Abstract

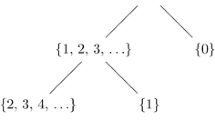

The standard definition of atomicity—the thesis that everything is ultimately composed of entities that lack proper parts—is satisfied by a model that is not atomistic. The standard definition is therefore an incorrect characterization of atomicity. I show that the model satisfies the axioms of all but the strongest mereology and therefore that the standard definition of atomicity is only adequate given some controversial metaphysical assumptions. I end by proposing a new definition of atomicity that does not require extensionality or unrestricted summation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All three agree on the first two definitions, though only Simons explicitly formulates the ‘mixed’ option. I mention these three works because they are generally regarded as the best introductions to mereology. It should be noted, though, that the standard definition of atomicity goes back at least to Goodman (1951) and appears in numerous other works on mereology.

I use Ax for ‘x is an atom’, Pxy for ‘x is a part of y’, PPxy for ‘x is a proper part of y’, Oxy for ‘x overlaps y’, and Uxy for ‘x underlaps y’. PPxy is taken to be primitive, Pxy is defined as \(PPxy\,\vee \, x=y,\,Ax\) is defined as \(\lnot \exists y PPyx,\,Oxy\) is defined as \( \exists z (Pzx\, \& \,Pzy),\) and Uxy is defined as \( \exists z (Pxz\, \& \,Pyz).\)

Where s(x) is the successor function and \(|X|\) is the cardinality of X.

A chain is any linearly ordered subset of a poset, and a chain is maximal if it is not a subset of any other chain in the poset.

Every non-terminating chain is infinite, but some infinite chains terminate (e.g., the set of all real numbers in [0, 1] ordered by \(\le \)). We will here only be concerned with infinite chains that fail to terminate. See Cotnoir and Bacon (2012) and Cotnoir (2013) for discussions of other kinds of infinite parthood chains.

I don’t use this alternative model in place of \({\mathfrak {M}}\) because doing so would overly complicate the exposition of the models considered later in the paper.

From here on I will only be concerned with atomicity, though what is said can be applied to developing mixed mereologies as well.

(10) and (7) together imply (8), hence (MM) becomes extensional with the addition of (10) and the closure versions of (AMM) and (AEM) are equivalent.

For the pairs of infinite sets, their product is the set further down the hierarchy; for the infinite/singleton pairs, their product is the singleton.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

In general, \({\sigma } x {\phi } x\) (the unique sum, x, of everything satisfying \({\phi }\)) is defined as \( {\upiota } z{\forall } w(Ozw\,\leftrightarrow \,\exists v({\phi } v\, \& \, Ovw))\), where \({\upiota }\) is the definite description operator.

References

Casati, R., & Varzi, A. (1999). Parts and places: The structures of spatial representation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cotnoir, A. J. (2013). Beyond atomism. Thought: A Journal of Philosophy, 2(1), 67–72.

Cotnoir, A. J., & Bacon, A. (2012). Non-wellfounded mereology. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(2), 187–204.

Goodman, N. (1951). The structure of appearance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Oliver, A., & Smiley, T. (2013). Plural logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simons, P. (1987). Parts: A study in ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Varzi, A. (2012). Mereology. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/mereology/.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Charles Cross, Yuri Balashov, Achille Varzi, Aaron Cotnoir, Jennifer Wang, and Matt Leonard for conversation and notes on earlier drafts. I am especially thankful to an anonymous reviewer whose comments were extremely helpful.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shiver, A. How do you say ‘everything is ultimately composed of atoms’?. Philos Stud 172, 607–614 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0321-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0321-0