Abstract

We use the Johansen cointegration approach to assess the empirical validity of the purchasing power parity (PPP) between the UK and Germany since the introduction of the euro. We conduct the empirical analysis in the context of the global financial crisis that began in 2007 and find that it directly affects the cointegration space. We fail to validate the Johansen and Juselius (1992) original hypothesis that nonstationarity of PPP associates with the nonstationarity of interest rate differentials to produce a stationary relation. On the other hand, we do not reject PPP. We find that PPP cointegrates with inflation differentials. We also find, contrary to conventional wisdom, that (i) equilibrium adjustment occurs between the German and UK inflation rates, while weak exogeneity exists for the German and UK interest rates and the PPP condition, and (ii) three common trends associated with the German interest rate the UK interest rate, and the PPP condition “push” the system with the German interest rate and the PPP condition playing dominant roles in affecting inflation in both Germany and the UK. These results cast serious doubt on the presumed independence of the UK monetary policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Germany and the UK form a most important trade relationship. In 2011, only the US surpassed Germany in UK exports and Germany did hold the position as the top trading partner for imports, accounting for 11.06 % and 12.87 % of the UK’s primary exports and imports, respectively. In comparison, the US accounted for 14.71 % and 9.74 %, respectively.

Mazumder and Pahl (2013) construct counterfactual exercises designed to compute the unemployment and output in the UK, if they had joined the euro in 1999. Their overall results indicate that the UK made the correct decision not to join the euro back in 1999. The recent sovereign debt crisis that substantially affected some of the countries of the Euro area, most notably Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain, makes it even more unlikely that the UK will join the common European currency in the near future. Germany and the UK appear to have withstood the disruptive macroeconomic shocks of the crisis. Arghyroua and Kontonikas (2012) provide a detailed empirical investigation of the crisis.

Few empirical studies (Alquist and Chinn 2002; Gadea et al. 2004; Lopez and Papell 2007; Hall et al. 2013) examine PPP within the Euro area. Alquist and Chinn (2002) find a nonstationary real exchange rate, suggesting that PPP does not hold in the Euro area. Gadea et al. (2004) find some support for PPP within the Euro area after incorporating two structural breaks. Also, scant evidence exists of PPP validity between the Euro area and other major economies. Lopez and Papell (2007) study the convergence to PPP in the Euro area from 1973 to 2001 and find that PPP holds better within the Euro area than between the Euro area and other European countries. Alquist and Chinn (2002), using data on the “synthetic” euro-dollar exchange rate for 1985 to 2001, rejects PPP, but documents a stable long-run relationship between the real euro-dollar rate, productivity differentials, and the real price of oil. Koedijk et al. (2004), in addition to examining the validity of PPP within the Euro area, also use “synthetic” euro data to study PPP validity between the Euro area and other major economies. They find that with the exception of Switzerland, PPP does not hold. Manzur and Chan (2010), using data through April 2007, construct a measure of “pooled” inflation among the 12 Euro countries and use this measure to test, in a simple regression framework, relative PPP for the euro against the currencies of Japan, the UK, and the US. Their results provide weak support for relative PPP in the case of dollar-euro and pound-euro exchange rates, and rejects relative PPP for the yen-euro. Hall et al. (2013) apply a time-varying-coefficient technique to investigate the homogeneity condition underlying the PPP for nine euro area countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain) as well as for the euro area as a whole, using data from January 1999 to March 2011. Using the US as the foreign country, Hall et al. (2013) find strong support for long-run homogeneity, thus providing strong support for PPP.

International finance theory typically argues that financial flows and interest rate parity dominate exchange rate determination in the short run while goods and service flows and purchasing power parity dominate in the long run. This suggests that we will more likely uncover evidence supporting UIP rather than PPP. But, UIP suffers from the evidence on the success of carry trade, whereby investors sell currencies in markets with low interest rates to buy currencies in markets with high interest rates, which runs counter to UIP. See Hansen and Hodrick (1983).

We use not seasonally adjusted harmonized indices of consumer prices (HCPI), 2005 = 100. We compute the rates of inflation as the logarithmic first difference of consumer prices. Data on exchange rate and price indices come from the statistical database of the European Central Bank (sdw.ecb.europa.eu), while data on bond yields come from the OECD Main Economic Indicators database (stats.oecd.org). We convert annual interest rates to monthly rates and divide by 100 to make the estimates comparable with logarithmic monthly inflation rates.

A longer version posted at http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html provides extensive discussion of tests reported in Section 3 as well as additional tests..

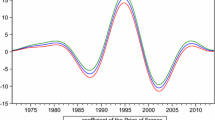

The multivariate versions of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the Hannan-Quinn (H-Q) criterion suggest a lag length of 2, given a maximum lag order of 4. We cannot justify the VAR(2) specification, however, as diagnostic tests suggest residual serial correlation. Consequently, we specify a VAR(3) model, using a number of specification tests. This implies 2 lags of the first differences of the variables in the VEC model of the data. Following Johansen (1995), we specify the model to include a restricted constant, since the variables do not show growth. Thus, the constant term should appear in the cointegrating space, implying that some equilibrium means in the cointegration space can differ from zero. We do not include a linear deterministic trend, since a trend is inconsistent with PPP (Papell and Theodoridis 1998; Amara and Papell 2006). Excluding a linear deterministic trend also proves consistent with the unit-root analysis. We include three different types of dummy variables. First, following Johansen (1995), we introduce centered seasonal dummy variables to account for seasonality in the data. Second, we use a shift dummy variable to account for the developments of the global economic crisis. We assume that the break occurs in 2007:10 based on the visual inspection and institutional consideration about the beginning of the global financial crisis and sub-prime lending crisis in the housing markets. The dummy variable equals 0 before October 2007 and 1 from October 2007 onward. Finally, we include an intervention dummy variable in December 2008 to account for a residual exceeding in absolute value 3σ ε .

A longer version of this paper reports the test statistics referred to in this and the next three paragraphs. See http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html.

Graphs appear in longer version posted at http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html.

The unknown sampling distribution of the eigenvalues, which precludes testing whether eigenvalues significantly differ from one, makes this a tentative conclusion.

We note that rejecting the hypothesis that r = 1 runs counter to the frequent use of single equation models in the exchange rate determination literature. That is, a single equation model implies just one long-run cointegrating relationship between the relevant variables, whereas concluding that r = 2 means that existing data require a more complex model.

If we impose r = 3 when the appropriate rank is r = 2, then the third root comes closer to unity, and we should reduce r from 3 to 2. When r = 2, we observe the lowest first root beyond the unit root is 0.562. See Juselius (2006).

By fixing the estimates of the short-run parameters, we reduce the variance of the long-run parameters, which is the primary interest of cointegration analysis (Hansen and Johansen 1999). This motivates the R1(t)-form.

We fix the base period, January 1999 to December 2002, at about 35 percent of the sample, following the suggestion of Brüggemann et al. (2003).

Graphs of the discussions in this and the next paragraph appear in the longer version of the paper posted at http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html

See http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html for graphs of these tests.

During the transition period, which lasts from January 1999 to December 2001, transactions in the countries of the Euro area could use both the euro and national currencies. During this transition period, the euro only serves an accounting unit, and euro notes and coins only start circulating in January 2002, when countries withdraw their national currencies from circulation.

See http://ideas.repec.org/p/uct/uconnp/2012-46.html for graphs of the tests in this paragraph.

Whereas likelihood ratio testing for cointegrating rank leads to a nonstandard inference situation, conditional likelihood ratio testing, for a given cointegrating rank, produces standard asymptotically chi-squared test statistics.

We can justify this result, however, by appealing to the “imperfect knowledge economics” approach developed by Frydman and Goldberg (2003, 2006). Under imperfect information expectations, exchange rates fluctuations do not represent movements toward a fundamental purchasing power equilibrium, but movements generated by traders’ behavior in the foreign exchange market (Juselius and MacDonald 2004).

The hypotheses conform to β = (Hφ,ψ), where H is the design matrix, φ contains the restricted parameters, and ψ is a vector of freely estimated parameters. For details, see Juselius (2006).

Since the rank equals two (r = 2), we can only test for cointegration, where theoretical relations restrict at least two of the parameters. The degrees of freedom of the χ 2(υ) distribution, where υ = k – (r – 1) and k is the number of restrictions (Juselius 2006), impose this requirement.

This result questions the stationarity of the inflation rate differential (H 2). That is, if the inflation rate differential is really I(0), then it cannot cointegrate with ppp t , which is I(1).

For completeness, we also test, following Pedersen (2002b), for cointegration between ppp t and the rate of inflation of Germany or the UK separately, which implies that the adjustment costs fall unilaterally on only one country. In each case, we reject the hypotheses that ppp t forms a stationary relation with either the German inflation (χ 2(2) =11.739 p ‐ value = 0.003) or the UK inflation (χ 2(2) = 5.264 p ‐ value = 0.072) rate alone at the 5-percent level.

The unrestricted estimates of the α matrix, obtained without imposing the weak exogeneity restriction, do not significantly differ from zero.

Ball (2012) observes that a central question for monetary policy is how to respond to shocks that affect exchange rates. Our findings indicate that monetary policies that stabilize output will not keep inflation under control.

This argument is also made by Manzur and Chan (2010).

References

Adler M, Lehmann B (1983) Deviations from purchasing power parity in the long run. J Financ 38:1471–1487

Alquist R and Chinn M (2002) The Euro and the productivity puzzle: an alternative interpretation. NBER Working Paper No. 8824

Amara J, Papell DH (2006) Testing for purchasing power parity using stationary covariates. Appl Financ Econ 16:29–39

Arghyroua MG, Kontonikas A (2012) The EMU sovereign-debt crisis: fundamentals, expectations and contagion. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 22:658–667

Ball L (2012) Policy responses to exchange-rate movements. Open Econ Rev 21:187–199

Bank of England (2013) web site on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Framework http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/Pages/framework/framework.aspx

Barrios S, Brülhart M, Elliott RJ, Sensier M (2003) A tale of two cycles: co-fluctuations between UK regions and the Euro zone. Manch Sch 71:265–292

Baum CF, Barkoulas JT, Caglayan M (2001) Nonlinear adjustment to purchasing power parity in the post-Bretton Woods era. J Int Money Financ 20:379–399

Banerjee A, Cockerell L, Russel B (2001) An I(2) analysis of inflation and the markup. J Appl Econ 16:221–240

Brüggemann A, Donati P, and Warne A (2003) Is the demand for Euro area M3 stable? European Central Bank Working Paper No. 255

Camacho M, Perez-Quiros G, Saiz L (2008) Do European business cycles look like one? J Econ Dyn Control 32:2165–2190

Camarero M, Tamarit C (1996) Cointegration and the PPP and the UIP hypotheses: an application to the Spanish integration in the EC. Open Econ Rev 7:61–76

Caporale GM, Kalyvitis S, Pittis N (2001) Testing for PPP and UIP in an FIML framework: some evidence for Germany and Japan. J Policy Model 23:637–650

Chen S, Wu J (2000) A re-examination of purchasing power parity in Japan and Taiwan. J Macroecon 22:271–284

Cheung Y-W, Lai KS (1993) Long–run purchasing power parity during the recent float. J Int Econ 34:181–192

Chortareas G, Kapetanios G (2009) Getting PPP right: identifying mean-reverting real exchange rates in panels. J Bank Financ 33:390–404

Corbae PD, Ouliaris S (1988) Cointegration and tests of purchasing power parity. Rev Econ Stat 70:508–511

Coakley J, Fuertes AM (1997) New panel unit root tests of PPP. Econ Lett 57:17–22

Dickey DA, Fuller WA (1979) Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Stat Assoc 74:427–431

Dornbusch R (1976) Expectations and exchange rate dynamics. J Polit Econ 84:1161–1176

Doornik JA, Hansen H (2008) An omnibus test for univariate and multivariate normality. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 70:927–939

Duchesne P, Lalancette S (2003) On testing for multivariate arch effects in vector time series models. Can J Stat 31:275–292

Edison HJ (1987) Purchasing power parity in the long run: a test of the dollar/pound exchange rate (1890–1978). J Money Credit Bank 19:376–387

Elliott G, Rothenberg TJ, Stock JH (1996) Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica 64:813–836

Enders W, Falk B (1998) Threshold autoregressive, median unbiased, and cointegration tests of purchasing power parity. Int J Forecast 14:171–186

Engle R (1988) Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica 96:893–920

European Central Bank (2013) website on the European Central Bank Monetary Policy. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/intro/html/index.en.html

Feenstra R, Taylor A (2012) International macroeconomics, 2nd edn. Worth Publishers, New York

Frankel J, Rose A (1996) A panel project on purchasing power parity: mean reversion within and between countries. J Int Econ 40:209–224

Frenkel J (1976) A monetary approach to the exchange rate: doctrinal aspects and empirical evidence. Scand J Econ 76:200–224

Frydman R, Goldberg M (2003) Imperfect knowledge expectations, uncertainty adjusted UIP and exchange rate dynamics. In: Aghion P, Frydman R, Stiglitz J, Woodford M (eds) Knowledge, information and expectations in modern macroeconomics: in honor of Edmund S. Phelps. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Frydman R, Goldberg M (2006) Exchange rates and risk in a world of imperfect knowledge: a new approach to modeling asset markets. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gadea M, Montañés A, Reyes M (2004) The European Union and the US dollar: From post-Bretton-Woods to the Euro. J Int Money Financ 23:1109–1136

Glen J (1992) Real exchange rates in the short, medium, and long run. J Int Econ 33:147–166

Gregory AW (1994) Testing for cointegration in linear quadratic models. J Bus Econ Stat 12:347–360

Gregory AW, Pagan AR, Smith GW (1993) Estimating linear quadratic models with integrated processes. In: Phillips PCB (ed) Models, methods, and applications of econometrics: essays in honor of A.R. Bergstrom, Ch. 15. Basil Blackwell, Cambridge

Grilli V, Kaminsky G (1991) Nominal exchange rate regimes and the real exchange rate: evidence from the United States and Great Britain, 1985–1986. J Monet Econ 27:191–212

Hacker RS, Abdulnasser H-J (2005) A test for multivariate ARCH effects. Appl Econ Lett 12:411–417

Hakkio CS, Rush M (1991) Cointegration: how short is the long run? J Int Money Financ 10:571–581

Hall SG, Hondroyiannis G, Kenjegaliev A, Swamy PAVB, Tavlas GS (2013) Is the relationship between prices and exchange rates homogeneous? J Int Money Financ 37:411–438

Hansen LP, Hodrick RJ (1983) Risk averse speculation in the forward exchange market: an econometric analysis of linear models. In: Frenkel JA (ed) Exchange Rates and International Macroeconomics. University of Chicago Press, pp 113–142

Hansen H, Johansen S (1999) Some tests for parameter constancy in cointegrated VAR-models. Econ J 2:306–333

Harris D, Leybourne S, McCabe B (2005) Panel stationarity tests for purchasing power parity with cross-sectional dependence. J Bus Econ Stat 23:395–409

Hatzinikolaou D, Polasrk M (2005) The commodity-currency view of the Australian dollar: a multivariate cointegration approach. J Appl Econ 8:81–99

Holmes MJ, Maghrebi N (2004) Asian real interest rates, non-linear dynamics and international parity. Int Rev Econ Financ 13:387–405

Hosking JRM (1980) The multivariate portmanteau statistic. J Am Stat Assoc 75:602–607

Huizinga J (1987) An empirical investigation of the long-run behavior of real exchange rates, In Brunner K and Meltzer A eds., Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 27, 149–214

Hunter J (1992) Tests of cointegrating exogeneity for PPP and uncovered interest rate parity for the UK. J Policy Model Spec Issue Cointegration Exog Policy Anal 14:453–463

Johansen S (1988) Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J Econ Dyn Control 12:231–254

Johansen S (1991) Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica 59:1551–1580

Johansen S (1995) Likelihood-based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Oxford University Press, New York

Johansen S, Juselius K (1990) Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration – with applications to the demand for money. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 52:169–210

Johansen S, Juselius K (1992) Testing structural hypotheses in a multivariate cointegration analysis of the PPP and UIP for UK. J Econ 53:211–244

Juselius K (1995) Do purchasing power parity and uncovered interest parity hold in the long run? An example of likelihood inference in a multivariate time-series model. J Econ 69:211–240

Juselius K (2006) The cointegrated VAR model – methodology and applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Juselius K and MacDonald R (2000) International parity relationships between Germany and the United States: A joint modelling approach. University of Copenhagen, Institute of Economics Discussion Paper 00/10

Juselius K, MacDonald R (2004) International parity relationships between the US and Japan. Jpn World Econ 16:17–34

Kilian L, Taylor MP (2003) Why is it so difficult to beat the random walk forecast of exchange rates? J Int Econ 60:85–107

Kim Y (1990) Purchasing power parity in the long run: a cointegration approach. J Money Credit Bank 22:491–503

Koedijk KJ, Tims B, van Dijk MA (2004) Purchasing power parity and the euro area. J Int Money Financ 23:1081–1107

Kontolemis ZG and Samiei H (2000) The UK business cycle, monetary policy, and EMU entry. IMF Working Paper WP/00/210

Kuo BS, Mikkola A (1999) Re-examining long-run purchasing power parity. J Int Money Financ 18:251–266

Layton AP, Stark JP (1990) Co-integration as an empirical test of purchasing power parity. J Macroecon 12:125–136

Ljung GM, Box GEP (1978) On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 65:297–303

Lopez C, Papell DH (2007) Convergence to purchasing power parity at the commencement of the Euro. Rev Int Econ 15:1–16

Lothian JR (1997) Multi-country evidence on the behavior of purchasing power parity. J Int Money Financ 16:19–35

Lothian JR, Taylor M (1996) Real exchange rate behavior: the recent float from the perspective of the past two centuries. J Polit Econ 104:488–510

MacDonald R (1996) Panel unit root tests and real exchange rates. Econ Lett 50:7–11

Mazumder S, Pahl R (2013) What if the UK had joined the euro in 1999? Open Econ Rev 24:447–470

Manzur M, Chan F (2010) Exchange rate volatility and purchasing power parity: does euro make any difference? Int J Bank Financ 7:99–118

Mark NC (1990) Real and nominal exchange rates in the long run: an empirical investigation. J Int Econ 28:115–136

Merton RC (1973) An intertemporal capital asset pricing model. Econometrica 41:867–887

Miyakoshi T (2004) A testing of the purchasing power parity using a vector autoregressive model. Empir Econ 29:541–552

Mussa M (1976) The exchange rate, the balance of payments, and monetary and fiscal policy under a regime of controlled floating. Scand J Econ 78:229–248

O’Connell P (1998) The overvaluation of purchasing power parity. J Int Econ 44:1–19

Obstfeld M, Rogoff K (1995) Exchange rate dynamics redux. J Polit Econ 103:624–660

Ozmen E, Gokcan A (2004) Deviations from PPP and UIP in a financially open economy: the Turkish evidence. Appl Financ Econ 14:779–784

Papell D (1997) Searching for stationarity: purchasing power parity under the current float. J Int Econ 43:313–332

Papell DH, Theodoridis H (1998) Increasing evidence of purchasing power parity over the current float. J Int Money Financ 17:41–50

Pedersen M (2002a) Does the PPP hold within the US? European University Institute Working Paper ECO No. 2002/18. http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/790/ECO2002-18.pdf?sequence=1

Pedersen M (2002b) Testing the PPP in a cointegrated VAR when inflation rates are non-stationary. With an application to the UK and Germany. Mimeo. Available from the author

Pedroni P (1995) Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Indiana University Working Papers in, Economics 95–013

Pedroni P (2001) Purchasing power parity in cointegrated panels. Rev Econ Stat 83:727–731

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith R (2000) Structural analysis of vector error correction models with exogenous I(1) variables. J Econ 97:293–343

Rapach DE (2003) International evidence on the long run impact of inflation. J Money Credit Bank 35:23–48

Rogoff K (1996) The purchasing power parity puzzle. J Econ Lit 34:647–668

Sarno L, Taylor MP (2002) The economics of exchange rate. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sjoo B (1995) Foreign transmission effects in Sweden: do PPP and UIP hold in the long run? Adv Int Bank Financ 1:129–149

Snaith S (2012) The PPP debate: multiple breaks and cross-sectional dependence. Econ Lett 115:342–344

Solnik RE (1974) An equilibrium model of the international capital market. J Econ Theory 8:500–524

Taylor M (1988) An empirical examination of long-run purchasing power parity using cointegration techniques. Appl Econ 20:1369–1381

Taylor MP, Sarno L (1998) The behaviour of real exchange rates during the post-Bretton Woods period. J Int Econ 46:281–312

Taylor AM, Taylor MP (2004) The purchasing power parity debate. J Econ Perspect 18:135–158

Wu J, Chen S (1999) Are real exchange rates stationary based on panel unit-root tests? Evidence from Pacific basin countries. Int J Financ Econ 4:243–252

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of a referee and the editor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Canarella, G., Miller, S.M. & Pollard, S.K. Purchasing Power Parity Between the UK and Germany: The Euro Era. Open Econ Rev 25, 677–699 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9309-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9309-9