Abstract

Introduction

The Welfare Act of 1996 banned welfare and food stamp eligibility for felony drug offenders and gave states the ability to modify their use of the law. Today, many states are revisiting their use of this ban, searching for ways to decrease the size of their prison populations; however, there are no empirical assessments of how this ban has affected prison populations and recidivism among drug offenders. Moreover, there are no causal investigations whatsoever to demonstrate whether welfare or food stamp benefits impact recidivism at all.

Objective

This paper provides the first empirical examination of the causal relationship between recidivism and welfare and food stamp benefits

Methods

Using a survival-based estimation, we estimated the impact of benefits on the recidivism of drug-offending populations using data from the National Corrections Reporting Program. We modeled this impact using a difference-in-difference estimator within a regression discontinuity framework.

Results

Results of this analysis are conclusive; we find no evidence that drug offending populations as a group were adversely or positively impacted by the ban overall. Results apply to both male and female populations and are robust to several sensitivity tests. Results also suggest the possibility that impacts significantly vary over time-at-risk, despite a zero net effect.

Conclusion

Overall, we show that the initial passage of the drug felony ban had no measurable large-scale impacts on recidivism among male or female drug offenders. We conclude that the state initiatives to remove or modify the ban, regardless of whether they improve lives of individual offenders, will likely have no appreciable impact on prison systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since the NCRP does not capture alternative measures of recidivism (e.g., rearrest, reconviction, incarceration in jail, etc), we could not explore alternative definitions in our analysis. However, return to prison is a useful and important measure (e.g., Hunt and Dumville 2016; Langen and Levin 2002; Durose et al. 2014). It is often used as a metric for evaluating programs, assessing trends and gauging impacts for other correctional issues of interest, often in concert with other metrics such as rearrest or reconviction (e.g., Bales et al. 2005; Spivak and Damphousse 2006; Steurer and Smith 2003).

The closest source to a nationally representative picture we could locate comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics Inmate Survey, which provides limited information on welfare receipt before an arrest and during an offender’s childhood. This survey does not track offenders over time.

In fact, there is explicit mention of trading benefits for drugs and the associated penalties in the SNAP benefit application form in Louisiana. (http://www.dcfs.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/searchable/EconomicStability/Applications/OFS4_4I.pdf).

The analysis of Butcher and LaLonde raises an interesting question of whether state agencies are in fact complying with the federal law. Though we cannot say with absolute certainty that every state complies, evidence gathered for this research (e.g., SNAP application forms asking about drug conviction status, and a conversation with a Massachusetts congressional representative) suggests that policies have resulted in operational changes at the agency level. (http://www.dcfs.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/searchable/EconomicStability/Applications/OFS4_4I.pdf).

Gabor and Botsko (1998) report that 10 states opted out of the ban on food stamps in the year following the PRWORA ban. Those results were based on a survey of states and only report responses for the food stamp portion of the ban. Our independent research has led us to conclude that only 4 states had fully opted out of both aspects of the ban (i.e. completely removed restrictions to both SNAP and TANF).

Broadly, states adopt three types of partial reforms: (1) requirements for offenders to participate in or complete treatment before receiving benefits; (2) allowance for drug offenders who committed less serious crimes to access benefits; and (3) allowance for offenders to receive benefits after a probationary period following release.

New York has data back going back to 1994, but opted out immediately after the ban was passed. We separately tested our pooled estimation with and without New York and found no difference in findings between models.

Apparent confusion by states as to what is meant by “ban modification” has led to reporting error in the State Options Report, and subsequently, confusion in the literature as to what states have adopted what policies and when. For example, although Iowa imposes some drug rehabilitation services (or other requirements) for former drug felons, FNS reports show it has opted out since 2006.

A large number of studies have used date/time as an assignment variable modeled within an RD framework. Table 5 in Lee and Lemieux (2010) provides a nice summary of many such studies. Because time is the forcing variable, our approach can also be described as an “event study”—language more common to various social science disciplines.

We argue that prison admission is a good proxy for date of conviction. Prior to conviction, most offenders are housed in jails rather than prisons. After conviction, most offenders are moved to prison quickly.

<15% of offenders in our analytic sample are convicted of more than two offenses and, of these, <2% have nondrug offenses for their first two offenses and a drug-related offense for their third offense. Since we cannot know whether this third offense is a felony or misdemeanor, we treat these cases as nondrug offenders.

For reference, computations of detectable effects performed in Stata (using the stpower command) show that sample sizes of 200, 500, 3,000, and 10,000 can detect minimum differences in recidivism rates of roughly 0.40, 0.25, 0.10, and 0.05 respectively. These computations assume a two-sided test of a Cox model where the standard deviation of the Ban/Mod covariate is 0.5, power is 0.8, and alpha is 0.05.

We also conducted empirical tests of impacts excluding Florida and Minnesota. Results from these tests did not change the core findings of this paper.

The difference in the sum of the squared residuals between these competing trends is <0.0001.

Results are available upon request.

This paper proposes one alternative construction for a “new crime” using a time-based rule that classifies all prison admissions as new crimes when no release from prison has been observed within the prior year. We test the sensitivity of our results to this classification rule (as well as a 3-year variant of this rule) and find no discernable difference in our findings.

References

Allard P (2002) Life sentences: denying welfare benefits to women convicted of drug offenses. The Sentencing Project, Washington, DC https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/03-18-03atriciaAllardReport.pdf

Allison PD (2010) Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide, 2nd edn. Cary, SAS Institute

Angrist J (2006) Instrumental variables methods in experimental criminological research: what, why and how. J Exp Criminol 2:23–44

Angrist J, Pischke J, Pischke J (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion, vol 1. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bales W, Bedard LE, Quinn ST, Ensley DT, Holley GP (2005) Recidivism of public and private state prison inmates in Florida. Criminol Public Policy 4:57–82

Bitler M (2014) The health and nutrition effects of SNAP: selection into the program and a review of the literature on its effects. University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, DP2014-02. http://www.ukcpr.org/Publications/DP2014-02.pdf

Blank RM (2002) Evaluating welfare reform in the United States (NBER No. w8983). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w8983

Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (1993) Environment, routine, and situation: toward a pattern theory of crime. In: Clarke RV, Felson M (eds) Routine activity and rational choice: advances in criminological theory, vol 5, transaction. New Brunswick, NJ, pp 259–294

Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (1995) Criminality of place. Eur J Crim Policy Res 3:5–26

Bushway, S. D., Stoll, M. A., and Weiman, D. (Eds.). (2007). Barriers to reentry? The Labor Market for Released Prisoners in Post-Industrial America. Russell Sage Foundation. Doi:10.1177/0038038509351628

Butcher KF, LaLonde R (2006) Female offenders’ use of social welfare programs before and after jail and prison: does prison cause welfare dependency? FRB of Chicago Working Paper No. 2006-13. Doi:10.2139/ssrn.949179

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cohen Lawrence E, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

Durose MR, Cooper AD, Snyder HN (2014) Recidivism of prisoners released in 30 states in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rprts05p0510.pdf

Eadler L (2011). Purging the drug conviction ban on food stamps in California. Scholar 14(117): 117–164. http://lawspace.stmarytx.edu/items/show/1504

Eck JE, Weisburd DL (2015) Crime places in crime theory. Crime and Place: Crime Prevention Studies 4:1–33

Edgemon E (2015) Alabama drug felons to get welfare benefits after 2 decade ban. http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2015/06/alabama_drug_felons_wait_for_n.html

Ekstrand L (2005) Various factors may limit the impacts of federal laws that provide for denial of selected benefits. United States Government Accountability Office, Washington, DC. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05238.pdf

Evans DN (2014) The debt penalty. Research and Evaluation Center, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York. http://www.justicefellowship.org/sites/default/files/The%20Debt%20Penalty_John%20Jay_August%202014.pdf

Gabor V, Botsko C (1998). State food stamp policy choices under welfare reform: Findings of 1997 50-state survey. US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, Alexandria, VA. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/finsum.pdf

Gaes GG, Luallen J, Rhodes W, Edgerton J (2016) Classifying prisoner returns: a research note. Justice Res Policy 17(1):48–70

Geller A, Curtis MA (2011) A sort of homecoming: incarceration and the housing security of urban men. Soc Sci Res 40:1196–1213. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1632578

Gelman A, Imbens G (2014). Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. NBER No. w20405. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Godsoe C (1998) The ban on welfare for felony drug offenders: giving a new meaning to life sentence. Berkeley Women’s Law J 13: 257–267. http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1145&context=bglj

Hirsch AE (1999) Some days are harder than hard: welfare reform and women with drug convictions in Pennsylvania. Center for Law and Social Policy, Washington, DC. http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/files/0167.pdf

Holtfreter K, Reisig M, Morash M (2004) Poverty, state capital, and recidivism among women offenders. Criminol Public Policy 3:185–208. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2004.tb00035.x

Hunt KS, Dumville R (2016) Recidivism among federal offenders: a comprehensive overview. US Sentencing Commission, Washington

Imbens GW, Lemieux T (2008) Regression discontinuity designs: a guide to practice. J Econom 142:615–635

Jacob R, Zhu P, Somers MA, Bloom H (2012) A practical guide to regression discontinuity. MDRC

Johnson BD, Goldstein PJ, Preble E, Schmeidler J, Lipton DS, Spunt B, Miller T (1985) Taking care of business: the economics of crime by heroin abusers, Lexington Books: Lexington. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2578963

Klein JP, Moeschberger ML (2003) Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. Springer, Berlin

Kling JR (2006) Incarceration length, employment, and earnings. Am Econ Rev 96:863–876. doi:10.3386/w12003

Langen P, Levin D (2002) Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Burueau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Lattimore PK, Steffey DM, Visher CA (2009). Prisoner reentry experiences of adult males: characteristics, service receipt, and outcomes of participants in the SVORI Multi-site Evaluation, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/230419.pdf

Lechner M (2010) The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference methods. Universitat St. Gallen, Discussion Paper 2010-28. http://ux-tauri.unisg.ch/RePEc/usg/dp2010/DP-1028-Le.pdf

Lee DS, Lemieux T (2010) Regression discontinuity designs in economics. J Econ Lit 48:281–355

Lindner SR, Nichols A (2012) The impact of temporary assistance programs on disability rolls and re-employment. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper 2012-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1993310

Lindquist CH, Lattimore PK, Barrick K, Visher CA (2009) Prisoner reentry experiences of adult females: characteristics, service receipt, and outcomes of participants in the SVORI multi-site evaluation. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/230420.pdf

Luallen J, Neary K, Kling R, Rhodes B, Gaes G, Rich T (2012) A description of computing code used to identify correctional terms and histories. Abt Associates Inc. NCRP White Paper #3, Cambridge, MA

Mauer M (2002) Introduction: the collateral consequences of imprisonment. Fordham Urban Law J 30:1491. http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/frdurb30anddiv=64andid=andpage

Mauer M, McCalmont V (2013) A lifetime of punishment: the impact of the felony drug ban on welfare benefits. The Sentencing Project, Washington, DC. http://www.ushrnetwork.org/sites/ushrnetwork.org/files/alifetimeofpunishment.pdf

Mohan L, Lower-Basch E (2014, updated 2017) No more double punishments. CLASP, Washington, DC. http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Safety-Net-Felony-Ban-FINAL.pdf

Neal D, Rick A (2014) The prison boom and the lack of black progress after Smith and Welch (NBER No. w20283). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996 § 115, 42 USC § 862a. (1996)

Petersilia J (2003) When prisoners come home: parole and prisoner reentry. Oxford University Press, Oxford. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195160864.001.0001

Pfaff JF (2011) The myths and realities of correctional severity: evidence from the national corrections reporting program on sentencing practices. Am Law Econ Rev 13:491–531

Rhodes W, Gaes G, Rich T, Almozlino Y, Astion M, Kling R, Luallen J, Neary K, Shively M (2012). Observations on the NCRP. NCRP White Paper #1. Abt Associates, Cambridge. https://www.ncrp.info/LinkedDocuments/NCRP% 20White%20Paper%20No%201%20Observations%20on%20NCRP.9%204%202012.pdf

Roebuck V (2014) The methods to prevent and detect fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Stevenson Univ Forensics J. 5: 14–19. http://www.stevenson.edu/graduate-professional-studies/publications/forensics/documents/forensic-journal-2014.pdf

Schoeni RF, Blank RM (2000) What has welfare reform accomplished? Impacts on welfare participation, employment, income, poverty, and family structure (NBER No. w7627). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge. doi:10.3386/w7627

Sheely A, Kneipp SM (2015) The effects of collateral consequences of criminal involvement on employment, use of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and health. Women Health 55:548–565. doi:10.1080/03630242.2015.1022814

Spivak AL, Damphousse KR (2006) Who returns to prison? A survival analysis of recidivism among adult offenders released in Oklahoma, 1985–2004. Justice Res Policy 8:57–88

Statement of the Honorable Phyllis K. Fong Inspector General before the US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, 112th Congress 1–7 (2012) (testimony of Phyllis K. Fong). http://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/IGtestimony140305.pdf

Steurer SJ, Smith LG (2003) Education reduces crime: three-state recidivism study. Executive summary. http://www.ceanational.org/PDFs/EdReducesCrime.pdf

Stoll MA, Bushway SD (2008) The effect of criminal background checks on hiring ex-offenders. Criminol Public Policy 7:371–404. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2008.00515.x

Travis J (2005) But they all come back: facing the challenges of prisoner reentry. Urban Institute, New York. doi:10.5860/choice.43-1271

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2016, August 16) State Options Report. Retrieved April 10, 2017, from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-options-report

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2017, April 07) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Retrieved April 10, 2017, from https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

United States Department of Health and Human Services (2016, October 18) Data and reports. Retrieved April 10, 2017, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/data-reports

Western B, Braga AA, Davis J, Sirois C (2014) Stress and hardship after prison. Am J Sociol 120:1512–1547. doi:10.1086/681301

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant Nos. 2010-BJ-CX-K067 and 2015-R2-CX-K135 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice. For this work, Thomas Rich served as Project Director along with Principal Investigators William Rhodes and Gerry Gaes. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the US Department of Justice. The authors are responsible for any errors in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

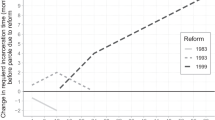

See Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luallen, J., Edgerton, J. & Rabideau, D. A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of the Impact of Public Assistance on Prisoner Recidivism. J Quant Criminol 34, 741–773 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9353-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9353-x