Abstract

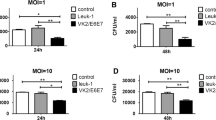

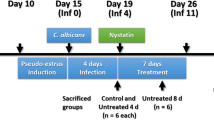

Mouse model is an appropriate tool for pathogenic determination and study of host defenses during the fungal infection. Here, we established a mouse model of candidiasis with concurrent oral and vaginal mucosal infection. Two C. albicans strains sourced from clinical candidemia (SC5314) and mucosal infection (ATCC62342) were tested in ICR mice. The different combinational panels covering estrogen and immunosuppressive agents, cortisone, prednisolone and cyclophosphamide were used for concurrent oral and vaginal candidiasis establishment. Prednisolone in combination with estrogen proved an optimal mode for concurrent mucosal infection establishment. The model maintained for 1 week with fungal burden reached at least 105 cfu/g of tissue. This mouse model was evaluated by in vivo pharmacodynamics of fluconazole and host mucosal immunity of IL-17 and IL-23. Mice infected by SC5314 were cured by fluconazole. An increase in IL-23 in both oral and vaginal homogenates was observed after infection, while IL-17 only had a prominent elevation in oral tissue. This model could properly mimic complicated clinical conditions and provides a valuable means for antifungal assay in vivo and may also provide a useful method for the evaluation of host–fungal interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Xu J, Boyd CM, Livingston E, Meyer W, Madden JF, Mitchell TG. Species and genotypic diversities and similarities of pathogenic yeasts colonizing women. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3835–43.

Angebault C, Djossou F, Abelanet S, Permal E, Ben SM, Diancourt L, et al. Candida albicans is not always the preferential yeast colonizing humans: a study in Wayampi Amerindians. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1705–16.

Ashman RB. Protective and pathologic immune responses against Candida albicans infection. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3334–51.

Fidel PL Jr. Host defense against oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis: site-specific differences. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1999;16:8–15.

Fidel PL Jr. Distinct protective host defenses against oral and vaginal candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2002;40:359–75.

Merenstein D, Hu H, Wang C, Hamilton P, Blackmon M, Chen H, et al. Colonization by Candida species of the oral and vaginal mucosa in HIV-infected and noninfected women. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29:30–4.

de Repentigny L. Animal models in the analysis of Candida host-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:324–9.

Naglik JR, Fidel PL Jr, Odds FC. Animal models of mucosal Candida infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;283:129–39.

Junqueira JC. Models hosts for the study of oral candidiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;710:95–105.

Szabo EK, MacCallum DM. The contribution of mouse models to our understanding of systemic candidiasis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;320:1–8.

MacCallum DM, Odds FC. Temporal events in the intravenous challenge model for experimental Candida albicans infections in female mice. Mycoses. 2005;48:151–61.

Kamai Y, Kubota M, Kamai Y, Hosokawa T, Fukuoka T, Filler SG. New model of oropharyngeal candidiasis in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3195–7.

Okada M, Hisajima T, Ishibashi H, Miyasaka T, Abe S, Satoh T. Pathological analysis of the Candida albicans-infected tongue tissues of a murine oral candidiasis model in the early infection stage. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:444–50.

Mosci P, Pericolini E, Gabrielli E, Kenno S, Perito S, Bistoni F, et al. A novel bioluminescence mouse model for monitoring oropharyngeal candidiasis in mice. Virulence. 2013;4:250–4.

Samaranayake YH, Samaranayake LP. Experimental oral candidiasis in animal models. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:398–429.

Costa AC, Pereira CA, Junqueira JC, Jorge AO. Recent mouse and rat methods for the study of experimental oral candidiasis. Virulence. 2013;4:391–9.

Deslauriers N, Cote L, Montplaisir S, de Repentigny L. Oral carriage of Candida albicans in murine AIDS. Infect Immun. 1997;65:661–7.

Fidel PL Jr, Cutright J, Steele C. Effects of reproductive hormones on experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:651–7.

Rahman D, Mistry M, Thavaraj S, Challacombe SJ, Naglik JR. Murine model of concurrent oral and vaginal Candida albicans colonization to study epithelial host-pathogen interactions. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:615–22.

Zhao JJ, Shen YN, Chen W, Liu WD. A murine model of Candida albicans vaginitis. Chin J Dermatol. 2002;35:346–8.

Takakura N, Sato Y, Ishibashi H, Oshima H, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H, et al. A novel murine model of oral candidiasis with local symptoms characteristic of oral thrush. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:321–6.

Solis NV, Filler SG. Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:637–42.

Taylor BN, Fichtenbaum C, Saavedra M, Slavinsky IJ, Swoboda R, Wozniak K, et al. In vivo virulence of Candida albicans isolates causing mucosal infections in people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:955–9.

Chamilos G, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Role of mini-host models in the study of medically important fungi. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:42–55.

Zhang JE, Luo D, Chen RY, Yang YP, Zhou Y, Fan YM. Feasibility of histological scoring and colony count for evaluating infective severity in mouse vaginal candidiasis. Exp Anim. 2013;62:205–10.

Yang J, Lu Q, Liu W, Wan Z, Wang X, Li R. Cyclophosphamide reduces dectin-1 expression in the lungs of naive and Aspergillus fumigatus-infected mice. Med Mycol. 2010;48:303–9.

Atanasova R, Angoulvant A, Tefit M, Gay F, Guitard J, Mazier D, et al. A mouse model for Candida glabrata hematogenous disseminated infection starting from the gut: evaluation of strains with different adhesion properties. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69664.

Staab JF, Datta K, Rhee P. Niche-specific requirement for hyphal wall protein 1 in virulence of Candida albicans. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80842.

Hube B. From commensal to pathogen: stage- and tissue-specific gene expression of Candida albicans. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:336–41.

Fradin C, Kretschmar M, Nichterlein T, Gaillardin C, d’Enfert C, Hube B. Stage-specific gene expression of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1523–43.

Rosenbach A, Dignard D, Pierce JV, Whiteway M, Kumamoto CA. Adaptations of Candida albicans for growth in the mammalian intestinal tract. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:1075–86.

Perez JC, Kumamoto CA, Johnson AD. Candida albicans commensalism and pathogenicity are intertwined traits directed by a tightly knit transcriptional regulatory circuit. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001510.

Vale-Silva LA, Coste AT, Ischer F, Parker JE, Kelly SL, Pinto E, et al. Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Delta(5), (6)-desaturase gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1960–8.

Correia A, Lermann U, Teixeira L, Cerca F, Botelho S, da Costa RMG, et al. Limited role of secreted aspartyl proteinases Sap1 to Sap6 in Candida albicans virulence and host immune response in murine hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4839–49.

Barker KS, Park H, Phan QT, Xu L, Homayouni R, Rogers PD, et al. Transcriptome profile of the vascular endothelial cell response to Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:193–202.

Bader T, Schroppel K, Bentink S, Agabian N, Kohler G, Morschhauser J. Role of calcineurin in stress resistance, morphogenesis, and virulence of a Candida albicans wild-type strain. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4366–9.

Richards TS, Oliver BG, White TC. Micafungin activity against Candida albicans with diverse azole resistance phenotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:349–55.

Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311.

Hernandez-Santos N, Huppler AR, Peterson AC, Khader SA, McKenna KC, Gaffen SL. Th17 cells confer long-term adaptive immunity to oral mucosal Candida albicans infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:900–10.

Conti HR, Gaffen SL. Host responses to Candida albicans: Th17 cells and mucosal candidiasis. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:518–27.

Yano J, Kolls JK, Happel KI, Wormley F, Wozniak KL, Fidel PL Jr. The acute neutrophil response mediated by S100 alarmins during vaginal Candida infections is independent of the Th17-pathway. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46311.

Yano J, Noverr MC, Fidel PL Jr. Cytokines in the host response to Candida vaginitis: identifying a role for non-classical immune mediators, S100 alarmins. Cytokine. 2012;58:118–28.

Pietrella D, Rachini A, Pines M, Pandey N, Mosci P, Bistoni F, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 in protective immunity to vaginal candidiasis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22770.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Hu Bin for histopathological examination. This work was supported by National Key Basic Research Program of China (2013CB531605), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 81071332) and Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (BL2012003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Wang, C., Mei, H. et al. Combination of Estrogen and Immunosuppressive Agents to Establish a Mouse Model of Candidiasis with Concurrent Oral and Vaginal Mucosal Infection. Mycopathologia 181, 29–39 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-015-9947-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-015-9947-5