Abstract

French mathematician Michel Chasles (1793–1880), a staunch defender of pure geometrical methods, is now mostly remembered as the author of the Aperçu historique (1837). In this book, he retraced the history of geometry in order to expound epistemological theses on what constitutes a virtuous practice of geometry. Amongst these stands out the assertion that the values of generality and simplicity in mathematics are intimately connected. In this paper, we flesh out this claim by analysing Chasles’s geometrical solutions to the century-old problem of the attraction of the ellipsoids. We show how these solutions echo Chasles’s evaluation of the relative strengths of geometrical and analytical methods, and how they embody a set of normative rules for the geometer’s practice whose observance Chasles deemed necessary and sufficient for the development of general methods and theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Or masses, if these ellipsoids are taken to be of homogeneous density. To abbreviate and simplify expressions, in this paper, we will only consider homogeneous ellipsoids of density \(\rho = 1\), and omit this term when reproducing equations and formulas.

See Grabiner (1997) for more on the context of MacLaurin’s reception in continental Europe.

A longitudinal study of the history of mechanics following this particular problem would probably give rise to a finer picture of the fluctuation of disciplinary and epistemological boundaries between geometry, algebra, and mechanics. Indeed, the computational difficulties this problem entails, and the rich geometrical interpretations it allows, make it a robust and abundant source for reflections and discussions. Therefore, it is no surprise that such a picture would include the works of most of the mathematicians usually associated with the development of mechanics: D’Alembert, Legendre, Poisson, … all worked at some point in their career on the attraction of ellipsoids. Even far into the twentieth century, mathematical physicists continued to go back to this problem for renewed insights (see, for instance, Arnold 1985).

In first approximation, analytical geometry here refers to geometry done with the help of Cartesian coordinates, and algebraic or infinitesimal calculus. Pure geometry, on the other hand, is geometry done without such tools. We will go back to this distinction later in the paper, and explain how such crude distinctions do not really capture the disciplinary and epistemological boundaries that actors such as Chasles identify with these terms.

The complete title of this book translates into “General historical survey of the origin and development of methods in geometry, in particular of those that relate to modern geometry, followed by a memoir of geometry on two general principles of that science, that is, duality and homography”. To a large extent, this text will constitute our main source to study Chasles’s early epistemology and practice of geometry, which substantially evolves in his later works, as he obtained a chair at the Sorbonne where he developed and taught what he called “Higher Geometry” (see Chasles 1852).

Let us here remember that, when he died, Chasles was a member of most European academies, the first foreign recipient of the Copley medal, and had been teaching at the Sorbonne for several decades. In a obituary published in the New York Times shortly after his death, he is even said to be “the most distinguished mathematician in France”. However, his fame quickly declined over the decades following his death. The reasons for this decline are still unclear. Possible explanations include the infamous Vrain-Lucas affair, by which he was publicly ridiculed and which left a lasting mark on the collective memory of his life, but also the celebration of other nineteenth-century geometers such as Poncelet or Von Staudt as the main protagonists of the development of projective geometry in subsequent historical narratives.

In his general history of nineteenth geometry, (Gray 2007) acknowledges that “[r]esearch needs to be done on Chasles’ presentation of projective geometry, and the way his work eclipsed that of Poncelet” (Introduction, p. 7). Recent attempts to do just so include Nabonnand (2006) and Chemla (2016). Despite the fact that several of Chasles’s first successful scientific contributions dealt with mechanics (whether it be with kinematics or, in our case, the theory of attraction), and that Chasles taught mechanics at the École polytechnique between 1841 and 1851, his work is rarely mentioned in more than passing footnotes in general studies in the history of mechanics. See for instance Grattan Guinness (1990).

See for instance Borgnet (1840), Catalan (1841), Hoppé (1863), Peslin (1843) among many others. Bertrand (1892, 8), in a eulogy pronounced a dozen years after Chasles’s death, asserts that these proofs of MacLaurin’s theorem have become “classics”, taught by most professors who desire to teach this subject. To what extent this claim is truthful, however, remains unclear.

Chasles himself acknowledges it, see Chasles (1846, 640).

In that respect, these proofs yield rich insights into the practice of re-proving, a practice which has been studied in detail in Dawson (2015).

Such a claim is far from being unique in the history of mathematics. For instance, in his autobiography, Récoltes et semailles, French mathematician Alexandre Grothendieck makes constant use of the notion of “childish simplicity” (“simplicité enfantine”), which he uses to describe extremely complex theorems, precisely because of their perceived generality. See McLarty (2003) for more on that issue.

We will mainly focus on Chasles’s Aperçu historique; a more detailed description thereof, with special emphasis on the theme of generality, can be found in Chemla (2016), from which some of the examples discussed below are borrowed. Several shifts occur after a chair of Higher Geometry was created at the Sorbonne for Chasles, which we do not discuss here.

“Nous avons eu en vue surtout, en retraçant la marche de la Géométrie, et en présentant l’état de ses découvertes et de ses doctrines récentes, de montrer, par quelques exemples, que le caractère de ces doctrines est d’apporter, dans toutes les parties de la science de l’étendue, une facilité nouvelle et les moyens d’arriver à une généralisation, jusqu’ici inconnue, de toutes les vérités géométriques” (Chasles 1837a, 2).

This mathematical habitus can be detected in many other works from that period and that milieu, such as Lacroix’s Traité du calcul différentiel (1797/8), or Fourier’s Théorie analytique de la chaleur (1822).

This project was eventually dropped, but gave Chasles the initial content for the redaction of several notes.

It is also likely that the entire Note V (pp. 288–290) is directed against Comte’s tenth Leçon, where Geometry is defined a the science of the measurement of extension, which Chasles very much refused.

Note that this criticism does not apply equally to the whole of Ancient geometry. For instance, Apollonius seems somewhat immune to it, as Chasles reads his Conics as bearing the mark of what would become the foundation of Descartes’s analysis; namely that a single propriety between two magnitudes on a conic serves as a unifying notion on which the whole theory is built. See Chasles (1837a, 17–18).

These lectures were given a few years after the texts on the attraction of ellipsoids, and Chasles’s reflections on generality expressed therein display some subtle variations, but these are out of the scope of this paper.

This call for a renewal of the language of geometry can also be found in Poncelet’s well-known Traité des propriétés projectives (Poncelet 1822, 22).

This notion can be compared to Steiner’s “systematicity”. See for instance Lorenat (2016), in particular p. 429.

“La méthode d’exhaustion, qui reposait sur une idée mère tout à fait générale, n’ta point à la Géométrie son caractère d’étroitesse et de spécialité, parce que cette conception y manquant de moyens généraux d’application, devenait, dans chaque cas particulier, une question toute nouvelle, qui ne trouvait de ressources que dans les propriétés individuelles de la figure à laquelle on l’appliquait” (Chasles 1837a, 52).

“Aujourd’hui, chacun peut se présenter, prendre une vérité quelconque connue, et la soumettre aux divers principes généraux de transformation; il en retirera d’autres vérités, différentes ou plus générales; et celles-ci seront susceptibles de pareilles opérations; de sorte qu’on pourra multiplier, presque à l’infini, le nombre des vérités nouvelles déduites de la première. […] le génie n’est plus indispensable pour ajouter une pierre à l’édifice” (Chasles 1837a, 268–269).

“Cette influence utile de la Géométrie descriptive s’étendit naturellement aussi sur notre style et notre langage en mathématiques, qu’elle rendit plus aisés et plus lucides, en les affranchissant de cette complication de figures dont l’usage distrait de l’attention qu’on doit au fond des idées, et entrave l’imagination et la parole. La Géométrie descriptive, en un mot, fut propre à fortifier et à développer notre puissance de conception; à donner plus de netteté et de süreté à notre jugement; de précision et de clarté à notre langage” (Chasles 1837a, 190).

“Généraliser de plus en plus les propositions particulières, pour arriver de proche en proche à ce qu’il y a de plus général; ce qui sera toujours, en même temps, le plus simple, le plus naturel et le plus facile;

Ne point se contenter, dans la démonstration d’un théorème ou la solution d’un problème, d’un premier résultat, qui suffirait s’il s’agissait d’une recherche particulière, indépendante du système général d’une partie de la science; mais ne se satisfaire d’une démonstration ou d’une solution, que quand leur simplicité, ou leur déduction intuitive de quelque théorie connue, prouvera qu’on a rattaché la question à la véritable doctrine dont elle dépend naturellement.

Pour indiquer un moyen de reconnaître si la pratique de ces deux règles a conduit au but désiré, c’est-à-dire si l’on a rencontré les vraies routes de la vérité définitive, et pénétré jusqu’à son origine, nous croyons pouvoir dire que, dans chaque théorie, il doit toujours exister, et que l’on doit reconnaître, quelque vérité principale dont toutes les autres se déduisent aisément, comme simples transformations ou corollaires naturels; et que cette condition accomplie sera seule le cachet de la véritable perfection de la science” (Chasles 1837a, 115).

“Les principes les plus généraux, c’est-à-dire qui s’étendent sur le plus grand nombre de faits particuliers, doivent tre dégagés des diverses circonstances qui semblaient donner un caractère distinctif et différent à chacun de ces faits particuliers, considéré isolément, avant qu’on eüt découvert leur lien et leur origine commune: s’ils étaient compliqués de toutes ces circonstances ou propriétés particulières, ils en porteraient l’empreinte dans tous leurs corollaires, et ne donneraient lieu, généralement, qu’à des vérités excessivement embarrassées et compliquées elles-mëmes. Ces principes les plus généraux sont donc nécessairement, par leur nature, les plus simples” (Chasles 1837a, 116).

The classical definitions of these two terms in Ancient Greek geometry notwithstanding (Chasles 1837a, 5), as these are of little relevance to our case. Note that in Chasles (1852), however, an interesting link is drawn between the ancient use of these terms and their more recent acceptations. See the Discours inaugural, pp. 550–576.

See for instance the quote by Poinsot given in Chasles (1837a, 252).

The term “rational geometry” also appears sometimes in Chasles’s writings.

“La Géométrie de Descartes, […] se distingue encore de la Géométrie ancienne sous un rapport particulier, qui mérite d’être remarqué; c’est qu’elle établit, par une seule formule, des propriétés générales de familles entières de courbes; de sorte que l’on ne saurait découvrir par cette voie quelque propriété d’une courbe, qu’elle ne fasse aussitôt connaître des propriétés semblables ou analogues dans une infinité d’autres lignes” (Chasles 1837a, 95).

Let us remember that this very theory was first supposed to be part of an exposition dogmatique of modern geometry previously mentioned.

“Mac-Laurin sut tirer, de quelques propriétés des coniques, toutes les ressources suffisantes pour la solution de cette question, qui a toujours passé, auprès des plus célèbres analystes, pour l’une des plus difficiles” (Chasles 1837a, 163).

Chasles’s emphasis is striking in Chasles (1846, 633): “MacLaurin a formellement démontré son théorème”.

“Mémoire fort beau et très-profond, et qui serait plus riche encore en résultats intéressants, si M.Legendre avait donné la signification géométrique de plusieurs des nombreuses formules par lesquelles il lui faut passer, pour arriver à la conclusion du théorème en question” (Chasles 1837a, 165).

“Déjà, dans les plus savantes recherches physico-mathématiques, l’Analyse a dévoilé la présence de ces surfaces; mais le plus souvent on a regardé une si heureuse circonstance comme fortuite et secondaire, sans songer qu’au contraire elle pouvait se rattacher directement à la cause première du phénomène, et mëme ëtre prise pour l’origine réelle, et non pas accidentelle, de toutes les circonstances qu’il peut offrir” (Chasles 1837a, 251).

For more on the readership of this journal, see Masson (2014).

All references are made to this 1846 edition.

Chasles gives quotes by Legendre and Poisson (among others) to that effect, see for instance Chasles (1846, 640).

Note that a similar concern is expressed in the Aperçu, Ch. VI, p. 253: “Monge’s descriptive geometry is being taught. […] But the other methods we have talked about are still scattered in the Memoirs of the geometers who used them, Memoirs which may seem lengthy and painful to read, because of the very large amount of new results they include. This is, I believe, the real cause for the detachment to rational geometry, where one mistakenly perceives, and this mistake is to be deplored, a mere chaos of new propositions found by chance, with no connection between them, and no future for a noteworthy improvement of the science of extension”. Here, rational geometry can be roughly understood to refer to pure geometry.

Homotheties (a term introduced by Chasles himself) refer to figures which derive from one another by a homogeneous dilation. Here, the second ellipsoid is obtained by enlarging the first ellipsoid (and shifting its center from G to S), with a scale factor of \(\lambda\).

This sort of expression would disappear in his later works, where talks of homographic correspondences replace this cinematic viewpoint, in particular in the wake of Chasles (1852).

For more on Carnot, see Chemla (1998), in particular p. 172.

This quantity can be thought of as the power of point S with respect to a conic. One can find a similar result already in Apollonius’s Conics, III, 27. Chasles does not mention any particular source for this theorem.

See the footnote in Chasles (1846, 646) for the details of this transformation.

In particular, in Chasles (1852), correspondences are substituted to transformations, which elicited some bitter remarks by Poncelet.

Let us note here that they form an exemple of a triply orthogonal system of surfaces, which would go on to form the basis of important works by Gaston Darboux, whose doctoral thesis on this subject was supervised by Chasles himself in 1866.

While we can’t give the details here, the reader is referred to Chasles (1846, 655–663).

Giving the details of this construction is well without the scope of this paper. We hope, however, that the details given above will enable the curious reader to follow Chasles’s proof, which is to be found in Chasles (1846, 645–663).

This is the very same “intersecting chords theorem for conics” used at the very beginning of this proof.

While we do not tackle it in this paper, the computation of the intensity of this attraction is carried out in several different ways by Chasles across his memoirs, which also highlight different practices of computations, with various levels of geometrical interpretation involved. In Chasles (1837c), Chasles uses the Laplacian equation \(\varDelta V = 0\) (V denoting here the potential), and an integration method first devised in Lamé (1837). In other texts, he tries to limit the need for differential calculus.

As did Comte, in his Leçons de philosophie positive, in particular in his tenth lesson, where he states: “One can form a very clear idea of the geometrical science, conceived in its totality, if we assign as its general goal the reduction of comparisons of all sorts of extended volumes, surfaces, lines etc. to simple comparisons of straight lines.”

Do note, however, that this argument is limited to the case of Chasles’s specific conception of geometry, and wouldn’t describe the synthetic geometry of, say, Von Staudt.

Of course, this simplicity judgment by a nineteenth-century actor is wont to be at odds with our contemporary assessments. The fact that Chasles’s proof may seem more difficult to us than intricate calculations, whose technical basis is more likely to have been taught to us, should not distract us from the fact that our aim here is to understand how an actor’s epistemic values structure and guide his mathematical practice, and not to search for an hypothetical conceptual content of simplicity.

Poisson (1833, 499) mentions his early and continued interest in Ivory’s work.

“It will not be altogether unworthy of the notice of the Royal Society, if [my method contributes] to simplify a branch of physical astronomy of great difficulty, and which has so much engaged the attention of the most eminent mathematicians” (Ivory 1809, 347). These “eminent mathematicians”, according to what precedes this quotation, are mainly Legendre and Laplace. For more on the circulation of French Analysis in Great Britain (especially in context of astronomical studies), see Craik (2016).

This result has applications in the theory of billards, as well as in hyperbolic geometry, see for instance Stachel and Wallner (2004). Despite its name, most likely inherited after the publication of Dingeldey’s article on the geometry of conics in Klein’s and Meyer’s Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften, the theorem itself is not explicitly stated in Ivory’s memoir.

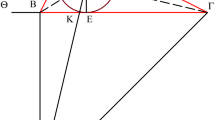

On a sheaf of confocal ellipsoids, correspondent points form confocal hyperboloids, which are orthogonal to the ellipsoids (see Fig. 5). These hyperboloids are among the orthogonal surfaces we described in the previous proof.

This is Chasles’s term for elements of volume.

“Ce théorème permet, quand on connaît les surfaces de niveau relatives à l’attraction d’un corps, de ramener le calcul de cette attraction à celui de l’attraction d’un corps infiniment mince. […] De sorte que ce problème, envisagé ainsi d’un point de vue général, se dépouille des grandes difficultés qu’il avait présentées quand on l’attaquait par des considérations restreintes et toutes spéciales à la forme particulière du corps. Ce cas paraît offrir un nouvel exemple des avantages de la généralisation en géométrie, pour simplifier les théories et y répandre une clarté intuitive” (Chasles 1839, 209–210).

“Mais, bien que la fonction considérée par Laplace n’ait pas cessé depuis de jouer un röle principal dans toutes les recherches de ce genre, c’est toujours sous un point de vue exclusivement analytique et dans l’équation différentielle du second ordre, qu’on l’a étudiée ; et l’on n’a pas songé à considérer certaines surfaces auxquelles donne lieu cette fonction ; surfaces analogues à celles qu’on appelle, dans la théorie des fluides, surfaces de niveau, et qu’on peut appeler aussi surfaces de niveau relatives à l’attraction du corps, parce que les attractions exercées par le corps sur les différents points de chacune de ces surfaces, sont dirigées suivant les normales” (Chasles 1842, 19).

Notice the similarity with the geometrical property at the center of the proof by correspondence above.

Although some restrictions ought to be put on Chasles’s statements for the theorems to satisfy modern criterias of exactness.

Although these ideas were not lost to everyone; see, for example, Benjamin Peirce, whose System of analytic mechanics develops a concept of “Chaslesian shells”.

References

Arnold, V. (1985). Some remarks on elliptic coordinates. Journal of Soviet Mathematics, 31(6), 3280–3289.

Bertrand, J. (1892). Éloge historique de Michel Chasles. Séances publiques annuelles de l’Académie des Sciences.

Borgnet, A. (1840). De l’attraction d’un ellipsoïde homogène sur un point matériel. PhD thesis, Faculté des sciences de Paris.

Carnot, L. (1806). Essai sur la théorie des transversales. Paris: Courcier.

Catalan, E. (1841). Attraction d’un ellipsoïde homogène sur un point extérieur ou sur un point intérieur. PhD thesis, Faculté des sciences de Paris.

Chasles, M. (1837a). Aperçu historique sur l’origine et le développement des méthodes en géométrie, particulièrement de celles qui se rapportent à la géométrie moderne, suivi d’un mémoire de géométrie sur deux principes généraux de la science: la dualité et l’homographie. Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

Chasles, M. (1837b). Mémoire sur l’attraction des ellipsoïdes. Journal de l’École polytechnique, 25e cahier, 244–265.

Chasles, M. (1837c). Mémoire sur l’attraction d’une couche ellipsoïdale infiniment mince. Journal de l’École polytechnique, 25e cahier, 266–316.

Chasles, M. (1838). Nouvelle solution du problème de l’attraction d’un ellipsoïde hétérogène sur un point extérieur. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, 6, 902–915.

Chasles, M. (1839). Énoncé de deux théorèmes généraux sur l’attraction des corps et la théorie de la chaleur. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, 8, 209–211.

Chasles, M. (1842). Théorème généraux sur l’attraction des corps. Additions à la Connaissance des Temps pour l'année 1845, 18–33.

Chasles, M. (1846). Mémoire sur l’attraction des ellipsoïdes. Solution synthétique pour le cas général d’un ellipsoïde hétérogne et d’un point extérieur. Mémoires des savants étrangers à l’Académie des sciences, 9, 629–715.

Chasles, M. (1852). Traité de géométrie supérieure. Paris: Bachelier.

Chasles, M. (1874). Considérations sur le caractère propre du principe de correspondance. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, 48, 577–585.

Chemla, K. (1998). Lazare carnot et la généralité en géométrie. Variations sur le théorème dit de menelaus. Revue d’histoire des mathématiques, 4(2), 163–190.

Chemla, K. (2016). The value of generality in Michel Chasles’s historiography of geometry. In K. Chemla, R. Chorlay, & D. Rabouin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of generality in mathematics and the sciences (pp. 47–89). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comte, A. (1830). Cours de philosophie positive, Vol. 1. Paris: Rouen Frères.

Craik, A. D. D. (2016). Mathematical analysis and physical astronomy in Great Britain and Ireland, 1790–1831: Some new light on the French connection. Revue d’histoire des mathématiques, 22(2), 223–294.

Croizat, B. (2016). Gaston Darboux: Naissance d’un mathématicien, génèse d’un professeur, chronique d’un rédacteur. PhD thesis, Université Lille 1.

Darboux, G. (1866). Sur les surfaces orthogonales. PhD thesis, Faculté des sciences de Paris.

Daston, L. (1995). The moral economy of science. Osiris, 10, 2–24.

Dawson, J. W. (2015). Why prove it again? Alternative proofs in mathematical practice. Cham: Birkhauser Verlag AG.

Grabiner, J. V. (1997). Was Newton’s calculus a dead end? The continental influence of Maclaurin’s Treatise of fluxions. The American Mathematical Monthly, 104(5), 393–410.

Gray, J. (2007). Worlds out of nothing. London: Springer.

Grattan Guinness, I. (1990). Convolutions in French mathematics, 1800–1840. Basel: Springer Basel AG.

Hamilton, W. R. (1853). Lectures on quaternions: Containing a systematic statement of a new mathematical method. Dublin: Hodges and Smith.

Hoppé, J.F. (1863). Attraction des ellipsoïdes homogènes. PhD thesis, Université de Strasbourg.

Ivory, J. (1809). On the attractions of homogeneous ellipsoids. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 99, 345–372.

Lamé, G. (1837). Mémoire sur les surfaces isothermes dans les corps solides homogènes en équilibre de température. Journal de mathématiques pures et appliquées 1ère série, 2, 147–183.

Legendre, A. M. (1788). Mémoire sur les intégrales doubles. In Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences. Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

Lorenat, J. (2016). Synthetic and analytic geometries in the publications of Jakob Steiner and Julius Plücker (1827–1829). Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 70(4), 413–462.

MacLaurin, C. (1742). A treatise of fluxions, Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Ruddimans.

Masson, F. (2014). Trois revues institutionnelles: Le Journal de l’École polytechnique, les Annales des Mines, les Annales des Ponts et Chaussées. Revue de Synthèse, 135(2–3), 255–269.

McLarty, C. (2003). The rising sea: Grothendieck on simplicity and generality. Unpublished manuscript.

Nabonnand, P. (2006). Contributions à l’histoire de la géométrie projective au 19e siècle, document présenté pour l’HDR.

Peslin, H. (1843). Attraction des Corps Quelconques, et en particulier des Ellipsoïdes etc. PhD thesis, Faculté des sciences de Paris.

Poisson, S. D. (1833). Mémoire sur l’attraction d’un ellipsoïde homogène. Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, 13, 497–545.

Poncelet, J. V. (1822). Traité des propriétés projectives. Paris: Bachelier.

Quetelet, A. (1872). Premier siècle de l’Académie Royale de Belgique. Bruxelles: Hayez.

Stachel, H., & Wallner, J. (2004). Ivory’s theorem in hyperbolic spaces. Siberian Mathematical Journal, 45(4), 785–794.

Wang, X. (2017). The teaching of analysis at the École polytechnique: 1795–1805. PhD thesis, Université Paris-Diderot.

Acknowledgements

I would like to warmly thank Karine Chemla and Ivahn Smadja, as well as the two anonymous reviewers, for their pertinent comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. I am also indebted to María de Paz and José Ferreirós for organizing the workshop at which this paper was first presented. I was supported by the Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin while writing the final version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Michel, N. The Values of Simplicity and Generality in Chasles’s Geometrical Theory of Attraction. J Gen Philos Sci 51, 115–146 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-019-09451-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-019-09451-z