Abstract

This paper examines the determinants of total factor productivity (TFP) using a British plant-level dataset. It considers the role of the following four plant characteristics: internal and external knowledge; foreign ownership; multi-plant economies of scale and competition; and spatial spillovers and ‘place’ effects. A wide range of results are obtained, most of which confirm earlier results in the literature, such as that undertaking R&D is positively associated with TFP and most foreign ownership groups have higher than average TFP. The results also confirm the very small number of studies in the literature that have shown that the age of the plant is negatively related to TFP and therefore that vintage effects outweigh any learning-by-doing effects. The inclusion of a wide range of determinants of TFP allows comment on the relative importance of different groups of TFP determinants; knowledge creation is found to be the most important determinant of TFP (especially in manufacturing), with spatial location impacts overall the next largest determinant. Foreign-ownership is founded to be (overall) the least important determinant of TFP although this is partly the consequence of the relatively small size of the foreign-owned sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A longer version of this paper discusses these determinants in more detail. See Harris and Moffat (2014).

The notion of ‘absorptive capacity’ was initially put forward by Cohen and Levinthal (1990), who argued that the firm’s “prior related knowledge confers an ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it and apply it to commercial ends” and “these abilities collectively constitute what we call a firm’s ‘absorptive capacity’”. Thus, in simple terms, absorptive capacity is the firms’ ability to internalise external knowledge.

As Gittleman et al. (2006) show “… the correction of productivity growth for the vintage effect requires an estimate of the obsolescence and depreciation parameters on the basis of age data…(then) the use of capital stock in efficiency units does cause some smoothing of total factor productivity growth over time” (p. 306).

Martin (1993) develops a model that shows the opposite; greater competition results in a smaller payoff from increasing marginal efficiency and therefore the less it is in the interest of the owner to put in place an incentive structure that induces the manager to reduce marginal cost. Spence (1984) similarly shows that as the number of firms in the market increases (and the expected sales of each firm decreases) then the incentive to invest in cost reduction falls.

As pointed out to us by an Associate Editor, this implied relationship between competition, efficiency and profits ignores the intervening effects of economies of scope and scale. In a single-input single-output non-constant returns-to-scale production frontier, the point of maximum average product (TFP) is the point of tangency between the frontier and a ray from the origin; except in special cases like perfect competition, this is not the point of maximum profits.

For a detailed description of the ARD and discussion of several issues concerning its appropriate use, see Oulton (1997), Griffith (1999), and Harris (2002, 2005a). Analysis using the database covers a range of areas: cf. Disney et al. (2003a, b), Harris and Drinkwater (2000), Harris (2001, 2004), Collins and Harris (2002, 2005), Harris and Robinson (2002, 2003, 2004a,b), Harris and Hassaszadeh (2002), Harris et al. (2005), and Chapple et al. (2005).

For most of these industries we have no data on capital stocks, or they are only partially covered by the ARD.

More details on the UK Data service are available at http://ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/secure-access.aspx.

Note, BERD data captures firms that ‘regularly’ undertake R&D, and this could potentially underestimate R&D in smaller firms and/or those in low-tech sectors.

A major problem with the BERD is that the ONS use a different system of enterprise codes for some respondents.

We have experimented with different agglomeration and diversification measures (but note unlike the literature covered in Kominers 2008, we are not measuring whether an industry is agglomerated spatially by using an aggregated industrial agglomeration measure; rather we are trying to capture MAR-spillovers by measuring the percentage of output located in each local authority district for each 5-digit industry). With regard to agglomeration Devereux et al. (2007) used a variable measuring the number of plants in each industry in each county-year, which is significantly correlated with our measure but which we believe to be inferior (as it ignores plant size and thus the relative amount of output produced by an industry at a particular location). For diversification, there are also several different approaches, from the simple measure used by Baldwin et al. (2010) of the population size of an area, to using a locational Herfindahl index, calculated using employment shares for disaggregated industries for each area in each year, excluding a plant’s own industry (e.g. Devereux et al. 2007). These two alternative measures of diversification were strongly correlated with the one used here; the correlation with population density (we prefer this to actual population numbers to allow for the spatial size of the district) is 0.55, and with the locational Herfindahl index we had an overall correlation of 0.67 (it differs by year, but never falls below 0.48). We also believe our diversification index is ‘better’ since using 5-digit industries and 408 local authorities, the mean of the locational H-index (subtracted from 1) was 0.98 with a standard deviation of 0.012 (i.e., most local authorities are very disaggregated); our measure has a mean of 55.3 (standard deviation of 8.1)—see Table 1.

A major issue is at what level of industry disaggregation should the analysis be undertaken. To avoid the imposition of common coefficients across potentially heterogeneous industries, we have used a detailed level of disaggregation, but (as pointed out to us by a referee), such aggregation/disaggregation requires justification. We provide this in the “Appendix”.

Regions are defined as the standard administrative (or Government Office) regions. They equate to NUTS1 definitions and there are 11 regions in Great Britain.

Dividing these numbers into 1 gives the ‘numbers-equivalent’ of equal-sized firms on average operating in each sector. Note, the Herfindahl index was obtained using the following formula: Herfindahl jt = \(\sum\nolimits_{i} {\left( {y_{ij,t} /\sum\nolimits_{i} {y_{ij,t} } } \right)^{2} }\) where j refers to each 4-digit industry, i refers to a plant ∈j, t refers to year, and y refers to real gross output.

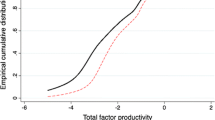

The inclusion of fixed effects is necessary as empirical evidence using plant- and firm-level panel data consistently shows that plants are heterogeneous (productivity distributions are significantly ‘spread’ out with large ‘tails’ of plants with low TFP) but more importantly that the distribution is persistent—plants typically spend long periods in the same part of the distribution. Evidence using the ARD has been presented in, for example, Haskel (2000) and more recently Martin (2008). Evidence from other countries is presented in Baily et al. (1992), Bartelsman and Dhrymes (1998). Such persistence suggests that plants have ‘fixed’ characteristics (associated with access to different path dependent (in)tangible resources, managerial and other capabilities) that change little through time, and thus need to be modelled.

In theory the production function should relate the flow of factor services to the flow of goods and services produced; in practice we rarely have data on capital and labour utilization at the micro-level, and this measurement error is included in ε it .

Using more familiar notation, TFP here is defined as A it in the standard Cobb-Douglas production function:

$$Y_{it} = A_{it} E_{it}^{{\alpha_{E} }} M_{it}^{{\alpha_{M} }} K_{it}^{{\alpha_{K} }}$$(3)and thus:

$$A_{it} = Y_{it} /(E_{it}^{{\alpha_{E} }} M_{it}^{{\alpha_{M} }} K_{it}^{{\alpha_{K} }} )$$(4)Note, lnTFP is defined here by replacing lnA it with the last term in Eq. (2). TFP is this determined by (i) the variables captured in X it (which account for plants being ‘on’ or ‘inside’ the current ‘best-practice’ technology); (ii) the time trend (which shifts the ‘best-practice’ frontier generally outwards); and (iii) plant-level fixed effects and idiosyncratic shocks captured by the error term. TFP is not affected directly by returns-to-scale \((\alpha_{E} + \alpha_{M} + \alpha_{K} )\) since any changes in the denominator on the right-hand-side of (4), as factor inputs change, is matched by changes in output, with A it unchanged.

Output, intermediate inputs, labour, capital, R&D, ‘brownfield’ FDI and competition (the Herfindahl index) are treated as endogenous. Thus lagged (predetermined) values of these variables are used as instruments and tested for in terms of their validity (see next footnote).

The validity of the instruments (i.e., that they are correlated with endogenous regressors but are not correlated with the production function error term—and hence productivity) can be tested, but system-GMM (which exploits more moments conditions than other GMM approaches) can still face the problem of weak instruments, and it is well-known by those that use the approach that the parameter estimates obtained (and the ability to pass diagnostic tests) is sensitive to the instrument set used. See also Roodman (2006) for practical guidance on applying the system-GMM approach.

The results are available in an online “Appendix”: https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/72592486/Online%20appendix.xlsx.

However, it is important to emphasize that the underlying results based on all 220 industries are very diverse.

Based on running a large number of regressions with different lags of the instruments for different endogenous variables, no general pattern on which lag-lengths should be used was found across both variables and the220 models estimated, other than lagged instruments starting from t − 4 or longer were generally needed for all endogenous variables (often longer in the case of instruments for the capital stock). In all instances the null hypothesis for the Hansen test is that the instruments used are exogenous (i.e., that they are correlated with endogenous regressors but are not correlated with the production function error term—and hence productivity); this null was accepted in all models.

Parameter estimates for dummy variables need to be converted using the formula: exp(\(\hat{\beta } - 1\)).

That is, given the persistence of heterogeneity (such that plants are expected to occupy similar positions in the distribution of TFP for long periods of time), it might be expected that relative inefficiency levels change slowly and changes in the productivity distribution are more likely in short periods to be dominated by rightward shifts caused by technical change.

The sectors were not exactly the same as those used in our study (high-tech in EU KLEMS is SIC30-33; medium high-tech is SIC29, 35-35; medium low-tech is SIC23-28; low-tech is SIC15-22, 36-37; and services comprised sectors G, H, I, SIC60-64, K and O). Note we weighted individual industry results by their share in total GVA for each year 1997-2006 to obtain the overall TFP figures reported here.

It is important to reiterate how we define ‘greenfield’ and ‘brownfield’ when modeling of TFP using Eq. (1): the former is not just for the year in which the plant begins operation, but applies throughout 1997–2008 if at any time during this period a new plant was established.

Note, the size of the plants operated by single- and multi-plant enterprises may be similar (due to internal—technical—economies of scale in production); but the size of the firm is usually larger in multi-plant enterprises. Plant size is taken into account when estimating Eq. (1) by the inclusion of factor inputs; firm size could have been entered directly as an additional variable but for single-plant enterprises this would have resulted in enterprise and plant employment being the same (and entered twice with associated multicollinearity problems). Hence we chose to include dummy variables representing whether the plant belonged to a single-plant firm, and whether it belonged to a multi-plant firm operating in more than one region.

For example, it has been argued that using competition measures such as firm-level market shares and/or price–cost margins is problematic; as Brouwer and van der Wiel (2010) show increases in competition intensity can result in the reallocation of market shares from inefficient firms (with low mark ups) to efficient firms (with high mark ups), and thus increasing mark-ups are associated with more (not less) competition. Thus we have a preference for the Herfindahl index, that includes the entire distribution of market share across firms, in the expectation that this should mitigate against (although perhaps not entirely alleviate) this problem. It is also interesting to note that Martin (2010) found a significant positive correlation between TFP and firm mark-ups (firms with higher TFP charge higher mark-ups) in Chile, although he also found that over time that when competition increased mark-ups declined as productivity distributions moved to the right.

The formula is given in the notes to Table 4; as an example, the result for the high-tech manufacturing sector is 15.9 %; i.e., 100 × [0.224 × (exp(0.105) − 1) + 0.038 + (−0.084 × ln(3.131))].

Note, this approach is preferable to the use of Chow tests because of the latter's requirements that the variance of the error term is equal across the two groups.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P (1992) A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica 60:323–351

Aghion P, Howitt P (1999) Endogenous growth theory. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Aghion P, Harris C, Howitt P, Vickers J (2001) Competition, imitation and growth with step-by-step innovation. Rev Econ Stud 68:467–492

Alexopoulos M, Nakamura AO (2011) Grappling with the elephant: a symposium on technical change and productivity. Can J Econ 44:381–386

Aoki M (1988) Information, incentives and bargaining in the Japanese economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Arrow KJ (1962) The economic implications of learning by doing. Rev Econ Stud 29:155–173

Baily MN, Hulten C, Campbell D (1992) Productivity dynamics in manufacturing plants. Brookings papers on economic activity, pp 187–249

Baldwin JR, Beckstead D, Brown WM, Rigby DL (2010) Agglomeration economies: microdata panel estimates from Canadian manufacturing. J Reg Sci 50:915–934

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17:99–120

Barney J (2001) Is the resource-based “View” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Acad Manage Rev 26:41–56

Bartelsman EJ, Dhrymes PJ (1998) Productivity dynamics: U.S. manufacturing plants, 1972–1986. J Prod Anal 9:5–34

Baumol W (1984) On productivity growth in the long run. Atlantic Econ J 12:4–10

Bernard AB, Jensen JB (2007) Firm structure, multinationals, and manufacturing plant deaths. Rev Econ Stat 89:193–204

BERR (2008) BERR’s role in raising productivity: New evidence. BERR economics paper 1. http://www.bis.gov.uk/files/file44504.pdf

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87:115–143

Brouwer E, Van Der Wiel H (2010) Competition and innovation: pushing productivity up or down? CentER discussion papers, 52, CentER, Tilburg

Buckley PJ, Casson MC (1998) Analyzing foreign market entry strategies: extending the internalization approach. J Int Bus Stud 29:539–561

Cabral LMB (2000) Introduction to industrial organization. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Campbell JR (1998) Entry, exit, embodied technology, and business cycles. Rev Econ Dyn 1:371–408

Cantwell JA, Dunning JH, Janne OEM (2004) Towards a technology-seeking explanation of U.S. direct investment in the United Kingdom. J Int Manag 10:5–20

Carlsson B, Audretsch DB, Acs ZJ (1994) Flexible technology and plant size: U.S. manufacturing and metalworking industries. Int J Ind Organ 12:359–372

Chandler AD (1962) Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the American industrial enterprise. Cambridge, MA

Chapple W, Morrison Paul CJ, Harris R (2005) Manufacturing and corporate environmental responsibility: cost implications of voluntary waste minimisation. Struct Change Econ Dyn 16:347–373

Chinitz B (1961) Contrasts in agglomeration: New York and Pittsburgh. Am Econ Rev 51:279–289

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1989) Innovation and learning: the two faces of R & D. Econ J 99:569–596

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1990) Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm Sci Q 35:128–152

Collins A, Harris R (2002) Does plant ownership affect the level of pollution abatement expenditure? Land Econ 78:171–189

Collins A, Harris R (2005) The impact of foreign ownership and efficiency on pollution abatement expenditure by chemical plants: some UK evidence. Scott J Political Econ 52:747–768

Coriat B (1995) Variety, routines and networks: the metamorphosis of fordist firms. Ind Corp Change 4:205–227

Criscuolo C, Leaver M (2006) Offshore outsourcing and productivity. OECD, Paris

Criscuolo C, Martin R, Overman H, Van Reenen J (2012) The causal effects of an industrial policy, SERC discussion papers, 98. SERC, London

Del Gatto M, Liberto AD, Petraglia C (2011) Measuring productivity. J Econ Surveys 25:952–1008

Devereux MP, Griffith R, Simpson H (2007) Firm location decisions, regional grants and agglomeration externalities. J Public Econ 91:413–435

Disney R, Haskel J, Heden Y (2003a) Entry, exit and establishment survival in UK manufacturing. J Ind Econ 51:91–112

Disney R, Haskel J, Heden Y (2003b) Restructuring and productivity growth in UK manufacturing. Econ J 113:666–694

Dixit AK, Stiglitz JE (1977) Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity. Am Econ Rev 67:297–308

Doms ME, Jensen JB (1998) Comparing wages, skills, and productivity between domestically and foreign owned manufacturing establishments in the United States. In: Baldwin RE, Lipsey R, Richardson JD (eds) Geography and ownership as bases for economic accounting. Chicago Press, Chicago

Driffield N, Love JH (2007) Linking FDI motivation and host economy productivity effects: conceptual and empirical analysis. J Int Bus Stud 38:460–473

Dunning JH (1988) Multinationals, technology and competitiveness. Unwin Hyman, London

Elhorst JP (2008) A Spatiotemporal analysis of aggregate labour force behavior by sex and age across the Europen Union. J Geogr Syst 10:167–190

Ericson R, Pakes A (1992) An alternative theory of firm and industry dynamics, Cowles foundation discussion papers, 1041. Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University, New Haven

Fosfuri A, Motta M (1999) Multinationals without Advantages. Scand J Econ 101:617–630

Fujita M, Krugman P, Venables AJ (1999) The spatial economy: cities, regions and international trade. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Gertler MS (2003) Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (There). J Econ Geogr 3:75–99

Gittleman M, ten Raa T, Wolff EN (2006) The vintage effect in TFP-growth: an analysis of the age structure of capital. Struct Change Econ Dyn 17:306–328

Griffith R (1999) Using the ARD establishment level data to look at foreign ownership and productivity in the United Kingdom. Econ J 109:F416–F442

Griffith R, Redding S, Van Reenen J (2004) Mapping the two faces of R&D: productivity growth in a panel of OECD industries. Rev Econ Stat 86:883–895

Griliches Z (1981) Market value, R&D, and patents. Econ Lett 7:183–187

Grossman GM, Helpman E (1991) Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur Econ Rev 35:517–526

Harris R (1989) The growth and structure of the UK regional economy 1963–1985. Avebury, Aldershot

Harris R (2001) Comparing regional technical efficiency in UK manufacturing plants: the case of Northern Ireland 1974–1995. Reg Stud 35:519–534

Harris R (2002) Foreign ownership and productivity in the United Kingdom—some issues when using the ARD establishment level data. Scottish J Polit Econ 49:318–335

Harris R (2004) DTI industrial support policies: key findings from new micro-data analysis. In: DTI (ed) Raising UK productivity—developing the evidence base for policy, DTI economics paper no. 8. London

Harris R (2005a) Economics of the workplace: special issue editorial. Scott J Polit Econ, 52, 323-343

Harris R (2005b) Deriving measures of plant-level capital stock in UK manufacturing, 1973–2001. Report to DTI. http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_64430_en.pdf

Harris R (2009) The effect of foreign mergers and acquisitions on UK productivity and employment. Report to UKTI. http://www.parliament.uk/deposits/depositedpapers/2010/DEP2010-0099.pdf

Harris R (2010) The impact of SDI support: inward investment 2001–2006, Report to SDI. http://workspace.imperial.ac.uk/business-school/Public/CAED/H-Harris_Inward%20Invest%20report%20for%20CAED.doc

Harris R, Drinkwater S (2000) UK plant and machinery capital stocks and plant closures. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 62:243–265

Harris R, Hassaszadeh P (2002) The impact of ownership changes and age effects on plant exits in UK manufacturing, 1974–1995. Econ Lett 75:309–317

Harris R, Li QC, Trainor M (2009) Is a higher rate of R&D tax credit a panacea for low levels of R&D in disadvantaged regions? Res Policy 38:192–205

Harris R, Moffat J (2014) Plant-level determinants of total factor productivity in Great Britain, 1997–2008 (long version). https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/72592486/TFP%201997-2008%20JPA%20revision%203%20(long%20version).pdf

Harris R, Robinson C (2002) The effect of foreign acquisitions on total factor productivity: plant-level evidence from U.K. manufacturing, 1987–1992. Rev Econ Stat 84:562–568

Harris R, Robinson C (2003) Foreign ownership and productivity in the United Kingdom estimates for UK. Manufacturing using the ARD. Rev Ind Organ 22:207–223

Harris R, Robinson C (2004a) Industrial policy in Great Britain and its effect on total factor productivity in manufacturing plants, 1990–1998. Scott J Polit Econ 51:528–543

Harris R, Robinson C (2004b) Productivity impacts and spillovers from foreign ownership in the United Kingdom. Natl Inst Econ Rev 187:58–75

Harris R, Siegel DS, Wright M (2005) Assessing the impact of management buyouts on economic efficiency: plant-level evidence from the United Kingdom. Rev Econ Stat 87:148–153

Harris R, O’Mahony M, Robinson C (2006) Research on Scottish productivity. Report to Scottish executive office of the chief economic advisor. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/919/0047033.pdf

Haskel J (2000) What raises productivity? The microeconomics of UK productivity growth, Queen Mary, University of London Research Paper, Queen Mary, University of London, London

Herfindahl O (1950) Concentration in the US steel industry, PhD Thesis, Columbia University, New York

Hermalin BE (1992) The effects of competition on executive behavior. Rand J Econ 23:350–365

Hymer S (1976) The international operations of national firms: a study of direct foreign investment. M.I.T. Press, Cambridge

Innocenti A, Labory S (2004) Outsourcing and information management: a comparative analysis of France, Italy and Japan in both small and large firms. Eur J Comp Econ 1:107–125

Jacobs J (1970) The economy of cities. Jonathan Cape, London

Jacobs J (1986) Cities and the wealth of nations. Penguin, Harmondsworth

Jarmin R (1999) Government technical assistance programs and plant survival: the role of plant ownership type. Working papers, 2. Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington

Jensen JB, McGuckin RH, Stiroh KJ (2001) The impact of vintage and survival on productivity: evidence from cohorts of U.S. manufacturing plants. Rev Econ Stat 83:323–332

Jovanovic B (1982) Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica 50:649–670

Jovanovic B, Nyarko Y (1996) Learning by doing and the choice of technology. Econometrica 64:1299–1310

Kelley MR, Harrison B (1990) The subcontracting behavior of single vs. multiplant enterprises in US manufacturing: implications for economic development. World Dev 18:1273–1294

Kominers SD (2008) Measuring agglomeration. http://www.scottkom.com/articles/measure_agglomeration.pdf

Krugman P (1997) The age of diminished expectations: U.S. economic policy in the, 1990. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Lambson VE (1991) Industry evolution with sunk costs and uncertain market conditions. Int J Ind Organ 9:171–196

Leibenstein H (1966) Allocative efficiency vs. “X-Efficiency”. Am Econ Rev 56:392–415

Levinsohn J, Petrin A (2003) Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev Econ Stud 70:317–341

Marshall A (1890) Principles of economics. Macmillan, London

Martin S (1993) Endogenous firm efficiency in a cournot principal-agent model. J Econ Theory 59:445–450

Martin R (2008) Productivity dispersion, competition and productivity measurement, CEP discussion paper, 692. Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, London

Martin R (2010) Productivity spreads, market power spreads and trade, CEP discussion paper, 997. Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, London

Mourre G (2009) What explains the differences in income and labour utilisation and drives labour and economic growth in Europe? A GDP accounting perspective. Report to directorate general economic and monetary affairs, European commission. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication13796_en.pdf

Nickell S (1996) Competition and corporate performance. J Political Econ 104:724–746

O’Mahony M, Timmer MP (2009) Output, input and productivity measures at the industry level: the EU KLEMS database. Econ J 119:F374–F403

OECD (2003) The sources of economic growth in OECD countries. http://www.oecd.org/dac/ictcd/docs/otherdocs/OtherOECD_eco_growth.pdf

Olley GS, Pakes A (1996) The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 64:1263–1297

Olsen K (2006) Productivity impacts of offshoring and outsourcing, OECD science, technology and industry working papers, 1, OECD, Paris

Oulton N (1997) The ABI respondents database: a new resource for industrial economics research. Econ Trends 528:46–57

Pakes A, Ericson R (1998) Empirical implications of alternative models of firm dynamics. J Econ Theory 79:1–45

Penrose ET (1959) The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pratten CF (1971) Economies of scale in manufacturing industries. Department of Applied Economics Occasional papers no. 28, CUP

Romer PM (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Polit Econ 94:1002–1037

Romer PM (1990) Endogenous technological change. J Polit Econ 98:S71–S102

Roodman D (2006) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to “Difference” and “System” GMM in Stata, centre for global development working paper, 103, centre for global development, Washington

Scherer FM, Beckenstein A, Kaufer E, Murphy DR, Bougeon-Massen F (1975) The economics of multi-plant operation: an international comparisons study. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Scherer FM, Ross DR (1980) Industrial market structure and economic performance. Rand McNally College Publ, Chicago

Schumpeter JA (1943) Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London

Silberston A (1972) Economies of scale in theory and practice. Econ J 82:369–391

Spence M (1984) Cost reduction, competition, and industry performance. Econometrica 52:101–121

Townroe PM, Roberts NJ (1980) Local-external economies of British manufacturing industry. Gower, Aldershot

Van Beveren I (2012) Total factor productivity estimation: a practical review. J Econ Surv 26:98–128

Van Der Panne G (2004) Agglomeration externalities: marshall versus Jacobs. J Evol Econ 14:593–604

Wernerfelt B (1984) A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg Manag J 5:171–180

Wibe S (1984) Engineering production functions: a survey. Economica 51:401–411

Zahra SA, George G (2002) Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad Manage Rev 27:185–203

Acknowledgments

This work contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown copyright and reproduced with the permission of the controller of HMSO and Queen’s Printer for Scotland. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. It was also carried out as part of an ESRC Grant (RES-591-28-0001). We would also like to acknowledge the helpful comments provided by the editors and referees, although the authors retain sole responsibility for the contents of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Disaggregation issues

While the imposition of common coefficients on industries that operate with different technologies is generally understood to be undesirable in the production function estimation literature, the appropriate level at which the data should be disaggregated is rarely tested. The approach taken in this paper is to disaggregate by 4-digit SIC industries and therefore in this section results are provided using a simple test of whether a more aggregated approach would be appropriate. Following Elhorst (2008), let A and B denote two production functions, where \(\hat{\beta }\) represents the parameters estimates and V refers to the variance–covariance, then a Wald test of the null hypothesis that the parameter estimates are the same across the two regressions is used to produce the following statistic:Footnote 35

Using the 4-digit SIC’s that belong to the high-technology manufacturing sector, Table 7 compares system-GMM regessions across pairs of industries (Tables 5, 6).

In all cases, the null of equality of coefficients is rejected at the 95 % level (there is only one pair of industries in which the null of equality of coefficients cannot be rejected at the 99 % level). This therefore provides support for our approach of estimating the models at the SIC 4-digit level.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, R., Moffat, J. Plant-level determinants of total factor productivity in Great Britain, 1997–2008. J Prod Anal 44, 1–20 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-015-0442-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-015-0442-2