Abstract

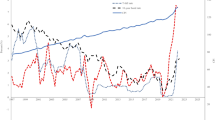

In this paper I analyze the London Monetary and Economic Conference of 1933, an almost forgotten episode in U.S. monetary history. I study how the Conference shaped dollar policy during the second half of 1933 and early 1934. I use daily data to investigate the way in which the Conference and related policies associated to the gold standard affected commodity prices, bond prices, and the stock market. My results show that the Conference itself did not impact commodity prices or the stock market. However, it had a small effect on bond prices. I do find that the events associated with the abandonment of the gold standard impacted prices in a significant way, even before the actual monetary and currency channels were at work. These results are consistent with the “change in regime” hypothesis of Sargent (1983).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On the economics views of the senior members of the “Brains Trust,” see Edwards (2017a).

See Pasvolsky (1933).

Roosevelt (1938), Vol. 2. P. 264–265.

Other scholars who have emphasized the role of the devaluation include Eichengreen and Sachs (1985), Eichengreen (1992), Bernanke (2000), Bernanke and James (1991), Temin (1991), Mundell (2000), and Irwin (2012). It is not possible to do justice to the copious literature on the Great Depression; see, however, Bordo et al. (2002), Bordo and Kydland (1995), Meltzer (2003), De Long (1990), Wigmore (1987), Obstfeld and Taylor (1997), and Calomiris and Wheelock (1998). Friedman and Schwartz (1963) continues to be the basic study on monetary policy during this period.

The Conference attracted considerable attention from contemporary analysts, including Lindley (1933) and Pasvolsky (1933). Schlesinger (1957) provides a detailed account, which draws on many of the participants recollections. Nussbaum (1957) dedicates two pages to it and Eichengreen (1992), in the most complete treatise on the gold standard, covers it in five pages. With time, however, the gathering has faded in stories on the evolution of economic policy during the first year of the Roosevelt Administration. Ahamed (2009) devotes two pages to it, as does Rauchway (2015). Eichengreen (2015) recently discusses the attempts to stabilize the exchanges in London in a comparative setting.

Since the publication of this important paper, a number of authors have investigated aspects of the change in regime explanation. See, for example, Eggertsson (2008), for an analysis using DSGE model, Coe (2002) for a probability switching model. See also Hausman (2013), Hausman et al. (2016), and Jalil and Rua (2016).

Hull knew, however, that these were empty words. At the last minute the President had informed him that he would not request from Congress authority to negotiate lower tariffs. The Times of London, “Sweeping U.S. measures,” June 5, 1933, p. 15.

League of Nations (1933), No. 5, p. 26.

League of Nations (1933), No. 4, p. 12.

The New York Times, “Paris doubts help at London parley,” June 12, 1933, p. 2.

The New York Times, “Paris doubts help at London parley,” June 12, 1933, p. 2.

The New York Times, “France insistent on stable money,” June 12, 1933, p. 25.

Lindley (1933), p. 198.

Roosevelt (1938), Vol 2. P. 166–167.

Morgenthau Diaries, Volume 1, May 29, 1933. P. 37.

Feis (1966), p. 144.

Leith-Ross (1968), p. 168.

For a discussion on exchange rate misalignment see Edwards (2011) and the literature cited therein.

White (1935).

The rumor was started after James Cox, the former Governor of Ohio, and newly appointed chair of the Monetary Committee of the Conference, uttered that a $4.00 per pound rate was appropriate.

Roosevelt (1938), Vol. 2. P. 245.

Times of London, “America’s Two Paths.” June 21, 1933; pg. 14.

In 1932 a group of economists criticized the Fed for not undertaking counter cyclical policy. See Appendix I in Wright (1932). In mid-1933 a smaller group of Chicago economists made a more specific proposal for reforming the monetary system, which they sent to the Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace. This scheme received the name of the “Chicago Plan.” See Tavlas (1997) for a detailed analysis.

Lindley (1933), p. 204–206.

Lindley (1933), p. 206.

Moley (1939), p 235.

Warburg (1934), p. 117.

All the quotes in this paragraph come from Roosevelt (1938), Vol. 2. P. 264–265.

Hull (1948), Vol. 1, p. 262, emphasis added.

Hull (1948), Vol. 1, p. 263.

Roosevelt (1938), Vol. 2, p. 186, emphasis added.

The New York Times (NYT), December 31, 1933, p. 2 XX. For a formal statistical analysis of dollar gyrations during that period see Edwards (2017b).

The Thomas Amendment gave the President several options for generating inflation. The devaluation of the dollar was one of them. For details see, for example, Moley (1939).

Roosevelt (1938), p. 137. Emphasis added.

For details see Edwards (2017b).

This bond was issued on May 8, 1918, and was redeemable between 1933 and 1938.

For details on the abrogation see Edwards et al. (2015).

See Lippman (1936) for a collection of columns written during 1933 on agricultural prices and exchange rates.

During 1933 the discount rate was increased once and reduced thrice. See Federal Reserve Board of Governors (1943). See, also, the discussion below.

The U.S. issued bonds without the gold clause for the first time in 16 years in mid-June 1933. Thus, it is not possible to compare yields on gold and non-gold bonds before that time. For a thorough discussion, see Edwards et al. (2015). The Supreme Court ruled on the abrogation on February 18, 1935.

See Samuelson and Kross (1969), Volume 4, p. 377.

This statement assumes that we are sitting in late June 1933; we cannot see the data that became available after that time.

References

Ahamed L (2009) Lords of finance: the bankers who broke the world. Random House

Bernanke B (2000) Essays on the great depression. Princeton University Press

Bernanke B, James H. (1991). The gold standard, deflation, and financial crisis in the Great Depression: An international comparison. In Financial markets and financial crises (pp. 33–68). University of Chicago Press

Bordo MD, Kydland FE (1995) The gold standard as a rule: an essay in exploration. Explor Econ Hist 32(4):423–464

Bordo MD, Choudhri EU, Schwartz AJ (2002) Was expansionary monetary policy feasible during the great contraction? an examination of the gold standard constraint. Explor Econ Hist 39(1):1–28

Calomiris C, Wheelock D. (1998). Was the Great Depression a watershed for American monetary policy?. In The defining moment: The great depression and the American economy in the twentieth century (pp. 23–66). University of Chicago Press

Cassel G (1923) Money and foreign exchange after 1914. Constable

Coe PJ (2002) Financial crisis and the great depression: a regime-switching approach. J Money, Credit, Bank 34(1):76–93

De Long JB. (1990). Liquidation cycles: old-fashioned real business cycle theory and the great depression (No. w3546). National Bureau of Economic Research

Edwards S (2011) Exchange-rate policies in emerging countries: eleven empirical regularities from Latin America and East Asia. Open Econ Rev 22(4):533

Edwards S. (2017a), Gold, the brains trust and Roosevelt, History of Political Economy, Winter

Edwards S. (2017b), Keynes and the dollar in 1933, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper

Edwards S, Longstaff FA, Marin AG. (2015). The US Debt Restructuring of 1933: Consequences and Lessons (no. w21694). National Bureau of Economic Research

Eggertsson GB (2008) Great expectations and the end of the depression. Am Econ Rev 98(4):1476–1516

Eichengreen B. (1992). Golden fetters: the gold standard and the great depression, 1919–1939. Oxford University Press

Eichengreen B. (2015). Before the plaza: the exchange rate stabilization attempts of 1925, 1933, 1936 and 1971

Eichengreen B, Sachs J (1985) Exchange rates and economic recovery in the 1930s. J Econ Hist 45(04):925–946

Eichengreen B, Uzan M. (1990). The 1933 world economic conference as an instance of failed international cooperation. Department of Economics, UCB

Federal Reserve Board (1943) Banking and monetary statistics. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington DC

Feis H. (1966). Characters in Crisis. Boston, Toronto: Little1, Brown, and Company

Fisher I (1913) A compensated dollar. Q J Econ 27:385–397

Fisher I. (1920). Stabilizing the dollar: a plan to stabilize the general price level without fixing individual prices. Macmillan

Friedman M, Schwartz AJ. (1963). A monetary history of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton University Press

Harris SE (1936) Exchange Depreciation: Its Theory and Its History, 1931–35, with Some Consideration of Related Domestic Policies 53. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hausman JK. (2013). New deal policies and recovery from the great depression

Hausman J, Rhode P, Wieland J (2016). Recovery from the Great Depression: The farm channel in Spring 1933, University of Michigan

Hull C, (1948). The Memoirs of Cordell Hull (two volumes). Macmillan

Irwin DA (2012) Gold sterilization and the recession of 1937–1938. Financial Hist Rev 19(03):249–267

Jalil A, Rua G (2016) Inflation expectations and recovery from the depression in 1933: evidence from the narrative record. Explor Econ Hist 62:26–50

Keynes JM. (1924). A tract on monetary reform. McMillan

Keynes JM. (1933). The means to prosperity. McMillan

League of Nations (1933), Journal of the monetary and economic conference, Various issues London, 1933

Leith-Ross F. (1968). Money talks: fifty years of international finance: the autobiography of Sir Frederick Leith-Ross. Hutchinson

Lindley EK. (1933). Roosevelt’s revolution, first phase. Viking

Lippman W (1936) Interpretations. MacMillan

Meltzer AH. (2003). A History of the Federal Reserve, Vol. 1 Chicago

Moley R. (1939). After seven years. Harper & Bros

Moley R (1966) The first new deal. Harcourt

Morgenthau Jr., H. (1933). Farm credit diary. The Morgenthau Papers at the Roosevelt Presidential Library

Mundell RA (2000) A reconsideration of the twentieth century. Am Econ Rev:327–340

Nussbaum A (1957) A history of the dollar. Columbia University Press, New York

Obstfeld M, Taylor AM. (1997). The great depression as a watershed: international capital mobility over the long run (No. w5960). National Bureau of Economic Research

Pasvolsky L. (1933). Current monetary issues. Brookings Institution

Rauchway E (2015) The money makers. Basic Books

Romer CD (1992) What ended the great depression? J Econ Hist 52(04):757–784

Roosevelt FD. (1938) The public papers and addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Vols. 1 and 2. Random House

Samuelson P, Kross HE. (Ed.). (1969). Documentary history of banking and currency in the United States (Vol. 4). Chelsea House Publishers

Sargent TJ. (1983). Stopping moderate inflations: the methods of Poincare and Thatcher. Inflation, debt and indexation, MIT Press, Cambridge, 54–96.

Schlesinger AM (1957) The age of Roosevelt (Vol. 1). 3 vols. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Sumner S (2001) Roosevelt, Warren, and the gold-buying program of 1933. Res Econ Hist 20:135–172

Sumner S. (2015). The midas paradox. Independent institute

Tavlas GS (1997) Chicago, Harvard, and the doctrinal foundations of monetary economics. J Polit Econ:153–177

Temin P. (1991). Lessons from the great depression. MIT Press Books, 1

Temin P, Wigmore BA (1990) The end of one big deflation. Explor Econ Hist 27(4):483–502

Times of London, (1933) The Several Issues

Warburg JP (1934) The money muddle. Knopf

Warren GF, Pearson FA (1931) Prices. Wiley

Warren GF, Pearson FA (1935) Gold and prices. Wiley

White HD. (1935), Recovery Program: The International Monetary Aspect, The Harry Dexter White Papers (MC 104), Box 13, Folder 13. Princeton University Library Archives

Wigmore BA (1987) Was the Bank holiday of 1933 caused by a run on the dollar? J Econ Hist 47(03):739–755

Wright Q (1932) Gold and monetary stabilization. University of Chicago Press

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I thank Michael Poyker for his assistance. I thank Michael Bordo and George Tavlas for comments. I have benefitted from conversations with Ed Leamer.

Appendix: Data Sources

Appendix: Data Sources

1.1 Commodity Prices

(Source: Daily; New York Times).

Closing wholesale cash $ prices for commodities in the New York Market.

Wheat #2 red, per bushel.

Corn #2 yellow, per bushel.

Rye #2 Western, per bushel.

Cotton, middling upland, per pounds

1.2 Bond Prices

(Source: Daily; New York Times).

Fourth Liberty Loan: Liberty bond 4th 41/4s, 1933–38, issued May 8, 1918, interest paid on April 15, October 15; Closing cash $ prices for bonds traded in on the Stock Exchange.

1.3 Exchange Rates

(Source: GFDatabase).

https://www.globalfinancialdata.com/Databases/GFDatabase.html

1.4 Events related to Gold and London Conference

The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Chicago Tribune, Times of London.

1.5 Gold Prices

Taken from Warren and Pearson (1935), P. 168–169.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, S. The London Monetary and Economic Conference of 1933 and the End of the Great Depression. Open Econ Rev 28, 431–459 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9435-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9435-2