Abstract

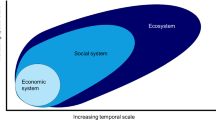

We present a new evolutionary political economy approach to the study of transition dynamics based on a co-evolutionary model of differential citizen contributions to competing ‘utopias’—market fundamentalism, socialism, and environmentalism. We model sustainability transitions as an outcome of ‘utopia competition’ in which environmentalism manages to coexist with the market, while socialism vanishes. Our simulation-based framework suggests that the individual economic contributions of citizens to the battle of ideas—both the distribution within a utopia, and the interaction between different utopias—are crucial but much overlooked micro-factors in explaining the dynamics of sustainability transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Citizens may not only devote their resources (time, effort, money, reputation, and so forth) to persuade others in the so-called Public Sphere (Habermas 1989). Citizens can also devote their resources to direct engagement in other promotional actions, such as becoming members of civil activist organizations, or founding new firms or organizations committed to these goals. In this sense, Dopfer’s (1991) conception of ideas as time-less and space-less entities with morphic power, comes to mind. Extending our proposal along this line of ideologies (or entire world-views and utopias) as “closure judgements” suggests a useful path for future research.

Specifically, we set a model in which several population dynamics systems are interwoven (coupled). Some technicalities and definitions regarding “coupled replicator equations”—although in an evolutionary game-theoretic context—can be seen in Sato and Crutchfield (2003).

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail?. New York: Crown Business.

Almudi, I., Fatas-Villafranca, F., Izquierdo, L. R., & Potts, J. (2015). The economics of utopia: A co-evolutionary model of ideas, citizens and civilization. Working Paper, RMIT, UZ & UBU.

Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Daily, G., Ehrlich, P., Heal, G., Levin, S., Maler, K., Schneider, S., & Walker, B. (2004). Are we consuming too much? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18, 147–172.

Barrett, S. (2003). Environment and statecraft. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barrett, S. (2007). Why cooperate? The incentives to supply global public goods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bergek, A., Jacobsson, S., Carlsson, B., Lindmark, S., & Rickne, A. (2008). Analysing the functional dynamics of technological innovation systems: A scheme of analysis. Research Policy, 37, 407–29.

Berkhout, F. (2006). Normative expectations in systems innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18, 299–311.

Boulding, K. (1978). Ecodynamics. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage.

Brekke, K. A., & Johansson-Stenman, O. (2008). The behavioral economics of climate change. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24, 280–297.

Costa, D., & Kahn, M. (2003). Civic engagement and community heterogeneity: An economist’s perspective. Perspectives on Politics, 1, 103–111.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302, 1907–1912.

Dopfer, K. (1991). Towards a theory of economic institutions: Synergy and path dependency. Journal of Economic Issues, 25, 535–550.

Dopfer, K., & Potts, J. (2008). General theory of economic evolution. London: Routledge.

Earl, P., & Potts, J. (2004). The market for preferences. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 28, 619–33.

Fatas-Villafranca, F., Saura, D., & Vazquez, F. J. (2011). A dynamic model of public opinion formation. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 13, 417–41.

Geels, F. (2002). Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Research Policy, 31, 1257–74.

Geels, F. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Research Policy, 33, 897–920.

Geels, F. (2010). Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Research Policy, 39, 495–510.

Goulder, L., & Pizer, W. (2008). Climate change, economics of. In S. Durlauf & L. Blume (Eds.), New Palgrave dictionary of economics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gowdy, J. (1994). Co-evolutionary economics. New York: Springer.

Gowdy, J. (2008). Behavioral economics and climate change policy. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68, 632–44.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Hodgson, G. (1999). Economics and Utopia: Why the learning economy is not the end of history. London: Routledge.

Hofbauer, J., & Sigmund, K. (1998). Evolutionary games and population dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joosten, R. (2006). Walras and Darwin: An odd couple. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 191, 561–573.

Kates, R. W., Clark, W. C., Corell, R., Hall, J. M., Jaeger, C. C., Lowe, I., McCarthy, J. J., Schellnhuber, H. J., Bolin, B., Dickson, N. M., Faucheux, S., Gallopin, G. C., Grübler, A., Huntley, B., Jäger, J., Jodha, N. S., Kasperson, R. E., Mabogunje, A., Matson, P., Mooney, H., Moore, B. III, O’Riordan, T., & Svedlin, U. (2001). Environment and development: Sustainability science. Science, 292, 641–42.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. London: Palgrave McMillan.

Leighton, W., & Lopez, E. (2012). Madmen, intellectuals and academic scribblers: The economic engine of political change. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Towards a research agenda on sustainability transitions. Introduction paper to special section on sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 41, 955–67.

Markey-Towler, B. (2016). Law of the jungle: Firm survival and price dynamics in evolutionary markets. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 26, 655–696.

Montgomery, S., & Chirot, D. (2015). The shape of the new. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nordhaus, W. (2015). Climate clubs: Overcoming free-riding in international climate policy. American Economic Review, 105, 1339–70.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. (1989). Constitution and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. Journal of Economic History, 49, 803–32.

Ortega-Egea, J. M., García-de-Frutos, N., & Antolín-López, R. (2014). Why do some people do “more” to mitigate climate change than others? Exploring heterogeneity in psycho-social associations. PLoS ONE, 9(9), e106645.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Page, B., & Shapiro, R. (1992). The rational public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pizer, W. (2002). Combining price and quantity controls to mitigate global climate change. Journal of Public Economics, 85, 409–34.

Sato, Y., & Crutchfield, J. (2003). Coupled replicator equations for the dynamics of learning in multiagent systems. Physical Review, 67, 015206 (R).

Sexton, S. (2011). Conspicuous conservation. http://works.bepress.com/sexton/11.

Stern, P., & Dietz, T. (1994). The value basis of environmental concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50, 65–80.

Van den Bergh, J., Truffer, B., & Kallis, G. (2011). Environmental innovation and societal transitions: Introduction and overview. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1, 1–23.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Australian Research Council (Grant No. FT120100509).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Almudi, I., Fatas-Villafranca, F. & Potts, J. Utopia competition: a new approach to the micro-foundations of sustainability transitions. J Bioecon 19, 165–185 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-016-9239-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-016-9239-2