Abstract

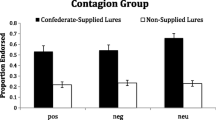

Previous studies have suggested that negative emotion can enhance memory accuracy. However, they were not conducted in the context of social interactions using the methodology of experimental economics. Based on the present study, we find that in such a context, individuals’ memory recall accuracy depends on the kindness of acts and who performed them, and negative emotion may lower memory accuracy. A victim of an unkind act is more likely to forget than someone who benefited from a kind act. This result supports the hypothesis that individuals may strategically manipulate their memory by forgetting an unpleasant experience. We also find that individuals who committed an unkind act tend to perceive it as less unkind as time moves on. They also tend to believe that a higher percentage of players have also committed the unkind act. Overall, the results support the hypothesis that individuals strategically manipulate their memory and beliefs to maintain self-esteem or feel less guilty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Fehr and Schmidt (2006) for an extensive review, especially experimental evidences, of social preference in the literature of economics.

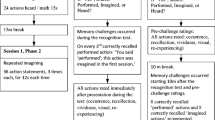

Subjects received an email inviting them to participate in the second stage of the experiment. They could click on a link (which directed them to an online questionnaire) in the email to start the second stage.

It appears that player As exhibit higher error rate of recalling player Bs’ choice across time, see Fig. 2(a). Identifying the exact mechanism on how memory losses across time can be an interesting topic for future research.

One may wonder if there is a relationship between memory recall and expectation. One possibility is that player A’s memory recall accuracy may be affected by his/her ex ante expectation on the strategy of player B. The idea is that one may be able to remember better if the realized choice is different from the expectation, in other words, surprise events are easier to remember. If this is true, it implies that memory recall does not only depend on the emotion state induced by the event but also on the players’ expectation. Hence, a negative emotion does not necessarily lead to better memory recall than a positive emotion. To test for this possibility, I compare the recall error rate of the group of player As who estimate the percentage of player Bs choosing B2 as lower than 50 percent opposed to those who estimate the percentage as at least 50 percent. In contrast to the prediction, it is found that, given the actual choice of B2, the former rather than the latter group had a higher proportion of subjects who recalled incorrectly, p value equals to 0.10.

Another possible mechanism is that when player A forgets, he/she may use his/her ex ante expectation on the strategy of player B when making a guess. In other words, if (in the first guess) the player expects B2 is more likely to be chosen, he/she will guess on B2 in the questionnaire. According to this mechanism, conditional on B2 being the actual choice and the fact there is a higher proportion of player As who think B2 will be more likely to be chosen, we should observe a higher error rate in recalling B1 than B2. However, the reverse is observed. In sum, this analysis adds to the evidence that remembering one was betrayed can be emotionally costly.

We found no significant difference on the accuracy of memory recall by player B on recalling the choice of player A, and on recalling his/her own choice, conditional on his/her own actual choice and the actual choice of player A.

I exclude the observations (n=2) that gave a positive rating for B2 (i.e., rating player B’s choice of B2 as kind). For the ease of understanding, I report the rating of unkindness in the scale of 10,9,…,0, which correspond to −10,−9,…,0.

I exclude the observations (n=3) that gave a negative rating for B1 (i.e., rating player B’s choice of B1 as unkind).

In the literature of social psychology, it has been argued that time has an impact on reciprocity. For example, in one study by Burger et al. (1997), it is found that the degree of positive reciprocity toward an act of kindness by others decreases with time. The authors suggest that social rules require reciprocating only within a reasonable period of time rather than mandating an open-ended obligation to return a favor.

References

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2002). Self-confidence and personal motivation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 871–915.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122–142.

Bower, G. H., & Forgas, J. P. (2001). Mood and social memory. In Handbook of affect and social cognition (p. 95–120).

Burger, J. M., Horita, M., Kinoshita, L., Roberts, K., & Vera, C. (1997). Effects on time on the norm of reciprocity. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19(1), 91–100.

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory: experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Compte, O., & Postlewaite, A. (2004). Confidence-enhanced performance. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1536–1557.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism—experimental evidence and new theories. In S. C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Greenwald, A. G. (1980). The totalitarian ego: Fabrication and revision of personal history. American Psychologist, 35(7), 603–618.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Kensinger, E. A., Garoff-Eaton, R. J., & Schacter, D. L. (2006). Memory for specific visual details can be enhanced by negative arousing content. Journal of Memory and Language, 54(1), 99–112.

Levine, L., & Bluck, S. (2004). Painting with broad strokes: happiness and the malleability of event memory. Cognition and Emotion, 18(4), 559–574.

Levine, L. J., & Pizarro, D. A. (2006). Emotional valence, discrete emotions, and memory. In B. Uttl, N. Ohta, & A. L. Siegenthaler (Eds.), Memory and emotion: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 37–58). Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Loftus, E. F. (1980). Memory. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Mitchell, T. R., Thompson, L., Peterson, E., & Cronk, R. (1997). Temporal adjustments in the evaluation of events: The “rosy view”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33(4), 421–448.

Morris, W. N. (1999). The mood system. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & E. Schwarts (Eds.), The foundations of hedonic psychology New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Rummel, J., Hepp, J., Klein, S. A., & Silberleitner, N. (2012). Affective state and event-based prospective memory. Cognition and Emotion, 26(2), 351–361.

Taylor, S. E., & Crocker, J. (1981). Schematic bases of social information processing. In E. T. Higgins, C. Herman, & M. Zanna (Eds.), Social cognition: The Ontario Symposium (pp. 89–134). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I thank Chew Soo Hong, Daniel Zizzo, Robert Sugden, Anthony Ziegelmeyer, and especially Toru Suzuki and Robert Wyer for helpful comments and discussions. I also thank the Max Planck Society for financial support.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K.K. Asymmetric memory recall of positive and negative events in social interactions. Exp Econ 16, 248–262 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9325-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9325-9