Abstract

Coups d’etat continue to be common around the world, often leading to changes in leaders and institutions. We examine the relationship between military spending and coups and find that (i) successful coups increase military spending by more than failed attempts, and (ii) coups are more likely when military spending as a share of GDP is relatively low. Our identification strategy deals with the problem of reverse causality between coups and military spending by exploiting the conditional independence between a coup’s outcome and the change in military spending that follows it. We interpret our results as evidence that the military may stage coups in order to increase its funding, and rule out several alternative explanations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We define coups as attempts to overthrow the government by a small military coalition. As it will become clear later, coups are quite distinct from civil wars.

As part of their seminal research on leadership, Jones and Olken (2009) use the outcome of assassination attempts to estimate the impact of changes in leadership on institutions and war. They restrict their sample to cases in which a weapon was used (e.g., the gun was fired, the bomb exploded), so that the outcome of the assassination attempt can be taken as random.

We look at a number of other variables one and three years after a coup, and check whether the means differ significantly depending on the coup’s outcome. We find no significant differences across success and failure except in institutions. This suggests that other policies and outcomes do not change differentially depending on a coup’s outcome.

We have tried to follow the growth regression literature as closely as possible, and hence our use of five-year periods. By looking at a five-year interval we allow for a window during which military spending may have an effect on coups.

We also find that income measures have a significant negative relationship with coups when no fixed effects are entered, which is consistent with the literature (e.g., Londregan and Poole 1990). However, this result vanishes when we enter fixed effects.

There are a number of alternative mechanisms that could connect military spending and coups, and our findings allow us to refute a number of them (as we discuss in Sect. 6).

However, he finds that changes in military spending do not affect the probability of a coup attempt.

Tables A1–A4 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) summarize the data in more detail.

Table A5 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) shows that most coups are staged against non-democracies. However, whether a coup succeeds or fails appears to be unrelated to whether the target regime is democratic. Perhaps not surprisingly, the vast majority of successful coups lead to non-democratic regimes, while most failed coups result in the regime type remaining unchanged.

Table A6 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) shows average military spending as a percentage of GDP by country-year, separated by region and decade.

That is, it allows us to say that if one of the successful coups had instead failed, military spending would have changed as in the control group of failed coups.

We use the binary variable for democracy created by Cheibub et al. (2010). As they have argued in this journal, changes within the middle range of the Polity scale are difficult to interpret, a problem they avoid by defining a binary variable. Not all non-democracies are military regimes; for example, there are a large number of civilian autocracies.

The online Appendix can be found at http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix.

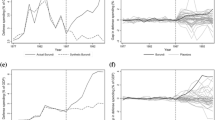

In Table A7 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) we show the results when we include coups in consecutive years. We count these coups as one event, so that the pre-coup year is the one before the first coup, and the post-coup year is the first after the last coup. We treat the event as successful if any of these coups succeeded. We also include a control variable equal to the number of years included in the event. Again we find a significant difference in the change in military spending depending on a coup’s outcome. In Table A8 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix), columns 1–4 repeat the main estimation but include data from three years before and three years after a coup. This enables us to better estimate the trends in the data, but the number of coups goes down to 80. (We cluster the standard errors to correct for serial autocorrelation, as suggested in Bertrand et al. 2004.) Once again, we find that successful coups lead to changes in military spending that are larger than the changes following failed coups. These results are significant in columns 1, 2 and 4 (and the p-value for the interaction term in column 3 is 0.11). The estimated magnitudes are similar: roughly 1 percentage point in columns 1 and 2 and over 30 % in columns 3 and 4. In columns 5–8 we allow for regional time trends, and we find that our estimates remain largely unchanged once we include these trends.

Tables A9 and A10 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) show that the effect is entirely due to changes following successful coups against non-democracies; changes in military spending following successful coups against democracies are indistinguishable from those following failed coups.

Table A11 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) replicates this table but looking at the means 3 years after a coup.

The results are similar if we shift the start of the five-year periods one year backwards or forward. The year dummies are for these seven years.

We use the binary variable for democracy created by Cheibub et al. (2010). In the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) we show that our results are robust to using the polity2 measure of democracy instead of the binary variable.

This eliminates the bias that would arise from the omission of time-invariant country-specific characteristics, which include institutions, whether the country is a primary commodity exporter (O’Kane 1987), and ethnic fractionalization (Jackman 1978). In recent years new evidence has come to light suggesting that existing cross-country correlations disappear once fixed effects are entered. For example, Acemoglu et al. (2008) show that fixed effects eliminate the observed cross-country correlation between income and democracy.

See Table A12 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) for more details.

In both cases an F-test rejects the null hypothesis that all fixed effects are equal, suggesting that they need to be included.

A surprising result is that income has no impact on coups once fixed effects are entered. It is also interesting that the size of the military and the type of regime (whether democratic or whether a military dictatorship) lose their predictive power in the presence of country fixed effects. Only instability remains significant, with its coefficient largely unchanged. There is the concern, however, that this variable is mechanically related to coups. The results are largely unaffected when this variable is removed.

The coefficients are insignificant and have a negligible impact on our estimates, while the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable introduces a number of econometric complications. For example, Nickell (1981) showed that a lagged dependent variable causes the parameter estimates to be inconsistent when fixed effects are entered.

In Table A13 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) we show that the results are robust to using the polity2 variable as a measure of democracy (instead of a binary definition). In Table A14 in the online Appendix (http://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/personal/gleon/loyalty_appendix) we repeat the estimation but separate the impact of military spending depending on whether the country is democratic or not the year before the five-year period begins.

Although it could be possible that successful coups lead to changes in policy that completely prevent these shocks, this seems unlikely.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2001). A theory of political transitions. The American Economic Review, 91, 938–963.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2005). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. The American Economic Review, 91, 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J., & Yared, P. (2008). Income and democracy. The American Economic Review, 98, 808–842.

Acemoglu, D., Ticchi, D., & Vindigni, A. (2010). A theory of military dictatorships. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(1), 1–42.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przewroski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development, 31(2), 3–36.

Banks, A. S. (2001). Cross-national time-series data archive. Binghamton: Computer Systems Unlimited.

Beeson, M. (2008). Civil-military relations in Indonesia and the Philippines: will the Thai coup prove contagious? Armed Forces and Society, 34, 474–490.

Belkin, A., & Schofer, E. (2003). Toward a structural understanding of coup risk. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 47, 594–620.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 249–275.

Besley, T., & Robinson, J. (2010). Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Civilian control over the military. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8, 655–663.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 63–101.

Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (2005). Coup traps: why does Africa have so many coups d’etat? Unpublished manuscript.

Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (2007). Military spending and the risks of coups d’etat. Unpublished manuscript.

Feaver, P. (2003). Armed servants: agency, oversight and civil-military relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Finer, S. E. (1962). The man on horseback: the role of the military in politics. London: Pall Mall Press.

Huntington, S. (1957). The soldier and the state: the theory and politics of civil-military relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Jackman, R. W. (1978). The predictability of coups d’etat: a model with African data. American Political Science Review, 72, 1262–1275.

Jones, B., & Olken, B. (2005). Do leaders matter? National leadership and growth since World War II. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 835–864.

Jones, B., & Olken, B. (2009). Hit or miss? The effect of assassinations on institutions and war. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(2), 55–87.

Lee, T. (2008). The military’s corporate interests: the main reason for intervention in Indonesia and the Philippines? Armed Forces and Society, 34, 491–502.

Leon (2013) Soldiers or politicians? Institutions, conflict and the military’s role in politics. Oxford Economic Papers. doi:10.1093/oep/gpt024.

Londregan, J., & Poole, K. (1990). Poverty, the coup trap, and the seizure of executive power. World Politics, 42, 151–183.

Londregan, J., & Poole, K. (1996). Does high income promote democracy? World Politics, 49, 1–30.

Luttwak, E. (1969). Coup d’etat: a practical handbook. New York: Knopf.

Marshall, M., & Marshall, D. R. (2010). Coup d’etat events, 1946–2009. Center for Systemic Peace.

Mbaku, J. (1991). Military expenditures and bureaucratic competition for rents. Public Choice, 17, 19–31.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49, 1417–1426.

Nordlinger, E. A. (1977). Soldiers in politics: military coups and governments. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

O’Kane, R. (1987). The likelihood of coups. Aldeshot: Avebury.

Powell, J. (2012). Determinants of the attempting and outcome of coups d’etat. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(6).

Powell, J., & Thyne, C. (2011). Global instances of coups from 1950-present. Journal of Peace Research, 48(2), 249–259.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sutter, D. (2000). A game-theoretic model of the coup d’etat. Economics and Politics, 12, 205–223.

Tullock, G. (1974). The social dilemma. Blacksburg: Center for the Study of Public Choice.

Zuk, G., & Thompson, W. R. (1982). The post-coup military spending question: a pooled cross-sectional time series analysis. American Political Science Review, 76, 60–74.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Oriana Bandiera, Tim Besley, Chris Bliss, Clare Leaver, Gilat Levy, Leandro de Maghallanes, Torsten Persson, Francis Teal and the participants at the Berkeley Center for Political Economy Workshop 2011, for their helpful comments. I kindly acknowledge the financial support of the ESRC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Appendix: Data description

Appendix A: Appendix: Data description

The main units of observation are (country, year) pairs.

- Coup::

-

This is a binary variable that is equal to 1 if at least one coup occurred, and 0 otherwise. It is taken from the dataset by Belkin and Schofer (2003), where a coup is defined as an attempt to remove the ‘regime’ by a ‘small military coalition.’ To construct their data, Belkin and Schofer (2003) compiled a list of coups from a number of academic articles, and complemented it with data from Keesing’s Contemporary Archives. They checked the accuracy of this list by consulting regional experts and resolving conflicting cases with information from the New York Times and Foreign Broadcast Information Service. More details can be found in their paper.

- Coup Success::

-

This is a binary variable that equals 1 if at least one coup was successful in the given (country, year). It is constructed by using data from Banks (2001) and Powell and Thyne (2011) to determine whether a coup was successful or not. These databases agree in all but a small number of cases, which we confirmed by looking at the New York Times Archive.

- Military Spending::

-

This variable is from the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. We compiled a number of annual reports with data on military spending, the size of the military, and some country characteristics. Our measure includes all military expenditures in the (country, year), including both operational expenses (e.g., salaries) and arms purchases. The U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency reports this data in two ways: in millions of US dollars (2000) and as a fraction of GDP.

- Size of the Military::

-

This variable is from the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. It is measured in millions.

- GDP, Population::

-

The GDP and population variables are from the World Bank Development Indicators (2009). GDP is measured in millions of US dollars (2000). Population is measured in millions.

- Democracy::

-

This variable is the ‘democracy’ variable from Cheibub et al. (2010) and it equals 1 if the regime is a democracy and 0 if it is a dictatorship. The Cheibub et al. (2010) dataset is rooted in the Alvarez et al. (1996) and Przeworski et al. (2000) datasets and shares with them the classification of regimes into just two categories: democracy and dictatorship.

- Polity2::

-

The polity2 variable is a version of the Polity IV index that has been corrected to allow for its use in time series analysis. The Polity IV index codes three key aspects of a country’s political system: (i) competitiveness and openness in the process of executive recruitment, (ii) constraints on the chief executive, and (iii) competitiveness and regulation of political participation. A weighted sum of the components is used to construct two summary variables, measuring democracy on a scale of 0 to 10 (the DEMOC score) and autocracy on a scale of −10 to 0 (the AUTOC score). The Polity IV index is the sum of these two sub-indexes.

- Military Regime::

-

This variable is constructed from the ‘regime’ variable in Cheibub et al. (2010). The regime variable can be equal to parliamentary democracy, semipresidential democracy, presidential democracy, monarchic dictatorship, military dictatorship, and civilian dictatorship. Our variable is equal to 1 if ‘regime’ equals ‘military dictatorship’, and 0 otherwise.

- Instability::

-

We use the variable S18F2 ‘Weighted Conflict Index’ from Banks (2001), which is the same used by Powell (2012). This variable is calculated by giving weights to scores on assassinations, general strikes, guerrilla warfare, government crises, purges, riots, revolutions, and anti-government demonstrations. This variable takes very large numerical values, and so in the regressions we measure it in thousands.

- Casualties::

-

This data is from the Center for Systemic Peace database by Marshall and Marshall (2010), complemented with data we collected from the New York Times Archive. We coded it as a binary variable; 0 if no deaths were reported, 1 if at least one death was reported.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leon, G. Loyalty for sale? Military spending and coups d’etat. Public Choice 159, 363–383 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0124-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0124-4