Abstract

This article examines how imbalanced sex ratios influence marriage decisions and household bargaining. Using data from the 1982 Chinese census, the traditional “availability ratio” is modified to reflect the degree to which men tend to marry women from different cohorts. This ratio reflects the average tendency of men to prefer women who are close in age to women who are several years younger than them by weighting cohort sizes using the proportion of people in the population who marry someone born in a different cohort. Given that men generally marry younger women, this ratio varies independently of the size of one’s own birth cohort. Yet, the ratio fluctuates considerably across individuals, as the sizes of birth cohorts in China vary across time and regions. This enables us to examine how variability in such ratios may influence marriage decisions and household bargaining. The findings suggest that women exercise greater bargaining power once married. Results indicate that as women become scarcer in the marriage market, they have healthier sons. Men also delay marriage, and consume less tobacco and alcohol. This paper also highlights how sensitive findings may be to using this modified weighted availability ratio rather than a traditional unweighted availability ratio.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the following studies: Coale (1984, 1991); Coale and Banister (1994); Oster (2005); Das Gupta (2005); Ebenstein (2007); Lin and Luoh (2008); Oster et al. (2008); Qian (2008); Almond et al. (2010); and Hamoudi (2010). As of 2005, China’s sex ratio at birth was 119 boys for every 100 girls. Among children ages one to four this figure rose to 125 in the overall population, reaching as high as 142 in some provinces (Zhu et al. 2009).

One consequence of declines in fertility is a "marriage squeeze" (Schoen 1983), as men generally marry women who are several years younger. Women born during periods of low fertility marry men born earlier in larger cohorts. As a result, these men are faced with a relative scarcity of women, particularly if the women they most want to marry (those generally two to three years younger) cannot be easily substituted for slightly younger cohorts, also born during low fertility periods. The largest difference in sex ratios in this article is roughly 23 %, where sex ratios range between 102 and 125. One related study has examined how a very large influx of mainland Chinese soldiers to Taiwan influenced household bargaining (Francis 2011), where the influx of Chinese soldiers raised the sex ratio for those ages 20–24 by about 57 % (from 97 men per 100 women to 152 men). While this is an important and unique study, it is unclear how generalizable the findings are beyond this particular case.

For a comprehensive survey of research studies implementing this ratio, see Chiswick and Houseworth (2011).

To illustrate this point further, while 78 % of women over 15 in China were ever married, only 70 % of men over 15 were ever married. While the total sex ratio was 1.05, the single sex ratio was 1.16. The single sex ratio by age also shows a strongly increasing pattern by age, until ages 36–40, when the single sex ratio declines.

In the 1982 Chinese census, only 10 % of women were married to men born in their same year.

Choo and Siow (2006a, 2006b) propose a static transferable utility marriage market model to demonstrate that the probability of a woman of type j marrying a husband of type i is proportional to her net gains from doing so. While their model refers to different types more generally, I define type by age here, since my focus is on people marrying across different ages.

Data was provided by the Minnesota Population Center (2006).

According to the 1982 census, the sex ratio by year of birth declines significantly for the years of the Great Famine and those immediately following. Boys born during this time period were less likely to survive to marriageable ages.

The mean age at marriage is 25 for men and 23 for women.

We would similarly estimate availability ratios from a woman’s perspective.

The sample is restricted to these years because mortality rates for men tend to increase after age 50 and men cannot legally marry when under the age of 18.

There are some limitations to this approach. First, weights determined by earlier cohorts introduce some measurement error in proxying for the weights relevant to the population under study, to the extent that these population averages differ across the two sets of cohorts. Second, these weights may be determined by some omitted socioeconomic factors which may also influence outcomes examined in the analysis here. I am grateful to a reviewer for pointing this out.

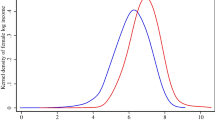

In general, distributions estimated from the two samples are quite similar. In comparison to the wider sample of men born between 1932 and 1964, men born between 1932 and 1937 are less likely to marry women closer in age, and are more likely to marry women who are increasingly younger (four to nine years younger in rural areas and three to nine years younger in urban areas).

For each bootstrap iteration, I impose the null hypothesis that the sex ratio has no effect on outcome measures. I resample residuals at the cluster level to preserve any correlation between individuals within a province and hukou type. These residuals and the covariates are then used to obtain a predicted outcome y that does not include the effect of the sex ratio. This predicted y is then regressed on the complete set of covariates that includes the sex ratio. For the ith iteration, estimates of β * 1, i , and its standard error yield corresponding Wald statistics. The distribution of these Wald statistics (under the null hypotheses) is collected over 999 iterations in order to compute critical values.

These regressions were estimated at the province-residence type-birth year level. Results are available upon request from the author.

In regressions on famine exposure averaged to the province-year-residence type level, availability ratios do not predict this measure. Results are available upon request from the author.

Results are available upon request from the author.

Results are available upon request from the author.

A detailed description of this data can be found at http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china.

According to World Bank World Development Indicators, in China, male life expectancy at birth in 2004–2008 was 71 years of age, while female life expectancy at birth was 75 years of age in 2008.

Previous regressions do not include the mother’s characteristics because they are endogenous choices made by the father.

Marriage has been virtually universal for these cohorts (Zeng 1995). According to the 1982 census, by the time men reach the age of 46–50, 96 % of them have been married, and 99 % of women in this age group have married. While nearly all eventually marry, the interest here is at what age they marry and who they marry.

A marriage matching model which incorporates these different matching characteristics and constraints may help to distinguish between these different dynamics (e.g., see Brandt et al. 2008).

Results are available upon request from the author.

References

Almond, D., Edlund, L., Li, H., & Zhang, J. (2010). Long-term effects of the 1959–1961 China famine: Mainland China and Hong Kong. In T. Ito & A. K. Rose (Eds.), The economic consequences of demographic change in East Asia. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Angrist, J. (2002). How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America’s second generation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 997–1038.

Arthur, W. B. (1994). Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Beegle, K., Frankenberg, E., & Thomas, D. (2001). Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal care and delivery in Indonesia. Studies in the Family Planning, 32(2), 130–146.

Bergstrom, T., & Bagnoli, M. (1993). Courtship as a waiting game. Journal of Political Economy, 101(1), 185–202.

Bergstrom, T., & Lam, D. A. (1994). The effects of cohort size on marriage-markets in twentieth-century Sweden. In: J. Ermisch, N. Ogawa (Eds.), The family, the market, and the state in ageing societies Reprint No. 454. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Birdsall, N., & Jamison, D. T. (1983). Income and other factors. Population and Development Review, 9(4), 51–75.

Brandt, L., Siow, A., & Vogel, C. (2008). Large shocks and small changes in the marriage market for famine born cohorts in China. Working Paper 334, Department of Economics, University of Toronto, http://www.economics.utoronto.ca/public/workingPapers/tecipa-334.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2013.

Brown, P. H. (2009). Dowry and intrahousehold bargaining: evidence from China. Journal of Human Resources, 44(1), 25–46.

Browning, M., Bourguignon, F., Chiappori, P. A., & Lechene, V. (1994). Income and outcomes: A structural model of intrahousehold allocation. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1067–1096.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 414–427.

Carolina Population Center. (2004). China Health and Nutrition Survey. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/china. Accessed 9 Dec 2013.

Chan, K. W. (2001). Recent migration in China: Patterns, trends, and policies. Asian Perspectives, 25(4), 127–155.

Chan, K. W., Liu, T., & Yang, Y. (1999). Hukou and non-hukou migrations: Comparisons and contrasts. International Journal of Population Geography, 5(6), 425–448.

Chen, Y., & Zhou, L. A. (2007). The long-term health and economic consequences of the 1959–1961 famine in China. Journal of Health Economics, 26(4), 659–681.

Chiappori, P. A., Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (2002). Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 37–72.

Chiswick, B. R., & Houseworth, C. (2011). Ethnic intermarriage among immigrants: Human capital and assortative mating. Review of Economics of the Household, 9, 149–180.

Choo, E., & Siow, A. (2006a). Estimating a marriage matching model with spillover effects. Demography, 43(3), 463–490.

Choo, E., & Siow, A. (2006b). Who marries whom and why. Journal of Political Economy, 114(1), 175–201.

Coale, A. (1984). Rapid population change in China, 1952–1982, Committee on Population and Demography Report No. 27, Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Coale, A. (1991). Excess female mortality and the balance of the sexes: An estimate of the number of `missing females’. Population and Development Review, 17, 517–523.

Coale, A., & Banister, J. (1994). Five decades of missing females in China. Demography, 31(3), 459–479.

Das Gupta, M. (2005). Explaining Asia’s ‘missing women’: A new look at the data. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 529–535.

Duflo, E. (2000). Child health and household resources in South Africa: Evidence from the old age pension program. American Economic Review, 90(2), 393–398.

Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 1–25.

Ebenstein, A. Y. (2007). Fertility choices and sex selection in Asia: Analysis and policy. http://ssrn.com/abstract=965551. Accessed 9 Dec 2013.

Fan, C. C., & Huang, Y. (1998). Waves of rural brides: Female marriage migration in China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(2), 227–251.

Fossett, M. A., & Kiecolt, K. J. (1991). A methodological review of the sex ratio: Alternatives for comparative research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 941–957.

Francis, A. (2011). Sex ratios and the Red Dragon: Using the Chinese Communist revolution to explore the effect of the sex ratio on women and children in Taiwan. Journal of Population Economics, 24, 813–837.

Goldman, N., Westoff, C. F., & Hammerslough, C. (1984). Demography of the marriage market in the United States. Population Index, 50, 5–25.

Grossbard, S., & Amuedo-Dorantes, C. (2007). Cohort-level sex ratio effects on women’s labor force participation. Review of Economics of the Household, 5, 249–278.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (1993). On the economics of marriage. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hamoudi, A. (2010). Exploring the causal machinery behind sex ratios at birth: Does Hepatitis B play a role? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(1), 1–21.

Heer, D. M., & Grossbard-Shechtman, A. (1981). The impact of the female marriage squeeze and the contraceptive revolution on sex roles and the women’s liberation movement in the United States, 1960 to 1975. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43(1), 49–65.

Huang, P., & Zhan, S. (2005). Internal migration in China: Linking it to development. Paper for Regional Conference on Migration and Development in Asia, Lanzhou, China, March 14–16, 2005.

Iyigun, M., & Walsh, R. P. (2007). Building the family nest: Premarital investments, marriage markets, and spousal allocations. Review of Economic Studies, 74(2), 507–535.

Lavely, W., Zhenyu, X., Bohua, L., & Freedman, R. (1990). The rise in female education in China: National and regional patterns. China Quarterly, 121, 61–93.

Lee, J. (2007). Marriage, the sharing rule, and pocket money: The case of South Korea. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55(3), 557–582.

Lee, D. J., & Subramanian, S. (2011). China’s successful ladies see shrinking pool of Mr. Right. Pulitzer Center, October 17, 2011, http://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/china-women-marriage-education-employment. Accessed 20 Dec 2011.

Lin, M. J., & Luoh, M. C. (2008). Can hepatitis B mothers account for the number of missing women? Evidence from three million newborns in Taiwan. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2259–2273.

Mazzocco, M. (2007). Household intertemporal behaviour: A collective characterization and a test of commitment. Review of Economic Studies, 74(3), 857–895.

Meng, X., & Qian, N. (2006). The long run health and economic consequences of famine on survivors: Evidence from China’s great famine. IZA DP No. 2471.

Minnesota Population Center. (2006). Integrated public use microdata series-international: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Mu, R., & Zhang, X. (2008). Gender difference in the long-term impact of famine. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00760. http://www.ifpri.org/pubs/dp/ifpridp00760.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2013.

Oster, E. (2005). Hepatitis B and the case of the missing women. Journal of Political Economy, 113(6), 1163–1216.

Oster, E., Chen, G., Yu, X., & Lin, W. (2008). Hepatitis B does not explain male-biased sex ratios in China. NBER Working Paper No. 13971.

Ou, J. (2011). More educated Chinese women seek foreign husbands. Straits Times, November 15, 2011, http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/Singapore/Story/STIStory_734033.html. Accessed 20 Dec 2011.

Peng, X. (1987). Demographic consequences of the great leap forward in China’s provinces. Population and Development Review, 13(4), 639–670.

Peng, X. (1989). Major determinants of China’s fertility transition. China Quarterly, 117, 1–38.

Qian, N. (2008). Missing women and the price of tea in China: The effect of sex-specific income on sex imbalance. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), 1251–1285.

Rangel, M. (2006). Alimony rights and intrahousehold allocation of resources: Evidence from Brazil. Economic Journal, 116, 627–658.

Rubalcava, L., Teruel, G., & Thomas, D. (2009). Investments, time preferences, and public transfers paid to women. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 57(3), 507–538.

Schoen, R. (1983). Measuring the tightness of a marriage squeeze. Demography, 20(1), 61–78.

The Economist. (2011). The flight from marriage. August 20, 2011.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635–664.

Thomas, D., Strauss, J., & Henriqes, M. H. (1991). How does mother’s education affect child height? Journal of Human Resources, 26(2), 183–211.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Zeng, Y. (1995). Family dynamics in China: A life-table analysis. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Zhu, W. X., Lu, L., & Hesketh, T. (2009). China’s excess males, sex selective abortion, and one child policy: Analysis of data from 2005 National Intercensus Survey. British Medical Journal, 338, b1211.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Gary Becker, Marianne Bertrand, Markus Eberhardt, Marcel Fafchamps, Soshana Grossbard, Ali Hortacsu, Steven Levitt, Albert Park, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to Douglas Almond for providing data on Great Famine death rates. I thank the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, the Oxford Martin School, the University of Chicago Center on Aging, and the Chicago Center for Excellence in Health Promotion Economics for providing financial support for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Porter, M. How do sex ratios in China influence marriage decisions and intra-household resource allocation?. Rev Econ Household 14, 337–371 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9262-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9262-9