Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between the stock crash risk of REITs and different types of institutional investors. First, when we classify REIT institutional investors by their legal type, we find that the ownership of pension funds (bank trusts) is negatively (positively) related to REIT crash risk. In addition, the trading of investment companies, including mutual funds, has become positively related to REIT crash risk in recent years. Next, when we classify REIT institutional investors by their investment behavior, we find that REIT crash risk is positively related to the trading of transient institutional investors, which trade frequently to maximize short-term gains. Moreover, the adverse impact of transient investors on REIT crash risk has worsened recently. These findings highlight the heterogeneous impacts of different types of institutional investors on REIT crash risk, which has important implications for REIT market participants and policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The market capitalization data are from www.REIT.com, the website of the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT).

For details, please visit http://www.REIT.com/investing/investing-tools/REITs-sp-indexes.

McInerney et al. (2013) show that the stock market crash in 2008 increased investors’ feelings of depression and use of antidepressant drugs.

We calculate the institutional ownership of public equity REITs based on the Thomson Financial Institutional Holdings (13 F) database.

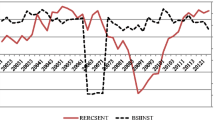

See Fig. 1 for details.

Total institutional ownership also includes university and foundation endowments, and miscellaneous institutions. Because REIT ownership by endowments is relatively small, we don’t report them separately in the paper. Similarly, we don’t report miscellaneous institutions explicitly since their exact type is unknown.

The economic significance is calculated based on the regression result reported in column 1 of Table 5.

The economic significance is calculated based on the regression result reported in column 3 of Table 5.

See Hardin and Wu (2010) in the context of REITs.

For each REIT-year observation in our sample, we select a matched non-REIT firm with the nearest market capitalization in the fiscal year from Compustat. We thank the referee for making this suggestion.

Here is a partial list of earlier studies on REIT institutional investors. Ling and Ryngaert (1997) offer evidence that the participation of institutional investors changes the dynamics of the IPO market of REITs. Chan et al. (1998) document a new trend in institutional investors’ preference for REITs. Crain et al. (2000) find that institutional investors change the pricing structure of REITs. Ciochetti et al. (2002) find that institutional investors generally prefer larger, more liquid REIT stocks. Ghosh and Sirmans (2003) find that institutional investors are not effective monitors. Chan et al. (2005) find that the Monday effect of REIT stocks disappears after institutional ownership increases. Hartzell et al. (2006) show institutional investors improve the investments decisions of REITs, which can be explained by institutional monitoring. Devos et al. (2013) examine the REIT ownership of institutional investors during the financial crisis.

We thank McKay Price for providing the REIT list. For details, please see Feng et al. (2011).

Since the accounting data are based on fiscal year, the sample period begins in fiscal year 1994 and ends in fiscal year 2011.

Because the ownership by university and foundation endowments is relatively small, we don’t report them in the paper. In addition, we don’t report miscellaneous institutions since their exact type is unknown.

The classification is based on institutional investors’ ownership stability and stake size. Ownership stability is measured by quarterly portfolio turnover and the fraction of the institution’s stocks that are held for more than two years. Stake size is measured by the average percentage ownership, the fraction of block holdings, the average dollar investment, and a Herfindahl index of ownership concentration. We thank Brian Bushee for the classification data.

We obtain quantitatively similar results when we include property returns, when we include lead and lag returns, and when we use the Fama-French three-factor model.

We compare the crash risk between REITs and non-REITs in more details in “Differences Between REITs and Non-REITs” section.

We compare the difference in institutional ownership between REITs and non-REITs in more details in “Differences Between REITs and Non-REITs” section.

When we replace ROA by funds from operations (FFO) scaled by total assets as of the previous year-end, our main results remain similar but the sample size is reduced due to missing FFO data.

According to Gillan and Starks (2007), the formation of the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) by pension funds in 1985 signifies the beginnings of shareholder activism by institutional investors. The goal of CII is “strong governance standards at public companies and strong shareholder rights”. Consisting of more than 125 public, labor, and corporate pension funds, CII pools the resources of its members and “use their proxy votes, shareowner resolutions, pressure on regulators, discussions with companies and litigation where necessary to effect change.”

The estimated coefficients of IO_BNK are significantly positive at the 5 % level in columns 3 and 7, and at the 10 % level in column 12.

As we will show later in “REIT Crash Risk and Institutional Investors in the 21st Century” section, the dynamic relationship between investment companies and REIT crash risk has changed in recent years.

Ambrose et al. (2007) examine the return comovement between REITs and general stocks after REITs join S&P indexes, and they conclude that REIT diversification power for investors has declined after the inclusion of many REITs into the broad stock indexes.

The estimated coefficient on bank trust holding becomes less significant statistically in the subsample period.

Results are not tabulated to save space, but available upon request.

References

Ambrose, B. W., Lee, D. W., & Peek, J. (2007). Comovement after Joining an Index: spillovers of nonfundamental effects. Real Estate Economics, 35, 57–90.

An, H., & Zhang, T. (2013). Stock price synchronicity, crash risk, and institutional investors. Journal of Corporate Finance, 21, 1–15.

An, H., Cook, D. O., & Zumpano, L. V. (2011). Corporate transparency and firm growth: evidence from real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics, 39, 429–454.

An, H., Hardin, W. G., III, & Wu, Z. (2012). Information asymmetry and corporate liquidity management: evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 45, 678–704.

Bogle, J. C. (2009). The fiduciary principle: no man can serve two masters. Journal of Portfolio Management, 36, 15–25.

Brickley, J., Lease, R., & Smith, C. (1988). Ownership structure and voting on antitakeover amendments. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 267–291.

Bushee, B. J. (1998). The influence of institutional investors on myopic R and D investment behavior. Accounting Review, 73, 305–333.

Bushee, B. J. (2001). Do institutional investors prefer near‐term earnings over long‐run value? Contemporary Accounting Research, 18, 207–246.

Bushee, B. J. (2004). Identifying and attracting the “Right” investors: evidence on the behavior of institutional investors. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 16, 28–35.

Callen, J. L., & Fang, X. (2013). Institutional investor stability and crash risk: monitoring versus short-termism? Journal of Banking and Finance, 37, 3047–3063.

Chan, S., Leung, W., & Wang, K. (1998). Institutional Investment in REITs: Evidence and Implications. Journal of Real Estate Research, 16, 357–374.

Chan, S., Leung, W., & Wang, K. (2005). Changes in REIT structure and stock performance: evidence from the monday stock anomaly. Real Estate Economics, 33, 89–121.

Chen, J., Hong, H., & Stein, J. C. (2001). Forecasting crashes: trading volume, past returns, and conditional skewness in stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 61, 345–381.

Chung, R., Fung, S., & Hung, S. Y. K. (2012). Institutional investors and firm efficiency of real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 45, 171–211.

Ciochetti, B. A., Craft, T. M., & Shilling, J. D. (2002). Institutional investors’ preferences for REIT stocks. Real Estate Economics, 30, 567–593.

Crain, J., Cudd, M., & Brown, C. L. (2000). The impact of the Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1993 on the pricing structure of equity REITs. Journal of Real Estate Research, 19, 275–285.

Devos, E., Ong, S. E., Spieler, A. C., & Tsang, D. (2013). REIT institutional ownership dynamics and the financial crisis. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 47, 266–288.

Downs, D. (1998). The value in targeting institutional investors: evidence from the five-or-fewer rule change. Real Estate Economics, 26, 613–616.

Feng, Z., Ghosh, C., He, F., & Sirmans, C. (2010). Institutional monitoring and REIT CEO compensation. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 40, 446–479.

Feng, Z., Price, S. M., & Sirmans, C. (2011). An overview of equity real estate investment trusts (REITs): 1993–2009. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 19, 307–343.

Ghosh, C., & Sirmans, C. (2003). Board independence, ownership structure and performance: evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 26, 287–318.

Giambona, E., Harding, J. P., & Sirmans, C. (2008). Explaining the variation in REIT capital structure: the role of asset liquidation value. Real Estate Economics, 36, 111–137.

Gillan, S., & Starks, L. T. (2007). The evolution of shareholder activism in the United States. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 19, 55.

Hardin, W. G., III, & Hill, M. D. (2008). REIT dividend determinants: excess dividends and capital markets. Real Estate Economics, 36, 349–369.

Hardin, W. G., III, & Wu, Z. (2010). Banking relationships and REIT capital structure. Real Estate Economics, 38, 257–284.

Hartzell, J. C., Sun, L., & Titman, S. (2006). The effect of corporate governance on investment: evidence from real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics, 34, 343–376.

Hartzell, J. C., Sun, L., & Titman, S. (2014). Institutional investors as monitors of corporate diversification decisions: evidence from real estate investment trusts. Journal of Corporate Finance, 25, 61–72.

Hutton, A. P., Marcus, A. J., & Tehranian, H. (2009). Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 94, 67–86.

Jin, L., & Myers, S. C. (2006). R2 around the world: new theory and new tests. Journal of Financial Economics, 79, 257–292.

Kim, J. B., Li, Y., & Zhang, L. (2011a). CFOs versus CEOs: equity incentives and crashes. Journal of Financial Economics, 101, 713–730.

Kim, J. B., Li, Y., & Zhang, L. (2011b). Corporate tax avoidance and stock price crash risk: firm-level analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 639–662.

Ling, D. C., & Ryngaert, M. (1997). Valuation uncertainty, institutional involvement, and the underpricing of Ipos: the case of REITs. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 433–456.

McInerney, M., Mellor, J. M., & Nicholas, L. H. (2013). Recession depression: mental health effects of the 2008 stock market crash. Journal of Health Economics, 32, 1090–1104.

Wiley, J. A., & Zumpano, L. V. (2009). Institutional investment and the turn-of-the-month effect: evidence from REITs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 39, 180–201.

Acknowlegments

We are grateful to an anonymous referee, discussants and conference participants at the ARES, AREUEA, and FMA meetings. We thank McKay Price for providing the REIT list and Brian Bushee for the classification data of institutional investors. Heng An acknowledges the financial support of the Dean’s Research Scholar Fund at the Bryan School. Zhonghua Wu thanks Florida International University for research support through Hollo School of Real Estate and the Tibor and Sheila Hollo Research Fellowship. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Appendix

NCSKEW | A measure of crash risk, estimated as the negative conditional skewness of firm-specific weekly return, which is equal to the natural log of one plus the regression residua from Eq. (1). |

DUVOL | A measure of crash risk, down-to-up volatility is calculated as the log of the ratio of the standard deviation of firm-specific weekly return on up weeks to that on down weeks. |

COUNT | A measure of crash risk, calculated as the number of crashes minus the number of jumps over the fiscal year. A crash (jump) occurs when the firm-specific weekly return is 3.09 standard deviations below (above) its mean over the fiscal year. |

IO | Percentage of total institutional ownership in the REIT. For each REIT in a sample year, we first calculate the total institutional holdings by adding the shares owned by all institutional investors of that REIT based on their 13f form filings in the Thomson Financial Institutional Holdings database. We then divide the total institutional holdings by the REIT’s total number of shares outstanding obtained from CRSP. |

IO_PEN | Percentage ownership of pension funds in the REIT. |

IO_BNK | Percentage ownership of bank trusts in the REIT. |

IO_INV | Percentage ownership of investment companies in the REIT. |

IO_INS | Percentage ownership of insurance companies in the REIT. |

IO_TRA | Percentage ownership of transient institutional investors in the REIT. |

IO_DED | Percentage ownership of dedicated institutional investors in the REIT. |

ROA | Contemporaneous income before extraordinary items divided by the book value of total assets. |

RET | Average firm-specific weekly return over the fiscal year. |

MTB | Ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of equity at the end of the last fiscal year. |

SIZE | Natural log of the REIT’s market value of equity at the end of the last fiscal year. |

LEV | Book value of all liabilities scaled by total assets at the end of the last fiscal year. |

SIGMA | Standard deviation of the firm-specific weekly return over the fiscal year. |

DTURN | Detrended turnover, which is calculated as the difference between average monthly turnover over fiscal year t-1 and the prior fiscal year’s average monthly turnover. |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

An, H., Wu, Q. & Wu, Z. REIT Crash Risk and Institutional Investors. J Real Estate Finan Econ 53, 527–558 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9527-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9527-y