Abstract

The Austrian approach to business cycles has been seldom examined in econometric terms. This paper first reviews the essentials of that approach and the recent application of the Austrian business cycle theory in the economics literature. Quarterly data for Germany, USA, England and France, 1980:1 through 2006:1, are used to explore business cycle facts and relations between terms structure of interest rates, relative prices, composition of aggregate expenditure and real GDP. Results are consistent with the hypothesis of the Austrian business cycle theory that monetary policy shocks explain cycles. The changes in term structure of interest rates and composition of aggregate expenditure are large enough to explain changes in aggregate economic activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Garrison explored these two analysis ways in 2001 and 2003.

Source: Eurostat, quarterly real GDP series, real prices 1995.

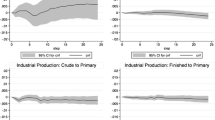

The perfect equivalence between identified business cycles and pure Austrian business cycles would require that any recession could be defined by a decline of real GDP and by a decrease of investment expenditures relative to consumption expenditures. Now, empirically, the correlation between GDP variations and investment variations is not perfect.

Source: ODCE database, quarterly series, millions of national currency.

References

Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data (3rd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Bernanke, B. (1990). On the predictive power of interest rates and interest rate spreads. New England Economic Review, pp. 51–68.

Bismans, F., & Damette, O. (2007). L’élasticité des transactions de change à la taxation: Une estimation économétrique. Document de Travail, Beta, Nancy, 34 pp.

Boettke, P. (1994). Introduction. In P. Boettke (Ed.), The Elgar companion to Austrian economics (pp. 1–6). Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Burns, A., & Mitchell, W. (1946). Measuring business cycle. New York: NBER.

Callahan, G., & Garrison, R. (2003). Does Austrian business cycle theory help explain the dot-com boom and bust? The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 6(n°2), 67–98.

Cochran, J., Call, S., & Glahe, F. (2003). Austrian business cycle theory: Variations on a theme. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 6(n°1), 67–74.

Cwik, P. (1998). The recession of 1990: A comment. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 1(n°2), 85–88.

Garrison, R. (1991). New Classical and Old Austrian economics: Equilibrium business cycle theory in perspective. The Review of Austrian Economics, 5(n°1), 91–103.

Garrison, R. (2001). Time and money: The macroeconomics of capital structure. London: Routledge.

Hadri, K. (2000). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panel data. Econometrics Journal, 3, 148–161.

Hayek, F. (1931). Price and production. New York: Augustus M. Kelley (Paris, Calmann-Levy).

Hayek, F. (1937). Monetary nationalism and international stability. New York: A. M. Kelley.

Hayek, F. (1939). Profist, interest and investment and other essays on the theory of industrial fluctuations. New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Hayek, F. (1941). The pure theory of capital. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hsiao, C. (2003). Analysis of panel data. Econometric Society Monographs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hugues, A. (1997). The Recession of 1990: An Austrian explanation. The Review of Austrian Economics, 10(n°1), 107–123.

Hurlin, C., & Mignon, V. (2005). Une synthèse des tests de racine unitaire sur données de panel. Économie et prévision, 169–171, 251–295.

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Keeler, J. P. (2001). Relative prices and the business cycle. Mises Institute Working Papers.

Kydland, F., & Prescott, E. (1990). Business cycles: Real facts and a monetary myth. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Quarterly Review, 14(n°2), 3. 18.

Le Roux, P., & Levin, M. (1998). The capital structure and the business cycle: Some tests of the validity of the Austrian business cycle in South Africa. Journal for Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 22(n°3), 91–109.

Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108, 1–24.

Machlup, F. (1976). Hayek’s contribution to economics. In Essays on Hayek, Hillsdale College Press, pp. 13–59.

Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61, 653–678.

Mises, L. v. (1912). The theory of money and credit. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mises, L. v. (1936). La théorie dite autrichienne du cycle économique. Bulletin périodique de la Société Belge d’Études et d’Expansion, 35(n°103), 459–464.

Mises, L. v. (1949, 1963, 1966, (1985)). Human action. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company (édition française: Paris, Presses Universitaires de France).

Mulligan, R. (2002). A Hayekian analysis of the term structure of production. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 5(n°2), 17–33.

Mulligan, R. (2006). An empirical examination of Austrian business theory. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 9(n°2), 69–93.

Nardin, T. (2001). The philosophy of Michael Oakeshott. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

O’Driscoll, G., & Shenoy, S. (1976). Inflation, recession and stagflation. In E. G. Dolan (Ed.), The foundation of modern Austrian economics (pp. 185–211). Kansas City: Sheed and Ward.

Phillips, P. C. B. (1986). Understanding spurious regression in econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 33, 311–340.

Phillips, P. C. B., & Xiao, Z. (1998). A primer in unit root testing. Journal of Economic Surveys, 12, 423–470.

Powell, B. (2002). Explaining Japan’s recession. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 5(n°2), 35–50.

Rothbard, M. (1962). America’s Great Depression. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Salanié, B. (1999). Guide pratique des séries non stationnaires. Economie et prévision, 137, 119–137.

Sechrest, L. (2009). Evidence regarding the structure of production: An approach to Austrian business cycle theory. The Review of Austrian Economics (in press).

Sevestre, P. (2002). Econométrie des données de panels. Paris: Dunod.

Wainhouse, C. (1984). Empirical evidence for hayek’s theory of economic fluctuations. In B. Siegel (Ed.),Money in crisis (pp. 37–71). San Francisco: Pacific Institute for Public Policy Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bismans, F., Mougeot, C. Austrian business cycle theory: Empirical evidence. Rev Austrian Econ 22, 241–257 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-009-0084-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-009-0084-6