Abstract

Background and Aims

Below-ground translocated carbon (C) released as rhizodeposits is an important driver for microbial mobilization of nitrogen (N) for plants. We investigated how a limited substrate supply due to reduced photoassimilation alters the allocation of recently assimilated C in plant and soil pools under legume and non-legume species.

Methods

A non-legume (Lolium perenne) and a legume (Medicago sativa) were labelled with 15N before the plants were clipped or shaded, and labelled twice with 13CO2 thereafter. Ten days after clipping and shading, the 15N and 13C in shoots, roots, soil, dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and carbon (DOC) and in microbial biomass, as well as the 13C in soil CO2 were analyzed.

Results

After clipping, about 50 % more 13C was allocated to regrowing shoots, resulting in a lower translocation to roots compared to the unclipped control. Clipping also reduced the total soil CO2 efflux under both species and the 13C recovery of soil CO2 under L. perenne. The 15N recovery increased in the shoots of M. sativa after clipping, because storage compounds were remobilized from the roots and/or the N uptake from the soil increased. After shading, the assimilated 13C was preferentially retained in the shoots of both species. This caused a decreased 13C recovery in the roots of M. sativa. Similarly, the total soil CO2 efflux under M. sativa decreased more than 50 % after shading. The 15N recovery in plant and soil pools showed that shading has no effect on the N uptake and N remobilization for L. perenne, but, the 15N recovery increased in the shoot of M. sativa.

Conclusions

The experiment showed that the dominating effect on C and N allocation after clipping is the need of C and N for shoot regrowth, whereas the dominating effect after shading is the reduced substrate supply for growth and respiration. Only slight differences could be observed between L. perenne and M. sativa in the C and N distribution after clipping or shading.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

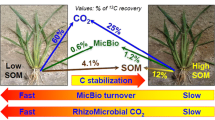

Below-ground translocation of carbon (C) by plants and its turnover are important drivers for ecological processes and functions in soil. These include nutrient availability for plants, microbe activity and turnover, or the turnover of soil organic matter (SOM) (Merbach et al. 1999; Blagodatskaya et al. 2010). The amount of C allocation by plants into the soil is affected by many factors such as plant development (Gregory and Atwell 1991; Meharg and Killham 1990), nutrient availability (Merckx et al. 1987) or plant species and plant functional groups (Warembourg et al. 2003). Since symbiotic N2 fixation requires abundant energy, legumes have a higher demand for the assimilated C for rhizosphere respiration than grasses and non-legume forbs (Phillips 1980; Vance and Heichel 1991; Warembourg et al. 2003).

For grasses, rhizodeposition is an important process affecting N availability and N uptake (Frank and Groffman 2009). Rhizodeposits enhance N mobilization by stimulating microbial activity and SOM degradation; this is termed as the ‘priming effect’ (Kuzyakov 2002). Thus, we expect that alterations in the amount of C translocated below-ground will trigger different responses in the N uptake between legumes and non-legumes.

The fast translocation of assimilates below-ground indicates a strong connection between current photosynthesis and root exudation (Gregory and Atwell 1991; Cheng et al. 1993; Kuzyakov et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2004). Hence, any change in photosynthetic activity will affect the turnover processes in the rhizosphere and thus influence N availability for plants (Kuzyakov 2002).

In this study we manipulated the photosynthetic activity by clipping or shading. After clipping (simulated grazing), photosynthesis is reduced due to a smaller leaf area (Detling et al. 1979). Clipped plants can meet their C supply for regrowth by remobilizing stored C from roots or from remaining shoot parts (Avice et al. 1996; Johansson 1993). Despite the demand for C for regrowth, root exudation after clipping was higher in many studies (Paterson and Sim 1999; 2000), however, also a reduced root exudation was found (Augustine et al. 2011). Some authors suggest that, besides C reserves, the remobilization of organic N compounds stored in roots or stubbles—such as amino acids or vegetative storage proteins—is also important for regrowth after clipping (Volenec et al. 1996).

In contrast, shading reduced the photosynthesis rate only at a lower light availability, without the removal of shoots. Like after clipping, C is preferentially allocated in above-ground plant parts after shading, as indicated by a decrease of the R:S ratio in Lolium perenne (Lambers and Posthumus 1980). Consequently, shading leads to less rhizodeposition (Hill et al. 2007). Thus, based on the different effects of clipping and shading on rhizodeposition, and based on the high demand of N for regrowth after clipping, we hypothesize that clipping enhances N uptake by plants, whereas shading reduces it.

Using repeated 13CO2 labelling of two plant species, a legume (Medicago sativa) and a non-legume plant (Lolium perenne), we investigated how a limited substrate supply after clipping and shading affected the C allocation within the plant and the below-ground C translocation. Labelling with 15NO3 - was carried out to investigate how the altered C allocation after limited assimilate supply affects N remobilization and N uptake by both plant species. The specific questions were:

-

(1)

How does a limited substrate supply affect plant biomass production and alter the distribution of C in plant, soil, microorganisms and CO2 efflux from soil?

-

(2)

How does a limited assimilate supply affect the remobilization of plant-stored N?

-

(3)

How does the effect of a limited substrate supply affect the N uptake by plants from soil?

-

(4)

Do shading and clipping induce different responses with respect to the distribution of C and N in the plant and soil pools?

Materials and methods

Soil properties and plant growing conditions

The soil used in the experiment was an arable loamy haplic Luvisol developed on loess, collected near Göttingen (Germany, 51°33´36.8´´N, 9°53´46.9´´E) from the upper 10 cm of the Ap-horizon. The basic characteristics of the soil are shown in Table 1.

The seedlings of ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) were first germinated on wet filter paper for 5 (M. sativa) and 8 days (L. perenne) and thereafter transferred to the plant pots (inner diameter 7 cm, height 20 cm), each of them filled with 700 g of air-dried, sieved (≤ 2 mm) soil. In each pot, 3 seedlings of M. sativa or 5 seedlings of L. perenne were transferred to achieve a similar biomass for both plant species. The pots were closed with a plastic lid with holes for shoots. The plants were grown at 26 to 28 °C day temperature and at 22 to 23 °C night temperature. At a day length of 14 h the light intensity was approximately 210 μmol m-2 s-1, approximately corresponding to a cumulative daily radiation in the range of field conditions. The soil moisture was maintained at 70 % of the available field capacity by daily watering with distilled water.

13C and 15N labelling

To label the soil of all pots with 15N, 16 mg of K15NO3 (enrichment: 52.7 at. %) were dissolved in water and added to the pots with the watering (28 days after planting).

The 13C labelling was conducted for the first time 50 days after planting (the day of clipping or beginning of shading). One day before 13C labelling, all pots were sealed with silicone paste (NG 3170, Thauer & Co., Dresden). All plants were labelled in a Plexiglas chamber as described by Werth and Kuzyakov (2008). Briefly, 13CO2 was introduced to the chamber by circulating air through a flask containing 150 mg of Na2 13CO3 (13C enrichment: 99.9 atm. %) for labelling of L. perenne or 15 mg of the same Na2 13CO3 for M. sativa solved in 10 ml deionized water. To produce 13CO2, an excess of 5 M H2SO4 was added to the Na2 13CO3 solution. The plants were labelled in the 13CO2 enriched atmosphere for 3 h. Before opening the labelling chamber, the chamber air was pumped through 1 M NaOH solution to remove unassimilated 13CO2. Since the amount of 13C found in the NaOH solution was negligible, it can be assumed, that all 13CO2 was assimilated. Then the chamber was opened and the trapping of CO2 evolved from the soil started. 13C labelling was repeated on day 55 after planting.

Clipping and shading

Three pots of each plant species were used for the clipping procedure or exposed to shading. Additionally, three pots of each plant species were grown under normal conditions as a control treatment. The plants were clipped or shaded 2 h before the first 13CO2 pulse. Lolium perenne shoots were clipped 4 cm above the soil surface, those of M. sativa 8 cm above the surface. Due to the different clipping heights, both plant species achieve similar stubble biomass. The clipped plants continued growth under the conditions described above. For shading, the light intensity was reduced to about 17 μmol m-2 s-1 for 10 days.

Sampling and analysis

Starting after the first labelling, the CO2 evolved from soil was trapped using a closed-circulating system. The air was pumped through tubes containing 15 ml of 1 M NaOH solution. Because of the circulation there were no losses of CO2 due to incomplete absorption by NaOH solution. The NaOH solution was changed 1, 3 and 5 days after each labelling. The pots were destructively harvested at day 60 after planting. Roots were separated from soil by handpicking. Plant and soil material was dried at 65 °C for 3 days.

To estimate total CO2 efflux, the C content of the NaOH solution was determined by titration with 0.01 M HCl against phenolphthalein after adding 1.5 M BaCl2 solution. For 13C measurements the CO2 trapped in NaOH was precipitated as SrCO3 with an excess of 0.5 M SrCl2 solution. The precipitants were centrifuged at 3800 g, washed with deionized water until the pH reached neutral conditions and dried at 65 °C.

Microbial biomass C and N was determined by the chloroform fumigation-extraction-method (CFE) (modified after Vance et al. 1987). For this, the soil was separated into two samples with 5 g each. One of these samples was firstly fumigated with chloroform for 24 h. Both samples were extracted with 20 ml of 0.05 M K2SO4, shaken for 1 h and, thereafter, centrifuged for 10 min at 3800 g. Total C and N contents of fumigated and non-fumigated soil extracts were measured using a N/C analyzer (Multi N/C 2100, AnalytikJena, Germany). The extracts of the non-fumigated samples were used to measure dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON). For the determination of 13C and 15N in the microbial biomass, DOC and DON the extracts were oven-dried at 60 °C and measured as described below.

The ground plant and soil material (ball mill), the SrCO3 and the dried extracts of the CFE were analyzed for their 13C and 15N isotope ratios. This was done using an elemental analyzer NC 2500 (CE Instruments, Milano, Italy) linked to a delta plus gas-isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) via a ConFlo III (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) interface.

Calculations and statistics

The 13C enrichment of a particular C pool (13 C excess;p ; μg g-1) was calculated as follows:

where 13 C NA;p is the 13C natural abunxdance of the respective pool (atom%), 13 C p is the amount of 13C of the pool after labelling (atom%), and C p is the total amount of C in this pool (μg g-1).

The 13C recovery in a particular C pool (13 C rec;p ; %) was calculated by dividing the amount of 13C (mg) of that particular pool (13C enrichment multiplied by the pool mass (mg)) by the sum of the 13C amount (mg) of all pools (shoot, root, soil, DOC. soil microbial biomass and soil CO2):

To determine the δ13C value of microbial biomass (δ13 C MB ; ‰) a mass balance equation was used:

where δ13 C fum (‰) and δ13 C nf (‰) are the δ13C values of the fumigated and non-fumigated samples, respectively, and C fum (mg) and C nf (mg) are the amounts of C in the fumigated and non-fumigated samples, respectively.

The calculations for 15N correspond to those for 13C.

The experiment was conducted with 3 replicates for all treatments. The values presented in the figures and tables are given as means ± standard errors of the means (±SEM). Significant differences between the treatment and the plant species were obtained by a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) in combination with a post hoc Fisher LSD test.

Results

Plant biomass production

M. sativa produced significantly more shoot biomass per plant than L. perenne during 60 days (Tab. 2). Clipping has no effects on the shoot and root biomass of M. sativa and L. perenne when measured after 10 days of regrowth (Tab. 2). Ten days of shading were also not sufficient to decrease the shoot or root biomass of both species. The R:S ratio decreased after clipping and shading of L. perenne, whereas it increased for M. sativa after clipping and slightly after shading (Tab. 2).

Effect of clipping and shading on 13C distribution in plant and soil

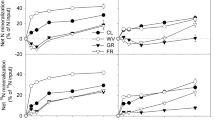

In the control treatments of L. perenne and M. sativa, about 50 % of 13C were recovered in shoots; 30 % and 20 % were found in the roots of L. perenne and M. sativa, respectively (Fig. 1). The 13C recovery in CO2 efflux, the soil, microbial biomass and DOC did not differ between both plant species (Fig. 2).

Clipping increased the 13C recovery in the shoot by about 30 % and 20 % for L. perenne and M. sativa, respectively. The retention of newly assimilated C (13C) in the shoots resulted in a lower translocation to the roots, and thus, the 13C recovery of the roots of both plant species was lower compared to the respective control (Fig. 1). However, the retention of 13C in the shoots after clipping had no effects on the 13C recovery in the soil (Fig. 2). Also, all other below-ground C pools of both plant species were not affected by clipping (Fig. 2).

Shading increased the 13C recovery in the shoots of L. perenne and M. sativa (Fig. 1). The 13C recovery was reduced only in the roots of M. sativa (Fig. 1). Like after clipping, the 13C recovery in the soil, microbial biomass and DOC was not affected by shading (Fig. 2).

Effect of clipping and shading on total CO2 and 13C efflux from soil

The total CO2 efflux from soil was significantly higher under M. sativa than under L. perenne (Fig. 3); this indicates the higher C demand in legume roots. Both treatments for reduced C assimilation decreased the CO2 efflux from soil under L. perenne. This reflects the limited substrate availability, whereby the CO2 reduction was significant only after clipping at the end of the experiment (Fig. 3). Under M. sativa, clipping and shading significantly decreased the soil CO2 efflux (Fig. 3). After clipping, however, this reduced CO2 efflux from soil lasted only until day 5. Contrary to L. perenne, the soil CO2 efflux under M. sativa was lowest after shading (Fig. 3).

Clipping also significantly reduced the 13C recovery of the soil CO2 efflux under L. perenne, because 13C was used for shoot regrowth (Fig. 2). Shading had no effect on the 13C recovery in CO2 under L. perenne. The 13C recovery of the soil CO2 efflux under M. sativa was not affected by clipping or shading (Fig. 2).

Distribution of 15N in plant and soil

Under normal light conditions a higher 15N recovery was detected for the shoots of L. perenne compared to M. sativa (Fig. 4). In the roots, the 15N recovery showed no significant differences between M. sativa and L. perenne (Fig. 4).

Clipping increased the 15N recovery only in the shoots of M. sativa, but had no effect on the 15N recovery in the roots of both plant species (Fig. 4). Also the 15N recovery in the soil, DON and microbial biomass N was unaffected by clipping (Fig. 5).

The 15N recovery in the shoots and roots of L. perenne was not affected by shading, however, it increased in the shoots of M. sativa (Fig. 4). In the soil, the DON and the microbial biomass under both plant species, shading showed no influence on the 15N recovery (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Effect of plant species

The distribution of 13C between above- and below-ground pools in the control treatment was similar for L. perenne and M. sativa, with about one half of the labelled assimilates being incorporated in the shoots (Fig. 1). This is in the range of earlier studies, reviewed by Kuzyakov and Domanski (2000). The roots of L. perenne recovered more 13C than M. sativa, whereas the portion of 13C found in the soil CO2 was higher under M. sativa (Figs. 1 and 2). A higher incorporation of assimilated C was found in the roots of the legume Trifolium repens compared to the roots of L. perenne (de Neergaard and Gorissen 2004), however, in our study there was no difference between the legume species and L. perenne. A higher total CO2 efflux from the soil was found under M. sativa compared to L. perenne, indicating a high energy need for N2 fixation.

Effect of clipping

After clipping, both species preferentially allocated 13C in the above-ground biomass as shown by an increased 13C recovery in shoots (Fig. 1). Recent studies observed an increased above-ground C allocation after clipping (Kuzyakov et al. 2002; Detling et al. 1979; Mackie-Dawson 1999). The assumption is that regrowing shoots retain photosynthates and prevent a translocation below-ground (Mackie-Dawson 1999). This agrees with our results of less 13C recovery in the roots of both plants after clipping (Fig. 1).

Especially on the first days after clipping, the remobilization of storage compounds is the major substrate supply for the regrowing shoots, including N compounds (Morvan-Bertrand et al. 1999; Ourry et al. 1988). This is confirmed by the higher post-clipping 15N recovery in the shoots of M. sativa in our study (Fig. 4). The re-translocation of root N contributes substantially to the synthesis of amino acids and proteins in the regrowing tissue of M. sativa (Avice et al. 1996). In our study there were no indications for a re-translocation of N compounds from roots to shoots of M. sativa, since there was no significant decrease of the 15N recovery in the roots. However, the design of our experiment does not allow us to make any predictions about a possible retranslocation of N which is taken up by N2 -Fixation.

It is likely that the reduced C translocation to roots has implications for root respiration and rhizodeposition, as well as for 13C incorporation in soil and availability for soil microorganisms. However, the unaffected 13C recovery in the soil shows that exudation of newly assimilated C did not change after clipping because of assimilate retention in the shoots. The increased rhizodeposition found in earlier studies (e.g. Bardgett et al. 1998) may reflect remobilization of storage compounds in roots, which would increase the release of stored C in the soil (Paterson and Sim 1999). Our 13C results, however, provide no information about the total rhizodeposition and the release of stored C. Former studies showed that an increased rhizodeposition has a positive effect on microbial activity, stimulates N cycling and thus enhances N availability for plant roots after defoliation (Guitian and Bardgett 2000; Hamilton and Frank 2001). It can be expected that this would lead to a reduced 15N recovery in the soil, however, the high variability of the results of our results makes it impossible to see these effect.

The assimilate supply is a major factor affecting root respiration (Gavrichkova et al. 2010). A reduced soil CO2 efflux after clipping, as observed for L. perenne (Fig. 3), was also found in many other studies (Detling et al. 1979; Craine et al. 1999; Kuzyakov et al. 2002). Since the 13C recovery in microbial biomass and DOC under L. perenne did not change after clipping (Fig. 2), it can be concluded that these pools were not affected by clipping. Thus, the decrease in soil CO2 can be ascribed to a reduced root respiration of current assimilates rather than reduced microbial respiration.

The soil processes under the legume M. sativa differed from those under L. perenne. The total CO2 efflux under M. sativa decreased until day 5 after clipping and, thereafter, recovered and was approximately at the same level as observed in the control pots (Fig. 3). In the same time the 13C recovery of the CO2 efflux remained. Thus, the portion of newly assimilated C in the soil CO2 is increasing after clipping. This corresponds with findings that newly assimilated C is closely related to growth respiration (Lötscher et al. 2004), which is important after clipping for the biomass production. The increasing CO2 efflux after 5 days may point to enhanced nodule respiration to restore the N2 fixation.

We conclude that high C and N demands of regrowing shoots after clipping led to a remobilization of N to the shoots and additionally, recently assimilated C was retained in the regrowing shoots.

Effect of shading

We implemented shading (besides clipping) to evaluate the effect of a limited substrate supply on the distribution of recently assimilated C and the impacts of such a limited supply on the N budget in plant and soil. In contrast to clipping, however, the effect of shading in limiting the substrate supply is not connected with the high demand for reserve C and N for shoot regrowth. The R:S ratio of L. perenne was reduced after shading (Table 2). The increased preference for shoot versus root growth is also reflected by the higher recovery of currently assimilated C (13C) in the shoots. After shading, more assimilates are allocated into the terminal meristems to compensate for the reduced photosynthesis rate (Ryle and Powell 1976). For M. sativa the 13C recovery in the shoots was very high after shading and was in the range of the clipped plants. Like after clipping, this took place at the expense of the 13C translocation into the roots, however, this is significant only for M. sativa.

Below-ground translocation of C is very closely linked to the assimilate supply (Kuzyakov and Gavrichkova 2010). Reduced soil CO2 efflux and rhizodeposition have been observed after shading (Craine et al. 1999; Hill et al. 2007). The present study indicates that the shading effect on the CO2 efflux from soil of currently assimilated C depends on the plant species.

For M. sativa the total soil CO2 efflux decreased, whereas the portion of 13C in CO2 was not influenced by shading (Figs. 2 and 3). These apparently contradictory results can be explained by the need for recently assimilated C to maintain respiration (shown by the unchanged 13C efflux) and by the reduced substrate supply (decreasing the total CO2 efflux from soil) (Kuzyakov and Cheng 2001; 2004). Contrary, for L. perenne, the total CO2 efflux and the 13C recovery in the CO2 did not change after shading.

Plants grown under normal light conditions have a higher N demand compared to shaded plants, which can be met by a higher rhizodeposition and the resulting SOM decomposition (Frank and Groffman 2009). The growth after shading is restricted by low assimilation rates (Shipley 2002), which also reduces the demand for N in the shoots. Moreover, under shaded conditions a reduced rhizodeposition causes a decreased turnover of the microbial biomass and SOM and, thus, a lower N mineralization (Zagal 1994). In our study no change of the 13C recovery in the soil of both plants and no change of the 15N recovery in the shoots of L. perenne was observed after shading. Thus, our results show no effect of shading on the rhizodeposition or the N uptake by this species. The unchanging 13C recovery at a concurrent decreasing of the total CO2 efflux underlines the importance of recently fixed C for the legume M. sativa. M. sativa uses recently fixed C for nodule respiration and stored C for root respiration (Avice et al. 1996). The decreased CO2 efflux, however, indicates overall that the nodule respiration and the root respiration were reduced. It was expected that M. sativa would remobilize storage N from roots to overcome this limitation of the N supply to shoots, since remobilization requires less energy than N fixation and can thus be an adequate mechanism to meet the N demand in the shoots (Bakken et al. 1998). The increased 15N recovery in the shoots of shaded M. sativa may be due to a reduced uptake of unlabelled N by the N2 fixation after shading. However, our results cannot clarify if the origin of the increased recovery of 15N in the shoots is the remobilization of N from roots or a higher 15N uptake from soil. Both pools show a decrease of 15N after shading, however for both this decrease was not significant.

We conclude that shading has a pronounced effect on the below-ground allocation of currently assimilated C for both plant species; on the other hand shading has effects on the N distribution only for M. sativa with a higher allocation of N in the shoots. However the origin of this N remains unclear.

Conclusion

After clipping, shoot regrowth is an important sink affecting the C distribution of newly assimilated C. To meet the demand of N for regrowth, the legume M. sativa increased the N allocation in the shoots. We assume that this is supported by a higher N uptake by the roots. The N pools in L. perenne were not affected by clipping. After shading, more C was allocated above-ground compared to normal light conditions leading to reduced translocation of assimilates in the roots of M. sativa. An increased need for N after shading was observed for the shoots of M. sativa, but the source of this N remains unclear. The results indicates that the allocation of recently assimilated C in plants and its translocation below-ground is strongly influenced by the altered substrate supply after clipping and shading. However, the reduced assimilation is of minor importance for the N distribution.

References

Augustine DJ, Dijkstra FA, Hamilton EW III, Morgan JA (2011) Rhizosphere interactions, carbon allocation, and nitrogen acquisition of two perennial North American grasses in response to defoliation and elevated atmospheric CO2. Oecologia 165:755–770

Avice JC, Ourry A, Lemaire G, Boucaud J (1996) Nitrogen and carbon flows estimated by 15N and 13C pulse-chase labeling during regrowth of alfalfa plant. Plant Physiol 112:281–290

Bakken AK, Macduff JH, Collison M (1998) Dynamics of nitrogen remobilization in defoliated Phleum pratense and Festuca pratensis under short and long photoperiods. Physiol Plant 103:426–436

Bardgett RD, Wardle DA, Yeates GW (1998) Linking above-ground and below-ground interactions: how plant responses to foliar herbivory influence soil organisms. Soil Biol Biochem 30:1867–1878

Blagodatskaya E, Blagodatsky S, Dorodnikov M, Kuzyakov Y (2010) Elevated atmospheric CO2 increases microbial growth rates in soil: results of three CO2 enrichment experiments. Glob Chang Biol 16:836–848

Cheng W, Coleman DC, Carroll CR, Hoffman CA (1993) In situ measurement of root respiration and soluble C concentrations in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem 25:1189–1196

Craine FM, Wedin DA, Chapin FS III (1999) Predominance of ecophysiological controls on soil CO2 flux in a Minnesota grassland. Plant Soil 207:77–86

de Neergaard A, Gorissen A (2004) Carbon allocation to roots, rhizodeposits and soil after pulse labelling: a comparison of white clover (Trifolium repens L.) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Biol Fertil Soils 39:228–234

Detling JK, Dyer MI, Winn DT (1979) Net photosynthesis, root respiration, and regrowth of Bouteloua gracilis following simulated grazing. Oecologia 41:127–134

Frank DA, Groffman PM (2009) Plant rhizospheric N processes: what we don't know and why we should care. Ecology 90:1512–1519

Gavrichkova O, Moscatelli MC, Kuzyakov Y, Grego S, Valentini R (2010) Influence of defoliation on CO2 efflux from soil and microbial activity in a Mediterranean grassland. Agr Ecosyst Environ 136:87–96

Gregory PJ, Atwell BJ (1991) The fate of carbon in pulse labelled crops of barley and wheat. Plant Soil 136:205–213

Guitian R, Bardgett RD (2000) Plant and soil microbial responses to defoliation in temperate semi-natural grassland. Plant Soil 220:271–277

Hamilton EW, Frank DA (2001) Can plants stimulate soil microbes and their own nutrient supply? Evidence from a grazing tolerant grass. Ecology 82:2397–2402

Hill P, Kuzyakov Y, Jones D, Farrar J (2007) Response of root respiration and root exudation to alterations in root C supply and demand in wheat. Plant Soil 291:131–141

Johansson G (1993) Carbon distribution in grass (Festuca pratensis L.) during regrowth after cutting-utilization of stored and newly assimilated carbon. Plant Soil 151:11–20

Jones DL, Hodge A, Kuzyakov K (2004) Plant and mycorrhizal regulation of rhizodeposition. New Phytol 163:459–480

KA5 (2005) Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung.Ad-Hoc-Arbeitsgruppe Boden:5. verbesserte und erweiterte Auflage, ISBN 978-3-510-95920-4, E. Schweizerbart Science Publishers

Kramer S, Marhan S, Ruess L, Armbruster W, Butenschoen O, Haslwimmer H, Kuzyakov Y, Pausch J, Schoene J, Scheunemann N, Schmalwasser A, Totsche KU, Walker F, Scheu S, Kandeler E (2012) Carbon flow into microbial and fungal biomass as a basis to understand the belowground food web in an agroecosystem. Pedobiologia, in press

Kuzyakov Y (2002) Review: factors affecting rhizosphere priming effects. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 16:382–396

Kuzyakov Y, Cheng W (2001) Photosynthesis controls of rhizosphere respiration and organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol Biochem 33:1915–1922

Kuzyakov Y, Cheng W (2004) Photosynthesis controls of CO2 efflux from maize rhizosphere. Plant Soil 263:85–99

Kuzyakov Y, Domanski G (2000) Carbon inputs into soil. Review. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 163:421–423

Kuzyakov Y, Gavrichkova O (2010) Time lag between photosynthesis and carbon dioxide efflux from soil: a review. Glob Chang Biol 16:3386–3406

Kuzyakov Y, Kretzschmar A, Stahr K (1999) Contribution of Lolium perenne rhizodeposition to carbon turnover of pasture soil. Plant Soil 213:127–136

Kuzyakov Y, Biryukova OV, Kuznetzova TV, Molter K, Kandeler E, Stahr K (2002) Carbon partitioning in plant and soil carbon dioxide fluxes and enzyme activities as affected by cutting ryegrass. Biol Fertil Soils 35:348–358

Lambers H, Posthumus L (1980) The effect of light intensity and relative humidity on growth rate and root respiration of Plantago lanceolata and Zea mays. J Exp Bot 31:1621–1630

Lötscher M, Klumpp K, Schnyder H (2004) Growth and maintenance respiration for individual plants in hierarchically structured canopies of Medicago sativa and Helianthus annuus: the contribution of current and old assimilates. New Phytol 164:305–316

Mackie-Dawson LA (1999) Nitrogen uptake and root morphological responses of defoliated Lolium perenne (L.) to a heterogeneous nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 209:111–118

Meharg AA, Killham K (1990) Carbon distribution within the plant and rhizosphere in laboratory and field grown Lolium perenne at different stages of development. Soil Biol Biochem 22:471–477

Merbach W, Mirus E, Knof G, Remus R, Ruppel S, Russow R, Gransee A, Schulze J (1999) Release of carbon and nitrogen compounds and their possible ecological importance. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 162:373–383

Merckx R, Dijkstra A, Hartog A, Veen JA (1987) Production of root-derived material and associated microbial growth in soil at different nutrient levels. Biol Fertil Soils 5:126–132

Morvan-Bertrand A, Pavis J, Boucaud J, Prud´homme MP (1999) Partitioning of reserve and newly assimilated carbon in roots and leaf tissues of Lolium perenne during regrowth after defoliation: assessment by 13C steady-state labelling and carbohydrate analysis. Plant Cell Environ 22: 1097–1108

Ourry A, Boucaud J, Salette L (1988) Nitrogen mobilization from stubble and roots during re-growth of defoliated perennial ryegrass. J Exp Bot 39:803–809

Paterson E, Sim A (1999) Rhizodeposition and C partitioning of Lolium perenne in axenic culture affected by nitrogen supply and defoliation. Plant Soil 216:155–164

Paterson E, Sim A (2000) Effect of nitrogen supply an defoliation on loss of organic compounds from roots of Festuca rubra. J Exp Bot 51:1449–1457

Phillips DA (1980) Efficiency of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legumes. Ann Rev Plant Physiol 31:29–49

Ryle GJA, Powell CE (1976) Effect of rate of photosynthesis on the pattern of assimilate distribution in the graminaceous plant. J Exp Bot 27:189–199

Shipley B (2002) Trade-offs between net assimilation rate and specific leaf area in determining relative growth rate: relationship with daily irradiance. Funct Ecol 16:682–689

Vance CP, Heichel GH (1991) Carbon in N2 fixation: limitation or exquisite adaption. Ann Rev Plant Physiol 42:373–392

Vance E, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1987) An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem 19:703–707

Volenec JJ, Ourry A, Joern BC (1996) A role for nitrogen reserves in forage regrowth and stress tolerance. Physiol Plant 97:185–193

Warembourg FR, Roumet C, Lafont F (2003) Differences in rhizosphere carbon-partitioning among plant species of different plant families. Plant Soil 256:347–357

Werth M, Kuzyakov Y (2008) Determining root-derived carbon in soil respiration and microbial biomass using 14C and 13C. Soil Biol Biochem 40:625–637

Zagal E (1994) Influence of light intensity on the distribution of carbon and consequent effects on mineralization of soil nitrogen in a barley (Hordeum vulgare L.)-soil system. Plant Soil 160:21–31

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Martina Gocke for her comments on the earlier version of the manuscript. Financial support for this work was provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Eric Paterson.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, A., Pausch, J. & Kuzyakov, Y. C and N allocation in soil under ryegrass and alfalfa estimated by 13C and 15N labelling. Plant Soil 368, 581–590 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1536-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1536-5