Abstract

This paper explores the extent to which human capital improves the economic policy competence of US presidents. Several recent studies have used international data to test similar hypotheses. However, international studies suffer from a variety of comparability issues, not all of which can be avoided through fixed effects and error correction. The US results developed in this paper suggest that both career paths and education have significant effects on a president’s economic policy judgment, particularly in the period after the Civil War. However, the paper also suggests that more than good economic management skills are required to win national elections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A “Yellow Dog Democrat” is a person who would vote for a yellow dog (listed as a Democratic candidate), rather than a Republican candidate.

An early version of this paper was presented at the 2008 meetings of the Public Choice Society, where several useful comments were received. Subsequent versions of the paper have been posted on Social Science Research Network website since 2009.

This slogan was used by the Republican Party during Hoover’s 1928 campaign for office along with “vote for prosperity.”

Even in this case, presidential competence may influence policy choices at the margin. In their empirical estimations, Alesina and Rosenthal include the “components of competence” in the error term, because these components cannot be observed separately by the voters. The variance/covariance structure is used to examine whether “a change in party control of the White House makes a difference in aggregate economic growth in the year following the election.” This model of partisan administrative policy effectiveness is rejected by their analysis (Alesina and Rosenthal 1995: 216).

See Bordo and Rockoff (1996) for an overview of modifications to the Gold Standard during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of the effects that such policies had on international capital flows. See Cleveland and Powell (1909) for a thorough overview of state and national subsidies to US railroads.

A second reason to exclude the post 2000 observations is an apparent data entry error in the Mitchell series. Mitchell (2003), suggests that the average growth rate of GNP person during George H. W. Bush’s term was as high as 9.5 %. In contrast, the averaged growth rate of GDP per capita was only 0.7 %; hence, it is obviously a typographical error in Mitchell (2003). (If we include the entry for George H. W. Bush, the correlation between the Mitchell and Maddison per capita GDP series decreases to 0.8707.)

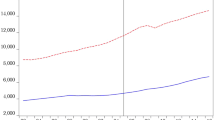

A regression between a president’s average growth rate of real per capita GNP on the previous president’s average in the 1870–2009 period yields: dYt = 0.02747 − 0.059dYt−1 with a t-statistic of 4.89 for the constant and of −3.23 for the coefficient. The coefficient should have been zero (statistically) if the dY series were stationary. The R2 for this regression is 0.31 and the DW is 2.14. Because it is unlikely that a “competent” president is always followed by an incompetent one, the most likely explanation is that business cycles occur for exogenous reasons but around a classical long-run steady-state growth path. Note that without shocks, the fact that the coefficient is less than one implies that, in the long run, the series is asymptotically stable (stationary) and would converge to the constant term, 0.02747, which can be interpreted as the long-run equilibrium growth rate of classical models (here, 2.7 %/year).

Military governors included Andrew Jackson and Andrew Johnson.

Martin van Buren.

After 1870, observations share the score of 0 on secretary of state, so we omit this variable from the estimates in Table 4.

When we distinguish between “Yrs House” and “Yrs Senate” and re-run years 4, we observe that both variables have positive but insignificant coefficients. The t statistic equals to 1.31 for “Yrs House,” and 0.76 for “Yrs Senate.”

Among the many pooling problems are assumptions that implicitly require institutions to be stable in the period of interest. Otherwise, country-fixed effects will not capture all relevant institutional differences. Political and economic institutions, however, changed at different rates during the 50 year period after 1875. Moreover, some of those changes may reflect the same leadership characteristics focused on in the international studies focusing on economic growth and political success (Hayo and Voigt 2013).

References

Alesina, A., & Rosenthal, H. (1995). Partisan politics, divided government, and the economy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Berger, M. M., Munger, M. C., & Potthoff, R. F. (2000). The downsian model predicts divergence. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 12, 228–240.

Besley, T. (2006). Principled agents? The political economy of good government. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Besley, T., Montalvo, J., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2011). Do educated leaders matter? Economic Journal, 121, 205–227.

Besley, T., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2011). Do democracies select more educated leaders? American Political Science Review, 105, 552–556.

Bordo, M. D., & Rockoff, H. (1996). The gold standard as a ‘good housekeeping’ seal of approval. Journal of Economic History, 56, 389–428.

Checchi, D. (2006). The economics of education: Human capital, family background, and inequality. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cleveland, F. A., & Powell, F. W. (1909). Railroad promotion and capitalization in the United States. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Congleton, R. D. (2007). Informational limits to democratic public policy: The jury theorem, yardstick competition, and ignorance. Public Choice, 132, 333–352.

Glass, D. P. (1985). Evaluating presidential candidates: Who focuses on their personal attributes? The Public Opinion Quarterly, 49, 517–534.

Groseclose, T. (2001). A model of candidate location when one candidate has a valence advantage. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 862–886.

Hayo, B., & Voigt, S. (2013). Endogenous constitutions: Politics and politicians matter, economic outcomes don’t. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 88, 47–61.

Hibbs, D. A. (1989). The American political economy: Macroeconomics and electoral politics in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lowi, T., Ginsberg, B., & Shepsle, K. A. (2002). American government: Power and purpose (7th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

MacRae, C. D. (1977). A political model of the business cycle. Journal of Political Economy, 85, 239–263.

Maddison, A. (2001). Development centre studies, The world economy: A millennial perspective. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Mitchell, B. R. (Ed.) (2003). International historical statistics (pp. 1750–2000). New York, NY: Palgrave.

Mondak, J. J. (1995). Competence, integrity, and the electoral success of congressional incumbents. Journal of Politics, 57, 1043–1069.

Nordaus, W. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 169–190.

Peffley, M. (1989). Presidential image and economic performance: A dynamic analysis. Political Behavior, 11, 309–333.

Ridings, W. J., Jr., & McIver, S. B. (1997). Rating the presidents: A ranking of U.S. leaders, from the great and honorable to the dishonest and incompetent. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Presidential style: Personality, biography, and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 607–619.

Simonton, D. K. (1995). Personality and intellectual predictors of leadership. In D. H. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence (pp. 739–757). New York, NY: Plenum.

Simonton, D. K. (2006). Presidential IQ, openness, intellectual brilliance, and leadership: estimates and correlations for 42 U.S. chief executives. Political Psychology, 27, 511–526.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Congleton, R.D., Zhang, Y. Is it all about competence? The human capital of U.S. presidents and economic performance. Const Polit Econ 24, 108–124 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-013-9138-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-013-9138-7