Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of a supermajority rule on the law of 1/n, which posits that a larger number of districts increases the size of government. Our analysis suggests that supermajority rule, despite the claim that it restrains excessive spending, increases the 1/n effect, because qualified majorities require logrolling to attract additional members. Using data from US states from 1970 to 2007, we find that the adoption of a supermajority rule has a robust, worsening effect on the fiscal commons problem identified by the law of 1/n.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As legislature size increases, vote trading becomes more important to pass a spending project, leading to the approval of more projects.

The proposal for a spending project exceeding the threshold must be approved by majority of voters in a referendum.

This paper does not address the aggregation of demand within a district because supermajority rules are associated with formulation of the coalition across districts.

More general cases (\(0\,<\,\gamma\,<\,1\)) give qualitatively similar results.

The closed rule prevents amendments once a proposal has been made.

Stationarity means that each legislator takes the same action in structurally identical subgames (Baron and Ferejohn 1989; Primo 2006). A member’s continuation value equals his expected payoff in any round. Note that a more inclusive voting rule (i.e., an increase in m) reduces the size of agenda setter’s projects, thus limiting the tendency for the agenda setter to exploit other coalition members.

Note that \(z (p V) = \underset{z}{{\text {{argmax}}}} [u(z) - m \cdot (p/n) \cdot z]\), where \(u(\cdot )\) is the value of z to coalition members. In the standard formulation of the law of 1/n, \(z (p/n) = \underset{z}{{{\text {argmax}}}} [u(z) - (p/n) \cdot z]\).

More generally, E can be written as \(p \cdot m^{\gamma } \cdot z (p V)\), which implies that \(E_n = \gamma \cdot p \cdot n^{\gamma - 1} \cdot V^{\gamma } \cdot z (p V)\).

If \(\gamma = 0\), E can be written as \(p \cdot z (p V)\), from which \(E_n = 0\) given V.

Primo (2006) finding is partially driven by the assumption that costs of projects are convex.

The issue of multicollinearity involving \(S_{it}\) and \(N_{it}\) is ignored because the correlations between the two variables are low (−0.08 for lower chambers and −0.18 for upper chambers).

Only Nebraska has a unicameral structure.

Supermajority states typically adopted the rules in 10-year waves.

Total revenue is treated the same as expenditure because most American states have balanced budget requirements and cannot expect a bailout from the federal government (McKinnon and Nechyba 1997). Note that many state governments finance capital spending (e.g., schools and highways) by issuing bonds, and that only the interest payments on those bonds appear in the public budget.

Dropping the population variable did not affect the results.

The marginal effects are based on the estimation results in (5) and (6).

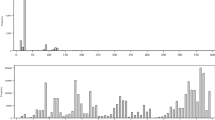

Data refer to the average values for the 1970–2007 period.

Calculation is based on the results in column (7).

Regression outputs used to calculate the marginal effects are available upon request to the author.

This intuition is based on Ansolabehere et al. (2003).

Legislators in the upper house are assumed to choose the outcome most preferred by the median voter of their constituency. We also assume that lower-house districts with equal population are completely nested within the upper-house districts. Note that in some states, boundaries of districts in the upper house and lower house cross each other.

Unequal chamber sizes in the presence of supermajority rules would add to the interest group’s problem of allocating campaign contributions and lobbying effort across the two chambers optimally.

A member’s continuation value C equals his expected payoff in any round: \((m-1)/n \times C + 1/n \times (E - (m-1)C) + (n-m)/n \times 0\). Thus, \(C = E/n\), and the agenda setter keeps \(E - (m-1) \cdot E/n\).

One way to think about this is that the agenda setter receives side payments from other coalition members—i.e., the difference between project values and continuation values.

Note that the net benefits for a legislator in district i are \(u(z_{i}) - (z_{1} + z_{2} + ... + z_{m}) \cdot p/n\). Summing this across all m coalition members gives U. By standard assumption, u is concave and increasing in \(z_{i}\).

Thus the agenda setter effectively allocates projects of size \(pV \cdot z(pV)\) to exactly \(m-1\) other coalition members, and allocates a project of size \(pV \cdot z(pV) \cdot (n - m + 1)\) to herself.

References

Ansolabehere, S., Snyder, J. M, Jr, & Ting, M. M. (2003). Bargaining in bicameral legislatures: When and why does malapportionment matter? American Political Science Review, 97(3), 471–481.

Balli, H. O., & Sørensen, B. E. (2013). Interaction effects in econometrics. Empirical Economics, 45, 583–603.

Baqir, R. (2002). Districting and government overspending. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 1318–1354.

Baron, D. P., & Ferejohn, J. A. (1989). Bargaining in legislatures. American Political Science Review, 83(4), 1181–1206.

Borcherding, T. E. (1985). The causes of government expenditure growth: A survey of the U.S. evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 28, 359–382.

Bradbury, J. C., & Crain, W. M. (2001). Legislative organization and government spending: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 82, 309–325.

Bradbury, J. C., & Johnson, J. M. (2006). Do supermajority rules limit or enhance majority tyranny? Evidence from the US States, 1960–1997. Public Choice, 127, 437–449.

Bradbury, J. C., & Stephenson, E. R. (2003). Local government structure and public expenditures. Public Choice, 115, 185–198.

Brasington, D. M. (2002). The demand for local public goods: The case of public school quality. Public Finance Review, 30(3), 163–187.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Chen, J. (2010). The effect of electoral geography on pork barreling in bicameral legislatures. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 301–322.

Chen, J., & Malhotra, N. (2007). The law of k/n: the effect of chamber size on government spending in bicameral legislatures. American Political Science Review, 101(4), 657–676.

Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3(1), 1–44.

Council of State Governments. (1970–2008). The book of the states. Lexington: Council of State Governments.

Crain, W. M., & Miller, J. (1990). Budget process and spending growth. William and Mary Law Review, 31, 1024–1046.

de Figueiredo, R. J. P. (2003). Budget institutions and political insulation: Why states adopt the item veto. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2677–2701.

Egger, P., & Koethenbuerger, M. (2010). Government spending and legislative organization: Quasi-experimental evidence from Germany. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(4), 200–212.

Gabel, M. J., & Hager, G. L. (2000). How to succeed at increasing spending without really trying: The balanced budget amendment and the item veto. Public Choice, 102, 19–23.

Gilligan, T. W., & Matsusaka, J. G. (1995). Deviations from constituent interests: The role of legislative structure and political parties in the states. Economic Inquiry, 33(3), 383–401.

Gilligan, T. W., & Matsusaka, J. G. (2001). Fiscal policy, legislative size, and political parties: Evidence from state and local governments in the first half of the 20th century. National Tax Journal, 54(1), 57–82.

Harrington, J. E. (1990). The power of the propsal maker in a model of endogenous agenda formation. Public Choice, 64, 1–20.

Holsey, C. M., & Borcherding, T. E. (1997). Why does government’s share of national income grow? An assessment of the recent literature on the U.S. experience. In D. C. Mueller (Ed.), Perspectives on public choice (pp. 562–589). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inman, R. P., & Fitts, M. A. (1990). Political institutions and fiscal policy: Evidence from the U.S. historical record. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 6, 79–132.

Jordahl, H., & Liang, C.-Y. (2010). Merged municipalities, higehr debt: On free-riding and the common pool problem in politics. Public Choice, 143, 157–172.

Knight, B. G. (2000). Supermajority voting requirements for tax increases: Evidence from the states. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 41–67.

Lee, D., Borcherding, T. E., & Kang, Y. (2014). Public spending and paradox of supermajority rule. Southern Economic Journal, 80(3), 614–632.

Lockwood, B. (2006). Fiscal decentralization: A political economy persective. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), The handbook of fiscal federalism (pp. 33–60). Northampton: Edgar Elgar.

MacDonald, L. (2008). The impact of government structure on local public expenditures. Public Choice, 136, 457–473.

McCarty, N. M. (2000). Presidential pork: Executive veto power and distributive politics. American Political Science Review, 94, 117–129.

McCormick, R. E., & Tollison, R. D. (1981).Wealth transfers in a representative democracy. In J. M. Buchanan & G. Tullock (Eds.), Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 293–313). College Station: Taxas A&M University Press.

McKinnon, R., & Nechyba, T. (1997). Competition in federal systems: The role of political and financial constraints. In J. Ferejohn & B. R. Weingast (Eds.), New federalism: Can the states be trusted? (pp. 3–61). Stanford: The Hoover Institution Press.

Oates, W. C. (1996). Estimating the demand for public goods: The collective choice and contingent valuation approaches. In D. Bjornstad & J. Kahn (Eds.), The contingent valuation of environmental resources (pp. 211–230). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Oates, W.C. (2006). On the theory and practice of fiscal decentralization. IFIR Working Paper No. 2006–05.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Perotti, R., & Kontopoulos, Y. (2002). Fragmented fiscal policy. Journal of Public Economics, 86, 191–222.

Petterson-Lidbom, P. (2012). Does the size of the legislature affect the size of government? Evidence from two natural experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 269–278.

Primo, D. M. (2006). Stop us before we spending again: Institutional constraints on government spending. Economics & Politics, 18, 269–297.

Primo, D. M., & Snyder, J. M. (2008). Distributive politics and the law of 1/n. Journal of Politics, 70(2), 477–486.

Raudla, R. (2010). Governing budgetary common: What can we learn from Elinor Ostrom? European Journal of Law and Economics, 30, 201–221.

Reiter, M., & Weichenrieder, A. (1997). Are public goods public? A critical survey of the demand estimates for local public services. FinanzArchiv, 54(3), 374–408.

Riker, W. H. (1962). The theory of political coalitions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schaltegger, C. A., & Feld, L. P. (2009). Do large cabinets favor large governments? Evidence on the fiscal commons problem for Swiss Contons. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 35–47.

Shaviro, D. (1997). Do deficits matter?. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Weingast, B., Shepsle, K., & Johnson, C. (1981). The political economy of benefits and costs: A neoclassical approach to distributive politics. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 642–664.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer, editors William F. Shughart II and Pete Leeson, Thomas E. Borcherding, and Sangwon Park for valuable insight and suggestions. This paper was supported by Faculty Research Fund, Sungkyunkwan University, 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In equilibrium, the agenda setter offers \(m-1\) coalition members their continuation values—i.e., E/n per member—and keeps the remaining value for herself—i.e., \(E \cdot (n-m+1)/n\).Footnote 27 In every period, the \(m-1\) members who receive an offer of E/n vote for the proposal, and all other members vote against it. The agenda setter votes for the proposal because \(E \cdot (n-m+1)/n \ge E/n\).

The bargaining outcome indicates that the agenda setter selects m district projects of total value E that will maximize her payoff. Note that the agenda setter keeps the bargaining surplus through side payments, effectively sharing in the projects of other coalition members.Footnote 28 The agenda setter thus selects district projects as if to maximize the sum of the utilities of all coalition members. Intuitively, the agenda setter maximizes the size of the pie to be divided among the coalition members. This means selecting a set of projects \((z_{1}, z_{2},...,z_{m})\) to maximize:

where \(u(z_{i})\) is the value of \(z_{i}\) to the ith coalition member.Footnote 29 The first-order conditions are \(u^{\prime } (z_{i}) = p \cdot (m/n), \forall i \in (1,...,m)\). Noting that \(p \cdot (m/n) \equiv p V\), the first-order conditions imply that \(z_{i}^{*} = z(pV)\) for all i. Since each of m legislators gets z(pV), the total government expenditures E can be written as \(p \cdot m \cdot z (p V)\).Footnote 30

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D. Supermajority rule and the law of 1/n . Public Choice 164, 251–274 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0271-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0271-x