Abstract

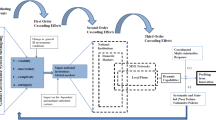

Imitation of firms that opt for strategic reorganizations by opting for mergers and acquisitions facilitates market wave formation. Empirical evidence on mergers and acquisitions suggests that, under uncertainty, firms regret more not following their rivals’ merger moves of yet unknown outcome than possibly failing jointly by copying them. Looking for the rationale for this bandwagon behavior, we explore the underlying decision-making framework by using formal logic and search for behavioral premises consistent with the observed outcomes. We point out three biased expectations, modeled by using a belief modal operator, that filter out relevant scenarios from the consideration set of otherwise rationally behaving decision-makers. The theorems derived from the logic model highlight the drive to imitate competitors’ merger choices for all but one of the eight possible outcomes of the decision-making framework. For the latter case, a boundary condition is given that makes imitation the predicted strategy. Our approach goes against the view that human behavior defies logic-based rendering also if such behavior can be adequately described as non-rational in an economic sense. Logic is a flexible representation tool to model even faulty behavior patterns in a transparent way; it can also help exploring the consequences of the cognitive mistakes made. Our findings suggest that threats to wealth creation may not necessarily find their origins in morally questionable organizational behavior, but rather in modalities of decision-making under uncertainty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since the literature normally does not make a distinction between merger and acquisition (or takeover), neither will we in this paper. In fact, however, mergers are rather rare, approximately only ten per cent of the total number of transactions (Schenk 2006).

The minimax regret approach is to minimize the worst-case regret and was initially developed by Savage (1951).

The literature normally calls first movers those firms that enter a new market segment first (Lieberman and Montgomery 1988; Péli and Masuch 1997). We use this concept in a broader sense: first movers are those that first utilize a new market opportunity (e.g. a hypothetical M&A advantage), or even more general, those that move first in a sequential game setting.

The formal logical representation of this latter assumption would require second-order logic (Gamut 1991b). Then, the ‘for all’ \((\forall )\) quantifier would range over the set of formulae that the model applies, while in a first-order logic (FOL) framework it can only range over variables. However, the additional formal rigor that this more sorvarphisticated logic could bring about, would not match the amount of technical and epistemic work that its introduction would take. We can still stay in a first-order frame by applying the K knowledge operator, one by one, to all pertaining premises.

Agents should first discover the consequences before believing them. This consideration brings to the problem of logical omniscience in epistemic logics. A11.1 would mean, for example, that all problems of mathematics would be solved, since mathematicians should be able to derive all theorems of their axioms. Therefore, we apply A11.1 with restraints. For example, we assume that our agents believe the consequences of simple arithmetic operations between fi and rc.

Definition # and Assumption # are abbreviated as D# and A#, respectively. The complete set of premises, including technical assumptions, listed by theorem, can be found in the Appendix under sub-heading ‘The theorems and their premises in Prover9 (FOL) format’.

References

Barnett, W.P.: The Red Queen among Organizations: How Competitiveness Evolves. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2008)

Barnett, W.P., Carroll, G.R.: Modeling internal organizational change. Ann. Rev. Soc. 21, 217–237 (1995)

Barnett, W.P., Pontikes, E.G.: The Red Queen, success bias, and organizational inertia. Manag. Sci. 54, 1237–1251 (2008)

Barnett, W.P., Sorenson, O.: The Red Queen in organizational creation and development. Ind. Corp. Change 11, 89–325 (2002)

Bikker, J.A., Haaf, K.: Competition, concentration and their relationship: an empirical analysis of the banking industry. J. Bank. Finac. 26, 2191–2214 (2002)

Boone, C., Hendriks, W.: Top management team diversity and firm performance: moderators of functional-background and locus-of-control diversity. Manag. Sci. 55, 165–180 (2009)

Bruggeman, J.P., Vermeulen, I.: A logical toolkit for theory (re)construction. Soc. Methodol. 32, 183–217 (2002)

DiMaggio, P.J., Powell, W.W.: The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorrvarphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Soc. Rev. 48, 147–160 (1983)

Gamut, L.T.F.: Logic, Language and Meaning, Volume 1: Introduction to Logic. Chicago University Press, Chicago (1991)

Gamut, L.T.F.: Logic, Language and Meaning, Volume 2: Intensional Logic and Logical Grammar. Chicago University Press, Chicago (1991)

Granovetter, M.: Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Soc. 83, 1420–1443 (1978)

Gugler, K., Mueller, D.C., Yurtoglu, B.B.: The determinants of merger waves. Research paper, Utrecht University, School of Economics (2005)

Hambrick, D.C.: Upper echelons theory: an update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32, 334–343 (2007)

Hannan, M.T., Freeman, J.: Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Soc. Rev. 49, 149–164 (1984)

Hart, S., Mas-Colell, A.: Continuous regret-based dynamics. Games Econ. Behav. 45, 375–394 (2003)

Herzig, A., Longin, D.: On modal probability and belief. In: Carbonell, J.G., Siekmann, J. (eds.) Symbolic and Quantitative Approaches to Reasoning with Uncertainty. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 62–73. Springer, Berlin (2003)

Hiller, N.J., Hambrick, D.C.: Conceptualizing executive hubris: the role of (hyper) core self-evaluations in strategic decision-making. Strat. Manag. J. 26, 297–319 (2005)

Kamps, J., Pólos, L.: Reducing uncertainty: a formal theory of ‘Organizations in action’. Am. J. Soc. 104, 1774–1810 (1999)

Kuilman, J., Vermeulen, I., Li, J.: The consequents of organizer ecologies: a logical formalization. Ac. Manag. Rev. 34, 253–272 (2009)

Lakatos, I.: Proofs and Refutations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1976)

Lane, C., Bachmann, R. (eds.): Trust Within and Between Organizations: Conceptual Issues and Empirical Application. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1998)

Lieberman, M.B., Montgomery, D.B.: First-mover advantages. Strat. Manag. J. 9, 41–58 (1988)

McCune, W.: Prover9 and Mace4. Theorem-prover software manual and download. http://www.cs.unm.edu/~mccune/mace4 (2011) Accessed 3 Nov 2014

Nelson, R.R., Winter, S.G.: An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Belknap Press, Cambridge (1982)

Péli, G.: Fit by founding, fit by adaptation: reconciling conflicting organization theories with logical formalization. Ac. Manag. Rev. 34, 343–360 (2009)

Péli, G., Masuch, M.: The logic of propagation strategies: axiomatizing a fragment of organizational ecology in first-order logic. Org. Sci. 8, 310–331 (1997)

Pólos, L., Hannan, M.T.: A logic for theories in flux: a model theoretic approach. Logique et Analyse 47, 85–121 (2004)

Pryor, F.L.: Dimensions of the worldwide merger boom. J. Econ. Issues 35, 825–840 (2001)

Ruef, M.: Boom and bust: the effect of entrepreneurial inertia on organizational populations. In: Baum, J.A.C., Dobrev, S.D., van Witteloostuijn, A. (eds.) Ecology and Strategy (Advances in Strategic Management, Vol. 23), pp. 29–72. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley (2006)

Thompson, J.D.: Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick (2003). [1967]

Savage, L.J.: The theory of statistical decision. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 46, 55–56 (1951)

Schenk, H.: Bandwagon mergers, international competitiveness, and government policy. Empirica 23, 255–278 (1996)

Schenk, H.: Mergers and concentration policy. In: Bianchi, P., Labory, S. (eds.) International Handbook of Industrial Policy, pp. 153–159. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (2006)

Scherer, F.M.: A new retrospective on mergers. Rev. Ind. Org. 28, 327–341 (2006)

Schlag, K., Zapechelnyuk, A.: On the impossibility of achieving no regrets in repeated games. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 81(1), 153–158 (2010). doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.09.014

Simon, H.A.: A behavioral model of rational choice. Quart. J. Econ. 69, 99–118 (1955)

Town, R.J.: Merger waves and the structure of merger and acquisition time-series. J. Appl. Econometr. 7, 83–100 (1992)

Veltman, F.: Defaults in update semantics. J. Phil. Logic 25, 221–261 (1996)

Van Valen, L.: A new evolutionary law. Evol. Theory 1, 517–547 (1973)

Watts, D.J.: A simple model of information cascades on random networks. PNAS 99, 5766–5771 (2002)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Tables 4, 5 and 6.

1.2 Proofs

We have justified the conclusions of the FOL core of the modal logic formalization with the online available Prover9 theorem prover. Getting to the ‘FOL core’ involved the following. First, we made two separate premise sets, one for beliefs and one for ‘state of affairs’ (which two sets can contradict). Second, we removed the modal operators from the formulae. Third, we derived by Prover9 and Mace4 the FOL versions of Theorems 1–3 from the premise set on beliefs, and Theorem 4 from the premise set on ‘state of affairs’. Fourth, we re-installed the modal operators to the formulae. The consecutive application of Axioms A11.1–4 (Table 6) to the re-unified premise set subsequently proves the modal logic versions of Theorems 1–3.

1.3 Ending the wave

How does the system get out the wave? Most likely: targets become too expensive as market values become exuberant due to explosive activity; and takeover premiums above market value increase along the wave (the number of remaining targets declines with increasing appetite), while real efficiency gains that could fuel ongoing merger behavior remain at bay. Managers gradually adjust their expectations accordingly, thus assigning a higher \(p\) subjective probability to failure than before. In model terms, \(B\) would only opt for imitation if it expects \(\textit{fi}_B > \frac{rc_B }{1 - p} \) to hold. The derivation is as follows. The condition that \(s_{1,6}\) (imitating) has higher expected relative payoff than \(s_{4,8}\) (withholding) at merger success probability \(p\) is expressed as:

This gives: \(\textit{fi}_B > \frac{rc_B }{1 - p}\). For example, for \(p = 2/3, 3/4\) and 4/5, satisfying this inequality and so opting for imitation requires that managers expect, respectively, three, four and five times higher fitness benefits than reorganization costs. So expecting high \(1-p\) failure probability is likely to block mergers beyond a threshold. Table 7 displays the relative payoff values for the general case when both fi and rc can differ for \(A\) and \(B\).

Evaporating first-mover advantages may also make \(B\) realize that benchmarking on successful practices would not likely improve its chances. In model terms, the fitness-facilitating part of belief Assumption 2 would not hold, whilst its claim on the detrimental effect of imitating bad practice would sustain. This change would allow \(B\) to perceive \(s_{2}\), but not \(s_{5}\), see Figure 2 in the main text. Comparing then \(B\)’s expected relative payoffs for the perceived \(s_{1,2,6}\) (imitation) and \(s_{4,8}\) (withholding), and as before keeping scenario probability \(p\) the same, reveals that \(B\) should believe \(\textit{fi}>6rc\) to hold for choosing imitation rather than abstaining.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Péli, G., Schenk, H. Organizational decision-maker bias supports merger wave formation: demonstration with logical formalization. Qual Quant 49, 2459–2480 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0122-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0122-8