Abstract

Objectives

To test the liberation hypothesis in a judicial context unconstrained by sentencing guidelines.

Methods

We examined cross-sectional sentencing data (n = 17,671) using a hurdle count model, which combines a binary (logistic regression) model to predict zero counts and a zero-truncated negative binomial model to predict positive counts. We also conducted a series of Monte Carlo simulations to demonstrate that the hurdle count model provides unbiased estimates of our sentencing data and outperforms alternative approaches.

Results

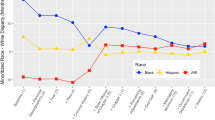

For the liberation hypothesis, results of the interaction terms for race x offense severity and race x criminal history varied by decision type. For the in/out decision, criminal history moderated the effects of race: among offenders with less extensive criminal histories blacks were more likely to be incarcerated; among offenders with higher criminal histories this race effect disappeared. The race x offense severity interaction was not significant for the in/out decision. For the sentence length decision, offense severity moderated the effects of race: among offenders convicted of less serious crimes blacks received longer sentences than whites; among offenders convicted of crimes falling in the most serious offense categories the race effect became non-significant for Felony D offenses and transitioned to a relative reduction for blacks for the most serious Felony A, B, and C categories. The race x criminal history interaction was not significant for the length decision.

Conclusions

There is some support for the liberation hypothesis in this test from a non-guidelines jurisdiction. The findings suggest, however, that the decision to incarcerate and the sentence length decision may employ different processes in which the interactions between race and seriousness measures vary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Several researchers have also suggested integrating focal concerns with the liberation hypothesis. Lieber and Blowers (2003) took a first step in their study of misdemeanor sentencing. They note that while the liberation hypothesis gives a reason why sentiments are more influential at lower levels of severity, the hypothesis does not offer an explanation why those sentiments might manifest as racial bias. Lieber and Blowers (2003) turn to focal concerns to bridge this gap. Ball (2006) also paired focal concerns with the liberation hypothesis in his study of prosecutorial plea bargaining, and Guevara et al. (2011) suggest further integration of focal concerns and attributional theory as a path for future research.

During FY2001, lower level magistrate courts had jurisdiction to sentence offenses subject to a maximum 30 days incarceration, a $500 fine, or both; or up to one year in prison, a $5500 fine, or both upon transfer from the Circuit Court (S.C. Code §§ 22-3-550, -545). Criminal jurisdiction for all other cases rested with the Circuit Courts (S.C. Code § 14-25-65). The Commission data did not contain a record of all misdemeanor offenders sentenced in the lower courts. Because neither the complete population nor a representative sample of misdemeanor offenders was available, it was not possible to examine the universe of misdemeanor and felony sentencing outcomes. Accordingly, we included all felonies and serious misdemeanors carrying the potential for more than one-year incarceration, which is the traditional definition of a felony offense (McAninch, et al. 2007). This allowed us to include offenses which were deemed serious enough by the S.C. legislature to merit the potential for more than a year in prison, while also removing the unrepresentative portion of misdemeanor offenses that happened to have been sentenced in Circuit Court rather than a lower-level court. Classifying offenses this way also makes these analyses more comparable to the existing research on felony sentencing conducted in other states, rather than constituting a study marked by anomalous state law designations.

While misdemeanors with potential prison sentences of more than one year were included as the lowest offense severity level, we recoded the unclassified common law offenses which were subject to 10 year maximums as Class E felonies because Class E felonies were capped at a maximum of 10 years (S.C. Code Ann. Sections 17-25-20, 17-25-30; McAninch et al. 2007).

Starting with the supplemental Court Administration list of all criminal cases that went to trial in FY2001, we successfully matched 85 % of these (260 of 306 total trials) with the Commission data. Some of the failed matches were sealed cases listed in the supplemental Court Administration data that might have been excluded from the Commission’s dataset, while other cases failed to match for unknown reasons.

We were not able to discern between prison and jail sentences. Defendants sentenced to more than three months custodial time are processed into the state correctional system; defendants given less than three months serve their time in local jails or detention centers. Thus, unlike in some states, Circuit Court judges do not make an independent decision whether to send incarcerated offenders to a local jail or central prison—that decision is a product of the length of the sentence imposed.

The expected minimum sentence was chosen over other alternatives because offenders might have been eligible for parole after serving 25, 33, or 85 % of their sentences, or may never have been eligible, depending upon the classification of the offense. Using the expected minimum rather than the imposed maximum accounted for these differences in parole eligibility (Chiricos and Bales 1991; Gertz and Price 1985; Spohn and Cederblom 1991). The expected minimum was calculated by adjusting the imposed maximum sentence by a parole eligibility multiplier as determined by the controlling offense (e.g., 0.25, 0.33, 0.85, 1.0) and rounded up to the nearest month (<200 of the 17,671 original sentences are non-integers). For example, if an offender was sentenced to 10 years and fell under the 25 percent parole eligibility designation, the expected minimum would be 2.5 years (10 × 0.25), or 30 months.

Choosing a cut-point for the top coding is somewhat arbitrary, and some scholars have used other operationalizations (e.g., Johnson et al. 2008, top coded at 470 months based on the federal sentencing commission’s convention of using 470 months as representative of a life sentence). Our findings were robust to other coding decisions. For example, we ran supplemental models that altered the value of right-censoring, omitted life and death sentences altogether, and used the unmodified (raw) sentence, and our substantive findings were not meaningfully different across models.

Note that the commitment score was constructed post hoc by the Commission and thus was not available to or considered by the sentencing judge. It is included as a proxy to measure the nature and number of offenses for those individuals sentenced after pleading guilty or being found guilty of multiple offenses, which are not otherwise accounted for, but which likely would be considered by the sentencing judge.

To address potential selection bias in this two-stage modeling, scholars sometimes incorporate a Heckman correction (e.g., Nobiling et al. 1998; Steffensmeier and Demuth 2001; Ulmer and Johnson 2004). However, Bushway, Johnson, and Slocum (2007) note that the execution of the Heckman correction in sentencing studies has been highly problematic. Among the most serious problems is the near ubiquitous failure to incorporate an exclusion restriction, which requires at least one variable that affects the selection process but not the substantive equation of interest. As a result, Bushway and colleagues caution that employing the Heckman correction may cause more harm than good in many instances. Since the Bushway et al. (2007) article was published, many scholars have considered but not reported Heckman corrected models (e.g., Doerner and Demuth, 2010; Johnson et al. 2008; Lieber and Johnson 2008; Ulmer et al. 2010). Were we to estimate an OLS model rather than the one we introduce here, we would also proceed without a Heckman correction because (1) we are unable to identify an exclusion restriction; and (2) the condition number for our independent variables, including interaction terms, is well above the suggested rule of thumb of 20 (see Bushway et al. 2007: 168–169).

For our sentencing data we found evidence that an OLS model would indeed violate the assumption of homoscedasticity. Informal plots of the residuals versus fitted values and formal tests for heteroscedasticity such as Cameron and Trivedi’s decomposition of IM-test, White’s General Test, and the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg Test detect heteroscedasticity indicate that the null hypothesis of constant error variance has been violated. Further, while logging the dependent variable does reduce heteroscedasticity in our data, we still find significant levels in diagnostic plots and tests of the transformed criminal sentence.

Even the combination of minimal values for offense seriousness and criminal history leads to a non-trivial probability of incarceration, as the proportion of those sentenced to prison with these attributes is 0.034. A zero-inflated model might be appropriate in the sentencing context, however, where the data also included infractions for which active incarceration was never an option. We also note that Anderson, Kling, and Stith (1999) used a zero-inflated negative binomial model to examine inter-judge disparity before and after the federal sentencing guidelines became binding.

The R replication code is available upon request.

For purposes of comparison, we specified three different counts models—the Poisson Regression Model (PRM), Negative Binomial Regression Model (NBRM), and the HRM-NB—to determine the best fit for our sentencing data. For the HRM-NB model, we used the same set of predictors for the incarceration decision as we did for the truncated sentencing count. First, we calculated mean predicted probabilities for each model, and then created a difference measure of the observed and predicted counts (Long and Freese 2014). The ideal model would be one in which all plot points fall at 0, as this would indicate that our model perfectly predicted the observed data (i.e., observed – predicted = 0). The HRM-NB fit the data best, hovering closely around the reference line at zero. Second, because the NBRM reduces to the PRM when the overdispersion parameter, α, is equal to zero, a Likelihood Ratio (LR) test of the null hypothesis (H 0 : α = 0) can be conducted. In our case, α > 0, and the resulting high value for the χ 2 statistic led us to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the NBRM should be preferred over the PRM. Third, Greene (1994) proposes using a Vuong test (V) for non-nested models like the NBRM and the HRM-NB. If V > 1.96, the first model is preferred; if V < −1.96, the second model provides a better fit. Using guidance provided by Long and Freese (2014), we computed V for the PRM vs. HRM-NB, as well as the NBRM vs. HRM-NB. The results of the Vuong test strongly support the HRM-NB over alternative count models such as the PRM and the NBRM, as V is well below the specified cutoff of −1.96.

We also have data on the judge responsible for the sentencing decision for more than 99 % of the cases in our data, which is important as we would expect sentencing decisions to be clustered by judge. Moulton (1990) demonstrates that failure to properly account for clustering can lead to massive underestimation of standard errors and flawed hypothesis tests.

For a dummy variable, the AME is the mean of differences in predictions for each observation (leaving all other values unchanged in the data) when moving from 0 to 1 for that variable. For example, the marginal effect of race for a single observation is the difference in the predicted number of months sentenced to prison assuming that the offender’s race was first coded as ‘white’ and then as ‘black’. To obtain the AME, we simply take the mean of these individual marginal effects, which allows us to compare the effect of race for two hypothetical populations—one all black and one all white—on criminal sentencing decisions (for more information about marginal effects, see Williams, 2012). For a continuous variable, the AME is the mean of instantaneous rates of change—that is, the mean of the slopes—at each value of the variable over all observations (leaving the rest of the data unchanged). Thus, the AME for a continuous variable provides a good approximation for the amount of change in Y given a 1-unit change in X i .

We also specified a generalized negative binomial model using the gnbreg command in Stata which allowed us to explicitly model the predictors that contribute to ovedispersion in the count response. We discovered that many of the case characteristics—but not offender attributes—account for overdispersion: offense seriousness, type of offense (drug, property, and other), trial, and mandatory minimum are significant predictors.

For the main effects of history in the dummy-coded model, the no-history group appeared to receive longer average sentences than some of the other categories. This seems counterintuitive, but most offenders with no criminal history would not be expected to be imprisoned in the first place; for those first offenders who were sent to prison, it is possible that some aspect of the case or offender that led to the exceptional disposition of prison (e.g., harm to victim, the demeanor or attitude of the defendant, etc.), also resulted in a comparatively punitive sentence length. Where differences were statistically significant, they were modest at best. Results are available upon request from the first author.

References

Albonetti CA (1991) An integration of theories to explain judicial discretion. Soc Probl 38:247–266

Anderson JM, Kling JR, Stith K (1999) Measuring interjudge sentencing disparity: before and after the federal sentencing guidelines. J Law Econ 42:271–308

Baldus DC, Pulaski C, Woodworth G (1983) Comparative review of death sentences: an empirical study of the Georgia experience. J Crim Law Criminol 74:661–753

Baldus DC, Woodworth G, Pulaski CA (1990) Equal justice and the death penalty: a legal and empirical analysis. Upne, Lebanon

Ball JD (2006) Is it a prosecutor’s world? Determinants of count bargaining decisions. J Contemp Crim Justice 22(3):241–260

Barkan SE, Cohn SF (1998) Racial prejudice and support by whites for police use of force: a research note. Justice Q 15(4):743–753

Baumer EP (2013) Reassessing and redirecting research on race and sentencing. Justice Q 30(2):231–261

Blumer H (1969) Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Blumstein A (1982) On the racial disproportionality of United States’ prison populations. J Crim l Criminol 73:1259

Blumstein A (1993) Racial disproportionality of US prison populations revisited. U Colo l Rev 64:743

Bushway SD, Piehl AM (2001) Judging judicial discretion: legal factors and racial discrimination in sentencing. Law Soc Rev 35:733–764

Bushway S, Johnson BD, Slocum LA (2007) Is the magic still there? The use of the Heckman two-step correction for selection bias in criminology. J Quant Criminol 23(2):151–178

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2013) Regression of count data, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Carsey Thomas M, Harden Jeffrey J (2014) Monte carlo simulation and resampling methods for social science. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Chen EY (2008) The liberation hypothesis and racial and ethnic disparities in the application of California’s three strikes law. J Ethn Crim Justice 6(2):83–102

Chiricos TG, Bales WD (1991) Unemployment and punishment: an empirical assessment. Criminology 29:701–724

Chiricos TG, Crawford C (1995) Race and imprisonment: a contextual assessment of the evidence. In: Hawkins DF (ed) Ethnicity, race, and crime: perspectives across time and space. State University of New York Press, Albany

Doerner JK, Demuth S (2010) The independent and joint effects of race/ethnicity, gender, and age on sentencing outcomes in US federal courts. Justice Q 27(1):1–27

Eisenstein J, Flemming RB, Nardulli PF (1988) The contours of justice: communities and their courts. Little, Brown, Boston

Engen RL (2009) Assessing determinate and presumptive sentencing—making research relevant. Criminol Public Policy 8(2):323–336

Engen RL, Gainey RR (2000) Modeling the effects of legally relevant and extralegal factors under sentencing guidelines: the rules have changed. Criminology 38(4):1207–1230

Fischman JB, Schanzenbach MM (2012) Racial disparities under the federal sentencing guidelines: the role of judicial discretion and mandatory minimums. J Empir Leg Stud 9(4):729–764

Frase RS (2009) What explains persistent racial disproportionality in Minnesota’s prison and jail populations? Crime Justice 38(1):201–280

Freiburger TL, Hilinski CM (2013) An examination of the interactions of race and gender on sentencing decisions using a trichotomous dependent variable. Crime Delinq 59(1):59–86

Gertz MG, Price AC (1985) Variables influencing sentencing severity: intercourt differences in Connecticut. J Crim Justice 13(2):131–139

Grattet R, Lin J (2014) Supervision intensity and parole outcomes: a competing risks approach to criminal and technical parole violations. Justice Q (epub ahead of print)

Greene WH (1994) Accounting for excess zeros and sample selection in poisson and negative binomial regression models (March 1994). NYU Working Paper No. EC-94-10. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1293115

Guevara L, Boyd LM, Taylor AP, Brown RA (2011) Racial disparities in juvenile court outcomes: a test of the liberation hypothesis. J Ethn Crim Justice 9(3):200–217

Hilbe JM (2014) Modeling count data. Cambridge University Press, New York

Johnson BD (2012) Cross-classified multilevel models: an application to the criminal case processing of indicted terrorists. J Quant Criminol 28(1):163–189

Johnson BD, Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (2008) The social context of guidelines circumvention: the case of federal district courts. Criminology 46(3):737–783

Kalven H, Zeisel H, Callahan T, Ennis P (1966) The American jury. Little, Brown, Boston, p 498

Kautt PM, Delone MA (2006) Sentencing outcomes under competing but coexisting sentencing interventions: untying the Gordian knot. Crim Justice Rev 31(2):105–131

King G (1988) Statistical models for political science event counts: bias in conventional procedures and evidence for the exponential poisson regression model. Am J Polit Sci 32:838–863

Kramer J, Ulmer J (2009) Sentencing guidelines: lessons from Pennsylvania. Lynne Rienner, Boulder

Kutateladze BL, Andiloro NR, Johnson BD, Spohn CC (2014) Cumulative disadvantage: examining racial and ethnic disparity in prosecution and sentencing. Criminology 52(3):514–551

Lambert D (1992) Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics 34(1):1–14

Leiber MJ, Blowers AN (2003) Race and misdemeanor sentencing. Crim Justice Policy Rev 14(4):464–485

Leiber MJ, Johnson JD (2008) Being Young and Black what are their effects on juvenile justice decision making? Crime Delinq 54(4):560–581

Levin MA (1977) Urban politics and the criminal courts. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lin J, Grattet R, Petersilia J (2012) Justice by other means: venue sorting in parole revocation. Law Policy 34(4):349–372

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables, Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences, vol 7. SAGE Publications

Long JS, Freese J (2014) Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. Stata press, College Station

MacDonald JM, Lattimore PK (2010) Count models in criminology. In: Piquero AR, Weisburd D (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, New York, pp 683–698

McAninch WS, Fairey FW, Coggiola LM (2007) The criminal law of South Carolina, 3rd edn. South Carolina Bar, Columbia

Mitchell O (2005) A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. J Quant Criminol 21(4):439–466

Moulton BR (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72:334–338

Mullahy J (1986) Specification and testing of some modified count data models. J Econ 33(3):341–365

Mustard DB (2001) Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: evidence from the us federal courts. J Law Econ 44(1):285–314

Nobiling T, Spohn C, Delone M (1998) A tale of two counties: unemployment and sentence severity. Justice Q 15:459–485

Rehavi MM, Starr SB (2014) Racial disparity in federal criminal sentences. J Polit Econ 122(6):1320–1354

Reitz KR (2009) Demographic impact statements, O’Connor’s warning, and the mysteries of prison release: topics from a sentencing reform agenda. Fla Law Rev 61:683

Santos Silva JMC, Tenreyo S (2006) The log of gravity. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):641–658

Spohn C (2000) Thirty years of sentencing reform: the quest for a racially neutral sentencing process. In: National Institute of Justice: criminal justice 2000. National Institute of Justice, Washington

Spohn C (2009) How do judges decide? The search for justice and fairness in punishment, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Spohn C, Cederblom J (1991) Race and disparities in sentencing: a test of the liberation hypothesis. Justice Q 8:305–327

Spohn C, DeLone M (2000) When does race matter?: an analysis of the conditions under which race affects sentence severity. Sociol Crime Law Deviance 2:3–37

Starr S (2015) Estimating gender disparities in federal criminal cases. Am L Econ Rev 17(1):127–159

Steffensmeier D, Demuth S (2000) Ethnicity and sentencing outcomes in US federal courts: who is punished more harshly? Am Sociol Rev 65:705–729

Steffensmeier D, Demuth S (2001) Ethnicity and judges’ sentencing decisions: hispanic-black-white comparisons. Criminology 39(1):145–178

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer J, Kramer J (1998) The interaction of race, gender and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black and male. Criminology 36(4):763–797

Tonry M (1995) Malign neglect: race, crime, and punishment in America. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tonry M (1996) Sentencing matters. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ulmer JT (1997) Social worlds of sentencing: court communities under sentencing guidelines. SUNY Press, New York

Ulmer JT (2012) Recent developments and new directions in sentencing research. Justice Q 29(1):1–40

Ulmer JT, Johnson B (2004) Sentencing in context: a multilevel analysis. Criminology 42(1):137–178

Ulmer JT, Eisenstein J, Johnson BD (2010) Trial penalties in federal sentencing: extra-guidelines factors and district variation. Justice Q 27(4):560–592

Warren P, Chiricos T, Bales W (2012) The imprisonment penalty for young Black and Hispanic males a crime-specific analysis. J Res Crime Delinq 49(1):56–80

Williams R (2012) Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J 12(2):308–331

Wooldredge JD (2007) Neighborhood effects on felony sentencing. J Res Crime Delinq 44(2):238–263

Zatz MS (2000) The convergence of race, ethnicity, gender, and class on court decisionmaking: looking toward the 21st century. In: Policies, processes, and decisions of the criminal justice system, vol 3. US Department of Justice, Washington, DC, pp 503–552

Zorn CJ (1996) Evaluating zero-inflated and hurdle Poisson specifications. Midwest Polit Sci Assoc 18(20):1–16

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hester, R., Hartman, T.K. Conditional Race Disparities in Criminal Sentencing: A Test of the Liberation Hypothesis From a Non-Guidelines State. J Quant Criminol 33, 77–100 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9283-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9283-z