Abstract

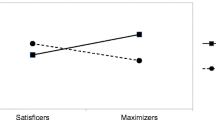

This article reports the influence of two specific consumption situations—hedonic and utilitarian—on the magnitude of the compromise effect. Based on the literatures of different valuation processes (valuation by calculation vs. valuation by feeling) and hedonic versus utilitarian consumption, the authors suggest that the compromise effect will be stronger under the utilitarian (vs. hedonic) consumption situation due to different valuation processes. Three experimental studies were conducted, and the results have supported the prediction. In addition, the authors successfully excluded alternative explanations such as differences in willingness to pay, justification, and attribute importance. The authors concluded with a discussion of the theoretical and managerial implication of this research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Three participants did not answer this question. However, other results were not changed by the inclusion/exclusion of three cases.

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for suggesting this alternative explanation.

This strategy was based on a similar procedure of Lee et al. (2008) and Kim et al. (2012), based on Spencer et al. (2005). Specifically, if the compromise effect under utilitarian consumption is mediated by different types of valuation, direct manipulation of different types of valuation should influence the magnitude of the compromise effect. If different types of valuation are not related to the compromise effect, then direct manipulation of different types of valuation should have no impact on the compromise effect.

Five participants did not answer this question. However, other results were not changed by the inclusion/exclusion of three cases.

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for suggesting these alternative explanations.

We do not argue that the different valuation processes are the only underlying mechanism for the strong compromise effect. Actually, part of the results of our study could be explained by other mechanisms, such as a self-regulatory focus. For example, the marginally significant compromise effect in the printer condition and valuation-by-feeling condition in study 2 could be driven by other mechanisms. However, we want to emphasize that the different valuation processes is one underlying mechanism for explaining all three empirical studies.

References

Batra, R., & Ahtola, O. (1990). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 159–170.

Botti, S., & McGill, A. L. (2011). The locus of choice: personal causality and satisfaction with hedonic and utilitarian decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(6), 1065–1078.

Chernev, A. (2004). Goal–attribute compatibility in consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1), 141–150.

Chernev, A. (2005). Context effects without a context: attribute balance as a reason for choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 213–223.

Devouges, W. H., Johnson, F. R., Dunford, R. W., Boyle, K. J., Hudson, S. P., & Wilson, K. N. (1992). Measuring nonuse damages using contingent valuation: an experimental evaluation of accuracy. Monograph 92–01, NC: Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park

Dhar, R., & Nowlis, S. M. (1999). The effect of time pressure on consumer choice deferral. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(4), 369–384.

Dhar, R., & Simonson, I. (2003). The effect of forced choice on choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(2), 146–160.

Dhar, R., Nowlis, S. M., & Sherman, S. J. (2000). Trying hard or hardly trying: an analysis of context effects in choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(4), 189–200.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101.

Hsee, C. K., & Rottenstreich, Y. (2004). Music, pandas, and muggers: on the affective psychology of value. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 133(1), 23–30.

Kahneman, D., & Ritov, I. (1999). Economic preferences or attitude expressions?: an analysis of dollar responses to public issues. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19(1/3), 203–235.

Khan, U., & Dhar, R. (2010). Price-framing effects on the purchase of hedonic and utilitarian bundles. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(6), 1090–1099.

Kim, J., Kim, J., & Park, J. (2012). Effects of cognitive resource availability on consumer decisions involving counterfeit products: the role of perceived justification. Marketing Letters, 23(3), 869–881.

Kivetz, R., & Simonson, I. (2002a). Earning the right to indulge: effort as a determinant of customer preferences toward frequency program rewards. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(2), 155–170.

Kivetz, R., & Simonson, I. (2002b). Self-control for the righteous: toward a theory of precommitment to indulgence. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(2), 199–217.

Larson, J. S., & Billeter, D. M. (2013). Consumer behavior in “equilibrium”: how experiencing physical balance increases compromise choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(4), 535–547.

Lee, H. J., Park, J., Lee, J. Y., & Wyer, R. S., Jr. (2008). Disposition effects and underlying mechanisms in e-trading of stocks. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 362–378.

Levav, J., Kivetz, R., & Cho, C. K. (2010). Motivational compatibility and choice conflict. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(3), 429–442.

Lin, C. H., Sun, Y. C., Chuang, S. C., & Su, H. J. (2008). Time pressure and the compromise and attraction effects in choice. Advances in Consumer Research, 35(3), 348–352.

Mourali, M., Böckenholt, U., & Laroche, M. (2007). Compromise and attraction effects under prevention and promotion motivations. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 234–247.

Okada, E. M. (2005). Justification effects on consumer choice of hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(1), 43–53.

Pham, M. (1998). Representativeness, relevance, and the use of feelings in decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(2), 144–159.

Pocheptsova, A., Amir, O., Dhar, R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Deciding without resources: psychological depletion and choice in context. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(3), 344–355.

Roy, R., & Ng, S. (2012). Regulatory focus and preference reversal between hedonic and utilitarian consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1), 81–88.

Simonson, I. (1989). Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 158–174.

Simonson, I., & Nowlis, S. M. (2000). The role of explanations and need for uniqueness in consumer decision making: unconventional choices based on reasons. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 49–68.

Simonson, I., & Tversky, A. (1992). Choice in context: tradeoffs contrast and extremeness aversion. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 281–295.

Spencer, S., Zanna, M., & Fong, G. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 845–851.

Strahilevitz, M., & Myers, J. (1998). Donations to charity as purchase incentives: how well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 434–446.

Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310–320.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Sungeun (Ange) Kim and Jungkeun Kim contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.(., Kim, J. The influence of hedonic versus utilitarian consumption situations on the compromise effect. Mark Lett 27, 387–401 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9331-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9331-0