Abstract

Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), as espoused by Mises (1912, 1949) and Hayek (1935), predicts changes in the economy’s structure of production following an unexpected change in monetary policy. In particular, following a credit expansion the theory predicts that: previously idle resources are drawn into the market, previously employed resources are used more intensively, and prices and quantities of goods in the intermediate stages of production decline relative to the prices and quantities of goods in other stages. To test the theory’s implications we employ stage of process data which classify goods by their distance to final consumption. Using this data we run structural vector autoregressions and isolate each variable’s response to a monetary shock. Consistent with the theory, we find that resource use expands on the intensive and extensive margin. On the other hand, we find little evidence of the relative price and quantity effects predicted by ABCT. Since the relative price effects are the distinguishing aspect of ABCT, we conclude that evidence in favor of the theory is, at best, mixed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The step of identifying exogenous movements in credit and interest rates is critical to the exercise, since these variables move endogenously and hence are codetermined with other economic variables under study.

Despite this uniqueness, ABCT can be presented using theoretical constructs familiar to all economists. This is a critical contribution of Garrison (2001) and is presented in the next section.

Throughout we use “stage of production” and “stage-of-process” interchangeably to refer to a point in the structure of production. The former is used more frequently in Austrian capital theory and the latter is used by the BLS and Board.

These figures are similar to what Garrison’s (2001) presentation.

The point that overconsumption occurs in tandem with malinvestment should not be taken lightly. As Garrison (2004) notes, even Hayek exclusively focused on the malinvestment, or forced savings, aspect of monetary expansion entirely neglecting overconsumption.

The series have a sample correlation of .9481.

Note that we maintain the use of ‘crude’ and ‘intermediary’ as the middle stages of production to preserve the titles used by each dataset.

See Carilli and Dempster (2008) for example.

Johansen cointegration tests find one cointegrating relationship in the regression that includes M2.

See for instance Christiano et al. (1999).

A response is defined as statistically significant if it has the hypothesized sign the confidence interval does not contain zero.

The Romers’ data is available at a monthly frequency from 1969-1996 and is available from David Romer’s website: http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~dromer/

For examples, see Lastrapes and Selgin (1995).

References

Barro, R.J., & Gordon, D.B. (1983). Rules, discretion and reputation in a model of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(1), 101–121.

Bernanke, B., & Blinder, A. (1992). The federal funds rate and the transmission of monetary shocks. American Economic Review, 84(4), 901–922.

Blanchard, O., & Quah, D. (1989). The dynamic effects of agregate demand and supply disturbances. American Economic Review, 79(4), 655–673.

Carilli, A., & Dempster, G. (2008). Is the Austrian business cycle still relevant? The Review of Austrian Economics, 21(4), 271–281.

Christiano, L., Eichenbaum, M., Evans, C. (1999). Monetary policy shocks: what have we learned and to what end? In Handbook of Macroeconomics (Vol. 1A). Amsterdam; New York and Oxford: Elsevier Science, North-Holland.

Christiano, L., Eichenbaum, M., Evans, C. (2005) Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 1–45.

Cochran, J. (2001). Capital based macroeconomics. Recent developments and extensions of Austrian capital theory. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 4(3), 17–25.

Garrison, R. (2001). Time and money: the macroeconomics of capital structure. London: Routledge.

Garrison, R. (2004). Overconsumption and forced saving in the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle. History of Political Economy, 36(2), 323–349.

Gordon, R. (1990). The measurement of durable goods prices. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenwood, J., Hercowitz, Z., Krusell, P. (1997). Long-run implications of investment-specific technological change. American Economic Review, 87(3), 342–363.

Hayek, F.A. (1935). Prices and production. New York: Augustus M. Kelly.

Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 59(6), 1551–1580.

Keeler, J. (2001). Empirical evidence of the Austrian business cycle theory. The Review of Austrian Economics, 14(4), 331–351.

Kydland, F., & Prescott, E. (1982). Time to build and aggregate fluctuations. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(6), 1345–1370.

Lastrapes, W.D., & Selgin, G. (1995). The liquidity effect: identifying short-run interest rate dynamics using long-run restrictions. Journal of Macroeconomics, 17(3), 387–404.

Lucas, R. (1972). Expectations and the neutrality of money. Journal of Economic Theory, 4, 103–124.

Mises, L. (1953). The Theory of Money and Credit. New Haven: Yale University Press. [1912].

Mises, L. (2008). Human Action. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute. [1949].

Mulligan, R. (2002). A Hayekian analysis of the term structure of production. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 5(2), 17–33.

Mulligan, R. (2006). An empirical examination of Austrian business cycle theory. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 9(2), 69–93.

Prescott, E. (1986). Theory ahead of business cycle measurement. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 10(4), 9–22.

Romer, C., & Romer, D. (2004). A new measure of monetary policy shocks: derivations and implications. American Economic Review, 94(4), 1055–1084.

Sims, C.A. (1980). Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48(1), 1–48.

Skousen, M. (2007). The Structure of Production. New York: New York University Press.

Woodford, M. (2003). Interest and prices: foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Young, A.T. (2005). Reallocating labor to initiate changes in capital structures: Hayek revisited. Economic Letters, 89(3), 275–282.

Young, A.T. (2012). The time structure of production in the US, 2002–2009. Review of Austrian Economics, 25(2), 77–92.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors would like to thank Michael Pries and Eric Sims for their guidance, Andrew Young for open discussion, Julio Garin, William Lastrapes, William Luther, George Selgin, Mark Skousen, two anonymous referees, and the participants in the Notre Dame Macro Seminar for their useful comments.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

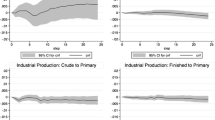

Levels Impulse Response to a 100 Basis Point FFR Shock: Timing Restriction. IRFs Represent a 100 Basis Point FFR Shock to a Five Variable VAR with 12 Lags of each Variable. Variables Include Ratios of Crude to Primary and Finished to Primary Industrial Production, as well as Crude to Intermediate and Finished to Intermediate Prices. Finally, we Proxy for Monetary Policy with the FFR. Solid Lines Display Impulse Responses to a 100 Basis Point Shock to Monetary Policy. Dashed Lines Display 80 % Confidence Intervals Generated by 1000 Bootstrap Iterations.

Levels Impulse Response to a 1 % Monetary Base Shock: Timing Restriction. IRFs Represent a 1 % Monetary Base Shock to a Five Variable VAR with 12 Lags of each Variable. Variables Include Ratios of Crude to Primary and Finished to Primary Industrial Production, as well as Crude to Intermediate and Finished to Intermediate Prices. Finally, we Proxy for Monetary Policy with the Monetary Base. Solid Lines Display Impulse Responses to a 1 % Monetary Policy Shock. Dashed Lines Display 80 % Confidence Intervals Generated by 1000 Bootstrap Iterations.

Levels Impulse Response to a 1 % M1 Shock: Timing Restriction. IRFs Represent a 1 % M1 Shock to a Five Variable VAR with 12 Lags of each Variable. Variables Include Ratios of Crude to Primary and Finished to Primary Industrial Production, as well as Crude to Intermediate and Finished to Intermediate Prices. Finally, we Proxy for Monetary Policy with M1. Solid Lines Display Impulse Responses to a 1 % Monetary Policy Shock. Dashed Lines Display 80 % Confidence Intervals Generated by 1000 Bootstrap Iterations.

Levels Impulse Response to a 1 % M2 Shock: Timing Restriction. IRFs Represent a 1 % M2 Shock to a Five Variable VAR with 12 Lags of each Variable. Variables Include Ratios of Crude to Primary and Finished to Primary Industrial Production, as well as Crude to Intermediate and Finished to Intermediate Prices. Finally, we Proxy for Monetary Policy with M2. Solid Lines Display Impulse Responses to a 1 % Monetary Policy Shock. Dashed Lines Display 80 % Confidence Intervals Generated by 1000 Bootstrap Iterations.