are numerous models of such foreclosure in the literature (see, e.g., Ordover et al. 1990). Most, if not all, of the models that involve vertical foreclosure assume some inefficient pricing between firms and then show, depending on the details of the assumptions (e.g., Cournot vs. Bertrand), that the vertical integration can cause harm through foreclosure.

But the analyst should ask what merger-generated changes make foreclosure more likely than it was pre-merger. If, pre-merger, the input monopolist could have contracted with one “independent” downstream firm (e.g., the firm that it is merging with), told the firm “hey, I will advantage you relative to your rivals, so let’s share the profits,” then there would be no gain from the vertical integration.

Suppose that the market conditions pre-merger were such that there were a large number of very detailed and complicated contracts that involved terms that defined nonlinear pricing and exclusion of rivals. Then why should one assume that exclusion would occur post-merger when it does not occur pre-merger when such contracts appear feasible? The only reason would be that the transaction cost of the exclusionary contract that I have just described becomes easier to carry out when the firm is integrated. But why?

If that question cannot be answered, then the regulatory or antitrust authority should be skeptical of the foreclosure argument.Footnote 2 Indeed, one might think that, at least sometimes, it is easier to get away with an exclusionary contract (which is hard to observe) compared to avoiding detection of the possibility of the exclusionary act when there is the full scrutiny of a regulatory or antitrust agency that is evaluating a vertical merger and can impose conditions to prevent exclusion. This is especially possible if there is a regulatory body involved, such as the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), that operates under a different statutory standard than, say, an antitrust authority.Footnote 3

2.4 Horizontal Merger that Leads to Vertical Antitrust Concerns

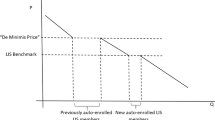

As a final example that shows how the transaction costs of implementing a price mechanism can change as a result of some antitrust act, consider a horizontal merger that will have vertical implications. Suppose that there is a monopolist that sells to many buyers. Because of either a lack of information or the difficulty in preventing arbitrage, the monopolist can charge only a uniform monopoly price to the many buyers.

Suppose now that several of the buyers merge to form one large firm. In that case, it is easy to imagine a situation in which the large buyer can negotiate with the monopolist while the many remaining small buyers cannot because it is too costly. The large buyer may be able credibly to commit not to engage in arbitrage, succeed in obtaining a lower marginal price than its constituent firms had previously paid, and split the gains of its output expansion with the monopolist through some lump-sum payment (i.e., nonlinear pricing is used for the largest buyer).Footnote 4

The analysis of the consequences of the creation of a large buyer through merger must take into account the changed pricing mechanism that results as a consequence of the merger. The outcome could raise total surplus overall, lead to an expansion of output, and could in principle lead to a harm to the small buyers. If for example, the small buyers have a lower demand elasticity than the large buyer, the small buyers could see their prices rise after the merger. It is problematic to require that a merger, in order to pass antitrust scrutiny, must make each buyer better off (or no worse off), and we would settle for a total surplus (or total consumer surplus) approach, though others may differ.Footnote 5

There is an interesting antitrust wrinkle in this last example: Suppose that the buyers are not final consumers but instead purchase an input from the monopolist and then compete with each other in an output market. Then the higher marginal input price to the small buyers obviously could enhance the market power that the large buyer has in the output market. If the presence of small firms in that output market prevents the large buyer from pricing efficiently (price discriminating) to its customers, then the elimination of the small input buyers through high input prices could lead to even higher profits for our large buyer than would otherwise occur from just the elimination of its competition because the large buyer also becomes better able to price discriminate. If so, then the large buyer and the input monopolist can coordinate and destroy the small buyers, leading to a price-discriminating monopoly in the output market. Then those monopoly profits in the output market can be split (with some attendant transaction cost, no doubt) between the now two monopolists—the input- and output-monopolists.Footnote 6

Notice that even if all input buyers—small and large—could coordinate and bargain efficiently with the input monopolist to obtain marginal cost pricing, the large buyer would refuse because he can make more money by striking a bargain with the input monopolist to drive out the small input buyers. Suppose that we consider the gain to the large buyer from having the monopolist charge a high price to its rivals (the small buyers). Part of that gain comes from the fact that the advantaged large buyer will be able to exercise monopoly power over its consumers in a way not possible before.Footnote 7 By eliminating the competitive constraints on the pricing mechanism in the large buyer’s market, the input monopolist can cause the large buyer’s profits to increase with the result that the input monopolist can capture some of that extra profit for itself.

Of course, we would need to investigate why there is market power in that output market, whether the market power creates deadweight loss, what coalitions can form, and how costly it is for them to form; but it is easy to see that the best way for our input monopolist to exploit his market power could be to skew competition in downstream markets, favor the large buyer, enable the large buyer to price discriminate (through the weakening of the competitive constraints on output pricing by the small buyers), and share in some of the increased downstream profits.Footnote 8 Whether this is the best way to exploit his power will again depend on all the relative transaction costs of dealing with the various coalitions.

The key point is that a central issue in many antitrust matters is how the conduct under antitrust scrutiny alters the ability to exploit the existing and/or newly-created market power. We rarely, if ever, think of things that way. We should, but do not, pay attention to how the various transaction costs of organizing groups both horizontally and vertically may change as a result of a changed market structure.

3 Merger Simulation with Nonlinear Pricing

The previous section described how certain industry practices or conduct (i.e., merger) could influence the ability of firms to practice nonlinear pricing. In this section, we report on how the usual type of antitrust analysis in which one focuses on uniform pricing before and after the merger can lead to erroneous conclusions.Footnote 9

Carlton and Keating (forthcoming) develop and implement a merger simulation model with nonlinear pricing. We report below the results of merger simulation with and without nonlinear pricing (two-part tariffs) and with and without efficiencies.Footnote 10 The simulations assume that there are two firms that pre-merger compete as differentiated-product Bertrand rivals and post-merger behave as a two-product monopoly. Demand curves are linear, consumers have heterogeneous tastes for each of the firm’s products, and production is characterized by constant returns to scale. There is also a constant cost to attract a consumer to a firm’s product.Footnote 11 Each consumer consumes only one of the two firm’s products after he compares the surplus he gets from each of the firm’s two-part tariffs.

We report in Table 1 a summary of the results for a merger that involves no efficiencies. There are several points to note about the results: First, the output is always higher—as is total and consumer surplus—in any market structure when two-part tariffs are used instead of uniform pricing. For example, post-merger, consumer surplus rises from $0.72 to $0.97 when two-part tariffs are used instead of uniform pricing.

Second, if the pricing mechanism does not change, then the merger harms consumers and reduces total surplus. For example, in columns (1) and (2) total surplus falls from $1.54 to $1.39 with uniform pricing and from $2.06 to $2.03 with two-part tariffs.

Third, and perhaps most important, if the merger enables the firm to use two-part pricing instead of uniform pricing, then the merger increases total (and consumer) surplus. For example, total surplus rises from its pre-merger value of $1.54 with uniform pricing to its post-merger value of $2.03 with two-part tariffs. That is, the merger should be approved once one takes account of the efficiency that the merger creates by enabling the use of a nonlinear pricing mechanism.

Table 2 summarizes the simulation results of Carlton and Keating (forthcoming) when there are marginal cost efficiencies. The simulation assumes a very modest efficiency of 3 % in the production costs of one product.

Table 2 makes two points: First, it shows that a merger that would be deemed anticompetitive under uniform pricing becomes procompetitive if two-part tariffs are used both pre- and post-merger. Specifically, under uniform pricing, consumer surplus falls from $0.90 to $0.78, but with two-part tariffs the consumer surplus rises from its pre-merger value of $1.00 to $1.04. The reason is that with the greater output associated with the use of two-part tariffs (from Table 2, post-merger output is 0.74 with uniform pricing versus 1.13 with the two-part tariff), the efficiencies matter much more than under uniform pricing.

Second, to the extent that the merger also allows for the firm to adopt nonlinear pricing instead of uniform pricing, then there is an additional merger benefit. The combination of the two benefits—the production efficiency and the pricing technology efficiency—reinforce one another.

Hence, an analysis that takes account of both sources of efficiencies can find much larger benefits than an analysis that ignores those sources of efficiencies. For example, in Table 1 we saw that with uniform pricing, the merger reduced consumer surplus from $0.90 to $0.72; but with just a 3 % merger-induced production efficiency that is combined with the merger-enabled ability to use a two-part tariff, consumer surplus post-merger rises to $1.04.

This example illustrates that the usual merger analysis that assumes uniform prices can be quite misleading in the presence of nonlinear pricing and efficiencies. Indeed, the answer to the question of whether a merger will improve consumer or society’s welfare can be wrong when one adopts the usual practice of ignoring the existence of nonlinear pricing.

4 Transaction Costs and Coalitions

Virtually all models and analyses that we have seen that analyze anticompetitive conduct make the implicit assumption that certain transaction costs are low and certain ones are high. Most industrial organization economists make these assumptions naturally when performing an antitrust analysis and likely do not think about them much.

For example, imagine a situation where a large number of firms are competing. Although it is well understood that those firms might well gain if they could coordinate and behave as a cartel, the transaction costs of doing so might be so high as to preclude that outcome, even in the absence of antitrust laws that prohibit such behavior.

However, if there were to be a merger among many of these firms, then presumably a common pricing authority within a firm could enable prices of the formerly independent firms to be “coordinated” easily. That is the underlying intuition for why merger policy is concerned about increased concentration that leads to higher prices.

That concern is implicitly based on an underlying assumption regarding transaction costs. That reasoning, of course, makes a lot of sense; but we would like to recast what may appear obvious in order to highlight how the recasting can help identify quite clearly certain circumstances when antitrust harms are most likely to occur.

To be concrete, we will illustrate our point by examining three areas where it is understood how certain actions can sometimes generate antitrust harm: vertical restrictions on distributors with exclusive dealing; collective action by buyers that is achieved through the formation of a firm, as is illustrated by credit card firms; and standard-setting.

Let us begin by introducing some slightly cumbersome notation. Let m be a set that consists of all of the manufacturers in the industry; let d be the set of all of the distributors; and let c be the set of all of the consumers of the product. Let M be the set that consists of all of the subsets of m, D be the set of all of the subsets of d, and C be the set of all of the subsets of c.

We want the reader now to consider all possible coalitions of manufacturers, distributors, and consumers (M, F, C)—that is, a grand set of coalitions that consist of some manufacturers, some distributors, and some consumers. Each such coalition has associated with it a transaction cost of organizing.

The theory of the core teaches us that under certain circumstances a competitive (price-taking) equilibrium exists, is unique, and has the property that there is no coalition that can form that can improve the well-being of its members.Footnote 12 In the typical exposition of the theory of the core, transaction costs are taken as zero.

We now want to introduce positive transaction costs to explain how an antitrust harm can occur.Footnote 13 We have already seen one standard instance in the example where the transaction costs of coordinating price among many horizontal competitors are high so that a merger could lower those transaction costs of coordinating, thereby leading to elevated pricing. It makes sense in that setting to assume that each of the many consumers might not find it worth their while to form coalitions to negotiate with a firm with market power and return the equilibrium to an efficient point. Let us see when else transaction costs can help identify an anticompetitive possibility.

4.1 Vertical Restrictions: The Case of Exclusive Dealing

In any model where vertical restrictions are used to create an anticompetitive harm, it has to be the case that the participating distributors and manufacturing firm are collectively better off while consumers (and perhaps others) are worse off as a result of the restriction. Consider the standard example of foreclosure by a dominant firm of its rivals by the use of exclusive dealing. As the story goes, there are only a few distributors, there are scale economies, and the dominant firm locks up the major distributors through exclusive dealing contracts.Footnote 14 This can be thought of as the distributors forming a coalition with the dominant firm to exclude rivals to the dominant firm, thereby allowing the dominant firm to remain a dominant firm and reap profits, some of which it can share with its coalition partners (the distributors).Footnote 15 Exactly how much the dominant firm has to share with the distributors will depend on how important the marginal distributor is and that could range from zero to a lot.Footnote 16

But a moment’s thought will reveal that the harmed buyers could form a coalition and bribe the distributors to enable entry of competing manufacturers. That of course sounds pretty hard to do—high transaction costs of organizing lots of small consumers into a group. But not so fast. Why can’t a distributor or potential entrant manufacturer act on behalf of its future customers and engage in the transaction and create competition?

We think that the best answer is that that is complicated to do because there is no easy way (or it is too costly) to bind future consumers to purchase from the negotiating firm. It is the difficulty of dealing with future customers that makes transaction costs especially high in this situation. That is why exclusionary conduct can sometimes succeed.Footnote 17

Indeed, we suspect that transaction costs are an important reason for why it is easier to exclude entrants than it is to exclude established firms with established customer relations. Indeed, if dealing with future consumers creates high transaction costs, then one should expect that entry deterrence will work best when the current product is durable and sold (not rented),Footnote 18 when there are scale economies, and when the future consumption of any individual consumer is uncertain. In those circumstances, the transaction cost of guaranteeing a profitable entry may become high, and therefore exclusionary conduct can successfully deter entry.

4.2 The Firm as a Negotiating Agent for a Collective of Buyers: Credit Cards

The previous example alluded to the possibility that a firm could act as a collective bargaining agent for its customers. That means that a firm can be a way for what would otherwise be an illegal collective of buyers to form and negotiate prices on behalf of its “customers” and perhaps harm either suppliers or other consumer groups. Let us give an example that comes from the literature on two-sided markets: credit cards.

Suppose all the rich buyers in the United States band together to form the “rich buying club.” The club goes to all the major stores and says that its members will boycott any store that fails to recognize the club. Furthermore, whenever any member of the club buys something, the retail store is required to make a small payment—say 1 % of the purchase price—to the club. The club then keeps some of the money for itself and gives some to its club members.

Suppose further that the club imposes a requirement on any store that recognizes the club that the store must charge club members and non-club members the exact same retail price. Without that restriction, the 1 % club fee would likely be passed along at least in part to club members at the point of sale in terms of an elevated retail price. With the price restriction in place, the store must recover any increased costs of dealing with club members from all of its customers—a form of average cost pricing. Another way to view what has happened as a result of the operation of the club with its restrictions is that the members of the “rich buying club” have forced the stores to place a “tax” on club and non-club buyers and to send that tax revenue to the club, which then distributes some of the tax revenue to its members and keeps the remainder for itself.

Our description in this example is reasonably close to how a credit card company, such as Visa or MasterCard, functions: The rewards to card holders are analogous in our example to the return of some of the 1 % fee to the club members, with the buyers who use debit or cash being analogous to the non-club members.

We do not want to get into a debate as to whether this behavior on the part of the credit card companies can be justified on the basis of the benefits that the card company creates for the firms that accept its card.Footnote 19 Our main point is that calling something a “firm” should not immunize its actions from antitrust scrutiny if the effect of those actions is the equivalent of the formation of a coalition of agents with market power that have the ability to place a monopoly tax on others.Footnote 20 Firms can be viewed as a low-transaction cost way of organizing buyers to advantage themselves at the expense of other buyers.

4.3 Standard-Setting Organizations

One of the clearest examples of viewing antitrust through the lens of formation of coalitions is to focus on standard-setting organizations (SSOs). An SSO is an institution, the express purpose of which is to allow the formation of coalitions that agree upon and promulgate standards. A typical SSO can consist of industry members that include both creators of intellectual property and users of intellectual property. The SSO, for example, can define the characteristics that every smartphone must meet in order to be “standard compliant.” Failure to be “standard compliant” can mean zero sales.

The owner of a patent, the functionality of which is incorporated in the standard, is said to have a “standard essential patent” (SEP). The incorporation of patented functionality into a standard may confer additional market power on the owner of the SEP when (prior to the setting of the standard) there were competing producer/owners of similar functionalities, any one of which may have sufficed to create a useful alternative standard. Once the standard is set, each manufacturer of a standard compliant product must pay a royalty to the patent owner or be subject to a patent infringement suit.

The owner of a SEP does not typically commit ex ante to any particular royalty rate for its patent when used pursuant to the standard. The obvious antitrust concern is that the owner of the SEP can demand high royalties because its patent has been incorporated into a standard (and there is “lock-in”: the ex post transaction costs of substituting one of the ex-ante similar functionalities are relatively high).

To address this antitrust concern, SSOs typically require their members to agree to charge fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) rates. There has been significant litigation about what these terms mean; but the main point that we wish to emphasize here is that this is a problem of coalition formation.

For a patented feature to be voted into a standard, the SSO must reach some consensus among current members to include it. Let’s suppose that there are two substitutable patents either of which could, ex ante, be included in the standard to produce equally valuable standards. Suppose the existing manufacturers go to inventor 1 and say “we will vote you as the standard, provided you charge us a low royalty. Moreover, for later entrants who will compete against us, you must charge them a high royalty rate. In other words, we will grant you market power that you can exploit against our future (currently non-voting) rivals and consumers, and by charging us a low rate you will be sharing some of those profits with us.”

The key point to notice is that if future rivals are not members of the SSO or not important members, this is a way in which it is easy to form a coalition to raise rivals’ costs. Even if there is no explicit agreement about what the ex ante royalty rate will be, so long as it is understood that the royalty rate will be higher for later entrants, this arrangement can succeed in allowing a consortium of manufacturers and a patent holder to exploit future consumers (that likely also are not well-represented in the SSO).

It is possible to prevent this type of antitrust problem by interpreting the “ND” (non-discriminatory) part of FRAND in a particular way: If “ND” is interpreted to mean that all manufacturers should be treated similarly if they are “similar,” then—so long as one interprets current and subsequent entrants to be “similarly situated”—this particular exercise of market power is avoided.Footnote 21

The beauty of the example of the standard-setting organization is that it starkly shows that coalitions are needed both to pass the standard and to exploit others. The exploiting coalition can consist of manufacturers, holders of intellectual property, and some consumers, while the victims of the exploitation can be future entrants and some consumers.

5 Conclusion

In a world of no transaction costs, the usual justifications for antitrust policy as a way to avoid the inefficiencies from market power disappear. In the more realistic setting of transaction costs, an antitrust analysis must pay attention to whether nonlinear pricing is used and, if so, how its use alters the antitrust analysis from the usual one that assumes uniform pricing.

Industry practices and market structure can affect the ability to use nonlinear pricing. When that ability is present, it can be misleading to ignore that ability and to act as if there is uniform pricing. Especially when mergers generate large production efficiencies and when the merged firm can move from uniform pricing to nonlinear pricing, the standard analysis can give the wrong answer about whether a particular merger is desirable.

More generally, when one examines those situations where the cost of forming coalitions is high or low, one can gain insight into when market power is likely to occur. By focusing on coalitions that include more than just firms, one can gain some insight into understanding conduct that has raised antitrust concerns in exclusive dealing, credit cards, and standard setting organizations.

Notes

Or, more precisely, the efficient solution is one that takes account of transaction costs and depends on the efficient assignment of property rights. Stigler, only half-jokingly, described Coase’s article and in particular his first result—the one involving no transaction costs—as 60 pages of Pareto-optimality said very slowly. Stigler’s point is that since a bigger pie is always preferred to a smaller one, Coase’s point is obvious if one defines “no transaction costs” to mean that one obtains efficiency. [Stigler would be the first to admit that Coase’s point was not, at least initially, obvious to anyone; see Stigler (2003).]

One example of this might be the vertical integration of a content provider into satellite distribution. Other competitors to the satellite provider such as cable companies might complain about the possible foreclosure of desirable program content. But then the relevant question is: Why is this foreclosure easier post-merger than pre-merger, especially in an industry where exclusionary contracts are not unusual? See, for example, the report of Carlton et al. (2003) that is related to News Corp’s acquisition of DirecTV where Carlton appeared as an expert for News Corp., as well as the testimony of Carlton (2014) with regard to the proposed merger of Comcast and Time Warner.

The US antitrust authorities can act to prevent a harm to competition. The FCC can act if their action is “in the public interest.”

Once some of the gains from the merger are split between the merging firm and its largest buyer, it becomes unclear what possible theoretical justification there is for focusing on consumer surplus rather than total surplus in formulating antitrust policy.

We note that almost every merger likely makes some consumers worse off. Think of an airline merger where post-merger the firm moves a plane from a low demand route to a high demand route. The consumers on the low demand route may be harmed. Yet, we suspect that the Department of Justice would not block such a merger solely for that reason.

This example does not violate the “one monopoly profit” theorem. Instead, it illustrates that when there is the ability of the input monopolist to create an output monopoly that can price discriminate, this will lead to higher profits than if the output market is characterized by uniform pricing. One can view the example as the creation by the input monopolist of the transaction technology to allow the output monopolist to price discriminate.

Of course, those downstream consumers would, following Coase, want to eliminate the deadweight loss, and could pay to undo this arrangement. To keep it simple, we will assume that such arrangements engender such high transaction costs as to eliminate their feasibility.

This is a variant on a well-understood motive for a monopolist to integrate vertically downstream into an otherwise competitive industry: The monopolist may be able profitably to practice downstream price discrimination or other forms of nonlinear pricing in a way that the competitive firms could not.

Gowrisankaran et al. (2015) is a notable exception.

We fully understand that one could adopt more complicated pricing schemes than two-part tariffs—indeed the logic of the previous section suggests that one should explain, not assume, why such complicated schemes are not being used. But since our main point is to illustrate the implications of altering the assumptions of uniform pricing, our approach suffices to make our point.

See Carlton and Keating (forthcoming) for details.

The notion that it is costly to form coalitions and that cost should be a focus of study figures prominently in the literature on public choice and regulation (Olson 1965; Stigler 1971). Transaction costs have received much less attention in understanding how a firm can form as an agent for its buyers or how anticompetitive coalitions in general can form. Telser (1997) is a rare exception.

See, e.g., Tirole (1988, p. 185).

We have adhered to the standard story line of how exclusive dealing can create antitrust harm. A slight modification could be to include the cooperation of a large buyer whose presence could support new entry. Instead of sponsoring entry, the large buyer is able to obtain a low enough price so that it is effectively sharing in the monopoly profits that are created for the incumbent, by the large buyer’s unwillingness to purchase from a new entrant. Aghion and Bolton (1987) use a mechanism much like this one. See also Asker and Bar-Isaac (2014), who demonstrate that vertical restraints may be a way for the upstream monopolist to “bribe” its downstream distributors to cooperate in excluding a potential upstream rival to the monopolist.

It is frequently pointed out (correctly) that the entrant can expect to earn only duopoly profits, which limits what it is willing to bid for scarce resources (such as the loyalty of customer purchases), whereas the monopolist is trying to protect its (higher) monopoly profits (perhaps enhanced by the use of nonlinear pricing) and is thereby willing to bid higher for the scarce resources. But, again, this reverts to the transactions cost of the entrant’s efforts to capture the consumer surplus that it creates when it enters.

Selling a durable good is the equivalent of locking up a consumer’s consumption today and into the future.

There is an enormous literature now on this topic pro and con. There have been massive amounts of litigation in the US and in many foreign countries with regard to credit cards. Carlton has worked for Discover and also for plaintiffs (including government agencies) that are adverse to credit card companies. Keating has worked for major credit card companies. Because of numerous actions by regulatory and antitrust authorities, including the settlements of private litigation, the features of our example may no longer apply to credit cards in certain parts of the world.

Similar concerns can arise for, e.g., insurance companies that can act as negotiating agents for many policy holders.

References

Aghion, P., & Bolton, P. (1987). Contracts as a barrier to entry. American Economic Review, 77(3), 388–401.

Asker, J., & Bar-Isaac, H. (2014). Raising retailers’ profits: On vertical practices and the exclusion of rivals. American Economic Review, 104(2), 672–686.

Carlton, D. (2014). Declaration of Dennis W. Carlton. In the matter of applications of Comcast Corporation, Time Warner Cable Inc., Charter Communications, Inc., Time Warner Entertainment—Advance/Newhouse Partnership, and SpinCo for Consent to Assign Licenses or Transfer Control of Licensees, MB Docket No. 14-57.

Carlton, D., Halpern, J., & Bamberger, G. (2003). Economic analysis of the Newscorp/DirecTV transaction. In the matter of General Motors Corporation and Hughes Electronics Corporation, transferors and the News Corporation Limited, transferee, for authority to transfer control. MB Docket No. 03-124.

Carlton, D. W., & Perloff, J. M. (2004). Modern industrial organization (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Carlton, D. W., & Keating, B. (forthcoming). Antitrust, transaction costs and merger simulation with nonlinear pricing. Journal of Law and Economics.

Carlton, D. W., & Shampine, A. L. (2013). An economic interpretation of FRAND. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 9(3), 531–552.

Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3(1), 1–44.

Demsetz, H. (1968). The cost of transacting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82(1), 33–53.

Gilbert, R. J. (2011). Deal or no deal? Licensing negotiations in standard-setting organizations. Antitrust Law Journal, 77(3), 855–888.

Gowrisankaran, G., Nevo, A., & Town, R. (2015). Mergers when prices are negotiated: Evidence from the hospital industry. American Economic Review, 105(1), 172–203.

Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M. D., & Green, J. R. (1995). Microeconomic theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ordover, J. A., Saloner, G., & Salop, S. C. (1990). Equilibrium vertical foreclosure. American Economic Review, 80(1), 127–142.

Rasmusen, E. B., Ramseyer, J. M., & Wiley, J. S. (1991). Naked exclusion. American Economic Review, 81(5), 1137–1145.

Segal, I. R., & Whinston, M. D. (2000). Naked exclusion: Comment. American Economic Review, 90(1), 296–309.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Stigler, G. J. (2003). Memoirs of an unregulated economist (1st ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Telser, L. G. (1987). A theory of efficient cooperation and competition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Telser, L. G. (1997). Joint ventures of labor and capital. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Telser, L. G. (2006). The core theory in economics: Problems and solutions. London: Routledge.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1968). Economies as an antitrust defense: The welfare tradeoffs. American Economic Review, 58(1), 18–36.

Acknowledgments

We thank Malcolm Coate, Ken Heyer, Mark Israel, Gregory Pelnar, Sam Peltzman, Steven Salop, Chad Syverson, Lester Telser, Michael Waldman, Glenn Weyl, Larry White and Ralph Winter and participants at seminars at the FTC, the Industrial Organization Society Meetings, Northwestern University, and the University of Maryland for comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This essay is based on Carlton’s Keynote Address at the 12th Annual International Industrial Organization Conference, Chicago, IL, April 12, 2014.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlton, D.W., Keating, B. Rethinking Antitrust in the Presence of Transaction Costs: Coasian Implications. Rev Ind Organ 46, 307–321 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-015-9453-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-015-9453-4