Abstract

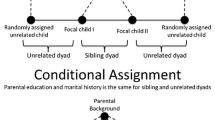

This paper analyzes peer effects among siblings in the decision to leave parental home. Estimating peer effects is challenging because of problems of reflection, endogenous group formation, and correlated unobservables. We overcome these issues using the exogenous variation in siblings’ household formation implied by the eligibility rules for a Spanish rental subsidy. Our results show that sibling effects are negative and that these effects can be explained by the presence of old or ill parents. Sibling effects turn positive for close-in-age siblings, when imitation is more likely to prevail. Our findings indicate that policy makers who aim at fostering household formation should target the household rather than the individual and combine policies for young adults with policies for the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2010, almost 60 % of young people in the 18–34 age bracket lived in their parental homes in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, whilst that statistic is below 40 % in France, the UK, and the Netherlands, and as low as 20 % in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC.

Angelini and Laferrère (2013) show that both cultural traits and the parental ability to help their children by either providing them with a home, or with a financial transfer to move out, affected the nest living patterns over time and across European countries. For an analysis on the heterogeneity of parental altruism across countries see Horioka (2014).

Children may offer caregiving activities out of altruism for their parents, or in exchange for monetary incentives offered by the family members benefiting from the services received. See Grossbard (2014) for a discussion on the motives behind caregiving.

Source: Spanish Wage Structure Survey, 2008.

Note that the policy does not generate incentives to postpone emancipation for 21 year-olds. Emancipated 21 year-olds will be entitled to the same amount of subsidy as soon as they become eligible. Aparicio and Oppedisano (2014) provide an empirical test that confirms that postponement is not significant.

Aparicio and Oppedisano (2014) show that the majority of individuals who were eligible in terms of age actually fulfilled all other criteria.

We ran our regressions omitting observations for the years after the sibling emancipated and results are very similar to those obtained when they are included. Results are available from the authors upon request.

The time frame does not include 2005 because, for individuals interviewed in 2005, we observe household formation decisions from 2006.

We also estimated all the outcomes using household and individual fixed effects and results are invariant.

Spanish newspapers documented that some regions experienced delays in processing the subsidy during the first months of its application due to lack of communication between administrative entities (El Pais, 05/02/2008).

The coefficients of the dummies for the combinations of individual’s and sibling’s gender are not identified as they are absorbed by the sibling-pair fixed effects.

The variable sibling’s education reflects the number of completed levels of education. This is, it equals 0 for siblings who did not complete any educational level, 1 for siblings who completed the first level (primary education), 2 for siblings who hold the second level diploma (secondary education) and 3 for siblings who completed the third level (tertiary education).

References

Adamopoulou, E., & Kaya, E. (2015). Young adults living with their parents and the influence of peers. Cardiff Economics Working Paper, E2015/12.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2010). The power of the family. Journal of Economic Growth, 15(2), 93–125.

Altonji, J. G., Cattan, S., & Ware, I. (2015). Identifying sibling influence on teenage substance use. Journal of Human Resources (forthcoming).

Angelucci, M., De Giorgi, G., Rangel, M., & Rasul, I. (2010). Family networks and school enrolment: Evidence from a randomized social experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 197–221.

Angelini, V., & Laferrère, A. (2013). Parental altruism and nest leaving in Europe: Evidence from a retrospective survey. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(3), 393–420.

Angrist, J. D., & Lang, K. (2004). Does school integration generate peer effects? Evidence from Boston’s Metco program. American Economic Review, 94, 1613–1634.

Aparicio, A., & Oppedisano, V. (2014). Fostering household formation: Evidence from a Spanish rental subsidy. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy. doi:10.1515/bejeap-2014-0003.

Baird, S., Bohren, A., McIntosh, C., & Ozler, B. (2014). Designing experiments to measure spillover and treshold effects. University of Pennsylvania PIER Working Paper No. 14-006.

Barr, R., & Hayne, H. (2003). It’s not what you know, it’s who you know: Older siblings facilitate imitation during infancy. International Journal of Early Years Education, 11, 7–21.

Bayer, P., Ross, S., & Topa, G. (2008). Place of work and place of residence: Informal hiring networks and labor market outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 1150–1196.

Björklund, A., Eriksson, T., Jantti, M., Raaum, O., & Osterbacka, E. (2002). Brother correlations in earnings in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden compared to the United States. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 757–772.

Björklund, A., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies. Handbook of the Economics of Education, Elsevier.

Burke, M. A., & Sass, T. R. (2013). Classroom peer effects and student achievement. Journal of Labor Economics, 31, 51–82.

Carrell, S., Malmstrom, F., & West, J. (2008). Peer effects in academic cheating. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 173–207.

Carrell, S., Sacerdote, B., & West, J. (2013). From natural variation to optimal policy? The importance of endogenous peer group formation. Econometrica, 81(3), 855–882.

Chesher, A. (2009). Single equation endogenous binary response models. Cemmap WP CWP23/09.

Chesher, A., & Rosen, A. (2013). What do instrumental variable models deliver with discrete dependent variables? The American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 103, 557–562.

Dahl, G. B., Løken, K. V., & Mogstad, M. (2014). Peer effects in program participation. American Economic Review, 104, 2049–2074.

Di Stefano, E. (2008). Leaving your mama: Why so late in Italy? University of Minnesota Working Paper.

Duflo, E., & Saez, E. (2003). The role of information and social interactions in retirement plan decisions: Evidence from randomized experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 815–842.

Gaviria, A., & Raphael, S. (2001). School-based peer effects and juvenile behavior. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83, 257–268.

Grossbard, S. (2014). A note on altruism and caregiving in the family: Do prices matter? Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 487–491.

Hensvik, L., & Nilsson, P. (2010). Businesses, buddies and babies: social ties and fertility at work. IFAU-Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation Discussion paper.

Hesselius, P., Nilsson, P., & Johansson, P. (2009). Sick of your colleagues absence? Journal of the European Economic Association, 7, 583–594.

Horioka, C. Y. (2014). Are Americans and Indians more altruistic than the Japanese and Chinese? Evidence from a new international survey of bequest plans. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 411–437.

Hoxby, C. (2000). Peer effects in the classroom: Learning from gender and race variation. NBER Working Papers 7867, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Katz, L., Kling, J. R., & Liebman, J. B. (2001). Moving to opportunities in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 607–654.

Kuziemko, I. (2006). Is having babies contagious? Fertility peer effects between adult siblings. Princeton University Working Paper.

Lalive, R., & Cattaneo, M. (2009). Social interactions and schooling decisions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 457–477.

Lindahl, L. (2011). A comparison of family and neighborhood effects on grades, test scores, educational attainment and income—Evidence from Sweden. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 207–226.

Manacorda, M., & Moretti, E. (2006). Why do most Italian youths live with their parents? Intergenerational transfers and household structure. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4, 800–829.

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. The Review of Economic Studies, 60, 531–542.

Maurin, E., & Moschion, J. (2009). The social multiplier and labor market participation of mothers. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1, 251–272.

Mazumder, B. (2008). Sibling similarities and economic inequality in the US. Journal of Population Economics, 21, 685–701.

Mencarini, L., Meroni, E., & Pronzato, C. (2012). Leaving mum alone? The effect of parental divorce on children leaving home decisions. European Journal of Population, 28(3), 337–357.

Moffitt, R. (2001). Policy interventions, low-level equilibria, and social interactions. In S. N. Durlauf & H. Peyton Young (Eds.), Social dynamics (pp. 45–82). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nicoletti, C., & Rabe, B. (2013). Inequality in pupils’ test scores: How much do family, sibling type and neighbourhood matter? Economica, 80, 197–218.

Nicoletti, C., & Rabe, B. (2014). Sibling spillover effects in school achievement. ISER Working Paper Series 2014-40, University of Essex.

Sacerdote, B. (2001). Peer effects with random assignment: Results for Dartmouth roommates. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 681–704.

Schnitzlein, D. (2014). How important is the family? Evidence from sibling correlations in permanent earnings in the US, Germany and Denmark. Journal of Population Economics, 27, 69–89.

Solon, G., Corcoran, M., Gordon, R., & Laren, D. (1991). A longitudinal analysis of siblings correlations in economic studies. Journal of Human Resources, 26, 509–534.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank for useful suggestions Cristian Bartolucci, Alex Tetenov, Cheti Nicoletti, seminar participants at EALE conference in Turin, University College Dublin, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Freiburg University, and the Spanish Economic Association conference in Mallorca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aparicio-Fenoll, A., Oppedisano, V. Should I stay or should I go? Sibling effects in household formation. Rev Econ Household 14, 1007–1027 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9325-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9325-1