Abstract

A recently developed self-report questionnaire, the Negative Self Portrayal Scale (NSPS; Moscovitch and Huyder in Behav Ther 42:183–196. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.007, 2011) assesses concerns about appearing socially incompetent, physically unattractive, and/or visibly anxious to evaluative others. Initial validation studies of the NSPS yielded promising results but were conducted exclusively on samples of undergraduate students. Here, we aimed to replicate and extend those initial studies by examining the factor structure, construct validity, and treatment sensitivity of the NSPS in samples of community-based participants with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (SAD), a principal anxiety disorder diagnosis other than SAD, or no history of psychological problems. Results provided support for the construct validity of the NSPS within clinical samples and suggested that the types of concerns assessed by the NSPS and its subscales may be useful for predicting individual differences in emotional and behavioral symptoms of social anxiety (SA) and for conceptualizing change processes during cognitive behavioral therapy for SAD. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that while the hypothesized three-factor model fit significantly better than an alternative one-factor model, the fit indices associated with the three-factor model were below satisfactory cutoffs, thus tempering conclusions that the best fitting structure was found and highlighting the need for additional research. Implications of these findings are discussed vis-à-vis Moscovitch’s (Cogn Behav Pract 16:123–134. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.04.002, 2009) theoretical model of SA and the potential utility of the NSPS for both clinical research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The disorder-specific treatment manuals used for the present study consisted of evidence-based CBT interventions adapted from several published CBT manuals and the scientific literature. More information about the specific treatment manuals is available upon request from the second author.

For the purposes of examining the factor structure of the NSPS, sample size constraints prohibited us from conducting a multiple group CFA. Prior to conducting the CFA on the pooled data, preliminary tests revealed that NSPS scores were not significantly associated with any of the demographic variables which may have differed across the subgroups. For example, the zero-order correlation between participant age and NSPS total scores was nonsignificant, r = .10, p = .19. Univariate ANOVAs further demonstrated that neither marital status, F(5,163) = .97, p = .44, nor ethnicity, F(5,167) = 1.0, p = .42, were predictive of NSPS total scores.

Equivalent results were found when the two CFA models were compared using only clinical participants (i.e., excluding the healthy controls).

Given that CBT for SA is geared toward addressing the types of concerns most typical of SA (and that this is not the focus of treatment for CBT for other AC conditions), it is reasonable to expect the Time × Treatment Focus interaction to be in only one direction (and not the opposite direction). Therefore, a one-tailed test of significance was used.

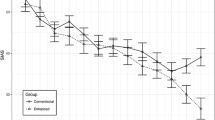

Examining each of the NSPS subscales separately in 2 (Time) × 2 (Treatment Focus) mixed ANOVAs revealed, interestingly, that there was a significant interaction for signs of anxiety, F(1,89) = 6.0, p = .01, η 2p = .07 (SA group: Pretreatment Mean = 22.5; SD = 7.8; Posttreatment Mean = 17.2; SD = 7.4; AC group: Pretreatment Mean = 15.9; SD = 6.0; Posttreatment Mean = 13.5; SD = 5.6), but not for social competence [F(1,89) = 1.7, p = .19, η 2p = .02], or for physical appearance [F(1,89) = 1.6, p = .20, η 2p = .02]. However, the pattern of differences between group means over time for each of these subscales was consistent with expectations, such that patients who received CBT for SAD reported greater changes in NSPS concerns about social competence (SA group: Pretreatment Mean = 35.5; SD = 11.1; Posttreatment Mean = 29.9; SD = 12.8; AC group: Pretreatment Mean = 22.3; SD = 9.6; Posttreatment Mean = 19.1; SD = 9.6) and physical appearance (SA group: Pretreatment Mean = 25.0; SD = 8.8; Posttreatment Mean = 21.8; SD = 8.9; AC group: Pretreatment Mean = 16.1; SD = 7.5; Posttreatment Mean = 14.4; SD = 7.7) from pre- to post-treatment than those who received CBT for other anxiety disorders.

For this reason, the items that comprise the physical appearance subscale of the NSPS were worded specifically to capture these more general SAD-relevant physical appearance concerns rather than the more focused concerns about particular physical body parts, attributes, or weight and shape, which might be more applicable to BDD and the eating disorders.

References

Alden, L. E., & Bieling, P. (1998). Interpersonal consequences of the pursuit of safety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 53–64. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00072-7.

Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2004). Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 857–882. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author.

Antony, M. M., Coons, M. J., McCabe, R. E., Ashbaugh, A., & Swinson, R. P. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory: Further evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1177–1185. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.013.

Antony, M. M., & Swinson, R. P. (2008). Shyness and social anxiety workbook: Proven, step-by-step techniques for overcoming your fear (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2008). AMOS 20 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory—II. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessment.

Buhlmann, U., Reese, H. E., Renaud, S., & Wilhelm, S. (2008). Clinical considerations for the treatment of body dysmorphic disorder with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Body Image, 5, 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.12.002.

Carelton, R. N., Mulvoque, M. K., Thibodeau, M. A., McCabe, R. E., Antony, M. M., & Asmundson, G. J. (2012). Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 268–479. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011.

Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. A., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007a). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 105–117. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014.

Carleton, R. N., Sharpe, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007b). Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty: Requisites of the fundamental fears? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2307–2316. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.006.

Chiupka, C. A., Moscovitch, D. A., & Bielak, T. (2012). In-vivo activation of anticipatory vs. post-event autobiographical images and memories in social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31, 783–809.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. Heimberg, M. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Conner, K. M., Davidson, J. R. T., Churchhill, E., Sherwood, A., Foa, E., & Weisler, R. H. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 379–386. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.4.379.

Cuming, S., Rapee, R. M., Kemp, N., Abbott, M. J., Peters, L., & Gaston, J. E. (2009). A self-report measure of subtle avoidance and safety behaviors relevant to social anxiety: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 879–883. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.002.

Dugas, M. J., & Robichaud, M. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: From science to practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

English, T., & John, O. P. (2013). Understanding the social effects of emotion regulation: The mediating role of authenticity for individual differences in suppression. Emotion, 13, 314–329. doi:10.1037/a0029847.

Fang, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2010). Relationship between social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1040–1048. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.001.

Fang, A., Sawyer, A. T., Aderka, I. M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder improves body dysmorphic concerns. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 684–691. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.005.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (2002). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Freeston, M., Rhéaume, J., Letarte, H., Dugas, M. J., & Ladouceur, R. (1994). Why do people worry? Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 791–802. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5.

Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36, 193–209. doi:10.1080/16506070701421313.

Hofmann, S. G., Heinrichs, N., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2004). The nature and expression of social phobia: Toward a new classification. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 769–797. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.004.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Kashdan, T. B., Weeks, J. W., & Savostyanova, A. A. (2011). Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: A self-regulatory framework and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 786–799. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.012.

Khawaja, N. G., & Yu, L. N. H. (2010). A comparison of the 27-item and 12-item intolerance of uncertainty scales. Clinical Psychologist, 14, 97–106. doi:10.1080/13284207.2010.502542.

Kollei, I., Schieber, K., de Zwaan, M., Svitak, M., & Martin, A. (2013). Body dysmorphic disorder and nonweight-related body image concerns in individuals with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46, 52–59. doi:10.1002/eat.22067.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

McManus, F., Sacadura, C., & Clark, D. M. (2008). Why social anxiety persists: An experimental investigation of the role of safety behaviours as a maintaining factor. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 39, 147–161. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.12.002.

Meng, X., Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 172–175. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.172.

Merrifield, C., Balk, D., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2013). Self-portrayal concerns mediate the relationship between recalled teasing and social anxiety in adults with anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 456–460. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.05.007.

Moscovitch, D. A. (2009). What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16, 123–134. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.04.002.

Moscovitch, D. A., Chiupka, C. A., & Gavric, D. L. (2013a). Within the mind’s eye: Negative mental imagery activates different emotion regulation strategies in high versus low socially anxious individuals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 426–432. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.05.002.

Moscovitch, D. A., Gavric, D. L., Merrifield, C., Bielak, T., & Moscovitch, M. (2011). Retrieval properties of negative vs. positive mental images and autobiographical memories in social anxiety: Outcomes with a new measure. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 505–517. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.009.

Moscovitch, D. A., & Huyder, V. (2011). The Negative Self-Portrayal Scale: Development, validation, and application to social anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 42, 183–196. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.007.

Moscovitch, D. A., Orr, E., Rowa, K., Reimer Gehring, S., & Antony, M. M. (2009). In the absence of rose-colored glasses: Ratings of self-attributes and their differential certainty and importance across multiple dimensions in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.007.

Moscovitch, D. A., Rowa, K., Paulitzki, J. R., Ierullo, M. D., Chiang, B., Antony, M. M., et al. (2013b). Self-portrayal concerns and their relation to safety behaviors and negative affect in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 476–486. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.002.

Moscovitch, D. A., Suvak, M. K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2010). Emotional response patterns during social threat in individuals with generalized social anxiety disorder and non-anxious controls. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 785–791. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.05.013.

Muthén, B., & Kaplan, D. (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38, 171–189.

Nevitt, J., & Hancock, G. R. (2001). Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 353–377.

Orr, E., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2014). Physical appearance anxiety impedes the therapeutic effects of video feedback in high socially anxious individuals. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42, 92–104.

Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., Gutierrez, P. M., Williams, J. E., & Bailey, J. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in nonclinical adolescent samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 83–102. doi:10.1002/jclp.20433.

Plasencia, M. L., Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2011). Differential effects of safety behaviour subtypes in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 665–675. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.005.

Rapee, R. M., Gaston, J. E., & Abbott, M. J. (2009). Testing the efficacy of theoretically derived improvements in the treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 317–327. doi:10.1037/a0014800.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 741–756. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3.

Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Hiding the self and social anxiety: The core extrusion schema measure. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33, 375–389. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9143-0.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Ruscio, A. M. (2010). The latent structure of social anxiety disorder: Consequences of shifting to a dimensional diagnosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 662–671. doi:10.1037/a0019341.

Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall.

Sideridis, G. D., Morgan, P. L., Botsas, G., Padeliadu, S., & Fuchs, D. (2006). Predicting LD on the basis of motivation, metacognition, and psychopathology: An ROC analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 215–229.

Taylor, C. T., & Alden, L. E. (2011). To see ourselves as others see us: An experimental integration of the intra and interpersonal consequences of self-protection in social anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 129–141. doi:10.1037/a0022127.

Van Ginkel, J. R., & Kroonenberg, P. M. (2014). Analysis of variance of multiply imputed data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 49, 78–91.

Weeks, J. W., Rodebaugh, T. L., Heimberg, R. G., Norton, P. J., & Jakatdar, T. A. (2009). “To avoid evaluation, withdraw”: Fears of evaluation and depressive cognitions lead to social anxiety and submissive withdrawal. Cognitive Research and Therapy, 33, 375–389. doi:10.1007/s10608-008-9203-0.

Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with non-normal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications (pp. 56–75). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We are grateful to Lisa Young, Maria Ierullo, and Brenda Chiang for collecting and compiling data, and to staff and patients at the Anxiety Treatment and Research Centre, whose cooperation and help were invaluable.

Conflict of Interest

David A. Moscovitch, Karen Rowa, Jeffrey R. Paulitzki, Martin M. Antony, and Randi E. McCabe declare that there have no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (national and institutional). Informed consent was obtained from all individual subjects participating in the study. If any identifying information is contained in the paper the following statement is also necessary. Additional informed consent was obtained from any subjects for whom identifying information appears in this paper.

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Negative Self-Portrayal Scale (NSPS)

Appendix: Negative Self-Portrayal Scale (NSPS)

According to the scale provided below, please write the number in the blank space beside each item to indicate the degree to which you are concerned about the following aspects of yourself when you are in anxiety

-

provoking

social situations (e.g., talking to someone who is a stranger; giving a speech in front of an audience; answering a question in class; etc.).

NSPS social competence subscale score = sum of items 3, 10, 12, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24; NSPS signs of anxiety subscale score = sum of items 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 15, 16, 25; NSPS physical appearance subscale score = sum of items 2, 5, 9, 11, 13, 22, 26, 27; NSPS total score = sum of all items.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moscovitch, D.A., Rowa, K., Paulitzki, J.R. et al. What If I Appear Boring, Anxious, or Unattractive? Validation and Treatment Sensitivity of the Negative Self Portrayal Scale in Clinical Samples. Cogn Ther Res 39, 178–192 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9645-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9645-5